| η Киля AB | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Двойная звезда | ||||||||||||

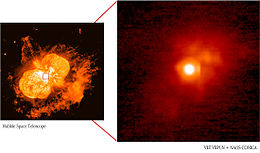

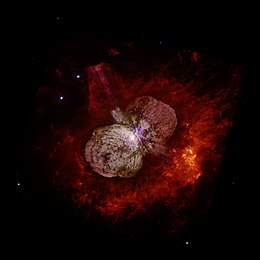

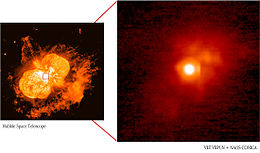

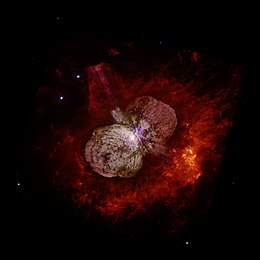

Звезда η Киля — белая точка в центре изображения, на стыке двух лопастей туманности Гомункул. |

||||||||||||

|

Графики временно недоступны из-за технических проблем. |

||||||||||||

| История исследования | ||||||||||||

| Открыватель | Питер Кейзер | |||||||||||

| Дата открытия | 1595—1596 | |||||||||||

| Наблюдательные данные (Эпоха J2000.0) |

||||||||||||

| Тип | двойной переменный гипергигант[1] | |||||||||||

| Прямое восхождение | 10ч 45м 3,59с[2] | |||||||||||

| Склонение | −59° 41′ 4,26″[2] | |||||||||||

| Расстояние | 7500 световых лет (2300 пк) | |||||||||||

| Видимая звёздная величина (V) | от −1,0m до ~7,6m[3] | |||||||||||

| Созвездие | Киль | |||||||||||

| Астрометрия | ||||||||||||

| Лучевая скорость (Rv) | −25,0[4] км/c | |||||||||||

| Собственное движение | ||||||||||||

| • прямое восхождение | −7,6[2] mas в год | |||||||||||

| • склонение | 1,0[2] mas в год | |||||||||||

| Абсолютная звёздная величина (V) | −8,6 (2012)[5] | |||||||||||

| Спектральные характеристики | ||||||||||||

| Спектральный класс | переменная[1] и O[6][7] | |||||||||||

| Показатель цвета | ||||||||||||

| • B−V | +0,61[8] | |||||||||||

| • U−B | −0,45[8] | |||||||||||

| Переменность | ЯГП и двойная | |||||||||||

| Физические характеристики | ||||||||||||

| Радиус | 800 R☉ | |||||||||||

| Элементы орбиты | ||||||||||||

| Период (P) | 2022,7±1,3 суток[9] (5,54 года) лет | |||||||||||

| Большая полуось (a) | 15,4 а. е.[10]″ | |||||||||||

| Эксцентриситет (e) | 0,9[11] | |||||||||||

| Наклонение (i) | 130—145[10]°v | |||||||||||

|

Коды в каталогах SAO 238429, HR 4210, IRAS 10431-5925, 2MASS J10450360-5941040, HD 93308, AAVSO 1041-59, η Car, 1ES 1043-59.4, ALS 1868, CD-59 3306, CEL 3689, CPC 20 3145, CPD-59 2620, CSI-59 2620 41, CSI-59-10431, GC 14799, GCRV 6692, GCRV 6693, HD 93308B, JP11 1994, PPM 339408, RAFGL 4114, TYC 8626-2809-1, eta Car, WDS J10451-5941A, UCAC4 152-053215, 3FHL J1045.1-5941, 3A 1042-595, 4U 1053-58, 4U 1037-60, GPS 1043-595, PBC J1044.8-5942, 2FGL J1045.0-5941, 3FGL J1045.1-5941, 2FHL J1045.2-5942 и WEB 9578 |

||||||||||||

| Информация в базах данных | ||||||||||||

| SIMBAD | * eta Car | |||||||||||

| Звёздная система | ||||||||||||

|

У звезды существует 2 компонента Их параметры представлены ниже: |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Э́та Ки́ля (η Car, η Carinae), Форамен (лат. Foramen), до XVIII века называлась Э́та Корабля Арго, (η Arg, η Argus Navis) — двойная звезда-гипергигант в созвездии Киля с совокупной светимостью компонент более чем в 5 миллионов раз превосходящей солнечную светимость. Находится на расстоянии в 7500 световых лет (2300 парсек). Впервые упоминается как звезда 4-й звёздной величины, но в период с 1837 по 1856 годы в ходе события, известного как «Великая вспышка», значительно увеличила свою яркость. Эта Киля достигла блеска −0,8m и на период с 11 по 14 марта 1843 года стала второй по яркости звездой (после Сириуса) на земном небе, после чего постепенно начала уменьшать светимость, и к 1870-м годам перестала быть видимой невооружённым глазом. Звезда, начиная с 1940 года, снова постепенно увеличивает яркость. К 2014 году она достигла звёздной величины 4,5m. Эта Киля является незаходящей звездой к югу от 30° южной широты, никогда не видна выше 30° северной широты.

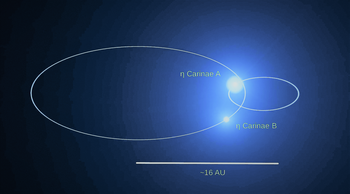

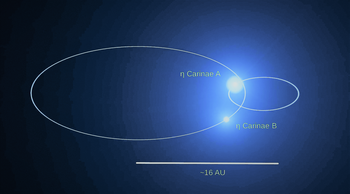

Две звезды в системе Эта Киля движутся вокруг общего центра масс по вытянутым эллиптическим орбитам (эксцентриситет 0,9) с периодом в 5,54 земного года. Основной компонент системы — гипергигант, яркая голубая переменная (ЯГП), изначально обладавшая массой в 150—250 солнечных, из которых утрачено уже около 30 солнечных масс. Это одна из самых больших и неустойчивых известных звёзд, её масса близка к теоретическому верхнему пределу. Как ожидается, в астрономически близком будущем (несколько десятков тысячелетий) она станет сверхновой. Эта Киля А — единственная известная звезда, производящая ультрафиолетовое лазерное[уточнить] излучение. Вторая звезда, η Car B, тоже характеризуется очень высокой поверхностной температурой и светимостью, вероятно спектрального класса O, массой около 30—80 M⊙.

Свет от компонент системы Эта Киля сильно поглощается небольшой биполярной туманностью Гомункул с размерами 12×18 угловых секунд[15], которая состоит из вещества центральной звезды, выброшенного в ходе «Великой вспышки». Масса пыли в Гомункуле оценивается в 0,04 M⊙. Эта Киля А теряет массу настолько быстро, что её фотосфера гравитационно не связана со звездой и «сдувается» излучением в окружающее пространство.

Звезда входит в рассеянное звёздное скопление Трюмплер 16 в гораздо более крупной туманности Киля. Безотносительно к звезде или туманности существует слабый метеорный поток Эта-Кариниды (англ.) (рус. с радиантом, очень близким к звезде на небе.

Звезда имеет современное название Форамен (от лат. foramen «отверстие»), связанное с близкой к звезде туманностью Замочная скважина (NGC 3324).

История наблюдений[править | править код]

Открытие и получение имени звезды[править | править код]

До XVII столетия не существует достоверных записей о наблюдении или открытии Эты Киля, хотя нидерландский мореплаватель Питер Кейзер примерно в 1595—1596 годах описал звезду 4-й величины в месте, приблизительно соответствующем положению Эты Киля. Эти данные были воспроизведены на небесных глобусах Петера Планциуса и Йодокуса Хондиуса и в 1603 году появились в «Уранометрии» Иоганна Байера. Тем не менее, независимый звёздный каталог Фредерика де Хаутмана от 1603 года не включал в себя ни Эту Киля, ни какую-либо другую звезду четвёртой величины в данном регионе. Первое уверенное упоминание об Эте Киля принадлежит Эдмунду Галлею, который описал её в 1677 году как Sequens (то есть «следующую» относительно другой звезды) внутри нового на то время созвездия Дуб Карла. «Каталог Южного неба» Галлея был опубликован в 1679 году[16]. Звезда была также известна под обозначением Байера как Эта Дуба Карла и Эта Корабля Арго[3]. В 1751 году Никола Луи де Лакайль, нанеся на карту «Корабль Арго» и «Дуб Карла», разделил их на несколько меньших созвездий. Звезда оказалась в «килевой» части «Корабля Арго», получившей наименование созвездия Киля[17]. Звезда не была широко известна как Эта Киля вплоть до 1879 года, когда звезды «Корабля Арго» были разнесены по дочерним созвездиям в Аргентинской уранометрии за авторством Б. Гулда[18].

Эта Киля лежит слишком далеко на юге, чтобы быть частью «28 домов» традиционной китайской астрономии, но она включалась в Южные астеризмы, выделенные в XVII столетии. Вместе с s Киля, Лямбдой Центавра и Лямбдой Мухи, Эта Киля формировала астеризм 海山 (Море и Горы)[19]. Эта Киля называлась также Тинь-Шо (天社 — «Небесный алтарь») и Форамен. Также была известна как Хай-Шань-ар (海山二), «вторая звезда Моря и Гор»[20].

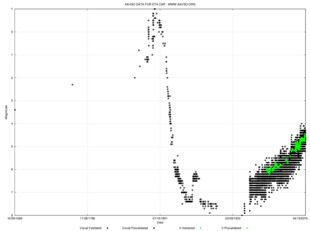

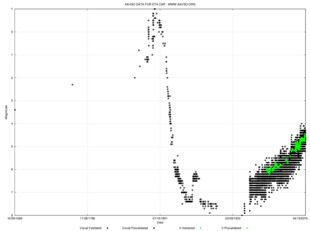

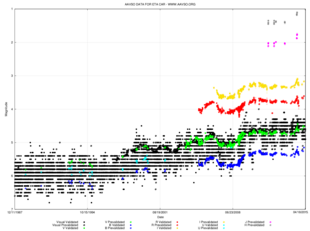

Изменение яркости Эты Киля с ранних наблюдений по сегодняшний день

Галлей упоминал, что звёздная величина примерно равнялась 4 на момент открытия звезды, что соответствует примерно 3,3m на современной шкале. Несколько разрозненных ранних наблюдений позволяют сделать вывод, что звезда в течение большей части 17 столетия не была значимо ярче этой величины[3]. Спорадические наблюдения на протяжении последующих 70 лет тоже упоминают звезду на уровне блеска не ярче 3 величины, однако в 1751 году Лакайль надёжно определяет её яркость на уровне 2m[3]. Есть неясности касательно того, отличалась ли звезда по яркости последующие 50 лет; существуют редкие записи, такие как наблюдение Уильяма Бёрчелла 1815 года, упоминающее Эту Киля как звезду 4-й величины, но не ясно, основаны ли эти записи на оригинальных наблюдениях или являются повтором более ранней информации[3].

«Великая вспышка»[править | править код]

В 1827 году Бёрчелл отметил увеличение яркости Эты Киля до 1-й звёздной величины и стал первым, кто высказал гипотезу о её переменности[3]. Джон Гершель в 1830-х годах проделал серию точных измерений, которая показала, что яркость звезды колебалась в районе 1,4 звёздной величины вплоть до ноября 1837 года. Вечером 16 декабря 1837 года Гершель был поражён тем, что звезда по своей яркости превзошла Ригель[21]. Это событие положило начало 18-летнему периоду в эволюции Эты Киля, известному как «Великая вспышка»[3].

Эта Киля увеличивала свою яркость до января 1838 года, достигнув блеска, примерно равного Альфе Центавра, после чего начала несколько ослабевать в течение последующих 3 месяцев. После этого Гершель покинул Южное полушарие и перестал наблюдать звезду, но получал корреспонденцию от преподобного У. С. МакКея в Калькутте, писавшего ему в 1843 году: «К моему большому удивлению, в марте (1843) я наблюдал, что звезда Эта Корабля Арго стала звездой первой величины и сияет с яркостью Канопуса, а цветом и размерами очень схожа с Арктуром». Наблюдения на Мысе Доброй Надежды показали, что звезда с 11 по 14 марта 1843 года превосходила по яркости Канопус, затем начала меркнуть, но затем вновь стала увеличивать блеск, достигнув уровня яркости между Альфой Центавра и Канопусом с 24 по 28 марта, и снова начала тускнеть[21]. На протяжении большей части 1844 года звезда по яркости находилась посередине между Альфой и Бетой Центавра, то есть её видимый блеск составлял около +0,2m, но к концу года он вновь начал расти. В 1845 году яркость звезды достигла −0,8m, затем −1,0m[5]. Пики яркости, пришедшиеся на 1827, 1838 и 1843 годы, судя по всему, обусловлены прохождением периастра звёздами двойной системы Эта Киля, когда их орбиты проходили ближе всего друг к другу[22]. С 1845 по 1856 яркость падала примерно на 0,1 звёздной величины в год, но с быстрыми и большими колебаниями[5].

С 1857 года яркость уменьшалась быстрыми темпами, пока в 1886 году звёздная система перестала быть видимой невооружённым взглядом. Было показано, что этот эффект был вызван конденсацией пыли из выброшенного вещества, окружающего звезду, а не собственными переменами в светимости[23][24].

Меньшая вспышка[править | править код]

Очередное увеличение яркости началось в районе 1887 года. Звезда достигла отметки в 6,2 звёздной величины к 1892 году, затем к марту 1895 блеск упал до 7,5m[3]. Несмотря на исключительно визуальный характер наблюдений вспышки 1890 года, было подсчитано, что Эта Киля потеряла около 4,3 звёздной величины из-за облаков газа и пыли, выброшенных в ходе предшествовавшей «Великой вспышки». В отсутствие этих помех яркость звёздной системы на тот момент должна была бы достигать около 1,5—1,9 звёздной величины, значительно ярче, чем наблюдавшийся блеск[25]. Это была своего рода уменьшенная копия «Великой вспышки», со значительно меньшими выбросами вещества[26][27].

20-е столетие[править | править код]

Между 1900 и 1940 годом казалось, что Эта Киля перестала меняться в яркости и застыла на уровне 7,6 звёздной величины[3]. Однако в 1953 году было отмечено повышение яркости до 6,5m[28]. Повышение яркости шло стабильно, но с весьма регулярными вариациями в несколько десятых долей звёздной величины[22].

В 1996 году было обнаружено, что вариации яркости проявляют 5,52-летнюю периодичность[22]. Позднее период был уточнён до 5,54 года. Гипотеза о наличии в системе второго компонента была подтверждена наблюдениями за изменениями в радиальной скорости системы, а также за изменением профиля спектральных линий. Наблюдения системы велись в радио-, оптическом и ближнем инфракрасном диапазоне в момент предположительного периастра в конце 1997 и начале 1998 года[29]. В то же время было замечено полное исчезновение рентгеновского излучения от звёздной системы, вызванного эффектом встречного солнечного ветра[30]. Подтверждение существования яркого компаньона у звезды значительно улучшило понимание физических характеристик Эты Киля и её переменности[7].

Неожиданное удвоение яркости в 1998—1999 годах возвратило звёздную систему в зону видимости невооружённым глазом. На момент спектроскопических исследований 2014 года видимая звёздная величина преодолела отметку в 4,5m[31]. Яркость не всегда последовательно меняется на разных длинах волн и не всегда в точности следует 5,4-летнему циклу[32][33]. Радио- и инфракрасные наблюдения, а также наблюдения с орбитальных телескопов расширили возможности по наблюдению за Этой Киля и позволили отследить изменения в спектре[34].

Наблюдения[править | править код]

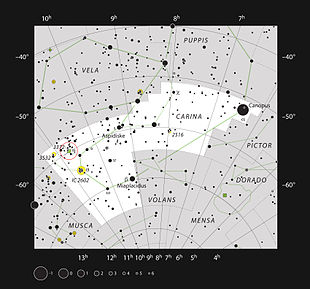

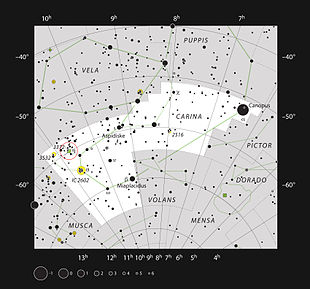

Созвездие Киля. Эта Киля и NGC 3372 (туманность Киля) обведены красным кружком в левой части рисунка

Как звезда, имеющая в настоящее время 4-ю звёздную величину, Эта Киля при отсутствии светового загрязнения хорошо видна невооружённым взглядом[35]. Тем не менее, в историческое время её яркость колебалась в очень широком диапазоне — от второй по яркости на ночном небе в XIX столетии до невидимой невооружённым глазом. Звезда расположена на склонении −59° на южной небесной полусфере, следовательно, её нельзя наблюдать из большей части Евразии и большей части Северной Америки.

Расположенная между Канопусом и Южным Крестом[36], Эта Киля хорошо различима как ярчайшая из звёзд внутри крупной и видной невооружённым взглядом туманности Киля. При наблюдении в любительский телескоп звезда видна внутри V-образной пылевой полосы туманности, имеет оранжевый цвет и не похожа на звёздный объект[37]. Наблюдения при высоком разрешении позволяют увидеть два оранжевых «лепестка» окружающей биполярной отражательной туманности, известной как «Гомункул», простирающиеся в стороны от яркого центрального ядра. Астрономы-любители, отслеживающие переменные звезды, могут сравнить её яркость с несколькими звёздами 4-й и 5-й величины, близкими к туманности.

Радиант обнаруженного в 1961 году слабого метеорного потока Эта-Кариниды очень близок к Эте Киля. Метеорный поток отчётливо наблюдается с 14 по 28 января, с пиком, приходящимся на 21 января. Метеорные дожди никак не связаны с телами вне Солнечной системы, и близость к Эте Киля — простое совпадение[38].

Видимый спектр[править | править код]

Монтаж снимка Эты Киля и туманности Гомункул, сделанный на Космическом телескопе Хаббла (HST), с необычным эмиссионным спектром в ближней ИК области, который снят на спектрографе STIS HST

Ширина и форма спектральных линий Эты Киля обладают значительной изменчивостью, но вместе с тем проявляют целый ряд отличительных особенностей. В спектре Эты Киля ярко выражены эмиссионные линии, обычно широкие, хотя на них и накладывается узкий центральный компонент спектра из плотного ионизированного газа туманности, особенно от глобул Вайгельта (маленьких отражательных туманностей в центре Гомункула). Большинство линий имеют тип профиля звезды P Лебедя (профиль линий, обычный для ярких голубых переменных), но с абсорбцией много более слабой, чем эмиссия. Широкие спектральные линии типа P Лебедя характерны для сильного звёздного ветра, но в данном случае они обладают очень низкой абсорбцией, так как звезда скрыта расширяющейся газовой оболочкой. В крыльях линий можно заметить признаки томсоновского рассеяния на электронах, хотя и слабого, что можно интерпретировать как проявление неоднородной структуры звёздного ветра. Линии водорода сильно выражены, что говорит в пользу того, что Эта Киля сохранила большую часть своей водородной оболочки. Линии HeI[n 1] намного слабее водородных, а отсутствие линий HeII позволяет установить верхний предел на температуру главной звезды. Линии NII идентифицируемы, но слабы, тогда как углеродные линии не обнаружены вовсе, а линии кислорода в лучшем случае крайне слабы, что говорит о горении водорода в ядре через CNO-цикл, который затрагивает и приповерхностные слои. Возможно, одна из наиболее характерных особенностей спектра Эты Киля — значимое присутствие эмиссионных линий FeII, как разрешённых, так и запрещённых; последние возникают при возбуждении газа низкоплотностной туманности вокруг звезды[39][40].

Самые ранние анализы спектра звезды опираются на наблюдения 1869 года, в ходе которых были обнаружены линии «C, D, b, F, с главной зелёной азотной линией». Наблюдатель указал, что линии поглощения не наблюдаются вовсе[41]. Буквенные обозначения даны по Фраунгоферу и соответствуют: Hα, HeI («D» обычно применялось для обозначения двойной линии натрия, но «d» или «D3» было использовано для близкой линии гелия), FeII и Hβ. Предполагается, что последняя указанная линия принадлежит FeII, очень близкая к зелёной линии «небулия», ныне известного как дважды ионизированный кислород, OIII[42].

Фотографические спектры 1893 года описывались как сходные со звездой спектрального класса F5, но со слабыми эмиссионными линиями. Анализ по современным стандартам спектрографии указывает на звезду раннего спектрального класса F. В 1895 году в спектре опять наблюдались сильные эмиссионные линии, при этом линии поглощения присутствовали, но были сильно перекрыты эмиссионными. Такого рода спектральные переходы от сверхгиганта класса F к сильным эмиссионным линиям характерны для новых звёзд, когда выброшенное вещество первоначально излучает как псевдо-фотосфера, а затем, когда оболочка расширяется и становится более тонкой оптически, проявляется эмиссионный спектр излучения[42].

Эмиссионный линейчатый спектр, ассоциированный с плотными звёздными ветрами, продолжал наблюдаться с конца XIX века. Отдельные линии демонстрируют широкие вариации ширины, профиля и доплеровского сдвига, иногда разные скоростные компоненты обнаруживаются внутри одной линии. Спектральные линии меняются также со временем, наиболее сильно с периодом в 5,5 года, но видны и более короткие или длинные периоды с меньшей амплитудой, а также продолжающиеся секулярные (непериодические) изменения[43][44]. Спектр света, отражаемого глобулами Вайгельта, схож в основных чертах с звездой HDE 316285, предельно ярко проявляющей особенности типа P Лебедя и обладающей спектральным классом B0Ieq[45].

Ультрафиолетовый спектр[править | править код]

Ультрафиолетовый спектр системы Эты Киля богат эмиссионными линиями ионизированных металлов, например FeII и CrII, в нём присутствует ярко выраженная линия Лайманα (Lyα) и континуум (излучение непрерывного спектра) от горячего центрального источника. Уровни ионизации и континуум требуют наличие источника с температурой как минимум 37 000 K[46].

Некоторые принадлежащие FeII линии в ультрафиолете необычно сильны. Они локализуются в глобулах Вайгельта и, как считается, вызваны механизмом, схожим по сути с работой лазера с низким коэффициентом усиления. Ионизированный водород между глобулами и центральной звездой генерирует интенсивную Lyα эмиссию, которая проникает в глобулы. Глобулы содержат атомарный водород с малой примесью других элементов, включая фотоионизированное от радиации центральных звёзд железо. Случайный резонанс (когда эмиссионное излучение по совпадению имеет подходящую энергию для накачки возбуждённого состояния) позволяет Lyα эмиссии возбуждать ионы Fe+ до определённого псевдо-метастабильного состояния[47], создавая инверсию населённости, которая в свою очередь вызывает вынужденное излучение[48]. Этот эффект схож по своей сути с мазерной эмиссией в плотных «карманах», окружающих многие холодные сверхгиганты, но последний эффект куда слабее в видимом и УФ спектре, и Эта Киля — единственный достоверный пример ультрафиолетового космического лазера. Подобный эффект от накачки метастабильного состояния OI эмиссией Lyβ в окружающих Эту Киля глобулах также подтверждается как ещё один случай астрофизического УФ лазера[49].

Инфракрасный спектр[править | править код]

Звезды-аналоги, напоминающие Эту Киля, в соседних галактиках

Инфракрасные наблюдения за Этой Киля становятся всё более и более важными. Подавляющее большинство электромагнитной радиации от центральных звёзд поглощается окружающей пылью и затем излучается в среднем и дальнем инфракрасном спектре соответственно температуре пыли. Это позволяет почти всему энергетическому потоку от системы наблюдаться на длине волны, мало подверженной экстинкции, что позволяет делать гораздо более точные оценки светимости, чем в случае остальных экстремально ярких звёзд. Эта Киля — ярчайший источник на небесной сфере в середине инфракрасного спектра[50].

Наблюдения в дальнем инфракрасном спектре позволяют различить огромную массу пыли, обладающую температурой порядка 100—150 K, что позволяет прийти к оценке массы туманности Гомункул как 20 солнечных масс или более. Это куда больше, чем предыдущие оценки, и считается, что вся эта пыль была выброшена в течение нескольких лет во время «Великой вспышки»[51].

Наблюдения в инфракрасном спектре могут проникнуть сквозь пыль и с высокой степенью разрешения наблюдать особенности, полностью невидимые в оптическом диапазоне, однако не сами центральные звёзды. Центральный регион Гомункула содержит меньшие регионы: Малый Гомункул, оставшийся после вспышки 1890-х годов, Бабочку — рассеянные скопления и нити, оставшиеся после двух вспышек, и вытянутую область звёздного ветра[52].

Высокоэнергетическое излучение[править | править код]

Рентгеновское излучение вокруг Эты Киля (красное — низкие энергии, синее — высокие)

В районе Эты Киля было обнаружено несколько источников рентгеновского и гамма-излучения, например 4U 1037-60, входящий в 4-й каталог космической обсерватории «Uhuru», или 1044-59 по каталогу HEAO-2. Самые ранние наблюдения рентгеновского излучения в регионе Эты Киля были сделаны с метеорологической ракеты «Терьер-СэндХоук» (Terrier-Sandhawk), запущенной в США в 1972 году[53], затем они были продолжены на космических обсерваториях «Ariel V»[54], OSO 8[55] и «Uhuru»[56].

Более детальные наблюдения были затем проделаны миссией HEAO-2[57], рентгеновским телескопом ROSAT[58], миссией ASCA[59] и телескопом «Чандра». Было обнаружено множество источников во всём высокоэнергетическом электромагнитном спектре: жёсткие рентгеновские и гамма-лучи внутри области в 1 световой месяц от Эты Киля; жёсткое рентгеновское излучение из центрального района поперечником в 3 световых месяца; отчётливо различимая подковообразная структура протяжённостью 0,67 парсека (2,2 светового года), излучающая низкоэнергетические рентгеновские лучи и соответствующая фронту ударной волны времён «Великой Вспышки»; рассеянное рентгеновское излучение, распределённое по всей площади Гомункула; многочисленные уплотнения и дуги за пределами главного кольца[60][61][62][63].

Всё высокоэнергетическое излучение, ассоциируемое с Этой Киля, варьируется в течение орбитального цикла. В июле и августе 2003 года наблюдался спектральный минимум, или «рентгеновское затмение». В 2009 и 2014 годах наблюдалось схожее по сути событие[64]. Самое высокоэнергетическое гамма-излучение с энергией порядка 100 МэВ было зафиксировано КА AGILE; оно продемонстрировало высокую изменчивость, тогда как гамма-лучи более низкой энергии, наблюдавшиеся КА «Ферми», изменялись слабо[60][65].

Радиоизлучение[править | править код]

Радиоизлучение от Эты Киля в основном наблюдается в микроволновом диапазоне. Оно было обнаружено на длине волн радиолинии нейтрального водорода, однако было более изучено в миллиметровом и сантиметровом диапазонах. В этих диапазонах были обнаружены мазерные линии рекомбинации водорода. Эмиссия сконцентрирована в небольшом неточечном радиоисточнике с поперечником менее чем в 4 угловых секунды; она представляет собой главным образом излучение на свободно-свободных переходах (тепловое тормозное излучение), что совместимо с гипотезой о компактной области HII, обладающей температурой порядка 10 000 K[66]. Более детальные радионаблюдения позволяют различить радиоисточник в виде диска диаметром несколько угловых секунд (10 000 а. е.), окружающий Эту Киля[67].

Для радиоизлучения Эты Киля характерны постоянные изменения в интенсивности и спектральном распределении с циклом в 5,5 года. Интенсивность HII и линий рекомбинации варьируется очень сильно, тогда как эмиссия в континууме (широпоколосное излучение на разных длинах волн) менее подвержена таким изменениям. Это обусловлено резкими снижениями уровня ионизации водорода в течение кратких периодов в каждом цикле, совпадающими со спектроскопическими событиями на других длинах волн[67][68].

Окружающее пространство[править | править код]

Изображение туманности Киля с аннотациями

Эта Киля расположена в глубине туманности Киля, гигантской области звёздного формирования в рукаве Стрельца нашей галактики Млечный Путь. Эта туманность — хорошо заметный невооружённым взглядом объект на южном ночном небе и представляет собой сложное сочетание из эмиссионной, отражательной, и тёмной туманности. Как известно, Эта Киля расположена на одном и том же с туманностью расстоянии от Земли, и отражения её спектра можно увидеть на множестве облаков звездообразования поблизости[69]. Внешний вид туманности Киля, и в частности района «Замочной скважины» значительно изменился с тех пор, как был описан Джоном Гершелем более 150 лет назад[42]. Считается, что это напрямую увязано с сокращением ионизирующего излучения от Эты Киля, начиная с «Великой Вспышки»[70]. До «Великой Вспышки» система Эты Киля вносила около 20 % в ионизацию туманности, но теперь плотно блокирована облаками газа и пыли[69].

Трюмплер 16[править | править код]

Эта Киля расположена внутри рассеянного звёздного скопления Трюмплер 16. Все остальные звезды скопления находятся ниже порога наблюдаемости невооружённым глазом, даже несмотря на то, что WR 25 — ещё одна из экстремально ярких звёзд[71]. Трюмплер 16 и её сосед Трюмплер 14 — два наиболее заметных звёздных скопления в звёздной ассоциации OB1 Киля, крупной группы из ярких и молодых звёзд, объединённых общим движением сквозь пространство[72].

Гомункул[править | править код]

Трёхмерная модель Гомункула

Эта Киля расположена внутри туманности Гомункул и её освещает[73]. В основе своей Гомункул состоит из газа и обломков, исторгнутых в ходе «Великой вспышки» в середине XIX века. Туманность состоит из двух полярных друг к другу «лопастей», выравненных к оси вращения звезды, и экваториальной «юбки». Наблюдения при максимальном разрешении выявляют больше мелких деталей: Малый Гомункул внутри основной туманности, возможно появившийся в ходе вспышки 1890 года; струю; тонкие потоки газа и узелки материи, особо заметные в регионе «юбки»; и три глобулы Вайгельта — плотные газовые облака, расположенные очень близко от звезды[49][74].

Лопасти Гомункула, как считается, были сформированы сразу после первоначальной вспышки с большей вероятностью, чем из предварительно исторгнутой материи или межзвёздной материи, однако дефицит материи вблизи от экваториальной плоскости допускает более позднее взаимодействие между звёздным ветром и исторгнутой материей. Масса Лопастей Гомункула даёт чёткое представление о масштабах «Великой вспышки» с оценками в пределах от 12-15 до 40 солнечных масс извергнутой материи[51][75]. Исследования говорят о том, что материя от «Великой вспышки» больше сконцентрирована в районе полюсов; 75 % массы и 90 % кинетической энергии были исторгнуты выше широты в 45°[76].

Для Гомункула характерна уникальная особенность — возможность получить данные о спектре центрального объекта на разных широтах по его отражению на самых разных участках «лопастей». Это говорит о полярном ветре, когда звёздный ветер быстрее и сильнее на высоких широтах из-за быстрого вращения, вызванного «гравитационным посветлением» в направлении полюсов. В противоположность этому спектр показывает более высокую температуру возбуждения ближе к экваториальной плоскости[77]. Судя по всему, внешние оболочки Эты Киля A не слишком сильно конвективны — иначе бы это предотвратило «гравитационное потемнение». Текущая ось вращения звезды не соответствует выравниванию туманности в пространстве. Скорее всего, это вызвано воздействием Эты Киля B, меняющей наблюдаемый звёздный ветер[78].

Дистанция[править | править код]

Расстояние до Эты Киля было выяснено совмещением различных методов, что дало широко принятую величину в 2 300 пк (7 800 световых лет), с погрешностью около 100 пк (330 световых лет)[79]. Расстояние до Эты Киля не может быть установлено с использованием замеров параллакса из-за большого расстояния и окружающей туманности. Только две звезды находятся на схожем расстоянии в каталоге «Гиппаркос»: HD 93250 в скоплении Трюмплер 16 и HD 93403, другой член Трюмплер 16 или, возможно, Трюмплер 15. Считается, что эти две звезды, на том же расстоянии, что и Эта Киля, сформировались в одном и том же молекулярном облаке, но расстояния до них слишком большие для замеров параллакса. Замеры параллакса для HD 93250 и HD 93403 дают показатели в 0,53 ± 0,42 угловых миллисекунд и 1,22 ± 0,45 угловых миллисекунд соответственно, что даёт расстояние от 2 000 до 30 000 световых лет (от 600 до 9 000 пк)[80]. Как считается, наиболее точные данные о параллаксе удалось получить миссии «Gaia». Первая публикация данных миссии упоминала параллакс в 0,42 ± 0,22 угловых миллисекунд и −0,25 ± 0,33 угловых миллисекунд соответственно для HD 93250 и HD 93204, но не для Эты Киля.

Расстояния до звёздных скоплений можно примерно установить с использованием Диаграммы Герцшпрунга-Рассела или диаграммы цвета-цветности для калибровки данных об абсолютной величине звёзд для подгонки под главную последовательность или идентификации таких особенностей, как принадлежность к «горизонтальной ветви», а значит и их расстояния от Земли. Также необходимо понимать объёмы межзвёздной экстинкции по направлению к звёздному скоплению, что проблематично в случае Эты Киля и схожих областей пространства[81]. Дистанция в 7 330 световых лет (2 250 пк) была получена через поверку светимости звёзд класса O в скоплении Трюмплер 16[82]. После обнаружения межзвёздного покраснения ввиду экстинкции и соответствующей коррекции измерений, расстояние до большинства звёзд Трюмплер 14 и 16 было установлено как 9 500 ± 1000 световых лет (2 900 ± 300 пк)[83].

Известные темпы расширения Гомункула дают необычный геометрический способ замера расстояния. Исходя из того, что лопасти туманности симметричны, проекция туманности на небе зависит от расстояния до неё. Величины в 2 300, 2 250 и 2 300 парсек были установлены для Гомункула и Эты Киля на одном и том же расстоянии[79].

Характеристики[править | править код]

Рентгеновское, оптическое и инфракрасное изображение Эты Киля (26 августа, 2014)

Звёздная система Эты Киля на данный момент одна из самых массивных систем, которые можно детально изучить. До недавнего времени Эта Киля считалась самой массивной из одиночных звёзд, однако в 1996 году двойной характер системы был предположен бразильским астрономом Аугусто Даминиэли[22] и подтверждён в 2005 году[84]. В основной своей части детали звёздной системы затемнены околозвёздной материей, исторгнутой с Эты Киля A, температуру и яркость звезды можно пока установить лишь при наблюдениях в инфракрасном спектре. Быстрые перемены в звёздном ветре в XXI веке позволяют считать, что саму звезду мы сможем увидеть в обозримом будущем, так как её окрестности постепенно очищаются от пыли[85].

Орбита[править | править код]

Двойная природа системы установлена ясно, даже несмотря на невозможность видеть компоненты напрямую или их спектрографически разрешить из-за рассеивания излучения и возбуждений в окружающей туманности. Периодические изменения в фотометрии и спектре побудили поиски компаньона, а моделирование сталкивающихся звёздных ветров и затмения некоторых деталей в спектре системы позволили установить примерные орбиты[10].

Текущий период орбиты компаньона установлен точно как 5,539 лет, несмотря на перемены, связанные с потерей вещества и аккрецией. Орбитальный период между «Великой Вспышкой» и меньшей вспышкой в 1890 году составлял примерно 5,52 лет, тогда как до «Великой Вспышки» был быстрее, возможно между 4,8 и 5,4 годами[13]. Орбитальное расстояние известно лишь примерно, с большой полуосью орбиты около 15-16 а. е. Орбита обладает высоким эксцентриситетом, e = 0,9. Это означает, что расстояние между звёздами составляет иногда около 1,6 а. е., примерно как расстояние между Марсом и Солнцем, а иногда 30 а. е., как расстояние до Нептуна[10].

Возможно, ценнейшее в знании орбит системы из двух звёзд — это возможность напрямую вычислить массу звёзд в паре. Это требует знания точных параметров орбиты и её наклонения. Большинство параметров орбиты в системе Эты Киля точно не известны из-за того, что звёзды нельзя увидеть напрямую и различить. Наклонение же предполагается на уровне 130—145 градусов, что и является важным препятствием к уточнению массы компонентов[10].

Классификация[править | править код]

Эта Киля A классифицируется как яркая голубая переменная (ЯГП) из-за отличительных колебаний в спектре и яркости. Этот тип переменных звёзд характеризуется нерегулярными переменами от высокотемпературного состояния покоя к низкотемпературным вспышкам при примерно постоянной светимости. ЯГП в состоянии покоя находятся на узкой «полосе нестабильности звёзд типа S Золотой Рыбы», туда входят самые яркие и горячие звёзды. Во время вспышек все ЯГП обладают примерно одной температурой, около 8 000 K. ЯГП в ходе типичной вспышки становится визуально ярче, чем в состоянии покоя, при том что болометрическая светимость остаётся без перемен.

Событие, схожее с «Великой вспышкой», произошедшей на Эте Киля A, было замечено за историю наблюдений в Млечном пути пока только раз — на P Лебедя — и в нескольких вероятных ЯГП в других галактиках. Но ни одна из вспышек не достигала такой же силы, как у Эты Киля. Досконально неизвестно, является ли это особенностью самых массивных ЯГП, связано ли с близостью компаньона, или это краткая, но общая для крупных звёзд фаза жизни. Многие схожие события в остальных галактиках были ошибочно приняты за взрывы сверхновых, за что и названы «псевдосверхновыми», в эту группу могут входить и звёзды с иными переходными процессами нетермического характера, приближающие звезду по яркости к сверхновой[51].

Эта Киля A — нетипичная ЯГП. Она обладает большей светимостью, чем любая другая ЯГП в Млечном Пути, хотя может быть сопоставима с «псевдосверхновыми», обнаруженными в иных галактиках. В данный момент звезда не находится в «полосе нестабильности S Золотой Рыбы», хотя до сих пор не ясен температурный или спектральный класс основной звезды, сама «Великая вспышка» была несколько более холодная, чем типичная вспышка ЯГП. Вспышка 1890-х была более похожа на типичную вспышку ЯГП с ранним спектральным типом F, и, как считается сейчас — звезда обладает непрозрачным звёздным ветром, формирующим псевдофотосферу с температурами в районе 9 000 — 14 000 K, что тоже типично для ЯГП в ходе вспышки[23].

Эта Киля B — это массивная и яркая звезда, о которой мало что достоверно известно. Судя по отдельным и нехарактерным для основной звезды эмиссионным линиям в спектре, Эта Киля B может являться молодой звездой спектрального класса O. Множество авторов также полагают, что звезда представляет собой либо сверхгигант, либо просто гигант, хотя не исключают и принадлежность звезды к классу Вольфа-Райе[84].

Масса[править | править код]

Массу звёзд в системе сложно установить, не зная с точностью все элементы орбиты. Эта Киля — двухкомпонентная система, но нет точных данных по орбитам звёзд. Достоверно можно сказать только, что масса центральной звезды вряд ли менее 90 солнечных, исходя из eё высокой светимости[39]. Стандартная модель системы предполагает массу центральной звезды в 100—120 солнечных[12][13] и массу спутника в 30-60 масс Солнца[13][86].

Большая масса предполагается для моделирования энерговыхода и массообмена «Великой вспышки» с общей массой двойной системы в 250 солнечных масс до первой вспышки[13]. Эта Киля потеряла огромную часть массы в ходе вспышки и, как считается, изначально обладала массой между 150 и 250 солнечными, хотя возможно во вспышку внёс вклад и компаньон звезды[87][88].

Потеря массы[править | править код]

Туманность Киля. Эта Киля — яркая звезда на левой стороне изображения.

Потеря массы — один из наиболее интенсивно изучаемых аспектов существования массивных звёзд. Простая вставка с использованием наблюдаемых масштабов утраты массы в лучшие модели звёздной эволюции не отвечает наблюдаемым характеристикам эволюционирующих массивных звёзд вроде Вольфа-Райе, числу и типам сверхновых или их прародителей. Чтобы соответствовать наблюдениям, модели требуют намного более высоких объёмов потери массы. Эта Киля A обладает высочайшими объёмами утраты массы, сейчас примерно 10−3 солнечных масс в год, и является очевидным кандидатом для исследований[89].

Эта Киля A теряет так много массы благодаря мощнейшей светимости и относительно слабой поверхностной гравитации. Её звёздный ветер совершенно непрозрачен и проявляется в виде псевдофотосферы. Это оптически плотное явление блокирует истинную поверхность звезды. Во время «Великой вспышки» уровень потери массы был в тысячу раз больше, около 1 солнечной массы в год, на протяжении десяти или более лет. Совокупная потеря в массе на протяжении вспышки составляет порядка 10-20 солнечных масс, что и позволило сформироваться Гомункулу. Меньшая вспышка в 1890-х создала Малого Гомункула, намного меньшую потерю массы — всего 0,1 солнечной массы[14]. Большая часть вещества покидает Эту Киля на скорости около 420 км/с, но некоторая материя уносится звёздным ветром на скорости до 3 200 км/с, возможно эта материя исторгается звездой-спутником из аккреционного диска[90].

Эта Киля B тоже теряет массу через звёздный ветер, но напрямую это наблюдать невозможно. Модели излучения, вызванного столкновением двух звёздных ветров, говорят о темпе уноса массы в районе 10−5 солнечных масс в год на скорости до 3 000 км/с, что типично для горячих звёзд класса O[62]. На части высокоэксцентричной орбиты второй компонент системы получает материал с Эты Киля А через аккрецию. В ходе «Великой вспышки» на центральной звезде, звезда-спутник аккрецировала несколько солнечных масс вещества и исторгнула мощные струи, которые и сформировали биполярный облик туманности Гомункул[89].

Светимость[править | править код]

Компоненты в двойной системе Эты Киля полностью скрыты пылью и непрозрачным звёздным ветром, с большей частью ультрафиолетового и визуального излучения смещёнными к инфракрасному спектру. Суммарное электромагнитное излучение всех длин волн для обоих компонентов системы составляет несколько миллионов светимостей Солнца[91]. Наилучшая оценка светимости для центральной звезды — 5 миллионов солнечных. Светимость Эты Киля B неизвестна с достаточной точностью, возможно несколько сот тысяч — но не более миллиона.

Наиболее достойная внимания особенность Эты Киля — мощнейшая вспышка псевдосверхновой, произошедшая на центральной звезде в 1843 году. Несколько лет после этого звезда производила столько же света, сколько неяркая сверхновая, и при этом осталась существовать. Было подсчитано, что пиковая светимость системы достигала 50 миллионов солнечных[51]. Несколько похожих случаев было зафиксировано в других галактиках, для примера, событие SN 1961v в галактике NGC 1058[92] и SN 2006jc в галактике UGC 4904[93].

После «Великой вспышки» Эта Киля была затемнена исторгнутой материей, что привело к смещению визуального излучения к красной части спектра. Звезда потеряла примерно 4 звёздные величины на визуальной длине волн, это означает, что звезда вернулась к яркости до вспышки[94]. Эта Киля по-прежнему более яркая именно в инфракрасном спектре, даже несмотря на предполагаемые горячие звезды прямо за туманностью. Современное увеличение яркости звезды вызвано уменьшением экстинкции и рассеиванием пыли из системы, либо уменьшением выброса массы, но не собственно увеличением яркости звезды[85].

Температура[править | править код]

Изображение Гомункула, полученное КА Хаббл, совмещённое с инфракрасным изображением Эты Киля, сделанным телескопом VLT.

До конца 20-го столетия температура Эты Киля составляла, как полагалось, свыше 30 000 К из-за испытывающих «максимумы» спектральных линий, но остальные аспекты спектра позволяли полагать более низкие температуры, поэтому были созданы модели, объясняющие это[95]. Теперь известно, что система Эты Киля состоит из двух звёзд с сильными звёздными ветрами и зоной их столкновения, расположенной внутри пылевой туманности, которая перенаправляет 90 % электромагнитного излучения в средний и дальний инфракрасный участки спектра. Из-за этих особенностей установить точную температуру центральной звезды или её компаньона проблематично.

Мощные звёздные ветра сталкиваются внутри пылевой туманности, что становится причиной температур в 100 МК (мегакельвинов) на вершине конуса столкновения между двумя звёздами. Эта зона излучает в жёстком рентгеновском спектре и гамма-излучении вблизи от звёзд. Вблизи от периастра вторая звезда проходит через более плотные слои звёздного ветра от центральной звезды, и зона столкновения ветров испытывает пертурбации, закручиваясь в спираль, тянущуюся за Эта Киля B[96].

Зона столкновения ветров разделяет звёздные ветра от двух звёзд. На уровне 55 — 75° позади второй звезды слабый и горячий ветер, типичный для звёзд спектрального класса O или для звёзд Вольфа-Райе. Это позволяет обнаружить некоторое излучение от Эты Киля B, а также с некоторой точностью установить её температуру благодаря спектральным линиям, которые точно не принадлежат любому другому источнику. Несмотря на отсутствие прямых наблюдений для компаньона звезды, есть широко распространённое допущение для моделей, где звезда обладает температурой между 37 000 K и 41 000 К[7].

На всех иных направлениях по другую сторону зоны столкновения ветров распространяется звёздный ветер с Эты Киля A, куда более холодный и более чем в 100 раз более плотный, чем ветер с Эты Киля B. Помимо этого, он оптически плотен, полностью скрывает детали подлинной звёздной фотосферы центральной звезды и сильно усложняет любое определение и без того спорной температуры. Наблюдаемое излучение происходит из псевдофотосферы — где оптическая плотность звёздного ветра стремится к нулю и Росселандова прозрачность составляет 2⁄3. Псевдофотосфера при наблюдении выглядит удлинённой и особо горячей вдоль предполагаемой оси вращения[97].

Во времена Эдмунда Галлея Эта Киля A скорее всего была гипергигантом спектрального класса B с температурой между 20 000 K и 25 000 K на момент наблюдения. Эффективная температура, определённая для сферического оптически плотного звёздного ветра на расстоянии в несколько сотен солнечных радиусов, должна была быть от 9 400 до 15 000 K, тогда как температура теоретического гидростатического ядра в 60 солнечных радиусов и с оптической глубиной 150 должна была быть порядка 35 200 K[34][85][91][98]. Эффективную температуру видимого внешнего края непрозрачного основного ветра от центральной звезды принимают обычно на уровне 15 000 K — 25 000 K на основании особенностей, видных в визуальном и ультрафиолетовом спектре, которые заметны либо в самом спектре, либо отражены через глобулы Вайгельта[51][14].

Гомункул содержит пыль с температурами от 150 K до 400 K. Это источник почти всего инфракрасного излучения от Эты Киля, делающего её ярким объектом на этих длинах волн[51].

Далее, расширяющийся после «Великой вспышки» газ сталкивается с межзвёздной материей и нагревается до примерно 5 мегакельвинов, создавая слабое рентгеновское излучение, заметное в «подкове» или «кольце»[99][100].

Размеры[править | править код]

Полученное Хабблом изображение Эты Киля, демонстрирующее биполярную туманность Гомункул, окружающую двойную систему

Сложно сказать нечто конкретное о размерах компонентов двойной системы Эты Киля ввиду трудностей с непосредственным наблюдением. У Эты Киля B должна быть чётко различимая фотосфера, а радиус можно установить исходя из принятого спектрального класса звезды. Сверхгигант O класса при светимости в 933 000 солнечных и при температуре в 37 200 K должен быть радиусом в 23,6 солнечных[6].

Размеры Эты Киля A сложно определить даже примерно. У центральной звезды — оптически плотный звёздный ветер, потому классическое понимание звёздной поверхности становится расплывчатым. По одним данным удалось вычислить радиус горячего звёздного ядра с температурой в 35 000 кельвинов (то есть самой звезды внутри оптически плотного звёздного ветра) как 60 солнечных при оптической глубине в 150 вблизи от того, что можно было бы назвать физической поверхностью звезды. Замеры при оптической глубине в 0,67 говорят о радиусе в более 800 солнечных, указывая на раздутый оптически плотный звёздный ветер[39]. На пике «Великой вспышки» радиус, насколько такое понятие применимо к моменту выброса огромной массы материи, колебался в районе 1 400 солнечных, что сопоставимо с размерами крупнейших известных звёзд[101].

Размеры звезды в двойной системе должны соответствовать расстоянию между двумя компаньонами, которое в периастре составляет всего 250 солнечных радиусов. Радиус аккреции второй звезды должен составлять 60 солнечных радиусов, что предполагает сильную аккрецию вблизи от периастра, приводящую к коллапсу звёздного ветра Эты Киля B[13]. Было предположено, что изначальное прояснение с 4-ой звёздной величины до 1-ой относительно постоянной болометрической светимости было нормальной вспышкой ЯГП, хотя и чрезмерно экстремальной для этого класса. Затем звезда-спутник прошла через расширенную фотосферу первой звезды в периастре, вызвав дальнейшее повышение яркости, повышение светимости и уровня потери массы в ходе «Великой вспышки»[101].

Вращение[править | править код]

Скорость вращения массивных звёзд оказывает важное влияние на их эволюцию и прекращение существования. Скорость вращения звёзд класса Эта Киля не может быть напрямую измерена из-за невидимости поверхности. Одинокие массивные звезды относительно быстро прекращают ускоренное вращение из за торможения своими же сильными звёздными ветрами, но есть намёки что и A и B Эты Киля — быстро вращающиеся звезды, приблизившиеся к 90 % от критической скорости вращения. Одна или обе звезды вращаются путём взаимодействия, например за счёт аккреции на второго компонента и орбитального взаимодействия с первичной.[78]

Эволюция[править | править код]

Потенциальная сверхновая[править | править код]

С наибольшей вероятностью следующая сверхновая, наблюдаемая в Млечном Пути, возникнет от неизвестного белого карлика или неприметного красного сверхгиганта, который, вполне вероятно, даже не будет виден невооружённым глазом[102]. Тем не менее, перспектива возникновения сверхновой из такого объекта, как экстремальная по многим параметрам, близкая и хорошо изученная звезда Эта Киля вызывает большой интерес[103].

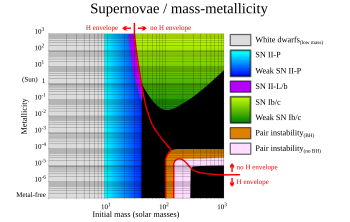

Как правило, коллапс ядра одиночной звезды, первоначально примерно в 150 раз превосходящей по массе Солнце, происходит по сценарию коллапса звезды Вольфа — Райе в течение 3 миллионов лет[104]. Обладая низкой металличностью многие массивные звезды сколлапсируют непосредственно в чёрную дыру без видимого взрыва или образования слабой сверхновой, а небольшая их часть образует редчайший класс парно-нестабильных сверхновых, но при солнечной металличности и выше, как ожидается, потеря массы перед коллапсом будет достаточной для возникновения видимой сверхновой типа Ib или Ic[105]. Если по-прежнему будет оставаться большое количество выброшенного материала вблизи звезды, то ударная волна, образованная взрывом сверхновой и воздействующая на околозвёздное вещество, может эффективно преобразовывать кинетическую энергию в излучение, приводя к образованию сверхмощной сверхновой (SLSN) или гиперновой, в несколько раз более яркой и намного более продолжительной, чем типичная сверхновая, возникшая в результате коллапса ядра. Звезды-прародители большой массы также могут выбрасывать достаточное количество никеля, чтобы вызвать взрыв SLSN просто за счёт радиоактивного распада[106]. Полученный остаток будет чёрной дырой, так как весьма маловероятно, чтобы такая массивная звезда могла потерять достаточную массу, чтобы её ядро не превысило теоретического предела на образование нейтронной звезды[107].

Существование массивного компаньона приносит много других возможностей. Если бы Эта Киля A быстро лишилась своих внешних слоёв, то к началу коллапса она могла бы стать менее массивной звездой типа WC или WO. Это привело бы к возникновению сверхновой звезды типа Ib или типа Ic из-за отсутствия водорода и, возможно, гелия. Считается, что этот тип сверхновой является прародителем некоторых типов гамма-всплесков, но моделирование предсказывает, что они встречаются обычно только в менее массивных звёздах[104][108][109].

Несколько необычных сверхновых и псевдосверхновых были сопоставлены с Эта Киля для анализа её возможной судьбы. Одной из наиболее привлекательных является SN 2009ip — голубой сверхгигант, который в 2009 году стал псевдосверхновой, похожей на «Великую Вспышку» Эта Киля, а затем пережил и ещё более яркий всплеск в 2012 году, который, вероятно, был настоящей сверхновой[110]. Сверхновая SN 2006jc, расположенная на расстоянии около 77 миллионов световых лет в галактике UGC 4904 в созвездии Рыси, также в 2004 году стала яркой псевдосверхновой, а затем взорвалась как сверхновая типа Ib с яркостью 13,8, которую впервые наблюдали 9 октября 2006 года. Эту Киля также сравнили с другими возможными псевдосверхновыми, такими, как SN 1961V, и сверхмощными сверхновыми, такими, как SN 2006gy.

Возможное влияние на Землю[править | править код]

Большинство научных источников считает, что образование гиперновой звезды на расстоянии 7500 световых лет (расстояние до Эты Киля от Солнца) не может нанести какого-либо существенного ущерба земным формам жизни. Может пострадать озоновый слой, могут быть выведены из строя спутники на орбите, может оказаться в опасности жизнь космонавтов, однако всё, что находится на поверхности Земли, будет защищено атмосферой[111].

Типичная сверхновая, образовавшаяся в результате коллапса ядра исходной звезды, расположенной на том же расстоянии, что и Эта Киля, достигла бы пика видимой звёздной величины около −4, как у Венеры. SLSN может быть на пять звёздных величин ярче, как потенциально самая яркая сверхновая в истории (в настоящее время это SN 1006). На расстоянии в 7500 световых лет от звезды взрыв вряд ли непосредственно повлияет на земные формы жизни, поскольку они будут защищены от гамма-лучей атмосферой, а от некоторых других космических лучей — магнитосферой. Основной ущерб будет нанесён верхней части атмосферы, озоновому слою, космическим аппаратам, включая спутники, и любым космонавтам, находящимся в космосе. Есть, по крайней мере, одна работа, в которой предполагается, что в результате взрыва сверхновой возможна полная потеря озонового слоя Земли, что приведёт к значительному увеличению поверхностного УФ-излучения, достигающего поверхности Земли от Солнца. Для этого требуется, чтобы типичная сверхновая была ближе, чем в 50 световых годах от Земли, и даже потенциальной гиперновой для нанесения такого ущерба потребуется быть ближе, чем Эта Киля[111]. В другом анализе возможного воздействия обсуждаются более тонкие эффекты от необычного освещения, такие как подавление мелатонина, что вызовет бессонницу, и повышенный риск развития рака и депрессии. В нём делается вывод о том, что сверхновая такой яркости должна быть намного ближе, чем Эта Киля, чтобы иметь какое-либо серьёзное воздействие на Землю[112].

Ожидается, что Эта Киля не произведёт гамма-всплеск и её ось в настоящее время не направлена на область вблизи Земли, но прямое попадание гамма-всплеска может привести к катастрофическим повреждениям и серьёзному массовому вымиранию. Расчёты показывают, что накопленная энергия такого гамма-всплеска, поразившего земную атмосферу, будет эквивалентна одной килотонне тринитротолуола на квадратный километр по всему полушарию, обращённому к звезде, причём ионизирующее излучение будет в десять раз превышать смертельную дозу облучения всего организма[112].

Примечания[править | править код]

- Комментарии

- ↑ Астрофизическое обозначение для степени ионизации атома, где «I» обозначает нейтральный атом, «II» — однократно ионизированный атом, и т. д.

- Источники

- ↑ 1 2 Skiff B. A. VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Spectral Classifications (Skiff, 2009–2014). Originally published in: Lowell Observatory (October 2014).

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Høg E. et al. The Tycho-2 catalogue of the 2.5 million brightest stars (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2000. — Vol. 355. — P. L27. — Bibcode: 2000A&A…355L..27H.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Frew D. J. The Historical Record of η Carinae I. The Visual Light Curve, 1595–2000 (англ.) // The Journal of Astronomical Data. — 2004. — Vol. 10, no. 6. — P. 1—76. — Bibcode: 2004JAD….10….6F. - ↑ Wilson R. E. General catalogue of stellar radial velocities. — Washington, 1953.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Smith N., Frew D. J. A revised historical light curve of Eta Carinae and the timing of close periastron encounters (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2011. — Vol. 415, no. 3. — P. 2009—2019. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18993.x. — Bibcode: 2011MNRAS.415.2009S. — arXiv:1010.3719.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Verner E. et al. The Binarity of η Carinae Revealed from Photoionization Modeling of the Spectral Variability of the Weigelt Blobs B and D (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2005. — Vol. 624, no. 2. — P. 973. — doi:10.1086/429400. — Bibcode: 2005ApJ…624..973V. — arXiv:astro-ph/0502106.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mehner A. et al. High-excitation Emission Lines near Eta Carinae, and Its Likely Companion Star (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2010. — Vol. 710. — P. 729. — doi:10.1088/0004-637X/710/1/729. — Bibcode: 2010ApJ…710..729M. — arXiv:0912.1067.

- ↑ 1 2 Ducati J. R. VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson’s 11-color system [CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues]. — 2002.

- ↑ Damineli A. et al. The periodicity of the η Carinae events (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2008. — Vol. 384, no. 4. — P. 1649. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12815.x. — Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.384.1649D. — arXiv:0711.4250.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Madura, T. I.; Gull, T. R.; Owocki, S. P.; Groh, J. H.; Okazaki, A. T.; Russell, C. M. P. Constraining the absolute orientation of η Carinae’s binary orbit: A 3D dynamical model for the broad [Fe III] emission (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2012. — Vol. 420, no. 3. — P. 2064. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.20165.x. — Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.420.2064M. — arXiv:1111.2226.

- ↑ Damineli A. et al. Eta Carinae: A long period binary? (англ.) // New Astronomy. — 1997. — Vol. 2, no. 2. — P. 107. — doi:10.1016/S1384-1076(97)00008-0. — Bibcode: 1997NewA….2..107D.

- ↑ 1 2 Clementel N. et al. 3D radiative transfer simulations of Eta Carinae’s inner colliding winds – I. Ionization structure of helium at apastron (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2015. — Vol. 447, no. 3. — P. 2445. — doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2614. — Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.447.2445C. — arXiv:1412.7569.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kashi A., Soker N. Periastron Passage Triggering of the 19th Century Eruptions of Eta Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2010. — Vol. 723. — P. 602. — doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/602. — Bibcode: 2010ApJ…723..602K. — arXiv:0912.1439.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Gull T. R., Damineli A. JD13 – Eta Carinae in the Context of the Most Massive Stars (англ.) // Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. — Cambridge University Press, 2010. — Vol. 5. — P. 373. — doi:10.1017/S1743921310009890. — Bibcode: 2010HiA….15..373G. — arXiv:0910.3158.

- ↑ Крюгель Э., Шустов Б.М. Пыль в космосе // Наука и человечество. — М.: Знание, 1989. — С. 296.

- ↑

Halley E. Catalogus stellarum australium; sive, Supplementum catalogi Tychenici, exhibens longitudines et latitudines stellarum fixarum, quae, prope polum Antarcticum sitae, in horizonte Uraniburgico Tychoni inconspicuae fuere, accurato calculo ex distantiis supputatas, & ad annum 1677 completum correctas…Accedit appendicula de rebus quibusdam astronomicis. — London: T. James, 1679. — С. 13. - ↑ Warner B. Lacaille 250 years on (англ.) // Astronomy and Geophysics. — 2002. — Vol. 43, no. 2. — P. 2.25—2.26. — ISSN 1366-8781. — doi:10.1046/j.1468-4004.2002.43225.x. — Bibcode: 2002A&G….43b..25W.

- ↑ Wagman M. Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. — Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company, 2003. — С. 7—8, 82—85. — ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ↑ 陳久金 (Chen Jiu Jin). Chinese horoscope mythology = zh:中國星座神 (кит.). — 台灣書房出版有限公司 (Taiwan Book House Publishing Co., Ltd.), 2005. — ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ↑ 陳輝樺 (Chen Huihua): 天文教育資訊網. Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy (кит.) (28 июля 2006). Дата обращения: 30 декабря 2012.

- ↑ 1 2 Herschel, John Frederick William. Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope: being the completion of a telescopic survey of the whole surface of the visible heavens, commenced in 1825. — London, United Kingdom: Smith, Elder and Co., 1847. — Т. 1. — С. 33—35.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Damineli A. The 5.52 Year Cycle of Eta Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1996. — Vol. 460. — P. L49. — doi:10.1086/309961. — Bibcode: 1996ApJ…460L..49D.

- ↑ 1 2 Davidson K., Humphreys R. M. Eta Carinae and Its Environment (англ.) // Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics (англ.) (рус.. — Annual Reviews, 1997. — Vol. 35. — P. 1. — doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.35.1.1. — Bibcode: 1997ARA&A..35….1D.

- ↑ Hamacher D. W., Frew D. J. An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. — 2010. — Vol. 13, no. 3. — P. 220—234. — Bibcode: 2010JAHH…13..220H. — arXiv:1010.4610.

- ↑ Humphreys R. M., Davidson K., Smith N. Eta Carinae’s Second Eruption and the Light Curves of the eta Carinae Variables (англ.) // Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. — 1999. — Vol. 111, no. 763. — P. 1124—1231. — doi:10.1086/316420. — Bibcode: 1999PASP..111.1124H.

- ↑ Smith N. The systemic velocity of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2004. — Vol. 351. — P. L15. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07943.x. — Bibcode: 2004MNRAS.351L..15S. — arXiv:astro-ph/0406523.

- ↑ Ishibashi K. et al. Discovery of a Little Homunculus within the Homunculus Nebula of η Carinae (англ.) // The Astronomical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2003. — Vol. 125, no. 6. — P. 3222. — doi:10.1086/375306. — Bibcode: 2003AJ….125.3222I.

- ↑ Thackeray A. D. Stars, Variable: Note on the brightening of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 1953. — Vol. 113, no. 2. — P. 237. — doi:10.1093/mnras/113.2.237. — Bibcode: 1953MNRAS.113..237T.

- ↑ Damineli A. et al. Η Carinae: Binarity Confirmed (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2000. — Vol. 528, no. 2. — P. L101. — doi:10.1086/312441. — Bibcode: 2000ApJ…528L.101D. — arXiv:astro-ph/9912387. — PMID 10600628.

- ↑ Ishibashi K. et al. Recurrent X-Ray Emission Variations of η Carinae and the Binary Hypothesis (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1999. — Vol. 524, no. 2. — P. 983. — doi:10.1086/307859. — Bibcode: 1999ApJ…524..983I.

- ↑ Humphreys R. M. et al. Eta Carinae — Caught in Transition to the Photometric Minimum (англ.) // The Astronomer’s Telegram. — 2014. — Vol. 6368. — P. 1. — Bibcode: 2014ATel.6368….1H.

- ↑ Mehner A., Ishibashi K., Whitelock P., Nagayama T., Feast M., van Wyk F., de Wit W.-J. Near-infrared evidence for a sudden temperature increase in Eta Carinae (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2014. — Vol. 564. — P. A14. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322729. — Bibcode: 2014A&A…564A..14M. — arXiv:1401.4999.

- ↑ Landes H., Fitzgerald M. Photometric Observations of the η Carinae 2009.0 Spectroscopic Event (англ.) // Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. — 2010. — Vol. 27, no. 3. — P. 374. — doi:10.1071/AS09036. — Bibcode: 2010PASA…27..374L. — arXiv:0912.2557.

- ↑ 1 2 Martin J. C. et al. Eta Carinae’s change of state: First new HST/NUV data since 2010, and the first new FUV since 2004 (англ.) // American Astronomical Society. — 2014. — Vol. 223. — P. #151.09. — Bibcode: 2014AAS…22315109M.

- ↑ Bortle J. E. Introducing the Bortle Dark-Sky Scale (англ.) // Sky and Telescope. — 2001. — Vol. 101. — P. 126. — Bibcode: 2001S&T…101b.126B.

- ↑ Thompson M. A Down to Earth Guide to the Cosmos. — Random House, 2013. — ISBN 978-1-4481-2691-0.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. Astronomy. — Dorling Kindersley, 2008. — ISBN 978-1-4053-3620-8.

- ↑ Kronk G. R. Meteor Showers: An Annotated Catalog. — New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. — С. 22. — ISBN 978-1-4614-7897-3.

- ↑ 1 2 3 D. John Hillier. On the Nature of the Central Source in η Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2001. — Vol. 553, no. 837. — P. 837. — doi:10.1086/320948. — Bibcode: 2001ApJ…553..837H.

- ↑ Hillier D. J., Allen D. A. A spectroscopic investigation of Eta Carinae and the Homunculus Nebula. I – Overview of the spectra (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 1992. — Vol. 262. — P. 153. — ISSN 0004-6361. — Bibcode: 1992A&A…262..153H.

- ↑ Le Sueur A. On the Nebulae of Argo and Orion, and on the Spectrum of Jupiter (англ.) // Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. — 1869. — Vol. 18, no. 114—122. — P. 245. — doi:10.1098/rspl.1869.0057. — Bibcode: 1869RSPS…18..245L.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Walborn N. R., Liller M. H. The earliest spectroscopic observations of eta Carinae and its interaction with the Carina Nebula (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1977. — Vol. 211. — P. 181. — doi:10.1086/154917. — Bibcode: 1977ApJ…211..181W.

- ↑ Baxandall F. E. Note on apparent changes in the spectrum of η Carinæ (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 1919. — Vol. 79, no. 9. — P. 619. — doi:10.1093/mnras/79.9.619. — Bibcode: 1919MNRAS..79..619B.

- ↑ Gaviola E. Eta Carinae. II. The Spectrum (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1953. — Vol. 118. — P. 234. — doi:10.1086/145746. — Bibcode: 1953ApJ…118..234G.

- ↑ Gull T. R., Damineli A. JD13 – Eta Carinae in the Context of the Most Massive Stars (англ.) // Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. — Cambridge University Press, 2010. — Vol. 5. — P. 373. — doi:10.1017/S1743921310009890. — Bibcode: 2010HiA….15..373G. — arXiv:0910.3158.

- ↑ Nielsen, K. E.; Ivarsson, S.; Gull, T. R. Eta Carinae across the 2003.5 Minimum: Deciphering the Spectrum toward Weigelt D (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2007. — Vol. 168, no. 2. — P. 289. — doi:10.1086/509785. — Bibcode: 2007ApJS..168..289N.

- ↑ Vladilen Letokhov; Sveneric Johansson. Astrophysical Lasers. — OUP Oxford, 2008. — С. 39. — ISBN 978-0-19-156335-5.

- ↑ Johansson S., Zethson T. Atomic Physics Aspects on Previously and Newly Identified Iron Lines in the HST Spectrum of η Carinae : [англ.]. — Eta Carinae at the Millennium. — 1999. — P. 171. — (ASP Conference Series ; т. 179). — Bibcode: 1999ASPC..179..171J.

- ↑ 1 2 Johansson S., Letokhov V. S. Astrophysical laser operating in the O I 8446-Å line in the Weigelt blobs of η Carinae (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2005. — Vol. 364, no. 2. — P. 731. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09605.x. — Bibcode: 2005MNRAS.364..731J.

- ↑ Mehner A. et al. Near-infrared evidence for a sudden temperature increase in Eta Carinae (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2014. — Vol. 564. — P. A14. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322729. — Bibcode: 2014A&A…564A..14M. — arXiv:1401.4999.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M. Eta Carinae and the Supernova Impostors. — New York, New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. — Т. 384. — С. 26—27. — (Astrophysics and Space Science Library). — ISBN 978-1-4614-2274-7. — doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2275-4.

- ↑ Artigau É. et al. Penetrating the Homunculus—Near-Infrared Adaptive Optics Images of Eta Carinae (англ.) // The Astronomical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2011. — Vol. 141, no. 6. — P. 202. — doi:10.1088/0004-6256/141/6/202. — Bibcode: 2011AJ….141..202A. — arXiv:1103.4671.

- ↑ Hill R. W. et al. A Soft X-Ray Survey from the Galactic Center to VELA (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1972. — Vol. 171. — P. 519. — doi:10.1086/151305. — Bibcode: 1972ApJ…171..519H.

- ↑ Seward F. D. et al. X-ray sources in the southern Milky Way (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 1976. — Vol. 177. — P. 13P. — doi:10.1093/mnras/177.1.13p. — Bibcode: 1976MNRAS.177P..13S.

- ↑ Becker R. H. et al. X-ray emission from the supernova remnant G287.8–0.5 (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1976. — Vol. 209. — P. L65. — doi:10.1086/182269. — Bibcode: 1976ApJ…209L..65B.

- ↑ Forman W. et al. The fourth Uhuru catalog of X-ray sources (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1978. — Vol. 38. — P. 357. — doi:10.1086/190561. — Bibcode: 1978ApJS…38..357F.

- ↑ Seward F. D. et al. X-rays from Eta Carinae and the surrounding nebula (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1979. — Vol. 234. — P. L55. — doi:10.1086/183108. — Bibcode: 1979ApJ…234L..55S.

- ↑ Corcoran M. F., Rawley G. L., Swank J. H., Petre R. First detection of X-ray variability of Eta Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1995. — Vol. 445. — P. L121. — doi:10.1086/187904. — Bibcode: 1995ApJ…445L.121C.

- ↑ Tsuboi Y., Koyama K., Sakano M., Petre R. ASCA Observations of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan (англ.) (рус.. — Astronomical Society of Japan, 1997. — Vol. 49. — P. 85. — doi:10.1093/pasj/49.1.85. — Bibcode: 1997PASJ…49…85T.

- ↑ 1 2 Tavani M. et al. Detection of Gamma-Ray Emission from the Eta-Carinae Region (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2009. — Vol. 698, no. 2. — P. L142. — doi:10.1088/0004-637X/698/2/L142. — Bibcode: 2009ApJ…698L.142T. — arXiv:0904.2736.

- ↑ Leyder J.-C., Walter R., Rauw G. Hard X-ray emission from η Carinae (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2008. — Vol. 477, no. 3. — P. L29. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078981. — Bibcode: 2008A&A…477L..29L. — arXiv:0712.1491.

- ↑ 1 2 Pittard J. M., Corcoran M. F. In hot pursuit of the hidden companion of eta Carinae: An X-ray determination of the wind parameters (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2002. — Vol. 383, no. 2. — P. 636. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020025. — Bibcode: 2002A&A…383..636P. — arXiv:astro-ph/0201105.

- ↑ Weis K., Duschl W. J., Bomans D. J. High velocity structures in, and the X-ray emission from the LBV nebula around η Carinae (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2001. — Vol. 367, no. 2. — P. 566. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20000460. — Bibcode: 2001A&A…367..566W. — arXiv:astro-ph/0012426.

- ↑ Hamaguchi K. et al. X‐Ray Spectral Variation of η Carinae through the 2003 X‐Ray Minimum (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2007. — Vol. 663. — P. 522. — doi:10.1086/518101. — Bibcode: 2007ApJ…663..522H. — arXiv:astro-ph/0702409.

- ↑ Abdo A. A. et al. Fermi Large Area Telescope Observation of a Gamma-ray Source at the Position of Eta Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2010. — Vol. 723. — P. 649. — doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/649. — Bibcode: 2010ApJ…723..649A. — arXiv:1008.3235.

- ↑ Abraham Z. et al. Millimeter-wave emission during the 2003 low excitation phase of η Carinae (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2005. — Vol. 437, no. 3. — P. 977. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041604. — Bibcode: 2005A&A…437..977A. — arXiv:astro-ph/0504180.

- ↑ 1 2 Kashi A., Soker N. Modelling the Radio Light Curve of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2007. — Vol. 378, no. 4. — P. 1609—1618. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11908.x. — Bibcode: 2007astro.ph..2389K. — arXiv:astro-ph/0702389.

- ↑ White S. M., Duncan R. A., Chapman J. M., Koribalski B. The Radio Cycle of Eta Carinae : [англ.] / Edited by R. Humphreys and K. Stanek // The Fate of the Most Massive Stars: Proceedings of the conference held 23-28 May, 2004 in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. — San Francisco : Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 2005. — С. 126. — (ASP Conference Series ; т. 332). — Bibcode: 2005ASPC..332..126W.

- ↑ 1 2 Smith, Nathan. A census of the Carina Nebula – I. Cumulative energy input from massive stars (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2006. — Vol. 367, no. 2. — P. 763. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10007.x. — Bibcode: 2006MNRAS.367..763S. — arXiv:astro-ph/0601060.

- ↑ Smith, N.; Brooks, K. J. The Carina Nebula: A Laboratory for Feedback and Triggered Star Formation (англ.) // Handbook of Star Forming Regions. — 2008. — P. 138. — Bibcode: 2008hsf2.book..138S.

- ↑ Wolk, Scott J.; Broos, Patrick S.; Getman, Konstantin V.; Feigelson, Eric D.; Preibisch, Thomas; Townsley, Leisa K.; Wang, Junfeng; Stassun, Keivan G.; King, Robert R.; McCaughrean, Mark J.; Moffat, Anthony F. J.; Zinnecker, Hans. The Chandra Carina Complex Project View of Trumpler 16 (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2011. — Vol. 194, no. 1. — P. 15. — doi:10.1088/0067-0049/194/1/12. — Bibcode: 2011ApJS..194…12W. — arXiv:1103.1126.

- ↑ Turner, D. G.; Grieve, G. R.; Herbst, W.; Harris, W. E. The young open cluster NGC 3293 and its relation to CAR OB1 and the Carina Nebula complex (англ.) // The Astronomical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 1980. — Vol. 85. — P. 1193. — doi:10.1086/112783. — Bibcode: 1980AJ…..85.1193T.

- ↑ Aitken, D. K.; Jones, B. The infrared spectrum and structure of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 1975. — Vol. 172. — P. 141. — doi:10.1093/mnras/172.1.141. — Bibcode: 1975MNRAS.172..141A.

- ↑ Weigelt, G.; Ebersberger, J. Eta Carinae resolved by speckle interferometry (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 1986. — Vol. 163. — P. L5. — ISSN 0004-6361. — Bibcode: 1986A&A…163L…5W.

- ↑ Gomez, H. L.; Vlahakis, C.; Stretch, C. M.; Dunne, L.; Eales, S. A.; Beelen, A.; Gomez, E. L.; Edmunds, M. G. Submillimetre variability of Eta Carinae: Cool dust within the outer ejecta (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. — 2010. — Vol. 401. — P. L48. — doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2009.00784.x. — Bibcode: 2010MNRAS.401L..48G. — arXiv:0911.0176.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan. The Structure of the Homunculus. I. Shape and Latitude Dependence from H2 and [Fe II] Velocity Maps of η Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2006. — Vol. 644, no. 2. — P. 1151. — doi:10.1086/503766. — Bibcode: 2006ApJ…644.1151S. — arXiv:astro-ph/0602464.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Davidson, Kris; Gull, Theodore R.; Ishibashi, Kazunori; Hillier, D. John. Latitude‐dependent Effects in the Stellar Wind of η Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2003. — Vol. 586. — P. 432. — doi:10.1086/367641. — Bibcode: 2003ApJ…586..432S. — arXiv:astro-ph/0301394.

- ↑ 1 2 Groh, J. H.; Madura, T. I.; Owocki, S. P.; Hillier, D. J.; Weigelt, G. Is Eta Carinae a Fast Rotator, and How Much Does the Companion Influence the Inner Wind Structure? (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2010. — Vol. 716, no. 2. — P. L223. — doi:10.1088/2041-8205/716/2/L223. — Bibcode: 2010ApJ…716L.223G. — arXiv:1006.4816.

- ↑ 1 2 Walborn, Nolan R. The Company Eta Carinae Keeps: Stellar and Interstellar Content of the Carina Nebula // Eta Carinae and the Supernova Impostors. — 2012. — Т. 384. — С. 25—27. — (Astrophysics and Space Science Library). — ISBN 978-1-4614-2274-7. — doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2275-4_2.

- ↑ van Leeuwen, F. Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2007. — Vol. 474, no. 2. — P. 653. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. — Bibcode: 2007A&A…474..653V. — arXiv:0708.1752.

- ↑ The, P. S.; Bakker, R.; Antalova, A. Studies of the Carina Nebula. IV – A new determination of the distances of the open clusters TR 14, TR 15, TR 16 and CR 228 based on Walraven photometry (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. — EDP Sciences, 1980. — Vol. 41. — P. 93. — Bibcode: 1980A&AS…41…93T.

- ↑ Walborn, N. R. The Stellar Content of the Carina Nebula (Invited Paper) (англ.) // Revista Mexicana de Astronomia y Astrofisica Serie de Conferencias. — 1995. — Vol. 2. — P. 51. — Bibcode: 1995RMxAC…2…51W.

- ↑ Hur, Hyeonoh; Sung, Hwankyung; Bessell, Michael S. Distance and the Initial Mass Function of Young Open Clusters in the η Carina Nebula: Tr 14 and Tr 16 (англ.) // The Astronomical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2012. — Vol. 143, no. 2. — P. 41. — doi:10.1088/0004-6256/143/2/41. — Bibcode: 2012AJ….143…41H. — arXiv:1201.0623.

- ↑ 1 2 Iping, R. C.; Sonneborn, G.; Gull, T. R.; Ivarsson, S.; Nielsen, K. Searching for Radial Velocity Variations in eta Carinae (англ.) // American Astronomical Society Meeting 207. — 2005. — Vol. 207. — P. 1445. — Bibcode: 2005AAS…20717506I.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Mehner, Andrea; Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M.; Ishibashi, Kazunori; Martin, John C.; Ruiz, María Teresa; Walter, Frederick M. Secular Changes in Eta Carinae’s Wind 1998–2011 (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2012. — Vol. 751. — P. 73. — doi:10.1088/0004-637X/751/1/73. — Bibcode: 2012ApJ…751…73M. — arXiv:1112.4338.

- ↑ Mehner, A.; Davidson, K.; Humphreys, R. M.; Walter, F. M.; Baade, D.; De Wit, W. J.; Martin, J.; Ishibashi, K.; Rivinius, T.; Martayan, C.; Ruiz, M. T.; Weis, K. Eta Carinae’s 2014.6 spectroscopic event: Clues to the long-term recovery from its Great Eruption (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2015. — Vol. 578. — P. A122. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201425522. — Bibcode: 2015A&A…578A.122M. — arXiv:1504.04940.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Tombleson, Ryan. Luminous blue variables are antisocial: Their isolation implies that they are kicked mass gainers in binary evolution (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2015. — Vol. 447. — P. 598. — doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2430. — Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.447..598S. — arXiv:1406.7431.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan. A blast wave from the 1843 eruption of η Carinae (англ.) // Nature. — 2008. — Vol. 455, no. 7210. — P. 201—203. — doi:10.1038/nature07269. — Bibcode: 2008Natur.455..201S. — arXiv:0809.1678. — PMID 18784719.

- ↑ 1 2 Kashi, A.; Soker, N. Possible implications of mass accretion in Eta Carinae (англ.) // New Astronomy. — 2009. — Vol. 14. — P. 11. — doi:10.1016/j.newast.2008.04.003. — Bibcode: 2009NewA…14…11K. — arXiv:0802.0167.

- ↑ Soker, Noam. Why a Single-Star Model Cannot Explain the Bipolar Nebula of η Carinae (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2004. — Vol. 612, no. 2. — P. 1060. — doi:10.1086/422599. — Bibcode: 2004ApJ…612.1060S. — arXiv:astro-ph/0403674.

- ↑ 1 2 Groh, Jose H.; Hillier, D. John; Madura, Thomas I.; Weigelt, Gerd. On the influence of the companion star in Eta Carinae: 2D radiative transfer modelling of the ultraviolet and optical spectra (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2012. — Vol. 423, no. 2. — P. 1623. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.20984.x. — Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.423.1623G. — arXiv:1204.1963.

- ↑ Stockdale, Christopher J.; Rupen, Michael P.; Cowan, John J.; Chu, You-Hua; Jones, Steven S. The fading radio emission from SN 1961v: evidence for a Type II peculiar supernova? (англ.) // The Astronomical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2001. — Vol. 122, no. 1. — P. 283. — doi:10.1086/321136. — Bibcode: 2001AJ….122..283S. — arXiv:astro-ph/0104235.

- ↑ Pastorello, A.; Smartt, S. J.; Mattila, S.; Eldridge, J. J.; Young, D.; Itagaki, K.; Yamaoka, H.; Navasardyan, H.; Valenti, S.; Patat, F.; Agnoletto, I.; Augusteijn, T.; Benetti, S.; Cappellaro, E.; Boles, T.; Bonnet-Bidaud, J.-M.; Botticella, M. T.; Bufano, F.; Cao, C.; Deng, J.; Dennefeld, M.; Elias-Rosa, N.; Harutyunyan, A.; Keenan, F. P.; Iijima, T.; Lorenzi, V.; Mazzali, P. A.; Meng, X.; Nakano, S.; Nielsen, T. B. A giant outburst two years before the core-collapse of a massive star (англ.) // Nature. — 2007. — Vol. 447, no. 7146. — P. 829. — doi:10.1038/nature05825. — Bibcode: 2007Natur.447..829P. — arXiv:astro-ph/0703663. — PMID 17568740.

- ↑ Smith, Nathan; Li, Weidong; Silverman, Jeffrey M.; Ganeshalingam, Mohan; Filippenko, Alexei V. Luminous blue variable eruptions and related transients: Diversity of progenitors and outburst properties (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2011. — Vol. 415. — P. 773. — doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18763.x. — Bibcode: 2011MNRAS.415..773S. — arXiv:1010.3718.

- ↑ Davidson, K. On the Nature of Eta Carinae (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 1971. — Vol. 154, no. 4. — P. 415. — doi:10.1093/mnras/154.4.415. — Bibcode: 1971MNRAS.154..415D.

- ↑ Madura, T. I.; Gull, T. R.; Okazaki, A. T.; Russell, C. M. P.; Owocki, S. P.; Groh, J. H.; Corcoran, M. F.; Hamaguchi, K.; Teodoro, M. Constraints on decreases in η Carinae’s mass-loss from 3D hydrodynamic simulations of its binary colliding winds (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. — Oxford University Press, 2013. — Vol. 436, no. 4. — P. 3820. — doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1871. — Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.436.3820M. — arXiv:1310.0487.

- ↑ van Boekel, R.; Kervella, P.; SchöLler, M.; Herbst, T.; Brandner, W.; de Koter, A.; Waters, L. B. F. M.; Hillier, D. J.; Paresce, F.; Lenzen, R.; Lagrange, A.-M. Direct measurement of the size and shape of the present-day stellar wind of η Carinae (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics. — EDP Sciences, 2003. — Vol. 410, no. 3. — P. L37. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20031500. — Bibcode: 2003A&A…410L..37V. — arXiv:astro-ph/0310399.

- ↑ Martin, John C.; Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta M.; Mehner, Andrea. Mid-cycle Changes in Eta Carinae (англ.) // The Astronomical Journal. — IOP Publishing, 2010. — Vol. 139, no. 5. — P. 2056. — doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/5/2056. — Bibcode: 2010AJ….139.2056M. — arXiv:0908.1627.

- ↑ Corcoran, Michael F.; Ishibashi, Kazunori; Davidson, Kris; Swank, Jean H.; Petre, Robert; Schmitt, Jurgen H. M. M. Increasing X-ray emissions and periodic outbursts from the massive star Eta Carinae (англ.) // Nature. — 1997. — Vol. 390, no. 6660. — P. 587. — doi:10.1038/37558. — Bibcode: 1997Natur.390..587C.