Текущая версия страницы пока не проверялась опытными участниками и может значительно отличаться от версии, проверенной 16 февраля 2023 года; проверки требует 1 правка.

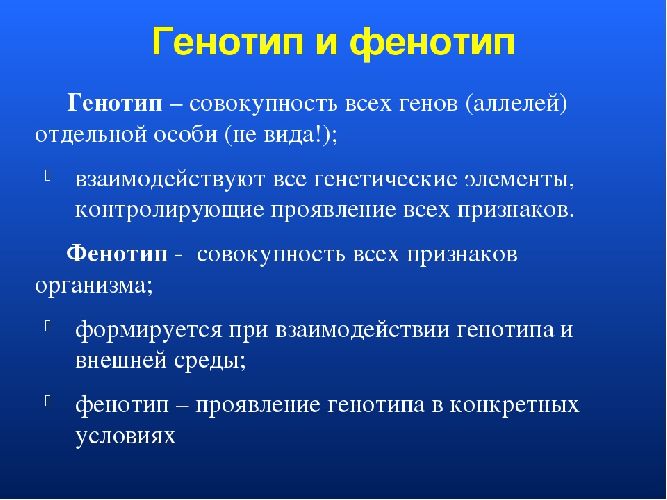

Феноти́п (от др.-греч. φαίνω «являю; обнаруживаю» + τύπος «образец») — совокупность характеристик, присущих индивиду на определённой стадии развития. Фенотип формируется (в процессе феногенеза) на основе генотипа, при участии ряда факторов внешней среды. У гетерозиготных организмов в фенотипе проявляются доминантные гены.

Фенотип — совокупность внешних и внутренних признаков организма, приобретённых в результате онтогенеза (индивидуального развития).

Фен — отдельный вариант признака.

Несмотря на кажущееся строгое определение, концепция фенотипа имеет некоторые неопределённости. Во-первых, большинство молекул и структур, кодируемых генетическим материалом, не заметны во внешнем виде организма, хотя являются частью фенотипа. Например, именно так обстоит дело с группами крови человека. Поэтому расширенное определение фенотипа должно включать характеристики, которые могут быть обнаружены техническими, медицинскими или диагностическими процедурами. Дальнейшее, более радикальное расширение может включать приобретённое поведение или даже влияние организма на окружающую среду и другие организмы. Например, согласно Ричарду Докинзу, плотину бобров также как и их резцы можно считать фенотипом генов бобра.[1]

Фенотип можно определить как «вынос» генетической информации навстречу факторам среды. В первом приближении можно говорить о двух характеристиках фенотипа: а) число направлений выноса характеризует число факторов среды, к которым чувствителен фенотип, — мерность фенотипа; б) «дальность» выноса характеризует степень чувствительности фенотипа к данному фактору среды. В совокупности эти характеристики определяют богатство и развитость фенотипа. Чем многомернее фенотип и чем он чувствительнее, чем дальше фенотип от генотипа, тем он богаче. Если сравнить вирус, бактерию, аскариду, лягушку и человека, то богатство фенотипа в этом ряду растёт.

Генетические факторы, оказывающие влияние на формирование фенотипа[править | править код]

… История любого фенотипа, сохраненного длительным отбором, — это цепь последовательных испытаний его носителей на способность воспроизводить самих себя в условиях непрерывного изменения пространства вариаций их геномов. …

… Не изменения генотипа определяют эволюцию и её направление. Наоборот, эволюция организма определяет изменение его генотипа.— Шмальгаузен И. И. Организм как целое в индивидуальном и историческом развитии. Избранные труды.. — М.: Наука, 1982.

К этим факторам относятся взаимодействие генов из одной (доминирование, рецессивность, неполное доминирование, кодоминирование) и разных (доминантный и рецессивный эпистаз, гипостаз, комплементарность) аллелей, множественные аллели, плейотропное действие гена, доза гена.[2]

Историческая справка[править | править код]

Термин фенотип предложил датский учёный Вильгельм Иогансен в 1909 году вместе с концепцией генотипа, чтобы различать наследственность организма от того, что получается в результате её реализации[3]. Идею о различии носителей наследственности от результата их действия можно проследить уже в работах Грегора Менделя (1865) и Августа Вейсмана. Последний различал (в многоклеточных организмах) репродуктивные и соматические клетки.

Фенотипическая дисперсия[править | править код]

Фенотипическая дисперсия (определяемая генотипической дисперсией) является основной предпосылкой для естественного отбора и эволюции. Организм как целое оставляет (или не оставляет) потомство, поэтому естественный отбор влияет на генетическую структуру популяции опосредованно через вклады фенотипов. Без различных фенотипов нет эволюции. При этом рецессивные аллели не всегда отражаются в признаках фенотипа, но сохраняются и могут быть переданы потомству.

Фенотип и онтогенез[править | править код]

Факторы, от которых зависит фенотипическое разнообразие, генетическая программа (генотип), условия среды и частота случайных изменений (мутации), обобщены в следующей зависимости:

- генотип + внешняя среда + случайные изменения → фенотип

Способность генотипа формировать в онтогенезе, в зависимости от условий среды, разные фенотипы называют нормой реакции. Она характеризует долю участия среды в реализации признака. Чем шире норма реакции, тем больше влияние среды и тем меньше влияние генотипа в онтогенезе. Обычно чем разнообразнее условия обитания вида, тем шире у него норма реакции.

Примеры[править | править код]

Иногда фенотипы в разных условиях сильно отличаются друг от друга. Так, сосны в лесу высокие и стройные, а на открытом пространстве — развесистые. Форма листьев водяного лютика зависит от того, в воде или на воздухе оказался лист.

У людей все клинически определяемые признаки — рост, масса тела, цвет глаз, форма волос, группа крови и т. д. являются фенотипическими.

См. также[править | править код]

- Фен (биология)

- Феном

- Фенетика

- Генотип

- Дисперсия (биология)

- Норма реакции

- Морфа

- Мутация

- Пенетрантность

- Популяция

- Эндофенотип

Литература[править | править код]

- ↑ Ричард Докинз. Расширенный фенотип (англ. The Extended Phenotype). — 1982; переизд., 1999.

- ↑ О.-Я.Л.Бекиш. Медицинская биология. — Витебск: Ураджай, 2000. — С. 141—142.

- ↑ Johannsen W., (1911) «The genotype conception of heredity». Am Nat 45:129-159 [1].

Ссылки[править | править код]

- Михайлов К. Фенотип и генотип в понимании Иогансеном и Камшиловым. Дата обращения: 26 декабря 2016.

Фенотип организма

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 76.

Обновлено 16 Ноября, 2021

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 76.

Обновлено 16 Ноября, 2021

Совокупность внешних и внутренних признаков, свойств и характеристик организма называется фенотипом. Это физическое проявление организма, которое можно наблюдать визуально, без лабораторных исследований генетического кода. Определение фенотипа невозможно представить без генотипа, который оказывает большое влияние на формирование тех или иных характеристик отдельной особи.

Общие сведения

Фенотип — это внешнее физическое проявление организма, совокупность характеристик, присущих индивиду на определённой стадии развития.

Особенность фенотипа в том, что он нагляден и представляет собой любую наблюдаемую характеристику или черту организма, будь то его морфология, развитие, биохимические и физиологические свойства или поведение. Примерами фенотипических признаков являются рост, вес тела, цвет глаз, форма волос, группа крови и пр.

Фенотип является приспособлением генетической информации к факторам окружающей среды. Он обладает двумя основными характеристиками:

- Мерность фенотипа — количество направлений приспособлений указывает на количество факторов среды, к которым чувствителен фенотип.

- Степень приспособления указывает на степень чувствительности фенотипа к данному фактору среды.

Характеристики фенотипа определяют его разнообразие: чем чувствительнее и многослойнее фенотип, тем он богаче.

Фенотип зависит от набора генов и условий окружающей среды.

Термин «фенотип» в 1909 году предложил один из основоположников современной генетики, датский учёный Вильгельм Иогансен. Он использовал этот термин для понимания отличия наследственности организма от того, что получается в результате её реализации.

Взаимосвязь фенотипа и генотипа

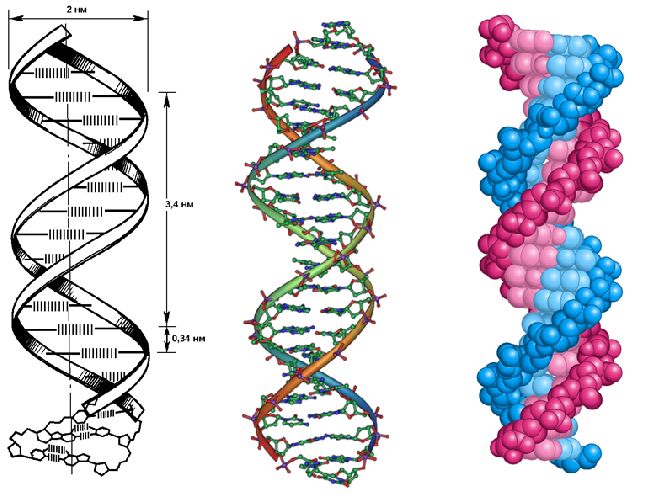

Фенотип организма определяется генотипом. Главным носителем наследственной информации у всех живых существ является ДНК — макромолекула, в которой закодированы все необходимые данные для производства молекул, клеток, тканей, органов и систем органов. По сути, ДНК — это генетический код, отвечающий за точное воспроизводство всех клеточных функций.

Унаследованные от родителей гены определяют фенотип организма. Гены — это участки ДНК, кодирующие структуры белков и определяющие различные признаки. Они могут существовать в различных формах, которые называются аллелями. Аллели располагаются на хромосомах и передаются от родителей потомству путём полового размножения.

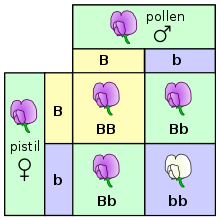

Организм наследует два аллеля для каждого гена — по одному от каждого родителя. Взаимодействие между аллелями и определяет фенотип организма:

- Если для определённого признака организм наследует два одинаковых аллеля, он называется гомозиготным по этому признаку.

- Если наследуется два разных аллеля для конкретного признака, то организм является гетерозиготным по этому признаку.

Фенотип и генотип тесно связаны друг с другом, но при этом существенно различаются между собой. Так, генотип отвечает за генетическую информацию в генном коде и может быть определен только при помощи специальных биологических исследований. Фенотип — это последствия генотипа, его физическое и видимое глазу воплощение.

О том, что такое фенотипы в биологии, можно кратко рассказать в докладе по биологии для 10 класса.

Что мы узнали?

Фенотип представляет собой совокупность внешних и внутренних признаков, свойств, черт организма, приобретённых в процессе индивидуального развития. Фенотип напрямую связан с генотипом и зависит от условий окружающей среды.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда – пройдите тест.

Пока никого нет. Будьте первым!

Оценка доклада

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 76.

А какая ваша оценка?

По какой формуле определяют число фенотипов в потомстве при расщеплении?

Для определения используется формула 2n, в которой n — количество пар аллельных генов.

Если происходит моногибридное скрещивание, «родители», наделенные отличием в одной паре признаков (Мендель экспериментировал с горошинами желтыми и зелеными), во втором поколении дают два фенотипа (21). При дигибридном скрещивании они имеют различия по двум парам признаков и, соответственно, во втором поколении производят четыре фенотипа (22).

Точно таким же образом подсчитывается количество фенотипов, получившихся во втором поколении методом тригибридного скрещивания — появится восемь фенотипов (23).

По какой формуле определяют число различных видов гамет у гетерозигот?

Это число высчитывают также по формуле (2n). Однако n в этом случае — количество пар генов в гетерозиготном состоянии. На использовании этой формулы построены задачи в ЕГЭ по биологии и внутреннем экзамене МГУ.

По какой формуле определяют число генотипов в потомстве при расщеплении?

Здесь применяется формула 3n, где n — количество пар аллельных генов. Если скрещивание моногибридное, расщепление по генотипу в F2 происходит в соотношении 1:2:1, то есть образуются три различающихся генотипа (31).

При дигибридном скрещивании возникают 9 генотипов (32), при тригибридном — 27 генотипов (33).

Хочешь сдать экзамен на отлично? Жми сюда – подготовка к ОГЭ по биологии онлайн

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Here the relation between genotype and phenotype is illustrated, using a Punnett square, for the character of petal color in pea plants. The letters B and b represent genes for color, and the pictures show the resultant phenotypes. This shows how multiple genotypes (BB and Bb) may yield the same phenotype (purple petals).

In genetics, the phenotype (from Ancient Greek φαίνω (phaínō) ‘to appear, show, shine’, and τύπος (túpos) ‘mark, type’) is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism.[1][2] The term covers the organism’s morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological properties, its behavior, and the products of behavior. An organism’s phenotype results from two basic factors: the expression of an organism’s genetic code (its genotype) and the influence of environmental factors. Both factors may interact, further affecting the phenotype. When two or more clearly different phenotypes exist in the same population of a species, the species is called polymorphic. A well-documented example of polymorphism is Labrador Retriever coloring; while the coat color depends on many genes, it is clearly seen in the environment as yellow, black, and brown. Richard Dawkins in 1978[3] and then again in his 1982 book The Extended Phenotype suggested that one can regard bird nests and other built structures such as caddisfly larva cases and beaver dams as “extended phenotypes”.

Wilhelm Johannsen proposed the genotype–phenotype distinction in 1911 to make clear the difference between an organism’s hereditary material and what that hereditary material produces.[4][5] The distinction resembles that proposed by August Weismann (1834–1914), who distinguished between germ plasm (heredity) and somatic cells (the body). More recently, in The Selfish Gene (1976), Dawkins distinguished these concepts as replicators and vehicles.

The genotype–phenotype distinction should not be confused with Francis Crick’s central dogma of molecular biology, a statement about the directionality of molecular sequential information flowing from DNA to protein, and not the reverse.

Difficulties in definition[edit]

Despite its seemingly straightforward definition, the concept of the phenotype has hidden subtleties. It may seem that anything dependent on the genotype is a phenotype, including molecules such as RNA and proteins. Most molecules and structures coded by the genetic material are not visible in the appearance of an organism, yet they are observable (for example by Western blotting) and are thus part of the phenotype; human blood groups are an example. It may seem that this goes beyond the original intentions of the concept with its focus on the (living) organism in itself. Either way, the term phenotype includes inherent traits or characteristics that are observable or traits that can be made visible by some technical procedure. A notable extension to this idea is the presence of “organic molecules” or metabolites that are generated by organisms from chemical reactions of enzymes.[citation needed]

ABO blood groups determined through a Punnett square and displaying phenotypes and genotypes

The term “phenotype” has sometimes been incorrectly used as a shorthand for the phenotypic difference between a mutant and its wild type, which (if not significant) leads to the statement that a

“mutation has no phenotype”.[6]

Another extension adds behavior to the phenotype, since behaviors are observable characteristics. Behavioral phenotypes include cognitive, personality, and behavioral patterns. Some behavioral phenotypes may characterize psychiatric disorders[7] or syndromes.[8][9]

B.betularia morpha carbonaria, the melanic form, illustrating discontinuous variation

Phenotypic variation[edit]

Phenotypic variation (due to underlying heritable genetic variation) is a fundamental prerequisite for evolution by natural selection. It is the living organism as a whole that contributes (or not) to the next generation, so natural selection affects the genetic structure of a population indirectly via the contribution of phenotypes. Without phenotypic variation, there would be no evolution by natural selection.[10]

The interaction between genotype and phenotype has often been conceptualized by the following relationship:

- genotype (G) + environment (E) → phenotype (P)

A more nuanced version of the relationship is:

- genotype (G) + environment (E) + genotype & environment interactions (GE) → phenotype (P)

Genotypes often have much flexibility in the modification and expression of phenotypes; in many organisms these phenotypes are very different under varying environmental conditions. The plant Hieracium umbellatum is found growing in two different habitats in Sweden. One habitat is rocky, sea-side cliffs, where the plants are bushy with broad leaves and expanded inflorescences; the other is among sand dunes where the plants grow prostrate with narrow leaves and compact inflorescences. These habitats alternate along the coast of Sweden and the habitat that the seeds of Hieracium umbellatum land in, determine the phenotype that grows.[11]

An example of random variation in Drosophila flies is the number of ommatidia, which may vary (randomly) between left and right eyes in a single individual as much as they do between different genotypes overall, or between clones raised in different environments.[citation needed]

The concept of phenotype can be extended to variations below the level of the gene that affect an organism’s fitness. For example, silent mutations that do not change the corresponding amino acid sequence of a gene may change the frequency of guanine-cytosine base pairs (GC content). These base pairs have a higher thermal stability (melting point) than adenine-thymine, a property that might convey, among organisms living in high-temperature environments, a selective advantage on variants enriched in GC content.[citation needed]

The extended phenotype[edit]

Richard Dawkins described a phenotype that included all effects that a gene has on its surroundings, including other organisms, as an extended phenotype, arguing that “An animal’s behavior tends to maximize the survival of the genes ‘for’ that behavior, whether or not those genes happen to be in the body of the particular animal performing it.”[3] For instance, an organism such as a beaver modifies its environment by building a beaver dam; this can be considered an expression of its genes, just as its incisor teeth are—which it uses to modify its environment. Similarly, when a bird feeds a brood parasite such as a cuckoo, it is unwittingly extending its phenotype; and when genes in an orchid affect orchid bee behavior to increase pollination, or when genes in a peacock affect the copulatory decisions of peahens, again, the phenotype is being extended. Genes are, in Dawkins’s view, selected by their phenotypic effects.[12]

Other biologists broadly agree that the extended phenotype concept is relevant, but consider that its role is largely explanatory, rather than assisting in the design of experimental tests.[13]

Genes and phenotypes[edit]

Phenotypes are determined by an interaction of genes and the environment, but the mechanism for each gene and phenotype is different. For instance, an albino phenotype may be caused by a mutation in the gene encoding tyrosinase which is a key enzyme in melanin formation. However, exposure to UV radiation can increase melanin production, hence the environment plays a role in this phenotype as well. For most complex phenotypes the precise genetic mechanism remains unknown. For instance, it is largely unclear how genes determine the shape of bones or the human ear.[citation needed]

Gene expression plays a crucial role in determining the phenotypes of organisms. The level of gene expression can affect the phenotype of an organism. For example, if a gene that codes for a particular enzyme is expressed at high levels, the organism may produce more of that enzyme and exhibit a particular trait as a result. On the other hand, if the gene is expressed at low levels, the organism may produce less of the enzyme and exhibit a different trait.[14]

Gene expression is regulated at various levels and thus each level can affect certain phenotypes, including transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation.

The patchy colors of a tortoiseshell cat are the result of different levels of expression of pigmentation genes in different areas of the skin.

Changes in the levels of gene expression can be influenced by a variety of factors, such as environmental conditions, genetic variations, and epigenetic modifications. These modifications can be influenced by environmental factors such as diet, stress, and exposure to toxins, and can have a significant impact on an individual’s phenotype. Some phenotypes may be the result of changes in gene expression due to these factors, rather than changes in genotype. An experiment involving machine learning methods utilizing gene expression measured from RNA sequencing can contain enough signal to separate individuals in the context of phenotype prediction.[15]

Phenome and phenomics[edit]

Although a phenotype is the ensemble of observable characteristics displayed by an organism, the word phenome is sometimes used to refer to a collection of traits, while the simultaneous study of such a collection is referred to as phenomics.[16][17] Phenomics is an important field of study because it can be used to figure out which genomic variants affect phenotypes which then can be used to explain things like health, disease, and evolutionary fitness.[18] Phenomics forms a large part of the Human Genome Project.[19]

Phenomics has applications in agriculture. For instance, genomic variations such as drought and heat resistance can be identified through phenomics to create more durable GMOs.[20][21]

Phenomics may be a stepping stone towards personalized medicine, particularly drug therapy.[22] Once the phenomic database has acquired more data, a person’s phenomic information can be used to select specific drugs tailored to an individual.[22]

Large-scale phenotyping and genetic screens[edit]

Large-scale genetic screens can identify the genes or mutations that affect the phenotype of an organism. Analyzing the phenotypes of mutant genes can also aid in determining gene function.[23] Most genetic screens have used microorganisms, in which genes can be easily deleted. For instance, nearly all genes have been deleted in E. coli[24] and many other bacteria, but also in several eukaryotic model organisms such as baker’s yeast[25] and fission yeast.[26] Among other discoveries, such studies have revealed lists of essential genes .

More recently, large-scale phenotypic screens have also been used in animals, e.g. to study lesser understood phenotypes such as behavior. In one screen, the role of mutations in mice were studied in areas such as learning and memory, circadian rhythmicity, vision, responses to stress and response to psychostimulants.

| Phenotypic Domain | Assay | Notes | Software Package |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circadian Rhythm | Wheel running behavior | ClockLab | |

| Learning and Memory | Fear conditioning | Video-image-based scoring of freezing | FreezeFrame |

| Preliminary Assessment | Open field activity and elevated plus maze | Video-image-based scoring of exploration | LimeLight |

| Psychostimulant response | Hyperlocomotion behavior | Video-image-based tracking of locomotion | BigBrother |

| Vision | Electroretinogram and Fundus photography | L. Pinto and colleagues |

This experiment involved the progeny of mice treated with ENU, or N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea, which is a potent mutagen that causes point mutations. The mice were phenotypically screened for alterations in the different behavioral domains in order to find the number of putative mutants (see table for details). Putative mutants are then tested for heritability in order to help determine the inheritance pattern as well as map out the mutations. Once they have been mapped out, cloned, and identified, it can be determined whether a mutation represents a new gene or not.

| Phenotypic domain | ENU Progeny screened | Putative mutants | Putative mutant lines with progeny | Confirmed mutants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General assessment | 29860 | 80 | 38 | 14 |

| Learning and memory | 23123 | 165 | 106 | 19 |

| Psychostimulant response | 20997 | 168 | 86 | 9 |

| Neuroendocrine response to stress | 13118 | 126 | 54 | 2 |

| Vision | 15582 | 108 | 60 | 6 |

These experiments showed that mutations in the rhodopsin gene affected vision and can even cause retinal degeneration in mice.[27] The same amino acid change causes human familial blindness, showing how phenotyping in animals can inform medical diagnostics and possibly therapy.

Evolutionary origin of phenotype[edit]

The RNA world is the hypothesized pre-cellular stage in the evolutionary history of life on earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated prior to the evolution of DNA and proteins.[28] The folded three-dimensional physical structure of the first RNA molecule that possessed ribozyme activity promoting replication while avoiding destruction would have been the first phenotype, and the nucleotide sequence of the first self-replicating RNA molecule would have been the original genotype.[28]

See also[edit]

- Ecotype

- Endophenotype

- Genotype-phenotype distinction

- Molecular phenotyping

- Race and genetics

References[edit]

- ^ “Phenotype adjective – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes”. Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

the set of observable characteristics of an individual resulting from the interaction of its genotype with the environment.

- ^ “Genotype versus phenotype”. Understanding Evolution. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

An organism’s genotype is the set of genes that it carries. An organism’s phenotype is all of its observable characteristics — which are influenced both by its genotype and by the environment.

- ^ a b Dawkins R (May 1978). “Replicator selection and the extended phenotype”. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 47 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1978.tb01823.x. PMID 696023.

- ^ Churchill FB (1974). “William Johannsen and the genotype concept”. Journal of the History of Biology. 7 (1): 5–30. doi:10.1007/BF00179291. PMID 11610096. S2CID 38649212.

- ^ Johannsen W (August 2014). “The genotype conception of heredity. 1911”. International Journal of Epidemiology. 43 (4): 989–1000. doi:10.1086/279202. JSTOR 2455747. PMC 4258772. PMID 24691957.

- ^ Crusio WE (May 2002). “‘My mouse has no phenotype’“. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 1 (2): 71. doi:10.1034/j.1601-183X.2002.10201.x. PMID 12884976. S2CID 35382304.

- ^ Cassidy SB, Morris CA (2002-01-01). “Behavioral phenotypes in genetic syndromes: genetic clues to human behavior”. Advances in Pediatrics. 49: 59–86. PMID 12214780.

- ^ O’Brien G, Yule W, eds. (1995). Behavioural Phenotype. Clinics in Developmental Medicine No.138. London: Mac Keith Press. ISBN 978-1-898683-06-3.

- ^ O’Brien G, ed. (2002). Behavioural Phenotypes in Clinical Practice. London: Mac Keith Press. ISBN 978-1-898683-27-8. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Lewontin RC (November 1970). “The Units of Selection” (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1: 1–18. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.01.110170.000245. JSTOR 2096764.

- ^ von Sengbusch P. “Phenotypic and Genetic Variation; Ecotypes”. Botany online: Evolution: The Modern Synthesis – Phenotypic and Genetic Variation; Ecotypes. Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ Dawkins R (1982). The Extended Phenotype. Oxford University. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-288051-2.

- ^ Hunter P (March 2009). “Extended phenotype redux. How far can the reach of genes extend in manipulating the environment of an organism?”. EMBO Reports. 10 (3): 212–215. doi:10.1038/embor.2009.18. PMC 2658563. PMID 19255576.

- ^ Oellrich, A.; Sanger Mouse Genetics Project; Smedley, D. (2014). “Linking tissues to phenotypes using gene expression profiles”. Database. 2014: bau017. doi:10.1093/database/bau017.

- ^ Nussinov, Ruth; Tsai, Chung-Jung; Jang, Hyunbum (2019). “Protein ensembles link genotype to phenotype”. PLOS Computational Biology. 15 (6): e1006648. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006648.

- ^ Mahner M, Kary M (May 1997). “What exactly are genomes, genotypes and phenotypes? And what about phenomes?”. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 186 (1): 55–63. Bibcode:1997JThBi.186…55M. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1996.0335. PMID 9176637.

- ^ Varki A, Wills C, Perlmutter D, Woodruff D, Gage F, Moore J, et al. (October 1998). “Great Ape Phenome Project?”. Science. 282 (5387): 239–240. Bibcode:1998Sci…282..239V. doi:10.1126/science.282.5387.239d. PMID 9841385. S2CID 5837659.

- ^ Houle D, Govindaraju DR, Omholt S (December 2010). “Phenomics: the next challenge”. Nature Reviews Genetics. 11 (12): 855–866. doi:10.1038/nrg2897. PMID 21085204. S2CID 14752610.

- ^ Freimer N, Sabatti C (May 2003). “The human phenome project”. Nature Genetics. 34 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1038/ng0503-15. PMID 12721547. S2CID 31510391.

- ^ Rahman H, Ramanathan V, Jagadeeshselvam N, Ramasamy S, Rajendran S, Ramachandran M, et al. (2015-01-01). “Phenomics: technologies and applications in plant and agriculture.”. In Barh D, Khan MS, Davies E (eds.). PlantOmics: The Omics of Plant Science. New Delhi: Springer. pp. 385–411. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2172-2_13. ISBN 9788132221715.

- ^ Furbank RT, Tester M (December 2011). “Phenomics – technologies to relieve the phenotyping bottleneck”. Trends in Plant Science. 16 (12): 635–644. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2011.09.005. PMID 22074787.

- ^ a b Monte AA, Brocker C, Nebert DW, Gonzalez FJ, Thompson DC, Vasiliou V (September 2014). “Improved drug therapy: triangulating phenomics with genomics and metabolomics”. Human Genomics. 8 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/s40246-014-0016-9. PMC 4445687. PMID 25181945.

- ^ Amsterdam A, Burgess S, Golling G, Chen W, Sun Z, Townsend K, et al. (October 1999). “A large-scale insertional mutagenesis screen in zebrafish”. Genes & Development. 13 (20): 2713–2724. doi:10.1101/gad.13.20.2713. PMC 317115. PMID 10541557.

- ^ Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, et al. (January 2006). “Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection”. Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (1): 2006.0008. doi:10.1038/msb4100050. PMC 1681482. PMID 16738554.

- ^ Nislow C, Wong LH, Lee AH, Giaever G (September 2016). “Functional genomics using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast deletion collections”. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2016 (9): pdb.top080945. doi:10.1101/pdb.top080945. PMID 27587784.

- ^ Kim DU, Hayles J, Kim D, Wood V, Park HO, Won M, et al. (June 2010). “Analysis of a genome-wide set of gene deletions in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe“. Nature Biotechnology. 28 (6): 617–623. doi:10.1038/nbt.1628. PMC 3962850. PMID 20473289.

- ^ Vitaterna MH, Pinto LH, Takahashi JS (April 2006). “Large-scale mutagenesis and phenotypic screens for the nervous system and behavior in mice”. Trends in Neurosciences. 29 (4): 233–240. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.02.006. PMC 3761413. PMID 16519954.

- ^ a b Michod RE (February 1983). “Population biology of the first replicators: on the origin of the genotype, phenotype and organism”. American Zoologist. 23 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1093/icb/23.1.5.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phenotypes.

Look up phenotype in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Mouse Phenome Database

- Human Phenotype Ontology

- Europhenome: Access to raw and annotated mouse phenotype data

- “Wilhelm Johannsen’s Genotype-Phenotype Distinction” by E. Peirson at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

Определение: фенотип — выраженные физические черты организма, определенные генотипом, доминирующими генами, случайной генетической вариацией и воздействием окружающей среды.

Примеры: такие черты, как цвет, высота, размер, форма и поведение.

Взаимосвязь фенотипа и генотипа

Генотип организма определяет его фенотип. Все живые организмы имеют ДНК, которая дает инструкции для производства молекул, клеток, тканей и органов. ДНК содержит генетический код, который также отвечает за направление всех клеточных функций, включая митоз, репликацию ДНК, синтез белка и перенос молекул.

Фенотип организма (физические черты и поведение) определяются их унаследованными генами. Гены представляют собой определенные участки ДНК, которые кодируют структуру белков и определяют различные признаки. Каждый ген расположен на хромосоме и может существовать в более чем одной форме. Эти различные формы называются аллелями, которые располагаются в определенных местах на определенных хромосомах. Аллели передаются от родителей к потомству через половое размножение.

Диплоидные организмы наследуют два аллеля для каждого гена; один аллель от каждого родителя. Взаимодействие между аллелями определяют фенотип организма. Если организм наследует два одинаковых аллеля для определенного признака, он гомозиготный по этому признаку. Гомозиготные особи выражают один фенотип для данного признака. Если организм наследует два разных аллеля для определенного признака, он является гетерозиготным по этому признаку. Гетерозиготные особи могут выражать более одного фенотипа для данного признака.

Черты могут быть доминирующими или рецессивными. В схемах наследования полного доминирования фенотип доминирующей черты полностью маскирует фенотип рецессивного признака. Имеются также случаи, когда отношения между разными аллелями не проявляют полного доминирования. При неполном доминировании доминирующая аллель полностью не маскирует другую аллель. Это приводит к фенотипу, который представляет собой смесь фенотипов, наблюдаемых в обеих аллелях. При кодоминировании оба аллеля полностью выражены. Это приводит к фенотипу, в котором оба признака наблюдаются независимо друг от друга.

| Вид доминирования | Черта | Аллели | Генотип | Фенотип |

| Полное доминирование | Цвет | R-красный, r-белый | Rr | красный цвет |

| Неполное доминирование | Цвет | R-красный, r-белый | Rr | розовый цвет |

| Кодоминирование | Цвет | R-красный, r-белый | Rr | красно-белый цвет |

Фенотип и генетическое разнообразие

Генетическое разнообразие может влиять на фенотипы. Оно описывает изменения генов организмов в популяции. Эти изменения могут быть результатом мутаций ДНК. Мутации являются изменениями последовательностей генов в ДНК.

Любое изменение последовательности генов может изменить фенотип, выраженный в унаследованных аллелях. Поток генов также способствует генетическому разнообразию. Когда новые организмы попадают в популяцию, вводятся новые гены. Введение новых аллелей в генофонд делает возможными новые комбинации генов и различные фенотипы.

Во время мейоза образуются различные комбинации генов. В мейозе гомологичные хромосомы случайным образом разделяются на разные клетки. Передача гена может происходить между гомологичными хромосомами через процесс пересечения. Эта рекомбинация генов может создавать новые фенотипы в популяции.

Гугломаг

Спрашивай! Не стесняйся!

Задать вопрос

Не все нашли? Используйте поиск по сайту