From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Winds are part of Earth’s atmospheric circulation.

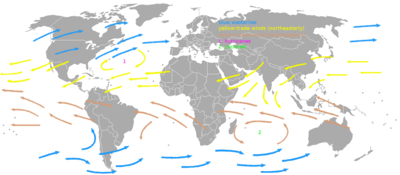

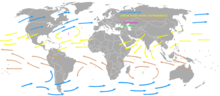

The westerlies (blue) and trade winds (yellow and brown)

Global surface wind vector flow lines colored by wind speed from June 1, 2011 to October 31, 2011.

In meteorology, prevailing wind in a region of the Earth’s surface is a surface wind that blows predominantly from a particular direction. The dominant winds are the trends in direction of wind with the highest speed over a particular point on the Earth’s surface at any given time.[1] A region’s prevailing and dominant winds are the result of global patterns of movement in the Earth’s atmosphere.[2] In general, winds are predominantly easterly at low latitudes globally. In the mid-latitudes, westerly winds are dominant, and their strength is largely determined by the polar cyclone. In areas where winds tend to be light, the sea breeze/land breeze cycle is the most important cause of the prevailing wind; in areas which have variable terrain, mountain and valley breezes dominate the wind pattern. Highly elevated surfaces can induce a thermal low, which then augments the environmental wind flow.

Wind roses are tools used to display the direction of the prevailing wind. Knowledge of the prevailing wind allows the development of prevention strategies for wind erosion of agricultural land, such as across the Great Plains. Sand dunes can orient themselves perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction in coastal and desert locations. Insects drift along with the prevailing wind, but the flight of birds is less dependent on it. Prevailing winds in mountain locations can lead to significant rainfall gradients, ranging from wet across windward-facing slopes to desert-like conditions along their lee slopes. Prevailing winds can vary due to the uneven heating of the Earth.[clarification needed]

Wind rose[edit]

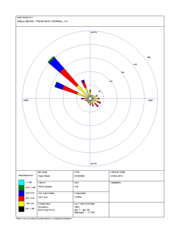

A wind rose is a graphic tool used by meteorologists to give a succinct view of how wind speed and direction are typically distributed at a particular location. Presented in a polar coordinate grid, the wind rose shows the frequency of winds blowing from particular directions. The length of each spoke around the circle is related to the proportion of the time that the wind blows from each direction. Each concentric circle represents a different proportion, increasing outwards from zero at the center. A wind rose plot may contain additional information, in that each spoke is broken down into color-coded bands that show wind speed ranges. Wind roses typically show 8 or 16 cardinal directions, such as north (N), NNE, NE, etc.,[3] although they may be subdivided into as many as 32 directions.[4]

Climatology[edit]

Trades and their impact[edit]

The trade winds (also called trades) are the prevailing pattern of easterly surface winds found in the tropics near the Earth’s equator,[5] equatorward of the subtropical ridge. These winds blow predominantly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere.[6] The trade winds act as the steering flow for tropical cyclones that form over world’s oceans, guiding their path westward.[7] Trade winds also steer African dust westward across the Atlantic Ocean into the Caribbean sea, as well as portions of southeast North America.[8]

Westerlies and their impact[edit]

The westerlies or the prevailing westerlies are the prevailing winds in the middle latitudes (i.e. between 35 and 65 degrees latitude), which blow in areas poleward of the high pressure area known as the subtropical ridge in the horse latitudes.[9][10] These prevailing winds blow from the west to the east,[11] and steer extra-tropical cyclones in this general direction. The winds are predominantly from the southwest in the Northern Hemisphere and from the northwest in the Southern Hemisphere.[6] They are strongest in the winter when the pressure is lower over the poles, such as when the polar cyclone is strongest, and weakest during the summer when the polar cyclone is weakest and when pressures are higher over the poles.[12]

Together with the trade winds, the westerlies enabled a round-trip trade route for sailing ships crossing the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, as the westerlies lead to the development of strong ocean currents in both hemispheres. The westerlies can be particularly strong, especially in the southern hemisphere, where there is less land in the middle latitudes to cause the flow pattern to amplify, which slows the winds down. The strongest westerly winds in the middle latitudes are called the Roaring Forties, between 40 and 50 degrees south latitude, within the Southern Hemisphere.[13] The westerlies play an important role in carrying the warm, equatorial waters and winds to the western coasts of continents,[14][15] especially in the southern hemisphere because of its vast oceanic expanse.

The westerlies explain why coastal Western North America tends to be wet, especially from Northern Washington to Alaska, during the winter. Differential heating from the Sun between the land which is quite cool and the ocean which is relatively warm causes areas of low pressure to develop over land. This results in moisture-rich air flowing east from the Pacific Ocean, causing frequent rainstorms and wind on the coast. This moisture continues to flow eastward until orographic lift caused by the Coast Ranges, and the Cascade, Sierra Nevada, Columbia, and Rocky Mountains causes a rain shadow effect which limits further penetration of these systems and associated rainfall eastward. This trend reverses in the summer when strong heating of the land causes high pressure and tends to block moisture-rich air from the Pacific from reaching land. This explains why most of coastal Western North America in the highest latitude experiences dry summers, despite vast rainfall in the winter.[9][10]

Polar easterlies[edit]

The polar easterlies (also known as Polar Hadley cells) are the dry, cold prevailing winds that blow from the high-pressure areas of the polar highs at the North and South Poles towards the low-pressure areas within the westerlies at high latitudes. Like trade winds and unlike the westerlies, these prevailing winds blow from the east to the west, and are often weak and irregular.[16] Due to the low sun angle, cold air builds up and subsides at the pole creating surface high-pressure areas, forcing an outflow of air toward the equator;[17] that outflow is deflected westward by the Coriolis effect.

Local considerations[edit]

Sea and land breezes[edit]

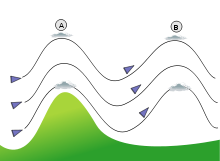

A: Sea breeze, B: Land breeze

In areas where the wind flow is light, sea breezes and land breezes are important factors in a location’s prevailing winds. The sea is warmed by the sun to a greater depth than the land due to its greater specific heat.[18] The sea therefore has a greater capacity for absorbing heat than the land, so the surface of the sea warms up more slowly than the land’s surface. As the temperature of the surface of the land rises, the land heats the air above it. The warm air is less dense and so it rises. This rising air over the land lowers the sea level pressure by about 0.2%. The cooler air above the sea, now with higher sea level pressure, flows towards the land into the lower pressure, creating a cooler breeze near the coast.

The strength of the sea breeze is directly proportional to the temperature difference between the land mass and the sea. If an off-shore wind of 8 knots (15 km/h) exists, the sea breeze is not likely to develop. At night, the land cools off more quickly than the ocean due to differences in their specific heat values, which forces the daytime sea breeze to dissipate. If the temperature onshore cools below the temperature offshore, the pressure over the water will be lower than that of the land, establishing a land breeze, as long as an onshore wind is not strong enough to oppose it.[19]

Circulation in elevated regions[edit]

Mountain wave schematic. The wind flows towards a mountain and produces a first oscillation (A). A second wave occurs further away and higher. The lenticular clouds form at the peak of the waves (B).

Over elevated surfaces, heating of the ground exceeds the heating of the surrounding air at the same altitude above sea level, creating an associated thermal low over the terrain and enhancing any lows which would have otherwise existed,[20][21] and changing the wind circulation of the region. In areas where there is rugged topography that significantly interrupts the environmental wind flow, the wind can change direction and accelerate parallel to the wind obstruction. This barrier jet can increase the low level wind by 45%.[22] In mountainous areas, local distortion of the airflow is more severe. Jagged terrain combines to produce unpredictable flow patterns and turbulence, such as rotors. Strong updrafts, downdrafts and eddies develop as the air flows over hills and down valleys. Wind direction changes due to the contour of the land. If there is a pass in the mountain range, winds will rush through the pass with considerable speed due to the Bernoulli principle that describes an inverse relationship between speed and pressure. The airflow can remain turbulent and erratic for some distance downwind into the flatter countryside. These conditions are dangerous to ascending and descending airplanes.[23]

Daytime heating and nighttime cooling of the hilly slopes lead to day to night variations in the airflow, similar to the relationship between sea breeze and land breeze. At night, the sides of the hills cool through radiation of the heat. The air along the hills becomes cooler and denser, blowing down into the valley, drawn by gravity. This is known a mountain breeze. If the slopes are covered with ice and snow, the mountain breeze will blow during the day, carrying the cold dense air into the warmer, barren valleys. The slopes of hills not covered by snow will be warmed during the day. The air that comes in contact with the warmed slopes becomes warmer and less dense and flows uphill. This is known as an anabatic wind or valley breeze.[24]

Effect on precipitation[edit]

Orographic precipitation occurs on the windward side of mountains and is caused by the rising air motion of a large-scale flow of moist air across the mountain ridge, resulting in adiabatic cooling and condensation. In mountainous parts of the world subjected to consistent winds (for example, the trade winds), a more moist climate usually prevails on the windward side of a mountain than on the leeward or downwind side. Moisture is removed by orographic lift, leaving drier air (see foehn wind) on the descending and generally warming, leeward side where a rain shadow is observed.[25]

In South America, the Andes mountain range blocks Pacific moisture that arrives in that continent, resulting in a desertlike climate just downwind across western Argentina.[26] The Sierra Nevada range creates the same effect in North America forming the Great Basin and Mojave Deserts.[27][28]

Effect on nature[edit]

Insects are swept along by the prevailing winds, while birds follow their own course.[29] As such, fine line patterns within weather radar imagery, associated with converging winds, are dominated by insect returns.[30] In the Great Plains, wind erosion of agricultural land is a significant problem, and is mainly driven by the prevailing wind. Because of this, wind barrier strips have been developed to minimize this type of erosion. The strips can be in the form of soil ridges, crop strips, crops rows, or trees which act as wind breaks. They are oriented perpendicular to the wind in order to be most effective.[31] In regions with minimal vegetation, such as coastal and desert areas, transverse sand dunes orient themselves perpendicular to the prevailing wind direction, while longitudinal dunes orient themselves parallel to the prevailing winds.[32]

See also[edit]

- Trade winds

- Wind speed

- Atmospheric circulation

- Winds in the age of sail

References[edit]

- ^ “Where does Wind Come From? (Video)”. www.mometrix.com. 2021-07-19. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ^ URS (2008). Section 3.2 Climate conditions (in Spanish). Estudio de Impacto Ambiental Subterráneo de Gas Natural Castor. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Wind rose. Archived 2012-03-15 at the Wayback Machine American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-25.

- ^ Jan Curtis (2007). Wind Rose Data. Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). “trade winds”. Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b Ralph Stockman Tarr; Frank Morton McMurry; Almon Ernest Parkins (1909). Advanced geography. Macmillan. pp. 246–.

- ^ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2006). 3.3 JTWC Forecasting Philosophies. United States Navy. Retrieved on 2007-02-11.

- ^ Science Daily (1999-07-14). African Dust Called A Major Factor Affecting Southeast U.S. Air Quality. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- ^ a b Glossary of Meteorology (2009). “Westerlies”. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ a b Sue Ferguson (2001-09-07). “Climatology of the Interior Columbia River Basin” (PDF). Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Westerlies. Archived 2010-06-22 at the Wayback Machine American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ^ Halldór Björnsson (2005). Global circulation. Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine Veðurstofu Íslands. Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

- ^ Walker, Stuart (1998). The sailor’s wind. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 91. ISBN 9780393045550.

Roaring Forties Shrieking Sixties westerlies.

- ^ Barbie Bischof; Arthur J. Mariano; Edward H. Ryan (2003). “The North Atlantic Drift Current”. The National Oceanographic Partnership Program. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ Erik A. Rasmussen; John Turner (2003). Polar Lows. Cambridge University Press. p. 68.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Polar easterlies. Archived 2012-07-12 at the Wayback Machine American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ^ Michael E. Ritter (2008). The Physical Environment: Global scale circulation. Archived 2009-05-06 at the Wayback Machine University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ^ Dr. Steve Ackerman (1995). Sea and Land Breezes. University of Wisconsin. Retrieved on 2006-10-24.

- ^ JetStream: An Online School For Weather (2008). The Sea Breeze. Archived 2006-09-23 at the Wayback Machine National Weather Service. Retrieved on 2006-10-24.

- ^ National Weather Service Office in Tucson, Arizona (2008). What is a monsoon? National Weather Service Western Region Headquarters. Retrieved on 2009-03-08.

- ^ Hahn, Douglas G.; Manabe, Syukuro (1975). “The Role of Mountains in the South Asian Monsoon Circulation”. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 32 (8): 1515–1541. Bibcode:1975JAtS…32.1515H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1975)032<1515:TROMIT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Doyle, J. D. (1997). “The influence of mesoscale orography on a coastal jet and rainband”. Monthly Weather Review. 125 (7): 1465–1488. Bibcode:1997MWRv..125.1465D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1997)125<1465:TIOMOO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0027-0644.

- ^ National Center for Atmospheric Research (2006). T-REX: Catching the Sierra’s waves and rotors Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2006-10-21.

- ^ ALLSTAR Network (2009). Flight Environment: Prevailing winds. Florida International University. Retrieved on 2009-04-25.

- ^ Dr. Michael Pidwirny (2008). CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes. Physical Geography. Retrieved on 2009-01-01.

- ^ Paul E. Lydolph (1985). The Climate of the Earth. Rowman & Littlefield, p. 333. ISBN 978-0-86598-119-5. Retrieved on 2009-01-02.

- ^ Michael A. Mares (1999). Encyclopedia of Deserts. University of Oklahoma Press, p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8061-3146-7. Retrieved on 2009-01-02.

- ^ Adam Ganson (2003). Geology of Death Valley. Indiana University. Retrieved on 2009-02-07.

- ^ Diana Yates (2008). Birds migrate together at night in dispersed flocks, new study indicates. University of Illinois at Urbana – Champaign. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ Bart Geerts and Dave Leon (2003). P5A.6 Fine-Scale Vertical Structure of a Cold Front As Revealed By Airborne 95 GHZ Radar. University of Wyoming. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ W. S. Chepil, F. H. Siddoway and D. V. Armbrust (1964). In the Great Plains: Prevailing Wind Erosion Direction. Archived 2010-06-25 at the Wayback Machine Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, March–April 1964, p. 67. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ Ronald Greeley, James D. Iversen (1987). Wind as a geological process on Earth, Mars, Venus and Titan. CUP Archive, pp. 158–162. ISBN 978-0-521-35962-7. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

Карта пассатов и западных ветров умеренного пояса

Преимущественные ветры — ветры, которые дуют преимущественно в одном направлении над конкретной точкой земной поверхности. Являются частью глобальной картины циркуляции воздуха в атмосфере Земли, включая пассаты, муссоны, западные ветры умеренного пояса и восточные ветры полярных районов[1]. В районах, где глобальные ветры слабы, преимущественные ветры определяются направлениями бриза и другими локальными факторами. Кроме того, глобальные ветры могут отклоняться от типовых направлений в зависимости от наличия препятствий.

Для определения направления преимущественного ветра используется роза ветров. Знание направления ветра позволяет разрабатывать план защиты сельхозугодий от эрозии почв.

Песчаные дюны в прибрежных и пустынных местах могут ориентироваться вдоль либо перпендикулярно направлению постоянного ветра. Насекомые дрейфуют по ветру, а птицы летают независимо от преобладающего ветра. Преобладающие ветры в гористых местностях могут привести к значительной разнице в осадках на наветренных (влажных) и подветренных (сухих) склонах.

Определение на месте[править | править код]

Роза ветров Международного аэропорта Фресно-Йосемити, Калифорния, 1961—1990 годы.

Основная статья: Роза ветров

Роза ветров — графическое изображение частоты ветров каждого направления в данной местности, построенное в виде гистограммы в полярных координатах. Каждая черточка в кругу показывает частоту ветров в конкретном направлении, а каждый концентрический круг соответствует определенной частоте. Роза ветров может содержать и дополнительную информацию, например, каждая черточка может быть окрашена в различные цвета, соответствующие некоторому диапазона скорости ветра. Розы ветров чаще имеют 8 или 16 черточек, соответствующих основным направлениям, то есть северу (N), северо-западу (NW), западу (W) и т. д., или N, NNW, NW, NWW, W и т. д .[2], иногда число черточек составляет 32[3]. Если частота ветра определенного направления или диапазона направлений значительно превышает частоту ветра в других направлениях, говорят о наличии преимущественных ветров в этой местности.

Климатология[править | править код]

Влияние преобладающего ветра на хвойное дерево в западной Турции.

Пассаты и их влияние[править | править код]

Основная статья: пассаты

Пассаты (англ. trade-winds или trades, «торговые ветры») — ветры восточного направления, дующие круглый год между тропиками[4], отделяясь друг от друга безветренной полосой. Эти ветры дуют преимущественно в северо-восточном направлении в северном полушарии и в юго-восточном в южном[5]. Пассаты выступают в качестве руководящего потока для тропических циклонов, которые формируются над океанами, направляя их путь на запад[6]. Также они переносят африканскую пыль на запад через Атлантический океан в Карибское море и частично на юго-восток Северной Америки[7].

Западные ветры умеренного пояса и их влияние[править | править код]

Западные ветры умеренного пояса дуют в средних широтах между 35 и 65 градусами северной или южной широты, в направлении с запада на восток к северу от области высокого давления[8][9], направляя внетропические циклоны в соответствующем направлении. Причем сильнее дуют в зимнее время, когда давление над полюсами ниже, и слабее летом.[10]

Западные ветры приводят к развитию сильных океанских течений в обоих полушариях, но особенно мощных в южном полушарии, где в средних широтах меньше суши. Западные ветры играют важную роль в переносе теплых экваториальных вод и воздушных масс на западные побережья континентов[11][12], особенно в южном полушарии из-за преобладания океанического пространства.

Восточные ветры полярных районов[править | править код]

Основная статья: Восточные ветры полярных районов

Восточные ветры полярных районов — сухие холодные ветры, дующие из полярных областей высокого давления в более низкие широты. В отличие от пассатов и западных ветров, они дуют с востока на запад и зачастую являются слабыми и нерегулярными[13]. Из-за низкого угла падения солнечных лучей холодный воздух накапливается и оседает, создавая области высокого давления, выталкивая воздух к экватору[14]; этот поток отклоняется на запад благодаря эффекту Кориолиса.

Влияние местных особенностей[править | править код]

Морской бриз[править | править код]

Основная статья: Бриз

В районах, где нет мощных воздушных течений, важным фактором в формировании преобладающих ветров является бриз. Днем море прогревается на бо’льшую глубину, чем суша, поскольку вода имеет бо’льшую удельную теплоемкость[15], но при этом гораздо медленнее, чем поверхность земли. Температура поверхности земли поднимается, и нагревается воздух над ней. Теплый воздух менее плотный и поэтому он поднимается вверх. Этот подъём снижает давление воздуха над землей примерно на 0,2 % (на высоте уровня моря). Холодный воздух над морем, имеющий более высокое давление, течет по направлению к земле с более низким давлением, создавая прохладный бриз вблизи побережья.

Сила морского бриза прямо пропорциональна разности температур суши и моря. Ночью земля остывает быстрее, чем океан — также из-за различий в их теплоемкости. Как только температура суши опускается ниже температуры моря, возникает ночной бриз — дующий с суши на море[16].

Ветры в гористых районах[править | править код]

В местностях с неравномерным рельефом может значительно изменяться естественное направление ветра. В горных районах искажения воздушного потока более серьёзные. Над холмами и долинами возникают сильные восходящие и нисходящие потоки, вихри. Если в горной цепи есть узкий проход, ветер устремится через него с возросшей скоростью, по принципу Бернулли. На некотором удалении от нисходящего воздушного течения воздух может оставаться неустойчивым и турбулентным, что представляет особую опасность для взлетающих и садящихся самолетов[17].

В результате нагрева и охлаждения холмистых склонов в течение суток могут появляться потоки воздуха, похожие морской бриз. Ночью склоны холмов охлаждаются. Воздух над ними становится холоднее, тяжелее и опускается в долину под действием силы тяжести. Такой ветер называется горным бризом или стоковым ветром. Если склоны покрыты снегом и льдом, стоковый ветер будет дуть в низину в течение всего дня. Склоны холмов, не покрытые снегом, будут нагреваться в течение дня. Тогда образуются восходящие потоки воздуха из более холодной долины.

Влияние на осадки[править | править код]

Схема орографических осадков

Преобладающие ветры оказывают значительное влияние на распределение осадков вблизи препятствий, таких как горы, которые должен преодолевать ветер. На наветренной стороне гор выпадают орографические осадки, обусловленные подъёмом воздуха вверх и его адиабатическим охлаждением, в результате чего влага, содержащаяся в нём, конденсируется и выпадает в виде осадков. Напротив, на подветренной стороне гор воздуха опускается вниз и нагревается, уменьшая таким образом относительную влажность и вероятность осадков, образуя дождевую тень[18]. В результате, в горных районах с преобладающими ветрами наветренную сторону гор обычно характеризуется влажным климатом, а подветренную — засушливым.

Например, в Андах бо’льшая часть осадков выпадает на наветренном тихоокеанском склоне, в то время как на континенте, в Патагонии, образуется пустынный, засушливый климат[19].

Влияние на природу[править | править код]

См. также: дюна, эрозия и насекомые

Преимущественные ветры оказывают влияние и на живую природу, например, они переносят насекомых, тогда как птицы способны бороться с ветром и придерживаться своего курса[20]. В результате, преобладающие ветры определяют направления миграции насекомых[21]. Другим воздействием ветра на природу является эрозия. Для защиты от такой эрозии часто строят барьеры от ветра в виде насыпей, лесозащитных полос и других препятствий, ориентированных, для увеличения эффективности, перпендикулярно направлению преобладающих ветров[22]. Преобладающие ветры также приводят к образованию дюн в пустынных районах, которые могут ориентироваться как перпендикулярно, так и параллельно направлению ветров[23].

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ URS (2008). Section 3.2 Climate conditions (in Spanish). Архивная копия от 1 января 2014 на Wayback Machine Estudio de Impacto Ambiental Subterráneo de Gas Natural Castor. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Wind rose. Архивная копия от 15 марта 2012 на Wayback Machine American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Jan Curtis (2007). Wind Rose Data. Архивная копия от 9 октября 2010 на Wayback Machine Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology. trade winds (недоступная ссылка — история). Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society (2009). Дата обращения: 8 сентября 2008. Архивировано 22 августа 2011 года.

- ↑ Ralph Stockman Tarr and Frank Morton McMurry (1909).Advanced geography. Архивная копия от 2 января 2014 на Wayback Machine W.W. Shannon, State Printing, pp. 246. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2006). 3.3 JTWC Forecasting Philosophies. Архивная копия от 29 ноября 2007 на Wayback Machine United States Navy. Retrieved on 2007-02-11.

- ↑ Science Daily (1999-07-14). African Dust Called A Major Factor Affecting Southeast U.S. Air Quality. Архивная копия от 7 июля 2017 на Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology. Westerlies (недоступная ссылка — история). American Meteorological Society (2009). Дата обращения: 15 апреля 2009. Архивировано 22 августа 2011 года.

- ↑ Sue Ferguson. Climatology of the Interior Columbia River Basin (недоступная ссылка — история). Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project (7 сентября 2001). Дата обращения: 12 сентября 2009. Архивировано 22 августа 2011 года.

- ↑ Halldór Björnsson (2005). Global circulation. Архивировано 22 июня 2012 года. Veðurstofu Íslands. Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Barbie Bischof, Arthur J. Mariano, Edward H. Ryan. The North Atlantic Drift Current. The National Oceanographic Partnership Program (2003). Дата обращения: 10 сентября 2008. Архивировано 22 августа 2011 года.

- ↑ Erik A. Rasmussen, John Turner. Polar Lows (неопр.). — Cambridge University Press, 2003. — С. 68.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Polar easterlies. Архивировано 22 июня 2012 года. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Michael E. Ritter (2008). The Physical Environment: Global scale circulation. Архивировано 22 июня 2012 года. University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Dr. Steve Ackerman (1995). Sea and Land Breezes. Архивная копия от 13 февраля 2020 на Wayback Machine University of Wisconsin. Retrieved on 2006-10-24.

- ↑ JetStream: An Online School For Weather (2008). The Sea Breeze. Архивная копия от 23 сентября 2006 на Wayback Machine National Weather Service. Retrieved on 2006-10-24.

- ↑ National Center for Atmospheric Research (2006). T-REX: Catching the Sierra’s waves and rotors Архивировано 22 июня 2012 года. Retrieved on 2006-10-21.

- ↑ Dr. Michael Pidwirny (2008). CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes. Архивная копия от 20 декабря 2008 на Wayback Machine Physical Geography. Retrieved on 2009-01-01.

- ↑ Paul E. Lydolph (1985). The Climate of the Earth. Архивная копия от 17 марта 2017 на Wayback Machine Rowman & Littlefield, p. 333. ISBN 978-0-86598-119-5. Retrieved on 2009-01-02.

- ↑ Diana Yates (2008). Birds migrate together at night in dispersed flocks, new study indicates. Архивная копия от 18 августа 2015 на Wayback Machine University of Illinois at Urbana — Champaign. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Bart Geerts and Dave Leon (2003). P5A.6 Fine-Scale Vertical Structure of a Cold Front As Revealed By Airborne 95 GHZ Radar. Архивная копия от 7 октября 2008 на Wayback Machine University of Wyoming. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ↑ W. S. Chepil, F. H. Siddoway and D. V. Armbrust (1964). In the Great Plains: Prevailing Wind Erosion Direction. Архивная копия от 25 июня 2010 на Wayback Machine Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, March-April 1964, p. 67. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Ronald Greeley, James D. Iversen (1987). Wind as a geological process on Earth, Mars, Venus and Titan. Архивная копия от 25 марта 2017 на Wayback Machine CUP Archive, pp. 158—162. ISBN 978-0-521-35962-7. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

Внимание: Данные взяты из СНиП 2.01.01-82 “Строительная климатология и геофизика”. Названия населенных пунктов и регионов могут не совпадать с текущими именами. Будьте внимательны!

Роза ветров («Роза компаса»). Определение

Векторная диаграмма, характеризующая в метеорологии и климатологии, режим ветра в данном месте по многолетним наблюдениям и выглядит как многоугольник, у которого длины лучей, расходящихся от центра диаграммы в разных направлениях, пропорциональны повторяемости ветров этих направлений. Роза ветров, построенная по реальным данным наблюдений, позволяет по длине лучей построенного многоугольника выявить направление преобладающего ветра, со стороны которого чаще всего приходит воздушный поток в данную местность.

Скачать розу ветров Москвы в формате автокад (dwg).

На нашем сайте вы сможете найти и скачать розы ветров для таких крупных городов России, как: Москва, Санкт-Петербург, Новосибирск, Екатеринбург, Нижний Новгород, Казань, Самара, Омск, Челябинск, Ростов-на-Дону, Уфа, Волгоград, Красноярск, Пермь, Воронеж, Саратов, Краснодар, Тольятти, Тюмень, Ижевск, Барнаул, Ульяновск, Иркутск, Владивосток, Ярославль, Хабаровск, Махачкала, Оренбург, Новокузнецк, Томск, Кемерово, Рязань, Астрахань, Пенза, Набережные Челны, Липецк.

| Ветры |

Пассаты |

Муссоны |

Западные ветры |

Восточные ветры |

|

Область распространения |

Образуются в области высокого давления тропического пояса и дуют от тропиков к экватору. |

Возникают из-за неравномерности нагревания суши и океана, вследствие чего возникает разность в атмосферном давлении. |

Образуются в области высокого давления тропического пояса и дуют в области умеренных широт. |

Образуются в областях высокого давления арктического и антарктического поясов и дуют к умеренным широтам. |

|

Отличительные черты господствующих ветров |

В Северном полушарии дуют с северо-востока на юго-запад. В Южном полушарии дуют с юго-востока на северо-запад. |

Меняют направление два раза в год. Зимой дуют с суши на море, а летом – с моря на сушу. |

В Северном полушарии дуют с юго-запада на северо-восток, В Южном – с северо-запада на юго-восток. Усиливаются зимой. |

В Северном полушарии дуют северо-восточные ветры, в Южном – юго-восточные. |

Опубликовано 12 января, 2019

Как с помощью розы ветров определить преобладающее направление ветра и для чего это нужно?

Профи

(533),

на голосовании

6 лет назад

Голосование за лучший ответ

Виктор Пронин

Ученик

(85)

6 лет назад

Направление определяет флюгер, а не роза. Флюгер должен быть сбалансирован и стабилизирован (см. книгу Бунимович, Катера и яхты), преобладание надо год журналить, нужно, чтобы знать, с какой стороны забор подпирать.

Арина Коваленко

Ученик

(196)

6 лет назад

Результаты наблюдений за направлением ветра можно изобразить с помощью особого графика, который называется роза ветров. Нужно начертить линии, показывающие основные и промежуточные румбы. Получается такая восьмилучевая звезда. На каждой линии, начиная от центра, наносятся деления по 1 см или по 0,5 см. Затем, считая, что одно деление — это один день, отмечаем на каждой линии такое количество делений, сколько дней в месяце ветер имел именно это направление. Когда по всем румбам отложено число соответствующих дней, можно соединить концы отрезков. Получившаяся фигура — роза ветров для данного места за необходимый промежуток времени.

Подробнее на: https://resheba.com/gdz/geografija/6-klass/domogackih/18

Марина Владимировна

Знаток

(295)

4 года назад

Результаты наблюдений за направлением ветра можно изобразить с помощью особого графика, который называется роза ветров. Нужно начертить линии, показывающие основные и промежуточные румбы. Получается такая восьмилучевая звезда. На каждой линии, начиная от центра, наносятся деления по 1 см или по 0,5 см. Затем, считая, что одно деление — это один день, отмечаем на каждой линии такое количество делений, сколько дней в месяце ветер имел именно это направление. Когда по всем румбам отложено число соответствующих дней, можно соединить концы отрезков. Получившаяся фигура — роза ветров для данного места за необходимый промежуток времени.

Камиль Шаймарданов

Ученик

(165)

4 года назад

Результаты наблюдений за направлением ветра можно изобразить с помощью особого графика, который называется роза ветров. Нужно начертить линии, показывающие основные и промежуточные румбы. Получается такая восьмилучевая звезда. На каждой линии, начиная от центра, наносятся деления по 1 см или по 0,5 см. Затем, считая, что одно деление — это один день, отмечаем на каждой линии такое количество делений, сколько дней в месяце ветер имел именно это направление. Когда по всем румбам отложено число соответствующих дней, можно соединить концы отрезков. Получившаяся фигура — роза ветров для данного места за необходимый промежуток времени.