Какой пульс считается нормальным для человека того или иного возраста: сводная таблица значений по годам

23 января 2019179840 тыс.

Когда мы говорим «сердце стучит» или «бьется», мы тем самым характеризуем такое привычное для нас понятие, как пульс человека. То, что он реагирует на внутренние состояния или внешние воздействия – это норма. Пульс учащается от положительных эмоций и во время стрессовых ситуаций, при физических нагрузках и при заболеваниях.

Что бы ни стояло за частотой пульса, – это важнейший биологический маркер человеческого самочувствия. Но чтобы уметь «расшифровывать» сигналы, подаваемые сердцем в виде толчков и биений, нужно знать, какой пульс считается нормальным.

Что такое артериальный пульс: характеристика, свойства

Большинство медицинских терминов уходят корнями в латынь, так что, если задаваться вопросом, что такое пульс, стоит обратиться к переводу.

Дословно «пульс» означает толчок или удар, то есть мы даем верную характеристику пульса, говоря «стучит» или «бьется». А происходят эти удары вследствие сокращений сердца, приводящих к колебательным движениям артериальных стенок. Они возникают в ответ на прохождение по сосудистым стенкам пульсовой волны. Как она образуется?

- При сокращении миокарда кровь выбрасывается из сердечной камеры в артериальное русло, артерия в этот момент расширяется, давление в ней повышается. Этот период сердечного цикла называется систолой.

- Затем сердце расслабляется и «вбирает» в себя новую порцию крови (это момент диастолы), а давление в артерии падает. Все это происходит очень быстро – описание процесса артериального пульса занимает больше времени, чем его течение в действительности.

Чем больше объем выталкиваемой крови, тем лучше кровоснабжение органов, поэтому нормальный пульс – это та величина, при которой кровь (вместе с кислородом и питательными веществами) поступает в органы в необходимом объеме.

О состоянии человека при обследовании можно судить по нескольким свойствам пульса:

- частоте (количеству толчков в минуту);

- ритмичности (равенстве интервалов между ударами, если они не одинаковы, значит, сердцебиение аритмичное);

- скорости (падения и повышения давления в артерии, патологической считается ускоренная или замедленная динамика);

- напряжению (силе, требуемой для прекращения пульсации, пример напряженного сердцебиения – пульсовые волны при гипертонической болезни);

- наполнению (величины, сложенной частично из напряжения и высоты пульсовой волны и зависящей от объема крови в систоле).

Наибольшее влияние на пульсовое наполнение оказывает сила сжатий левого желудочка. Графическое изображение измерения пульсовой волны называется сфимографией.

Таблица нормального пульса человека по годам и возрастам представлена в нижнем разделе статьи.

Как измерить правильно?

Пульсирующий сосуд для измерения частоты пульса на человеческом теле можно прощупать в разных зонах:

- с внутренней стороны запястья, под большим пальцем (лучевая артерия);

- в зоне висков (височная артерия);

- на подколенном сгибе (подколенная);

- на сгибе в месте соединения таза и нижней конечности (бедренная);

- с внутренней стороны на локтевом сгибе (плечевая);

- на шее под правой стороной челюсти (сонная).

Самым популярным и удобным остается измерение ЧСС на лучевой артерии, этот сосуд расположен близко к кожному покрову. Для измерения необходимо найти пульсирующую «жилку» и плотно приложить к ней три пальца. Используя часы с секундной стрелкой, отсчитать количество биений за 1 минуту.

Сколько ударов в минуту должно быть в норме?

В понятие нормальный пульс вкладывают оптимальное количество биений сердца в минуту. Но этот параметр не является константой, то есть постоянной, поскольку зависит от возраста, сферы деятельности и даже половой принадлежности человека.

У здорового человека

Результаты измерения ЧСС во время обследования пациента всегда сравнивают с тем, сколько ударов в минуту должен быть пульс у здорового человека. Эта величина приближена к 60-80 биениям в минуту в спокойном состоянии. Но при определенных условиях допускаются отклонения от этой нормы сердечного пульса до 10 единиц в обе стороны. К примеру, считается, что ЧСС у женщин всегда на 8-9 ударов чаще, чем у мужчин. А у спортсменов-профессионалов сердце вообще работает в «эргономичном режиме».

Это значит, что оптимальным может считаться сердцебиение с частотой 50 ударов в минуту или 90 ударов. Более серьезные отклонения от нормы пульса здорового человека коррелируют с возрастом человека.

У взрослого

Ориентиром нормального пульса человека взрослого служат все те же 60-80 ударов в минуту. Такой пульс человека – норма для состояния покоя, если взрослый не страдает сердечно-сосудистыми и другими заболеваниями, оказывающими влияние на ЧСС. У взрослых людей частота сердцебиения повышается при неблагоприятных погодных условиях, при физических нагрузках, при эмоциональном всплеске. Для возвращения пульса человека в норму по возрасту бывает достаточно 10-минутного отдыха, это нормальная физиологическая реакция. Если же после отдыха возвращения ЧСС в норму не происходит, есть основания обратиться к врачу.

У мужчин

Если мужчина занимается интенсивными спортивными тренировками, то для него в состоянии покоя даже 50 ударов в минуту – пульс нормальный. У человека тренированного организм приспосабливается к нагрузкам, сердечная мышца укрупняется, благодаря чему увеличивается объем сердечного выброса. Поэтому сердцу не приходится совершать множественные сокращения, чтобы обеспечить нормальный кровоток – оно работает медленно, но качественно.

У мужчин, занятых умственным трудом может отмечаться брадикардия (ЧСС меньше 60 ударов в минуту), но ее сложно назвать физиологической, поскольку даже незначительные нагрузки у таких мужчин могут вызывать противоположное состояние – тахикардию (ЧСС выше 90 биений в минуту). Это негативно сказывается на работе сердца и может привести к инфаркту и другим серьезным последствиям.

Для приведения пульса в норму по возрастам (60-70 биений в минуту) мужчинам рекомендуется сбалансировать питание, режим и физические нагрузки.

У женщин

Норма пульса у женщин – 70-90 ударов в состоянии покоя, но на его показатели влияют многие факторы:

- заболевания внутренних органов;

- гормональный фон;

- возраст женщины и другие.

Заметное превышение нормы ЧСС наблюдается у женщин в период менопаузы. В это время могут отмечаться частые эпизоды тахикардии, перемежающиеся с другими аритмическими проявлениями и перепадами артериального давления. Многие женщины нередко «подсаживаются» в этом возрасте на седативные препараты, что не всегда оправдано и не слишком полезно. Самым правильным решением, когда в состоянии покоя пульс отклоняется от нормы, является посещение врача и подбор поддерживающей терапии.

У беременных

Изменение ЧСС у женщин в период вынашивания ребенка в большинстве случаев носит физиологический характер и не требует применения корректирующей терапии. Но чтобы убедиться в физиологичности состояния, необходимо знать, какой пульс нормальный для беременной.

Не забывая о том, что для женщины частота пульса 60-90 – норма, добавим, что при наступлении беременности ЧСС начинает постепенно учащаться. Для первого триместра характерно увеличение ЧСС в среднем на 10 ударов, а к третьему триместру – до 15 «лишних» толчков. Разумеется, эти толчки не лишние, они необходимы для перекачки увеличенного в 1,5 раза объема циркулирующей крови в кровеносной системы беременной. Сколько должен быть пульс у женщины в положении, зависит от того, какой была норма сердцебиения до наступления беременности – оно может быть и 75, и 115 ударов минуту. У беременных в III триместре норма пульса часто нарушается из-за лежания в горизонтальном положении, из-за чего им рекомендуют спать полулежа или на боку.

У детей

Самая высокая норма пульса у человека по возрастам – в младенческом возрасте. Для новорожденных пульс 140 в минуту – норма, но к 12-му месяцу эта величина постепенно снижается, достигая 110 – 130 биений. Учащенное сердцебиение в первые годы жизни объясняется интенсивным ростом и развитием детского организма, требующим усиленного обмена веществ.

Дальнейшее урежение ЧСС происходит не столь активно, и показатель 100 ударов в минуту достигается к 6-летнему возрасту.

Только в юношеском возрасте – 16-18 лет – ЧСС, наконец, достигает нормального пульса взрослого человека в минуту, снижаясь до показателей 65-85 толчков в минуту.

Какой пульс считается нормальным?

На частоту сердцебиения влияют не только заболевания, но и временные внешние воздействия. Как правило, временное учащение ЧСС удается восстановить после кратковременного отдыха и устранения провоцирующих факторов. А каким должен быть нормальный пульс для человека в различных состояниях?

В состоянии покоя

Та величина, которая считается нормой пульса для взрослого человека, на самом деле является частотой сердцебиений в покое.

То есть, говоря о норме здорового сердцебиения, всегда имеем в виду величину, измеряемую в покое. Для взрослого человека эта норма составляет 60-80 биений в минуту, но при определенных условиях норма может быть и 50 ударов (у тренированных людей) и 90 (у женщин и молодых людей).

При физических нагрузках

Чтобы рассчитать, какой у человека нормальный пульс при умеренных физических нагрузках, специалисты предлагают следующие математические операции:

- Величина максимального пульса рассчитывается как разница числа 220 и количества полных лет человека. (Например, для 20-летних эта величина составит: 220-20=200).

- Величина минимального пульса (50% от максимального): 200:100х50 = 100 ударов.

- Норма пульса при умеренных нагрузках (70% от максимального): 200:100х70 = 140 биений в минуту.

Физические нагрузки могут иметь различную интенсивность – умеренную и высокую, в зависимости от чего и норма пульса у человека, получающего эти нагрузки, будет различной.

Запомним – для умеренных физических нагрузок норма пульса колеблется от 50 до 70% от максимальной величины, исчисляемой как разница между числом 220 и полным количеством лет человека.

При беге

При высоких физических нагрузках, примером которых является бег (а также плавание на скорость, аэробика и т.п.), норма пульса рассчитывается по схожей схеме. Чтобы узнать, какая частота пульса человека считается нормальной во время бега, пользуются следующими формулами:

- Узнают разницу между числом 220 и возрастом человека, то есть максимальный пульс: 220-30 = 190 (для 30-летних).

- Определяют 70% от максимума: 190:100х70 = 133.

- Определяют 85% от максимума: 190:100х85 = 162 удара.

Норма пульса при беге колеблется от 70 до 85% от максимальной величины, являющейся разницей между 220 и возрастом человека.

Для сжигания жира

Формула вычисления максимального пульса пригодится и при расчете нормы ЧСС для сжигания жира.

Большинство фитнес-тренеров используют для расчетов метод финского физиолога и военного врача М.Карвонена, разработавшего метод определения границ пульса для физических тренировок. Согласно этому методу целевой зоной или ЗСЖ (зоной сжигания жира) является ЧСС в пределах от 50 до 80% от максимального пульса.

При подсчете максимального пульса сердца норма по возрастам не учитывается, но сам возраст в расчет берется. Для примера возьмем возраст 40 лет и рассчитаем норму пульса для ЗСЖ:

- 220 – 40 = 180.

- 180х0,5 = 90 (50% от максимума).

- 180х0,8 = 144 (80% от максимума).

- ЗСЖ колеблется от 90 до 144 ударов в минуту.

Почему получается такой разброс в цифрах? Дело в том, что норма частоты сердцебиений для тренировок должна подбираться индивидуально, с учетом тренированности, самочувствия и других особенностей организма. Поэтому перед началом тренировок (да и в их процессе) необходимо медицинское обследование.

После еды

Гастрокардиальный синдром – ощутимое повышение частоты сердцебиений после еды – может наблюдаться при различных болезнях ЖКТ, сердечно-сосудистой, эндокринной системы. О патологическом состоянии говорит сердцебиение, значительно превышающее норму. Неужели есть норма повышения ЧСС во время еды?

Строго говоря, небольшое учащение ЧСС во время или спустя 10-15 минут после еды является физиологичным состоянием. Поступившая в желудок пища давит на диафрагму, что заставляет человека глубже и чаще дышать – отсюда и усиление ЧСС. Особенно часто происходит превышение нормы пульса при переедании.

Но даже если пищи съедено немного, а сердце все равно начинает стучать быстрее, это не всегда признак патологии. Просто для переваривания пищи требуется усиление метаболизма, а для этого – и небольшое повышение ЧСС.

Норма пульса после еды примерно равна нормальному показателю при умеренных физических нагрузках.

Рассчитывать его мы уже научились, остается только сравнить собственный пульс после еды с нормой, вычисленной по формуле.

Таблица частоты сердечных сокращений по возрастам

Для сравнения собственных измерений с оптимумом полезно иметь под рукой таблицу нормы пульса по возрастам. В ней приведены минимально и максимально допустимые значения ЧСС. Если ваше сердцебиение меньше минимального показателя нормы, можно заподозрить брадикардию, если больше максимального – возможна тахикардия. Но определить это может только врач.

Таблица. Нормы пульса человека по возрасту.

| Возрастная категория | Минимальное значение нормы (ударов в минуту) | Максимальное значение нормы (ударов в минуту) | В среднем (ударов в минуту) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Первый месяц жизни | 110 | 170 | 140 |

| Первый год жизни | 100 | 160 | 130 |

| До 2 лет | 95 | 155 | 125 |

| 2-6 | 85 | 125 | 105 |

| 6-8 | 75 | 120 | 97 |

| 8-10 | 70 | 110 | 90 |

| 10-12 | 60 | 100 | 80 |

| 12-15 | 60 | 95 | 75 |

| До 18 | 60 | 93 | 75 |

| 18-40 | 60 | 90 | 75 |

| 40-60 | 60 | 90-100 (у женщин повышен) | 75-80 |

| старше 60 | 60 | 90 | 70 |

Данные приведены для людей без особых патологий и замеров в состоянии полного покоя, то есть сразу после пробуждения или после 10-минутного отдыха лежа. Женщинам после 45-ти стоит обратить внимание на несколько завышенную норму ЧСС, что связано с гормональной перестройкой в период климакса.

Полезное видео

Из следующего видео можно узнать дополнительную информацию о норме пульса человека:

Заключение

- Частота сердцебиений представляет собой важный физиологический показатель человеческого здоровья.

- Норма пульса разнится в зависимости от возраста, пола, тренированности и других физических особенностей организма человека.

- Временные колебания ЧСС на 10-15 единиц могут носить физиологический характер и не всегда требуют медикаментозного вмешательства.

- Если ЧСС человека превышает норму по возрасту на значительное количество ударов в минуту, необходимо обратиться к врачу и выяснить причину отклонения.

Как измерить свой пульс, и зачем это делать

Частота сердечных сокращений (ЧСС), которую нередко называют «пульсом», показывает, сколько раз в минуту бьется сердце. Этот показатель различается в зависимости от того, что делает человек. Во время сна частота сердечных сокращений значительно ниже, чем во время бега.

Несмотря на то, что ЧСС и пульс выражаются одинаковыми цифрами, техническая разница между этими двумя показателями есть.

ЧСС – это показатель того, столько ударов сердца происходит за определённый промежуток времени, обычно за минуту.

Пульс – это индикатор движения крови по артериям. Приложив палец к крупной артерии, можно почувствовать, как сердце перекачивает кровь.

Врачи используют показатель частоты сердечных сокращений для контроля здоровья человека. А люди, занимающиеся спортом, – чтобы определить эффективность тренировок.

Что такое нормальная частота сердечных сокращений?

Для человека старше 18 лет нормальная ЧСС в состоянии покоя составляет от 60 до 100 ударов в минуту. Чем более натренирована сердечно-сосудистая система – тем меньше требуется сердечных сокращений, чтобы организм получил необходимые питательные вещества и кислород с кровью.

У профессиональных спортсменов ЧСС в покое может быть около 40 ударов в минуту.

Нормальным пульсом в состоянии покоя считается:

– Для новорожденного – 120-160 ударов в минуту,

– Для малыша от 1 месяца до года – 80-140 ударов в минуту,

– Для ребёнка в возрасте от 2 до 6 лет – 75-120 ударов в минуту,

– Для ребенка в возрасте от 7 до 12 лет – 75-110 ударов в минуту,

– Для людей старше 18 лет – 60-100 ударов в минуту,

– Для взрослых спортсменов – 40-60 ударов в минуту.

Как проверить свою ЧСС?

На запястье (на лучевой артерии). Поверните руку ладонью вверх. Положите два пальца на запястье с наружной стороны руки. Почувствуйте толчки крови под подушечками пальцев. Возьмите часы или секундомер и посчитайте количество толчков в течение минуты или 30 секунд, умножив этот показатель на два.

На шее (на сонной артерии). Поместите указательный и безымянный пальцы руки на шее, рядом с трахеей. Посчитайте количество ударов в минуту.

Кроме того, пульс можно проверить и на других крупных сосудах:

– в районе бицепса или локтевого сгиба,

– на голове рядом с ухом,

– посредине подъема стопы,

– на виске,

– на краях нижней челюсти,

– в паху.

Также вы можете воспользоваться пульсометром. Пульсометры существуют в качестве самостоятельных приборов, но могут входить в конструкции часов и даже мобильных телефонов.

Что влияет на ЧСС?

На частоту сердечных сокращений влияют несколько факторов:

– тренированность,

– температура окружающей среды,

– положение тела (стоя, сидя, лежа),

– эмоциональное состояние: волнение, гнев, страх, тревога приводят к повышению ЧСС,

– наличие лишнего веса,

– прием лекарств, алкоголя или курение.

Если у нетренированного человека сердце бьется слишком медленно – менее 60 ударов в минуту – это называется брадикардия.

Если в состоянии покоя у взрослого нетренированного человека сердце бьётся быстрее 100 ударов в минуту – это называется тахикардия.

Если вы наблюдаете у себя подобные симптомы, которые сопровождаются головокружением, одышкой или обмороком – срочно обратитесь к врачу.

Что такое максимальная частота сердечных сокращений?

Этот показатель говорит о том, сколько ударов в минуту ваше сердце может сделать максимально – при физической нагрузке. Во время занятий спортом он позволяет оценить, насколько интенсивна нагрузка, которую вы получаете.

Обычно максимальная ЧСС считается по математической формуле, в которой учитывается возраст человека.

Для взрослых мужчин МЧСС = 220 – возраст. То есть у 25-летнего мужчины максимальная частота сердечных сокращений будет составлять 195 ударов в минуту.

Для взрослых женщин расчёт такой же, но иногда применяется формула с поправкой: МЧСС = 226 – возраст. То есть для 25-летней женщины этот показатель будет составлять 201 удар в минуту.

Частота́ серде́чных сокраще́ний (ЧСС, ткж. частота ритма) — физическая величина, получаемая в результате измерения числа сердечных систол в единицу времени. Традиционно измеряется в единицах: «число ударов в минуту» (уд/мин), — хотя в соответствии с СИ следовало бы измерять в герцах.

ЧСС используется в медицинской и спортивной практике как физиологический показатель нормального ритма сердцебиения и является важным признаком для первичного различения нормального ритма сердца и разнообразных нарушений ритма сердца (аритмий)[B: 1][B: 2]. Определяется также максимально допустимая частота сердечных сокращений.

Методы измерения[править | править код]

Методы измерения регистрации ЧСС в основном совпадают с методами регистрации вариабельности сердечного ритма.

Количественную оценку ЧСС обычно получают при помощи измерения количества пульсовых ударов в минуту или по количеству желудочковых комплексов на электрокардиограмме.

В соответствии с ГОСТом[D: 1], «регистрирующий прибор для измерения зависимости частоты сердечных сокращений от времени» следует называть ритмокардиограф и такие записи следует называть ритмокардиограммами (недопустимыми считаются названия «тахокардиограф», «кардиотахограф», «кардиоциклограф»).

Конвенциональные соглашения[править | править код]

Нормальный регулярный синусовый ритм[править | править код]

Правильным, или регулярным, синусовым ритмом (англ.) (рус. принято называть ритм сердца, который в пределах наблюдения задаётся только активностью синусового узла (СУ). Правильный ритм синусового узла принято называть нормальным синусовым ритмом, если он попадает в диапазон 60—90 ударов в минуту[B: 3][B: 4]. Небольшие колебания значений ЧСС, менее 0,1 секунды, считаются нормальной (физиологической) синусовой аритмией, связанной с естественной вариабельностью ритма сердца; их не считают нарушением ритма сердца.[1]

При помощи фармакологического воздействия (например, при сочетанном использовании обзидана и атропина) во время проведения функциональных тестов оказывается возможным измерить истинный ритм синусового узла (ИРСУ), то есть ЧСС при собственном автоматизме синусового узла без регуляторных воздействия на него.[2]

«Собственная» ЧСС у здорового человека при измерении ИРСУ оказывается обычно выше той, которая существует в условиях покоя; считается, что это свидетельствует о существенном преобладании парасимпатических влияний на синусовый узел[A: 1]; ИРСУ равен приблизительно 80-100 импульсов в минуту[B: 5][3]. И наоборот, высокая ЧСС в покое может отражать повышенную активность симпатической, на сниженную активность парасимпатической нервной системы, или на сочетание этих двух состояний. Мгновенные значения ЧСС не могут в полной мере отражать изменения симпато-вагусного взаимодействия, так как подвержены большому числу иных влияний, и потому для изучения автономной активности используется вариабельность сердечного ритма[A: 1].

ЧСС зависит от возраста, пола и внешних факторов. У новорождённых она составляет от 120 до 140 ударов в минуту и с возрастом снижается. У мужчин частота сокращений сердца на 5—10 ударов меньше, чем у женщин[B: 6]. «Средняя частота сердечных сокращений в состоянии покоя равна приблизительно 70 ударам в минуту у здоровых взрослых людей, у детей она значительно выше. Во время сна ЧСС уменьшается на 10—20 ударов в минуту, а во время эмоционального возбуждения или мышечной активности может достигать значений, превышающих 100 ударов в минуту. У хорошо тренированных спортсменов в состоянии покоя ЧСС обычно составляет всего лишь 50 ударов в минуту»[4]. Во время сна у атлетов может в норме быть менее 45 ударов в минуту[5].

Иные отклонения от нормального регулярного синусового ритма считаются нарушением ритма сердца, то есть аритмиями[1].

Аритмический регулярный синусовый ритм[править | править код]

Регулярный синусовый ритм с ЧСС более 100 уд/мин определяется как синусовая тахикардия.[6]

У взрослых частота ритма при синусовой тахикардии редко превышает 160 уд/мин; однако у молодых людей при максимальной физиологической или фармакологической стимуляции нормальный синусовый узел способен возбуждаться с частотой более 180 уд/мин[1][6], и только во время максимальной физической нагрузки частота может достигать 200 уд/мин[1].

Максимальные ЧСС обычно находятся в диапазоне 200—220 ударов в минуту, хотя встречаются некоторые крайние случаи, когда ЧСС может достигать более высоких значений.[7] С возрастом способность генерировать максимальные показатели снижается; приблизительные оценки возрастного максимума ЧСС можно получить, вычтя возраст человека из 220: например, можно ожидать, что у 40-летнего индивида ЧСС достигнет максимального показателя приблизительно 180, а у 60-летнего — 160 уд/мин[7].

У здоровых лиц синусовая тахикардия наблюдается во время физической нагрузки, пищеварения, при эмоциях (радость, страх) и т. п.[1]

Аритмический нерегулярный синусовый ритм[править | править код]

Среди нерегулярных видов синусового ритма, обобщённо обозначаемых как дисфункция (слабость) синусового узла, выделяют: 1) брадикардия, 2) остановка, 3) нерегулярность, 4) хронотропная некомпетентность, 5) блокада выхода из синусового узла.[5]

Более редкий ритм синусового узла называют синусовой брадикардией. При синусовой брадикардии редко бывает ниже 40 в минуту[1].

Остановка синусового узла может приводить к прекращению синусового ритма и к автоматии предсердно-желудочкового узла с возникновением брадикардии более выраженной: при этом ЧСС 40—65 ударов в минуту.[8] Выраженных гемодинамических нарушений при этом может не возникать, и потому без ЭКГ различить виды брадикардии оказывается весьма затруднительно[8].

Патологической синусовая аритмия (нерегулярность) считается при разнице на ЭКГ между соседними РР в 0,12 с и более[1].

Хронотропная некомпетентность определяется при ЧСС ниже 90—100 уд/мин на пике нагрузки[5].

Физиологические механизмы[править | править код]

Автоматизм[править | править код]

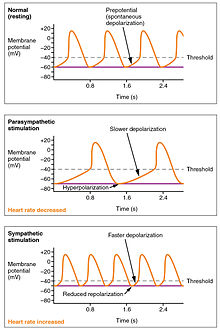

Ритмичная работа сердца обеспечивается способностью специализированных клеток сердца вырабатывать потенциалы действия при отсутствии внешних раздражителей; такую способность возбудимых тканей в физиологии называется автоматизмом[B: 7][9][B: 8][B: 9][B: 10][B: 2].

Физиологическая роль[править | править код]

Основная физиологическая роль ЧСС состоит в поддержании величины минутного объёма кровотока на уровне, адекватном актуальным потребностям организма.

Сердечный выброс — это количество крови, которое сердце прокачивает в минуту. Он может изменяться при изменении частоты ударов сердца (то есть частоты сердечных сокращений) или объёма крови, выталкиваемого из одного желудочка за одно сокращение (систолический объём, СО). Математически сердечный выброс можно представить в виде их произведения:

- Сердечный выброс = ЧСС × СО.[4]

Постоянная тахикардия может выступать в качестве компенсаторного механизма для увеличения сердечного выброса при уменьшенном ударном (систолическом) объёме из-за значительного поражения миокарда (например, при инфаркте миокарда)[A: 1].

Однако притом ЧСС является также и одним из важнейших факторов, определяющих потребность миокарда в кислороде, которая повышается при тахикардии, — что может привести к развитию ишемии миокарда[A: 1]. И, наоборот, урежение ЧСС может существенно повышать порог ишемии[A: 1].

ЧСС может быть важным фактором в патогенезе коронарного атеросклероза: экспериментально показано, что урежение ЧСС приводило к меньшему атеросклеротическому поражению сосудов, чем при частом ритме[A: 1].

Нормальная регуляция[править | править код]

Деятельность сердца регулируется комплексом воздействий со стороны метаболитов, гуморальных факторов и нервной системы.[B: 11][10][B: 12][11]

«Способность сердца к адаптации обусловлена двумя типами регуляторных механизмов:[12]

- внутрисердечной регуляцией (такая регуляция связана с особыми свойствами самого миокарда, благодаря чему она действует и в условиях изолированного сердца) и

- экстракардиальной регуляцией, которую осуществляют эндокринные железы и вегетативная нервная система».

Внутрисердечная регуляция[править | править код]

В качестве примера внутрисердечной саморегуляции можно привести механизм Франка — Старлинга в результате действия которого ударный объём сердца увеличивается в ответ на увеличение объёма крови в желудочках перед началом систолы (конечный диастолический объем), когда все остальные факторы остаются неизменными. Физиологическое значение этого механизма заключается в основном в поддержании равенства объёмов крови, проходящей через левый и правый желудочек. Косвенно этот механизм может влиять и на ЧСС.

Работа сердца существенно модифицируется также и на уровне локальных интракардиальных (кардиально-кардиальных) рефлексов, замыкающихся в интрамуральных ганглиях сердца.[10]

По сути дела внутрисердечные рефлекторные дуги — часть метасимпатической нервной системы. Эфферентные нейроны являются общими с дугой классического парасимпатического рефлекса (ганглионарные нейроны), представляя единый «конечный путь» для афферентных влияний

сердца и эфферентной импульсации по преганглионарным эфферентным волокнам блуждающего нерва. Внутрисердечные рефлексы обеспечивают «сглаживание» тех изменений в деятельности сердца, которые возникают за счет механизмов гомео- или гетерометрической саморегуляции, что необходимо для поддержания оптимального уровня сердечного выброса.[11]

Экстракардиальная регуляция[править | править код]

Сердце может быть эффекторным звеном рефлексов, зарождающихся в сосудах, внутренних органах, скелетных мышцах и коже; все эти рефлексы выполняются на уровне различных отделов вегетативной нервной системы, и рефлекторная дуга их может замыкаться на любом уровне, начиная от ганглиев и до гипоталамуса.[10].

Так, рефлекс Гольтца проявляется брадикардией, вплоть до полной остановки сердца, в ответ на раздражение механорецепторов брюшины; рефлекс Данана — Ашнера проявляется урежением ЧСС при надавливании на глазные яблоки; и т. д.[10].

Расположенный в продолговатом мозге сосудодвигательный центр, являющийся частью вегетативной нервной системы, получает сигналы от различных рецепторов: проприорецепторов, барорецепторов и хеморецепторов, — а также стимулы от лимбической системы. В совокупности эти входные сигналы обычно позволяют сосудодвигательному центру достаточно точно регулировать работу сердца через процессы, известные как сердечные рефлексы[7].

В качестве примера рефлексов сосудодвигательного центра можно привести барорефлекс (рефлекс Циона — Людвига): при повышении артериального давления увеличивается частота импульсации барорецепторов, а сосудодвигательный центр уменьшают симпатическую стимуляцию и увеличивают парасимпатическую стимуляцию, что приводит, в частности, и к уменьшению ЧСС; и, наоборот, по мере снижения давления скорость срабатывания барорецепторов уменьшается, и сосудодвигательный центр увеличивает симпатическую стимуляцию и снижает парасимпатическую, что приводит, в частности, и к увеличению ЧСС.

Существует аналогичный рефлекс, называемый предсердным рефлексом или рефлексом Бейнбриджа, в котором задействованы специализированные барорецепторы предсердий.

Волокна правого блуждающего нерва иннервируют преимущественно правое предсердие и особенно обильно СУ; вследствие этого влияния со стороны правого блуждающего нерва проявляются в отрицательном хронотропном эффекте, т. е. уменьшают ЧСС.[10].

К экстракардиальной регуляции относят также гормональные влияния[10]. Так, гормоны щитовидной железы (тироксин и трийодтиронин) усиливают сердечную деятельность, способствуя более частой генерации импульсов, увеличению силы сердечных сокращений и усилению транспорта кальция; тироидные гормоны повышают и чувствительность сердца к катехоламинам — адреналину, норадреналину[11].

В качестве примера воздействия метаболитов можно привести воздействие повышенной концентрации ионов калия, которая оказывает на сердце влияние, подобное действию блуждающих нервов: избыток калия в крови вызывает урежение ритма сердца, ослабляет силу сокращения, угнетает проводимость и возбудимость[11].

Патофизиологическая интоксикация[править | править код]

Интоксикация (отравление) различными веществами может приводить к нарушению нормального ритма сердца[1]; так, например, ведут

- к тахикардии: алкоголь, никотин, атропин;

- к брадикардии:

- желтуха, уремия,

- инфекции (брюшной тиф и др.);

- медикаментозные (гликозиды, бета-блокаторы, резерпин, гуанетидин, хинидин, морфин);

- отравление грибами.

Клиническая значимость[править | править код]

Значимость ЧСС для клинической медицины невелика: отличить нормальный регулярный синусовый ритм от любого его нарушения. Затем для более точного диагноза приходится использовать иные методы, — в первую очередь электрокардиографию.

Вместе с тем, оценка вариабельности ритма сердца позволяет проводить донозоологическую (доврачебную) диагностику[B: 13].

Было выявлено[A: 1], что ЧСС имеет самостоятельное значение как прогностический фактор для оценки риска развития и осложнённого течения ишемической болезни сердца (ИБС). Показано, что риск смерти от всех причин резко возрастал у лиц с ЧСС в покое более 84 уд/мин, причём летальность среди обследованных с ЧСС от 90 до 99 уд/мин была в три раза выше, чем у лиц с ЧСС менее 60 уд/мин, независимо от пола и этнической принадлежности. Обнаружена почти линейная зависимость между снижением ЧСС и уменьшением летальности: урежение ЧСС на каждые 10 уд/мин уменьшает летальность на 15—20 %[A: 1].

См. также[править | править код]

- Аритмия сердца

- Вариабельность сердечного ритма

- Гемодинамика

- Минутный объем кровообращения

- Пульс

- Сердечная деятельность

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Чазов, 1982, с. 470—472.

- ↑ Яковлев, 2003, § 4.12 Диагностика синдрома слабости синусового узла, с. 47—49.

- ↑ Betts, 2013, § 19.2 Cardiac Muscle and Electrical Activity, с. 846—860.

- ↑ 1 2 Academia, 2004, Глава 46. Регуляция сердечных сокращений, с. 571.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Бокерия, 2001, с. 100.

- ↑ 1 2 Мандел, 1996, Тои 1, с. 275—476.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Betts, 2013, § 19.4 Cardiac Physiology, с. 865—876.

- ↑ 1 2 Чазов, 1982, с. 475—476.

- ↑ Сердце // Сафлор — Соан. — М. : Советская энциклопедия, 1976. — С. 294. — (Большая советская энциклопедия : [в 30 т.] / гл. ред. А. М. Прохоров ; 1969—1978, т. 23).

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Филимонов, 2002, § 11.3.3. Регуляция функций сердца, с. 453—463.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Судаков, 2000, Регуляция сердечной деятельности, с. 327—334.

- ↑ Шмидт, 2005, § 19.5. Приспособление сердечной деятельности к различным нагрузкам, с. 485.

Литература[править | править код]

Книги[править | править код]

- ↑ Аритмии сердца. Механизмы. Диагностика. Лечение. В 3 томах / Пер. с англ./Под ред. В. Дж. Мандела. — М.: Медицина, 1996. — 10 000 экз. — ISBN 0-397-50561-2.

- ↑ 1 2 Клиническая аритмология / Под ред. проф. А. В. Ардашева. — М.: МЕДПРАКТИКА-М, 2009. — 1220 с. — 1000 экз. — ISBN 978-5-98803-198-7.

- ↑ Руководство по кардиологии. Т. 3: Болезни сердца / под ред. Е. И. Чазова. — М.: Медицина, 1982. — 624 с.

- ↑ Лекции по кардиологии. В 3-х т. Т.3 / под ред. Л. А. Бокерия, Е. З. Голузовой. — М.: Издательство НЦССХ им. А. Н. Бакулева. РАМН, 2001. — 220 с.

- ↑ Betts J. G., Desaix P. , Johnson E. W., Johnson J. E., Korol O., Kruse D., Poe B., Wise J., Womble M. D., Young K. A. Anatomy and Physiology (англ.). — OpenStax, 2013. — 1410 p. — ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ↑ Гальперин С. И. Физиология человека и животных. — Издание 5-е. — М.: Высшая школа, 1977. — С. 104—105. — 653 с.

- ↑ Большая медицинская энциклопедия / гл. ред. Н. А. Семашко. — М.: Государственное издательство биологической и медицинской литературы, 1936. — Т. 30. — С. 185. — 832 с. — 20 700 экз.

- ↑ Яковлев В. Б. Диагностика лечение нарушений ритма сердца: Пособие для врачей / под ред. В. Б. Яковлев, А. С. Макаренко, К. И. Капитонов. — М.: БИНОМ, 2003. — 168 с. — ISBN 5-94774-077-X.

- ↑ Фундаментальная и клиническая физиология / под ред. А. Камкина, А. Каменского. — М.: Academia, 2004. — 1072 с. — ISBN 5-7695-1675-5.

- ↑ Дудель Й., Рюэгг Й., Шмидт Р. и др. Физиология человека: в 3-х томах. Пер. с англ = Human Physiology / Под ред. Р. Шмидта, Г. Тевса. — 3. — М.: Мир, 2005. — Т. 2. — 314 с. — 1000 экз. — ISBN 5-03-003576-1.

- ↑ Филимонов В. И. Руководство по общей и клинической физиологии. — М.: Медицинское информационное агентство, 2002. — 958 с. — 3000 экз. — ISBN 5-89481-058-2.

- ↑ Физиология. Основы и функциональные системы / под ред. К. В. Судакова. — М.: Медицина, 2000. — 784 с. — ISBN 5-225-04548-0.

- ↑ Баевский Р. М., Берсенева А. П. Введение в донозологическую диагностику. — М.: Слово, 2008. — 174 с. — 1000 экз. — ISBN 978-5-900228-77-8.

Статьи[править | править код]

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Кулешова Э. В. Частота сердечных сокращений как фактор риска у больных ишемической болезнью сердца // Вестник аритмологии : journal. — 1999. — № 13. — С. 75—83. — ISSN 1561-8641.

Нормативные документы[править | править код]

- ↑ ГОСТ 17562-72 Приборы измерительные для функциональной диагностики. Термины и определения. docs.cntd.ru. Дата обращения: 29 апреля 2020.

Определение пульса – это наиболее простой и доступный в любых условиях метод исследования состояния сердечно-сосудистой системы, её резервных возможностей и патологических изменений. Вот почему каждый человек должен научиться его считать.

Определение пульса – это наиболее простой и доступный в любых условиях метод исследования состояния сердечно-сосудистой системы, её резервных возможностей и патологических изменений. Вот почему каждый человек должен научиться его считать.

Что такое пульс? Если приложить палец к тем участкам тела, куда близко подходят крупные артерии (на шее, в области висков, на тыльной стороне стопы и др.), то под пальцем будут ощущаться толчкообразные ритмические колебания стенок этих артерий, которые принято называть артериальным пульсом. Он возникает при каждом сокращении сердца, когда в момент изгнания крови давление в аорте повышается и пульсовая волна распространяется по стенкам артерий вплоть до мельчайших капилляров.

Самая удобная точка для определения пульса в экстремальных ситуациях находится на основной шейной артерии – сонной. Её легко найти, если провести пальцами от заднего угла нижней челюсти вниз по шее, пока пальцы не лягут в углубление рядом с дыхательным горлом, где хорошо прощупывается пульсация сонной артерии.

Но чаще всего пульс определяют на лучевой артерии у основания большого пальца кисти. Для этого указательный, средний и безымянный пальцы накладывают несколько выше лучезапястного сустава, нащупывают артерию и прижимают к кости. При этом кисть обследуемой руки должна располагаться на уровне сердца.

Если пульсовые удары следуют через одинаковые промежутки времени, то пульс считается ритмичным (правильным); в противном случае – аритмичным (неправильным).

Другая важная характеристика пульса – его частота. Для её определения подсчитывают количество ударов за 10 секунд, и полученный результат умножают на 6. При неправильном ритме количество ударов (частоту) пульса необходимо подсчитывать в течение минуты. При этом каждому человеку присуща своя частота пульса. У здоровых людей она всегда соответствует частоте сердечных сокращений и составляет в покое у мужчин – 60-80 ударов в минуту, у женщин – на 5-10 ударов чаще. Но даже в норме под влиянием различных факторов частота пульса колеблется в довольно широких пределах. Так, у здорового взрослого человека наименьшая частота пульса отмечается в положении лёжа, в положении сидя пульс учащается на 4-6 ударов, а в положении стоя – на 10-14 ударов в минуту. Зимой пульс, как правило, несколько реже, чем летом. Меняется его частота и в течение суток: с 8 до 12 часов она максимальная, затем до 14 часов пульс постепенно уряжается, с 15 часов вновь несколько учащается, достигая наибольшей величины к 18-20 часам, а в середине ночи, когда человек спит, пульс наиболее медленный. Пульс заметно учащается после приёма горячей жидкости и пищи, а вот холодные напитки, наоборот, замедляют его.

Колебания частоты пульса связаны также с физической нагрузкой: чем интенсивнее мышечная работа, тем чаще пульс. При этом очень важно знать максимально допустимое значение частоты пульса. Для этого следует вычесть свой возраст из 220. А чтобы узнать свой личный оптимум частоты пульса, нужно умножить разность на 0,7 (или на 0,6, если вам за шестьдесят или вы в плохой физической форме). Для определения нижней границы частоты пульса надо умножить эту разность на 0,5. Например, если вы здоровый 50-летний мужчина, вычитаем 50 из 220 и получаем максимально допустимую частоту пульса 170 ударов в минуту. Умножение 170 на 0,7 даёт результат 119 – оптимальный показатель, которого вы должны придерживаться при любой физической нагрузке. Умножив 170 на 0,5 получаем минимальное значение частоты пульса для вашего возраста – 85 ударов в минуту.

Пульс реже 60 ударов в минуту называется брадикардия. Причиной её возникновения могут быть понижение функции щитовидной железы, некоторые заболевания сердца и др. Однако, урежение пульса, достигаемое с помощью регулярных физических тренировок, является благоприятным для здоровья фактором, так как сердце в этом случае работает более экономично: ударный объём крови возрастает, а сердечные паузы увеличиваются.

От нагнетательной способности сердца в момент сокращения зависит наполнение пульса, то есть наполнение артерии кровью, выбрасываемой сердцем в течение одной систолы (сокращения) желудочка, которое определяется по степени увеличения и уменьшения объёма артерии в момент прохождения пульсовой волны. В соответствии с этим различают пульс полный, дающий ощущение обильного наполнения, а также пустой и нитевидный, которые часто отмечаются при острой сердечно-сосудистой недостаточности.

Heart rate (or pulse rate)[1] is the frequency of the heartbeat measured by the number of contractions of the heart per minute (beats per minute, or bpm). The heart rate can vary according to the body’s physical needs, including the need to absorb oxygen and excrete carbon dioxide, but is also modulated by numerous factors, including (but not limited to) genetics, physical fitness, stress or psychological status, diet, drugs, hormonal status, environment, and disease/illness as well as the interaction between and among these factors.[2] It is usually equal or close to the pulse measured at any peripheral point.

The American Heart Association states the normal resting adult human heart rate is 60-100 bpm.[3] Tachycardia is a high heart rate, defined as above 100 bpm at rest.[4] Bradycardia is a low heart rate, defined as below 60 bpm at rest. When a human sleeps, a heartbeat with rates around 40–50 bpm is common and is considered normal. When the heart is not beating in a regular pattern, this is referred to as an arrhythmia. Abnormalities of heart rate sometimes indicate disease.[5]

Physiology[edit]

Heart sounds of a 16 year old girl immediately after running, with a heart rate of 186 BPM. The S1 heart sound is intensified due to the increased cardiac output.

While heart rhythm is regulated entirely by the sinoatrial node under normal conditions, heart rate is regulated by sympathetic and parasympathetic input to the sinoatrial node. The accelerans nerve provides sympathetic input to the heart by releasing norepinephrine onto the cells of the sinoatrial node (SA node), and the vagus nerve provides parasympathetic input to the heart by releasing acetylcholine onto sinoatrial node cells. Therefore, stimulation of the accelerans nerve increases heart rate, while stimulation of the vagus nerve decreases it.[6]

As water and blood are incompressible fluids, one of the physiological ways to deliver more blood to an organ is to increase heart rate.[5] Normal resting heart rates range from 60 to 100 bpm.[7][8][9][10] Bradycardia is defined as a resting heart rate below 60 bpm. However, heart rates from 50 to 60 bpm are common among healthy people and do not necessarily require special attention.[3] Tachycardia is defined as a resting heart rate above 100 bpm, though persistent rest rates between 80 and 100 bpm, mainly if they are present during sleep, may be signs of hyperthyroidism or anemia (see below).[5]

- Central nervous system stimulants such as substituted amphetamines increase heart rate.

- Central nervous system depressants or sedatives decrease the heart rate (apart from some particularly strange ones with equally strange effects, such as ketamine which can cause – amongst many other things – stimulant-like effects such as tachycardia).

There are many ways in which the heart rate speeds up or slows down. Most involve stimulant-like endorphins and hormones being released in the brain, some of which are those that are ‘forced’/’enticed’ out by the ingestion and processing of drugs such as cocaine or atropine.[11][12][13]

This section discusses target heart rates for healthy persons, which would be inappropriately high for most persons with coronary artery disease.[14]

Influences from the central nervous system[edit]

Cardiovascular centres[edit]

The heart rate is rhythmically generated by the sinoatrial node. It is also influenced by central factors through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.[15] Nervous influence over the heart rate is centralized within the two paired cardiovascular centres of the medulla oblongata. The cardioaccelerator regions stimulate activity via sympathetic stimulation of the cardioaccelerator nerves, and the cardioinhibitory centers decrease heart activity via parasympathetic stimulation as one component of the vagus nerve. During rest, both centers provide slight stimulation to the heart, contributing to autonomic tone. This is a similar concept to tone in skeletal muscles. Normally, vagal stimulation predominates as, left unregulated, the SA node would initiate a sinus rhythm of approximately 100 bpm.[16]

Both sympathetic and parasympathetic stimuli flow through the paired cardiac plexus near the base of the heart. The cardioaccelerator center also sends additional fibers, forming the cardiac nerves via sympathetic ganglia (the cervical ganglia plus superior thoracic ganglia T1–T4) to both the SA and AV nodes, plus additional fibers to the atria and ventricles. The ventricles are more richly innervated by sympathetic fibers than parasympathetic fibers. Sympathetic stimulation causes the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) at the neuromuscular junction of the cardiac nerves. This shortens the repolarization period, thus speeding the rate of depolarization and contraction, which results in an increased heartrate. It opens chemical or ligand-gated sodium and calcium ion channels, allowing an influx of positively charged ions.[16]

Norepinephrine binds to the beta–1 receptor. High blood pressure medications are used to block these receptors and so reduce the heart rate.[16]

Autonomic Innervation of the Heart – Cardioaccelerator and cardioinhibitory areas are components of the paired cardiac centers located in the medulla oblongata of the brain. They innervate the heart via sympathetic cardiac nerves that increase cardiac activity and vagus (parasympathetic) nerves that slow cardiac activity.[16]

Parasympathetic stimulation originates from the cardioinhibitory region of the brain[17] with impulses traveling via the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). The vagus nerve sends branches to both the SA and AV nodes, and to portions of both the atria and ventricles. Parasympathetic stimulation releases the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction. ACh slows HR by opening chemical- or ligand-gated potassium ion channels to slow the rate of spontaneous depolarization, which extends repolarization and increases the time before the next spontaneous depolarization occurs. Without any nervous stimulation, the SA node would establish a sinus rhythm of approximately 100 bpm. Since resting rates are considerably less than this, it becomes evident that parasympathetic stimulation normally slows HR. This is similar to an individual driving a car with one foot on the brake pedal. To speed up, one need merely remove one’s foot from the brake and let the engine increase speed. In the case of the heart, decreasing parasympathetic stimulation decreases the release of ACh, which allows HR to increase up to approximately 100 bpm. Any increases beyond this rate would require sympathetic stimulation.[16]

Effects of Parasympathetic and Sympathetic Stimulation on Normal Sinus Rhythm – The wave of depolarization in a normal sinus rhythm shows a stable resting HR. Following parasympathetic stimulation, HR slows. Following sympathetic stimulation, HR increases.[16]

Input to the cardiovascular centres[edit]

The cardiovascular centre receive input from a series of visceral receptors with impulses traveling through visceral sensory fibers within the vagus and sympathetic nerves via the cardiac plexus. Among these receptors are various proprioreceptors, baroreceptors, and chemoreceptors, plus stimuli from the limbic system which normally enable the precise regulation of heart function, via cardiac reflexes. Increased physical activity results in increased rates of firing by various proprioreceptors located in muscles, joint capsules, and tendons. The cardiovascular centres monitor these increased rates of firing, suppressing parasympathetic stimulation or increasing sympathetic stimulation as needed in order to increase blood flow.[16]

Similarly, baroreceptors are stretch receptors located in the aortic sinus, carotid bodies, the venae cavae, and other locations, including pulmonary vessels and the right side of the heart itself. Rates of firing from the baroreceptors represent blood pressure, level of physical activity, and the relative distribution of blood. The cardiac centers monitor baroreceptor firing to maintain cardiac homeostasis, a mechanism called the baroreceptor reflex. With increased pressure and stretch, the rate of baroreceptor firing increases, and the cardiac centers decrease sympathetic stimulation and increase parasympathetic stimulation. As pressure and stretch decrease, the rate of baroreceptor firing decreases, and the cardiac centers increase sympathetic stimulation and decrease parasympathetic stimulation.[16]

There is a similar reflex, called the atrial reflex or Bainbridge reflex, associated with varying rates of blood flow to the atria. Increased venous return stretches the walls of the atria where specialized baroreceptors are located. However, as the atrial baroreceptors increase their rate of firing and as they stretch due to the increased blood pressure, the cardiac center responds by increasing sympathetic stimulation and inhibiting parasympathetic stimulation to increase HR. The opposite is also true.[16]

Increased metabolic byproducts associated with increased activity, such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen ions, and lactic acid, plus falling oxygen levels, are detected by a suite of chemoreceptors innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. These chemoreceptors provide feedback to the cardiovascular centers about the need for increased or decreased blood flow, based on the relative levels of these substances.[16]

The limbic system can also significantly impact HR related to emotional state. During periods of stress, it is not unusual to identify higher than normal HRs, often accompanied by a surge in the stress hormone cortisol. Individuals experiencing extreme anxiety may manifest panic attacks with symptoms that resemble those of heart attacks. These events are typically transient and treatable. Meditation techniques have been developed to ease anxiety and have been shown to lower HR effectively. Doing simple deep and slow breathing exercises with one’s eyes closed can also significantly reduce this anxiety and HR.[16]

Factors influencing heart rate[edit]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Using a combination of autorhythmicity and innervation, the cardiovascular center is able to provide relatively precise control over the heart rate, but other factors can impact on this. These include hormones, notably epinephrine, norepinephrine, and thyroid hormones; levels of various ions including calcium, potassium, and sodium; body temperature; hypoxia; and pH balance.[16]

Epinephrine and norepinephrine[edit]

The catecholamines, epinephrine and norepinephrine, secreted by the adrenal medulla form one component of the extended fight-or-flight mechanism. The other component is sympathetic stimulation. Epinephrine and norepinephrine have similar effects: binding to the beta-1 adrenergic receptors, and opening sodium and calcium ion chemical- or ligand-gated channels. The rate of depolarization is increased by this additional influx of positively charged ions, so the threshold is reached more quickly and the period of repolarization is shortened. However, massive releases of these hormones coupled with sympathetic stimulation may actually lead to arrhythmias. There is no parasympathetic stimulation to the adrenal medulla.[16]

Thyroid hormones[edit]

In general, increased levels of the thyroid hormones (thyroxine(T4) and triiodothyronine (T3)), increase the heart rate; excessive levels can trigger tachycardia. The impact of thyroid hormones is typically of a much longer duration than that of the catecholamines. The physiologically active form of triiodothyronine, has been shown to directly enter cardiomyocytes and alter activity at the level of the genome.[clarification needed] It also impacts the beta-adrenergic response similar to epinephrine and norepinephrine.[16]

Calcium[edit]

Calcium ion levels have a great impact on heart rate and myocardial contractility: increased calcium levels cause an increase in both. High levels of calcium ions result in hypercalcemia and excessive levels can induce cardiac arrest. Drugs known as calcium channel blockers slow HR by binding to these channels and blocking or slowing the inward movement of calcium ions.[16]

Caffeine and nicotine[edit]

Caffeine and nicotine are both stimulants of the nervous system and of the cardiac centres causing an increased heart rate. Caffeine works by increasing the rates of depolarization at the SA node, whereas nicotine stimulates the activity of the sympathetic neurons that deliver impulses to the heart.[16]

Effects of stress[edit]

Both surprise and stress induce physiological response: elevate heart rate substantially.[18] In a study conducted on 8 female and male student actors ages 18 to 25, their reaction to an unforeseen occurrence (the cause of stress) during a performance was observed in terms of heart rate. In the data collected, there was a noticeable trend between the location of actors (onstage and offstage) and their elevation in heart rate in response to stress; the actors present offstage reacted to the stressor immediately, demonstrated by their immediate elevation in heart rate the minute the unexpected event occurred, but the actors present onstage at the time of the stressor reacted in the following 5 minute period (demonstrated by their increasingly elevated heart rate). This trend regarding stress and heart rate is supported by previous studies; negative emotion/stimulus has a prolonged effect on heart rate in individuals who are directly impacted.[19]

In regard to the characters present onstage, a reduced startle response has been associated with a passive defense, and the diminished initial heart rate response has been predicted to have a greater tendency to dissociation.[20] Current evidence suggests that heart rate variability can be used as an accurate measure of psychological stress and may be used for an objective measurement of psychological stress.[21]

Factors decreasing heart rate[edit]

The heart rate can be slowed by altered sodium and potassium levels, hypoxia, acidosis, alkalosis, and hypothermia. The relationship between electrolytes and HR is complex, but maintaining electrolyte balance is critical to the normal wave of depolarization. Of the two ions, potassium has the greater clinical significance. Initially, both hyponatremia (low sodium levels) and hypernatremia (high sodium levels) may lead to tachycardia. Severely high hypernatremia may lead to fibrillation, which may cause cardiac output to cease. Severe hyponatremia leads to both bradycardia and other arrhythmias. Hypokalemia (low potassium levels) also leads to arrhythmias, whereas hyperkalemia (high potassium levels) causes the heart to become weak and flaccid, and ultimately to fail.[16]

Heart muscle relies exclusively on aerobic metabolism for energy. Severe myocardial infarction (commonly called a heart attack) can lead to a decreasing heart rate, since metabolic reactions fueling heart contraction are restricted.[16]

Acidosis is a condition in which excess hydrogen ions are present, and the patient’s blood expresses a low pH value. Alkalosis is a condition in which there are too few hydrogen ions, and the patient’s blood has an elevated pH. Normal blood pH falls in the range of 7.35–7.45, so a number lower than this range represents acidosis and a higher number represents alkalosis. Enzymes, being the regulators or catalysts of virtually all biochemical reactions – are sensitive to pH and will change shape slightly with values outside their normal range. These variations in pH and accompanying slight physical changes to the active site on the enzyme decrease the rate of formation of the enzyme-substrate complex, subsequently decreasing the rate of many enzymatic reactions, which can have complex effects on HR. Severe changes in pH will lead to denaturation of the enzyme.[16]

The last variable is body temperature. Elevated body temperature is called hyperthermia, and suppressed body temperature is called hypothermia. Slight hyperthermia results in increasing HR and strength of contraction. Hypothermia slows the rate and strength of heart contractions. This distinct slowing of the heart is one component of the larger diving reflex that diverts blood to essential organs while submerged. If sufficiently chilled, the heart will stop beating, a technique that may be employed during open heart surgery. In this case, the patient’s blood is normally diverted to an artificial heart-lung machine to maintain the body’s blood supply and gas exchange until the surgery is complete, and sinus rhythm can be restored. Excessive hyperthermia and hypothermia will both result in death, as enzymes drive the body systems to cease normal function, beginning with the central nervous system.[16]

Physiological control over heart rate[edit]

A study shows that bottlenose dolphins can learn – apparently via instrumental conditioning – to rapidly and selectively slow down their heart rate during diving for conserving oxygen depending on external signals. In humans regulating heart rate by methods such as listening to music, meditation or a vagal maneuver takes longer and only lowers the rate to a much smaller extent.

[22]

In different circumstances[edit]

Heart rate (HR) (top trace) and tidal volume (Vt) (lung volume, second trace) plotted on the same chart, showing how heart rate increases with inspiration and decreases with expiration.

Heart rate is not a stable value and it increases or decreases in response to the body’s need in a way to maintain an equilibrium (basal metabolic rate) between requirement and delivery of oxygen and nutrients. The normal SA node firing rate is affected by autonomic nervous system activity: sympathetic stimulation increases and parasympathetic stimulation decreases the firing rate.[23]

Resting heart rate[edit]

Normal pulse rates at rest, in beats per minute (BPM):[24]

| newborn (0–1 months old) |

infants (1 – 11 months) |

children (1 – 2 years old) |

children (3 – 4 years) |

children (5 – 6 years) |

children (7 – 9 years) |

children over 10 years & adults, including seniors |

well-trained adult athletes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70-190 | 80–160 | 80-130 | 80-120 | 75–115 | 70–110 | 60–100 | 40–60 |

The basal or resting heart rate (HRrest) is defined as the heart rate when a person is awake, in a neutrally temperate environment, and has not been subject to any recent exertion or stimulation, such as stress or surprise. The available evidence indicates that the normal range for resting heart rate is 50-90 beats per minute.[7][8][9][10] This resting heart rate is often correlated with mortality. For example, all-cause mortality is increased by 1.22 (hazard ratio) when heart rate exceeds 90 beats per minute.[7] The mortality rate of patients with myocardial infarction increased from 15% to 41% if their admission heart rate was greater than 90 beats per minute.[8] ECG of 46,129 individuals with low risk for cardiovascular disease revealed that 96% had resting heart rates ranging from 48 to 98 beats per minute.[9] Finally, in one study 98% of cardiologists suggested that as a desirable target range, 50 to 90 beats per minute is more appropriate than 60 to 100.[10] The normal resting heart rate is based on the at-rest firing rate of the heart’s sinoatrial node, where the faster pacemaker cells driving the self-generated rhythmic firing and responsible for the heart’s autorhythmicity are located.[25] For endurance athletes at the elite level, it is not unusual to have a resting heart rate between 33 and 50 bpm.[citation needed]

Maximum heart rate[edit]

The maximum heart rate (HRmax) is the age-related highest number of beats per minute of the heart when reaching a point of exhaustion[26][27] without severe problems through exercise stress.[28]

In general it is loosely estimated as 220 minus one’s age.[29]

It generally decreases with age.[29] Since HRmax varies by individual, the most accurate way of measuring any single person’s HRmax is via a cardiac stress test. In this test, a person is subjected to controlled physiologic stress (generally by treadmill or bicycle ergometer) while being monitored by an electrocardiogram (ECG). The intensity of exercise is periodically increased until certain changes in heart function are detected on the ECG monitor, at which point the subject is directed to stop. Typical duration of the test ranges ten to twenty minutes.[citation needed]

The theoretical maximum heart rate of a human is 300 bpm, however there have been multiple cases where this theoretical upper limit has been exceeded. The fastest human ventricular conduction rate recorded to this day is a conducted tachyarrhythmia with ventricular rate of 480 beats per minute,[30] which is comparable to the heart rate of a mouse.

Adults who are beginning a new exercise regimen are often advised to perform this test only in the presence of medical staff due to risks associated with high heart rates. For general purposes, a formula is often employed to estimate a person’s maximum heart rate. However, these predictive formulas have been criticized as inaccurate because they generalized population-averages and usually focus on a person’s age and do not even take normal resting pulse rate into consideration. It is well-established that there is a “poor relationship between maximal heart rate and age” and large standard deviations relative to predicted heart rates.[31] (See § Limitations.)

The various formulae provide slightly different numbers for the maximum heart rates by age.

A number of formulas are used to estimate HRmax.

Haskell & Fox (1970)[edit]

Fox and Haskell formula; widely used.

Notwithstanding later research, the most widely cited formula for HRmax (which contains no reference to any standard deviation) is still:[32]

- HRmax = 220 − age

Although attributed to various sources, it is widely thought to have been devised in 1970 by Dr. William Haskell and Dr. Samuel Fox.[33] Inquiry into the history of this formula reveals that it was not developed from original research, but resulted from observation based on data from approximately 11 references consisting of published research or unpublished scientific compilations.[34] It gained widespread use through being used by Polar Electro in its heart rate monitors,[33] which Dr. Haskell has “laughed about”,[33] as the formula “was never supposed to be an absolute guide to rule people’s training.”[33]

While it is the most common (and easy to remember and calculate), this particular formula is not considered by reputable health and fitness professionals to be a good predictor of HRmax. Despite the widespread publication of this formula, research spanning two decades reveals its large inherent error, Sxy = 7–11 bpm. Consequently, the estimation calculated by HRmax = 220 − age has neither the accuracy nor the scientific merit for use in exercise physiology and related fields.[34]

Yet, it is common practice to use 85% of the predicted HRmax (Haskell & Fox) to evaluate chronotropic response to exercise. An ongoing study has found that the 5th percentile of the study cohort maximal heart rate correlates much better with the 85% of predicted HRmax (Haskell & Fox) than the 5th percentile of the study cohort heart rate reserve to the 80% of the predicted heart rate reserve.[citation needed]

Tanaka, Monahan, & Seals (2001)[edit]

From Tanaka, Monahan, & Seals (2001):

- HRmax = 208 − (0.7 × age) [35]

Their meta-analysis (of 351 prior studies involving 492 groups and 18,712 subjects) and laboratory study (of 514 healthy subjects) concluded that, using this equation, HRmax was very strongly correlated to age (r = −0.90). The regression equation that was obtained in the laboratory-based study (209 − 0.7 x age), was virtually identical to that of the meta-study. The results showed HRmax to be independent of gender and independent of wide variations in habitual physical activity levels. This study found a standard deviation of ~10 beats per minute for individuals of any age, meaning the HRmax formula given has an accuracy of ±20 beats per minute.[35]

Robergs & Landwehr (2002)[edit]

A 2002 study[34] of 43 different formulas for HRmax (including that of Haskell and Fox – see above) published in the Journal of Exercise Psychology concluded that:[citation needed]

- no “acceptable” formula currently existed (they used the term “acceptable” to mean acceptable for both prediction of VO2, and prescription of exercise training HR ranges)

- the least objectionable formula (Inbar, et al., 1994) was:

-

- HRmax = 205.8 − (0.685 × age) [36]

- This had a standard deviation that, although large (6.4 bpm), was considered acceptable for prescribing exercise training HR ranges.[citation needed]

Wohlfart, B. and Farazdaghi, G.R. (2003)[edit]

A 2003 study from Lund, Sweden gives reference values (obtained during bicycle ergometry) for men:

- HRmax = 203.7 / ( 1 + exp( 0.033 × (age − 104.3) ) ) [37]

and for women:

- HRmax = 190.2 / ( 1 + exp( 0.0453 × (age − 107.5) ) ) [38]

Oakland University (2007)[edit]

In 2007, researchers at the Oakland University analyzed maximum heart rates of 132 individuals recorded yearly over 25 years, and produced a linear equation very similar to the Tanaka formula, HRmax = 207 − (0.7 × age), and a nonlinear equation, HRmax = 192 − (0.007 × age2). The linear equation had a confidence interval of ±5–8 bpm and the nonlinear equation had a tighter range of ±2–5 bpm[39]

Gulati (for women) (2010)[edit]

Research conducted at Northwestern University by Martha Gulati, et al., in 2010[40] suggested a maximum heart rate formula for women based on 5437 participants:

- HRmax = 206 − (0.88 × age)

Nes, et al. (2013)[edit]

Based on measurements of 3320 healthy men and women aged between 19 and 89, and including the potential modifying effect of gender, body composition, and physical activity, Nes et al found:

- HRmax = 211 − (0.64 × age)[41]

This relationship was found to hold regardless of gender, physical activity status, maximal oxygen uptake, smoking, or body mass index. However, a standard error of the estimate of 10.8 beats/min must be accounted for when applying the formula to clinical settings, and the researchers concluded that actual measurement via a maximal test may be preferable whenever possible.[41]

Limitations[edit]

Maximum heart rates vary significantly between individuals.[33] Even within a single elite sports team, such as Olympic rowers in their 20s, maximum heart rates have been reported as varying from 160 to 220.[33] Such a variation would equate to a 60 or 90 year age gap in the linear equations above, and would seem to indicate the extreme variation about these average figures.[citation needed]

Figures are generally considered averages, and depend greatly on individual physiology and fitness. For example, an endurance runner’s rates will typically be lower due to the increased size of the heart required to support the exercise, while a sprinter’s rates will be higher due to the improved response time and short duration. While each may have predicted heart rates of 180 (= 220 − age), these two people could have actual HRmax 20 beats apart (e.g., 170–190).[citation needed]

Further, note that individuals of the same age, the same training, in the same sport, on the same team, can have actual HRmax 60 bpm apart (160–220):[33] the range is extremely broad, and some say “The heart rate is probably the least important variable in comparing athletes.”[33]

Heart rate reserve[edit]

Heart rate reserve (HRreserve) is the difference between a person’s measured or predicted maximum heart rate and resting heart rate. Some methods of measurement of exercise intensity measure percentage of heart rate reserve. Additionally, as a person increases their cardiovascular fitness, their HRrest will drop, and the heart rate reserve will increase. Percentage of HRreserve is statistically indistinguishable from percentage of VO2 reserve.[42]

- HRreserve = HRmax − HRrest

This is often used to gauge exercise intensity (first used in 1957 by Karvonen).[43]

Karvonen’s study findings have been questioned, due to the following:

- The study did not use VO2 data to develop the equation.

- Only six subjects were used.

- Karvonen incorrectly reported that the percentages of HRreserve and VO2 max correspond to each other, but newer evidence shows that it correlated much better with VO2 reserve as described above.[44]

Target heart rate[edit]

For healthy people, the Target Heart Rate (THR) or Training Heart Rate Range (THRR) is a desired range of heart rate reached during aerobic exercise which enables one’s heart and lungs to receive the most benefit from a workout. This theoretical range varies based mostly on age; however, a person’s physical condition, sex, and previous training also are used in the calculation.[citation needed]

By percent, Fox–Haskell-based[edit]

The THR can be calculated as a range of 65–85% intensity, with intensity defined simply as percentage of HRmax. However, it is crucial to derive an accurate HRmax to ensure these calculations are meaningful.[citation needed]

Example for someone with a HRmax of 180 (age 40, estimating HRmax As 220 − age):

- 65% Intensity: (220 − (age = 40)) × 0.65 → 117 bpm

- 85% Intensity: (220 − (age = 40)) × 0.85 → 154 bpm

Karvonen method[edit]

The Karvonen method factors in resting heart rate (HRrest) to calculate target heart rate (THR), using a range of 50–85% intensity:[45]

- THR = ((HRmax − HRrest) × % intensity) + HRrest

Equivalently,

- THR = (HRreserve × % intensity) + HRrest

Example for someone with a HRmax of 180 and a HRrest of 70 (and therefore a HRreserve of 110):

- 50% Intensity: ((180 − 70) × 0.50) + 70 = 125 bpm

- 85% Intensity: ((180 − 70) × 0.85) + 70 = 163 bpm

Zoladz method[edit]

An alternative to the Karvonen method is the Zoladz method, which is used to test an athlete’s capabilities at specific heart rates. These are not intended to be used as exercise zones, although they are often used as such.[46] The Zoladz test zones are derived by subtracting values from HRmax:

- THR = HRmax − Adjuster ± 5 bpm

- Zone 1 Adjuster = 50 bpm

- Zone 2 Adjuster = 40 bpm

- Zone 3 Adjuster = 30 bpm

- Zone 4 Adjuster = 20 bpm

- Zone 5 Adjuster = 10 bpm

Example for someone with a HRmax of 180:

- Zone 1(easy exercise): 180 − 50 ± 5 → 125 − 135 bpm

- Zone 4(tough exercise): 180 − 20 ± 5 → 155 − 165 bpm

Heart rate recovery[edit]

Heart rate recovery (HRR) is the reduction in heart rate at peak exercise and the rate as measured after a cool-down period of fixed duration.[47] A greater reduction in heart rate after exercise during the reference period is associated with a higher level of cardiac fitness.[48]

Heart rates assessed during treadmill stress test that do not drop by more than 12 bpm one minute after stopping exercise (if cool-down period after exercise) or by more than 18 bpm one minute after stopping exercise (if no cool-down period and supine position as soon as possible) are associated with an increased risk of death.[49][47] People with an abnormal HRR defined as a decrease of 42 beats per minutes or less at two minutes post-exercise had a mortality rate 2.5 times greater than patients with a normal recovery.[48] Another study reported a four-fold increase in mortality in subjects with an abnormal HRR defined as ≤12 bpm reduction one minute after the cessation of exercise.[48] A study reported that a HRR of ≤22 bpm after two minutes “best identified high-risk patients”.[48] They also found that while HRR had significant prognostic value it had no diagnostic value.[48][50]

Development[edit]

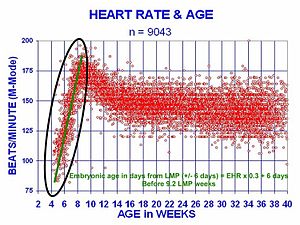

At 21 days after conception, the human heart begins beating at 70 to 80 beats per minute and accelerates linearly for the first month of beating.

The human heart beats more than 2.8 billion times in an average lifetime.[51]

The heartbeat of a human embryo begins at approximately 21 days after conception, or five weeks after the last normal menstrual period (LMP), which is the date normally used to date pregnancy in the medical community. The electrical depolarizations that trigger cardiac myocytes to contract arise spontaneously within the myocyte itself. The heartbeat is initiated in the pacemaker regions and spreads to the rest of the heart through a conduction pathway. Pacemaker cells develop in the primitive atrium and the sinus venosus to form the sinoatrial node and the atrioventricular node respectively. Conductive cells develop the bundle of His and carry the depolarization into the lower heart.[citation needed]

The human heart begins beating at a rate near the mother’s, about 75–80 beats per minute (bpm). The embryonic heart rate then accelerates linearly for the first month of beating, peaking at 165–185 bpm during the early 7th week, (early 9th week after the LMP). This acceleration is approximately 3.3 bpm per day, or about 10 bpm every three days, an increase of 100 bpm in the first month.[52]

After peaking at about 9.2 weeks after the LMP, it decelerates to about 150 bpm (+/-25 bpm) during the 15th week after the LMP. After the 15th week the deceleration slows reaching an average rate of about 145 (+/-25 bpm) bpm at term. The regression formula which describes this acceleration before the embryo reaches 25 mm in crown-rump length or 9.2 LMP weeks is:

Clinical significance[edit]

Manual measurement[edit]

Wrist heart rate monitor (2009)

Heart rate monitor with a wrist receiver

Heart rate is measured by finding the pulse of the heart. This pulse rate can be found at any point on the body where the artery’s pulsation is transmitted to the surface by pressuring it with the index and middle fingers; often it is compressed against an underlying structure like bone. The thumb should not be used for measuring another person’s heart rate, as its strong pulse may interfere with the correct perception of the target pulse.[citation needed]

The radial artery is the easiest to use to check the heart rate. However, in emergency situations the most reliable arteries to measure heart rate are carotid arteries. This is important mainly in patients with atrial fibrillation, in whom heart beats are irregular and stroke volume is largely different from one beat to another. In those beats following a shorter diastolic interval left ventricle does not fill properly, stroke volume is lower and pulse wave is not strong enough to be detected by palpation on a distal artery like the radial artery. It can be detected, however, by doppler.[53][54]

Possible points for measuring the heart rate are:[citation needed]

- The ventral aspect of the wrist on the side of the thumb (radial artery).

- The ulnar artery.

- The inside of the elbow, or under the biceps muscle (brachial artery).

- The groin (femoral artery).

- Behind the medial malleolus on the feet (posterior tibial artery).

- Middle of dorsum of the foot (dorsalis pedis).

- Behind the knee (popliteal artery).

- Over the abdomen (abdominal aorta).

- The chest (apex of the heart), which can be felt with one’s hand or fingers. It is also possible to auscultate the heart using a stethoscope.

- In the neck, lateral of the larynx (carotid artery)

- The temple (superficial temporal artery).

- The lateral edge of the mandible (facial artery).

- The side of the head near the ear (posterior auricular artery).

Electronic measurement[edit]

In obstetrics, heart rate can be measured by ultrasonography, such as in this embryo (at bottom left in the sac) of 6 weeks with a heart rate of approximately 90 per minute.

A more precise method of determining heart rate involves the use of an electrocardiograph, or ECG (also abbreviated EKG). An ECG generates a pattern based on electrical activity of the heart, which closely follows heart function. Continuous ECG monitoring is routinely done in many clinical settings, especially in critical care medicine. On the ECG, instantaneous heart rate is calculated using the R wave-to-R wave (RR) interval and multiplying/dividing in order to derive heart rate in heartbeats/min. Multiple methods exist:[citation needed]

- HR = 1000*60/(RR interval in milliseconds)

- HR = 60/(RR interval in seconds)

- HR = 300/number of “large” squares between successive R waves.

- HR= 1,500 number of large blocks

Heart rate monitors allow measurements to be taken continuously and can be used during exercise when manual measurement would be difficult or impossible (such as when the hands are being used). Various commercial heart rate monitors are also available. Some monitors, used during sport, consist of a chest strap with electrodes. The signal is transmitted to a wrist receiver for display.[citation needed]

Alternative methods of measurement include seismocardiography.[55]

Optical measurements[edit]

Pulse oximetry of the finger and laser Doppler imaging of the eye fundus are often used in the clinics. Those techniques can assess the heart rate by measuring the delay between pulses.[citation needed]

Tachycardia[edit]

Tachycardia is a resting heart rate more than 100 beats per minute. This number can vary as smaller people and children have faster heart rates than average adults.

Physiological conditions where tachycardia occurs:

- Pregnancy

- Emotional conditions such as anxiety or stress.