Калифорний-252 – так называется самый дорогой металл в мире. В 2023 году на планете его запасы составляют не более 8 г. За год производство металла не превышает 40 мг.

Столь кропотливую и дорогостоящую работу выполняли заводы двух стран мира – РФ и США. Но в 2023 году американское предприятие по производству Калифорния-252 прекратило свое существование.

Почему Калифорний-252 такой дорогой?

Стоимость металлов зависит от двух факторов: количества запасов и сложности их добычи.

По всем показателям Калифорний-252 является самым редким и трудно добываемым металлом на планете. В естественном виде его найти нельзя. Но можно добыть из плутония или кюрия.

Справка: плутоний и кюрий – тоже редкие и дорогие металлы. В РФ запасов плутония не более 900 т. Стоимость 1 г вещества –300 000 рублей. За кюрий придется заплатить еще больше – 16 500 000 рублей. Металл преимущественно добывают из плутония.

Стоимость 1 г Калифорния-252 еще выше. В рублях она составляет 487 500 000 рублей, что делает его самым дорогим металлом РФ, добываемым на территории страны.

Особенности добычи Калифорния-252 в РФ

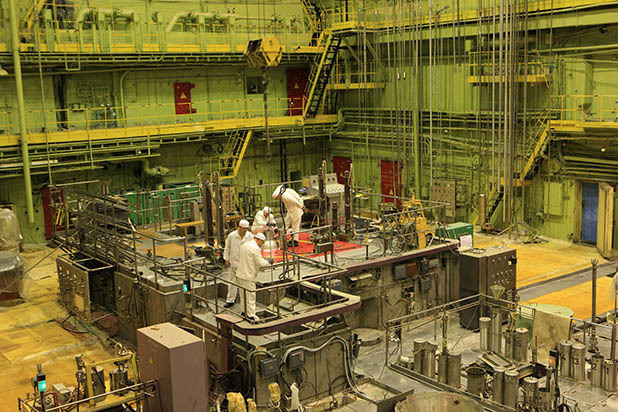

В РФ редкий и дорогостоящий Калифорний-252 добывается только в Димитровграде – одном из ядерных «сердец» страны. Там, в Ульяновской области, сосредоточен один из крупнейших со времен СССР НИИ по ядерной промышленности.

Справка: НИИАР в Димитровграде – градообразующий объект. На территории предприятия работает свыше 4 тыс. сотрудников при условии, что в самом городке проживает не более 100 тыс. Ранее в Институте изучали и практиковали работу ядерных реакторов. Теперь в здешних лабораториях исследуют возможности использования радиации в медицине и разрабатывают стратегии по улучшению экологии на зараженных радиациях территориях.

На базе НИИАР действуют 6 ядерных реакторов. Но они применяются только в научных целях. Основное назначение – создание материалов, которые нельзя встретить в естественных условиях.

Например, редкого металла Калифорний-252. Из плутония его добывают примерно 8 лет, из кюрия 1,5 года. Еще 1-2 года уходят на добычу чистого металла из полученной после обработки плутония или кюрия смеси.

Ценность Калифорния-252

Ядерные реакторы в НИИАР позволяют отечественным ученым получать редчайшие вещества, материалы, элементы. Калифорний-252 – один из них. Он уникален благодаря ядерному потенциалу, заключенному в редком металле.

Для сравнения: в 1 грамме Калифорния-252 столько же ядерной мощи, что и в энергии, производимой современным ядерным реактором.

Но на этом важность металла для науки и человечества не заканчивается. Можно применять Калифорний-252 как рентген, способный улавливать даже миллиметровые пробоины в авиационной технике.

Его нейроны могут бороться с раковыми клетками, вылечивая ранее безнадежные заболевания.

В добывающей отрасли Калифорний-252 полезен тем, что позволяет точно определить запасы редких природных элементов.

Как РФ удалось обойти США в создании Калифорния-252

Производство такого редкого металла, как Калифорний-252, свидетельствует о высоком научном потенциале любой страны.

Но в силу редкости, дороговизны и трудности добычи до 2023 года лишь 2 страны в мире могли позволить себе его получение.

Первая – это РФ, где Калифорний-252 создавался в НИИАР Димитровграда. Вторая – США.

Создание редчайшего металла осуществлялось в Окриджской национальной лаборатории. Недавно стало известно, что в этой лаборатории США произошло возгорание.

Американцы тут же поспешили уверить СМИ, что ничего страшного не случилось, и что пожар был мгновенно ликвидирован.

Но очевидцы случившегося заявляют, что важнейшие офисы лаборатории исчезли с лица земли. И один из них, возможно, был связан с производством самого дорого металла на планете.

США не подтвердило версию о том, что лаборатория по производству Калифорния-252 сгорела. Это стало бы доказательством, что единственным местом добычи металла осталась НИИАР в РФ.

Зная опыт американцев, никогда не признающих свои промахи, можно с уверенностью сказать – в 2023 году России вновь удалось обойти США, и теперь уже – в одной из важнейших отраслей научно-исследовательской среды.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Если понравилась статья – подпишитесь на канал и поставьте лайк, чтобы не пропустить следующие публикации!

Более половины элементов в таблице Менделеева являются металлами. Из них сделаны многие вещи, которые мы используем ежедневно – ключи от квартиры, некоторые виды посуды, бытовая техника и электроника. Некоторые металлы распространены и стоят относительно недорого, а есть среди них высоко востребованные, но добываемые в небольших количествах. Например, по данным Центробанка 1 грамм палладия оценивается выше 4 500 рублей (на момент публикации).

Какой металл является самым дорогим на планете и когда его открыли?

Среди всех металлов есть настоящий рекордсмен, как по цене, так и по трудности добычи. Им является калифорний-252. На нашей планете имеется не более 10 грамм этого металла в чистом виде! Калифорний-252 был открыт и впервые получен в 50-х годах прошлого века, когда между США и СССР шла гонка технологий, а своим названием он обязан американским учёным.

Как получают Калифорний-252?

Металл получают путём бомбардировки кюрия и плутония потоками нейтронов. Процесс протекает в ядерном реакторе, а за время облучения происходят сложные ядерные трансформации элементов (плутоний-америций-кюрий-берклий-калифорний). Чтобы получить всего 1 грамм калифорния-252 нужно потратить около 10 килограммов радиоактивного плутония.

После завершения ядерных реакций, калифорний-252 получается не в чистом виде. Его сложные оксиды и соли необходимо восстановить до металла. Период полураспада элемента составляет чуть больше 2 лет. Это значит, что через этот срок останется лишь половина активных ядер.

Сколько стоит самый дорогой металл и где его производят?

Вышеописанный процесс невероятно сложно реализовать, а потому металл очень дорогой. Цена всего 1 грамма этого металла может доходить до 30 миллионов долларов! Получают калифорний-252 всего в двух местах на планете: в США (Окриджская национальная лаборатория) и в России (Димитровград, Научно-исследовательский институт атомных реакторов).

Где используют Калифорний-252?

Высокая цена калифорния-252 оправдана его уникальными свойствами. Изотоп спонтанно испускает мощнейший поток нейтронов. Это сопоставимо с таким же количеством излучения урана, который находится в рабочем реакторе. Металл может быть использован для первичного запуска ядерных реакторов, для исследования свойств материи и для широкого спектра физических исследований.

Калифорний-252 может быть применён для лечения онкологии. Мельчайший образец металла, испускающий медленные нейтроны, способен разрушать поражённые клетки. Также нейтронный анализ используют в неразрушающей диагностике предметов старины, для определения их возраста и подлинности.

Если статья была интересна, пожалуйста, поддержите лайком!

Подписывайтесь на канал, чтобы не пропустить новые материалы.

Текущая версия страницы пока не проверялась опытными участниками и может значительно отличаться от версии, проверенной 9 октября 2022 года; проверки требуют 10 правок.

| Калифорний | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ← Берклий | Эйнштейний → | |||

|

|||

| Внешний вид простого вещества | |||

| Радиоактивный металл серебристо-белого цвета | |||

|

|||

| Свойства атома | |||

| Название, символ, номер | Калифо́рний / Californium (Cf), 98 | ||

| Атомная масса (молярная масса) |

251,0796 а. е. м. (г/моль) | ||

| Электронная конфигурация | [Rn] 5f10 7s2 | ||

| Радиус атома | 295 пм | ||

| Химические свойства | |||

| Электроотрицательность | 1,3 (шкала Полинга) | ||

| Электродный потенциал |

Cf ← Cf3+: −1,93 В Cf ← Cf2+: −2,1 В |

||

| Степени окисления | +2, +3, +4 | ||

| Термодинамические свойства простого вещества | |||

| Плотность (при н. у.) | 15,1 г/см³ | ||

| Температура плавления | 1173,15 К (900[1] °С, 1652 °F) | ||

| Температура кипения | оценочно 1743 K (1470 °C) | ||

| Молярная теплоёмкость | 29[2] Дж/(K·моль) | ||

| Кристаллическая решётка простого вещества | |||

| Структура решётки | гексагональная | ||

| Параметры решётки | a = 3,38, c = 11,03[3] | ||

| Отношение c/a | 3,26 | ||

| Номер CAS | 7440-71-3 |

Калифо́рний — искусственный радиоактивный химический элемент, актиноид, обозначаемый Cf, имеющий атомный номер 98 в периодической системе Менделеева. Известны радиоизотопы с массовыми числами 237—256. Стабильных изотопов не имеет[4].

Данный элемент был впервые синтезирован в 1950 году в Национальной лаборатории им. Лоуренса в Беркли (тогда Лаборатория радиации Калифорнийского университета) путём бомбардировки кюрия альфа-частицами (ионами гелия-4). Актиноид, шестой трансурановый элемент, который был когда-либо синтезирован, и имеет вторую по величине атомную массу среди всех элементов, которые были произведены в таких количествах, чтобы их можно было разглядеть невооружённым глазом (после эйнштейния). Элемент был назван в честь штата Калифорния и университета из этого штата.

История[править | править код]

Получен искусственно в 1950 году американскими физиками С. Томпсоном, К. Стритом, А. Гиорсо и Г. Сиборгом в Калифорнийском университете в Беркли при облучении 242Cm ускоренными α-частицами[4].

Первые твёрдые соединения калифорния — 249Cf2O3 и 249CfOCl получены в 1958 году.

Происхождение названия[править | править код]

Назван в честь Калифорнийского университета в Беркли, где и был получен. Как писали авторы, этим названием они хотели указать, что открыть новый элемент им было так же трудно, как век назад пионерам Америки достичь Калифорнии.

Получение[править | править код]

Калифорний производят в двух местах: НИИАР в Димитровграде (Россия), Ок-Риджской национальной лаборатории в США.

Для производства одного грамма калифорния плутоний или кюрий подвергают длительному нейтронному облучению в ядерном реакторе, от 8 месяцев до 1,5 лет. Затем из получившихся продуктов облучения химическим путём выделяют калифорний.

Металлический калифорний получают путём восстановления фторида калифорния CfF3 литием:

или оксида калифорния Cf2O3 кальцием:

.

От других актиноидов калифорний отделяют экстракционными и хроматографическими методами.

Физические и химические свойства[править | править код]

Калифорний представляет собой серебристо-белый металл[5] с температурой плавления 900 ± 30° C и предполагаемой температурой кипения 1470 °C[6]. Чистый металл податлив и легко режется ножом. Металлический калифорний начинает испаряться при температуре выше 300 °C под вакуумом[7]. Образует сплавы с лантаноидными металлами, но о них мало что известно[7].

Калифорний — чрезвычайно летучий металл. Существует в двух полиморфных модификациях. Ниже 600 °C устойчива α-модификация с гексагональной решёткой (параметры а = 0,339 нм, с = 1,101 нм), выше 600 °C — β-модификация с кубической гранецентрированной решёткой. Температура плавления металла 900 °C, температура кипения 1470 °C.[6].

По химическим свойствам калифорний подобен остальным актиноидам[4]. Синтезированы галогениды калифорния CfX3 и оксигалогениды CfOX. Для получения диоксида калифорния CfO2 оксид Cf2O3 окисляют при нагревании кислородом под давлением 10 МПа. В растворах Cf4+ получают, действуя на соединения Cf3+ сильными окислителями. Синтезирован твёрдый дииодид калифорния CfI2. Из водных растворов Cf3+ может быть восстановлен до Cf2+ электрохимическим способом.

Изотопы[править | править код]

Известно 17 изотопов калифорния, наиболее стабильными из которых являются 251Cf с периодом полураспада T1/2 = 900 лет, 249Cf (T1/2 = 351 год), 250Cf (T1/2 = 13,08 года) и 252Cf (T1/2 = 2,645 года)[8]. Последний изотоп имеет высокий коэффициент размножения нейтронов (выше 3) и критическую массу около 5 кг[9] (для металлического шара). Грамм 252Cf испускает около 3⋅1012 нейтронов в секунду[10].

Применение[править | править код]

Наибольшее применение нашёл изотоп 252Cf. Он используется как мощный источник нейтронов в нейтронно-активационном анализе, в лучевой терапии опухолей. Кроме того, изотоп 252Cf используется в экспериментах по изучению спонтанного деления ядер. Калифорний является чрезвычайно дорогим металлом. Цена 1 грамма изотопа 252Cf составляет около 4 млн долларов США, и она вполне оправдана, так как ежегодно получают 40—60 миллиграммов[11].

Продукты распада ядер калифорния-252 (252Cf) с энергией порядка 80—100 МэВ используют для бомбардировки и ионизации пробы в спектрометрии (см. Плазменная десорбционная ионизация). При делении ядра 252Cf возникают движущиеся в противоположных направлениях частицы. Одна из частиц попадает в триггерный детектор и сигнализирует о начале отсчёта времени. Другая частица попадает на матрицу пробы, выбивая ионы, которые направляются во времяпролётный масс-спектрометр[12].

Изотоп 249Cf применяют в научных исследованиях. При работе с ним не требуется защита от нейтронного излучения[4]. Калифорний является самым дорогим металлом в мире.[13] Один грамм Калифорния стоит $70 000 000. Мировой запас составляет около 10 граммов, а производится – несколько десятков микрограмм в год. Сложность заключается в том, что элемент Плутоний переходит в элемент Калифорний за 7-8 лет, из-за этого так дорого.

Физиологическое действие[править | править код]

Радионуклид 252Cf высокорадиотоксичен. ПДК в воде открытых водоёмов 1,33⋅10−4 Бк/л.

При поступлении в организм только 0,05 % калифорния попадает в кровь, из этого количества около 65 % попадает в скелет, где он адсорбируется в костной ткани, 25 % — в печень, а остальные 10 % накапливаются в других органах или выводятся из организма[14].

Излучение калифорния нарушает выработку эритроцитов. Калифорний-249 и калифорний-251 испускают гамма-излучение[15].

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ CRC contributors. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (неопр.) / ред. David R. Lide. — 87th ed.. — 2006. — С. 4.56. — ISBN 978-0-8493-0487-3.

- ↑ Редкол.: Кнунянц И. Л. (гл. ред.). Химическая энциклопедия: в 5 т. — Москва: Советская энциклопедия, 1990. — Т. 2. — С. 286. — 671 с. — 100 000 экз.

- ↑ WebElements Periodic Table of the Elements | Californium | crystal structures. Дата обращения: 10 августа 2010. Архивировано 2 сентября 2010 года.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Киселёв, 2008.

- ↑ Jakubke, 1994, p. 166.

- ↑ 1 2 Haire, 2006, p. 1522–1523.

- ↑ 1 2 Haire, 2006, p. 1526.

- ↑ Audi G., Bersillon O., Blachot J., Wapstra A. H. The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties // Nuclear Physics A. — 2003. — Т. 729. — С. 3—128. — doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001. — Bibcode: 2003NuPhA.729….3A.

- ↑ Final Report, Evaluation of nuclear criticality safety data and limits for actinides in transport Архивная копия от 10 июля 2007 на Wayback Machine, Republic of France, Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire, Département de Prévention et d’étude des Accidents.

- ↑ Калифорний. Книги. Наука и техника. Дата обращения: 23 августа 2010. Архивировано 23 августа 2011 года.

- ↑ The Most Expensive Substances in the World -> Californium Архивная копия от 5 мая 2016 на Wayback Machine

- ↑ Р. Сильверстейн и др. Спектрометрическая идентификация органических соединений. — 2011. — С. 16—17. — 575 с. — ISBN 978-5-94-774-392-0.

- ↑ Людмила Фрадкина. В чем скрытый потенциал самого дорогого металла в мире, MK.RU (2022.12.02).

- ↑ ANL contributors. Human Health Fact Sheet: Californium. Argonne National Laboratory (август 2005). Архивировано 21 июля 2011 года.

- ↑ Cunningham, 1968, p. 106.

Литература[править | править код]

- Калифорний / Киселёв Ю. М. // Исландия — Канцеляризмы. — М. : Большая российская энциклопедия, 2008. — С. 521. — (Большая российская энциклопедия : [в 35 т.] / гл. ред. Ю. С. Осипов ; 2004—2017, т. 12). — ISBN 978-5-85270-343-9.

- Cunningham, B. B. Californium // The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. — Reinhold Book Corporation, 1968.

- Haire, Richard G. Californium // The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (англ.) / Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean. — 3rd. — Springer Science+Business Media, 2006. — ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- Concise Encyclopedia Chemistry (неопр.) / Jakubke, Hans-Dieter; Jeschkeit, Hans. — Walter de Gruyter, 1994. — ISBN 978-3-11-011451-5.

Ссылки[править | править код]

- Калифорний на Webelements Архивная копия от 10 октября 2004 на Wayback Machine

Калифорний — искусственный радиоактивный химический элемент. Всего один грамм этого металла стоит $70 000 000, а годовой объем производства — десятки миллиграммов. По своим возможностям он уникален. Всего один микрограмм калифорния испускает 2 млн нейтронов в секунду. Иначе говоря, элемент, размещенный на кончике иглы, обладает силой, способной победить злокачественную опухоль или найти запасы золота в недрах земли. Наибольшее применение нашел изотоп калифорния-252. Сейчас его производят на реакторе СМ-3 в Научно-исследовательском институте атомных реакторов (АО «ГНЦ НИИАР», входит в научный дивизион Госкорпорации «Росатом»). В чем особенность уникального элемента? Почему именно реактор СМ стал местом рождения калифорния? Есть ли спрос на этот металл? Об этот и многом другом «МК» рассказал начальник управления коммерческой деятельности АО «ГНЦ НИИАР» Юрий Топоров.

— Реактор СМ-3 можно назвать местом рождения калифорния-252. Аббревиатура СМ расшифровывается как «самый мощный». Почему? Есть ли причины его так называть?

— Есть разные версии. Так, например, один из создателей этого реактора — физик Савелий Моисеевич Фейнберг. Многие шутили, что СМ можно расшифровать как Савелий Моисеевич. Другой вариант расшифровки СМ — самый мощный.

Сам реактор является исследовательским. В отличие от энергетических атомных станций, он не вырабатывает электроэнергию и предназначен для облучения материалов. Его полезное действие — генерить нейтроны. Мощность реактора всего 100 МВт и ее нельзя назвать рекордной. Например, атомные станции — это тысячи мегаватт, что намного больше. И тут расшифровку как «самый мощный» надо понимать не в буквальном смысле. Реактор СМ генерит рекордный поток нейтронов, поэтому его можно назвать самым мощным. Более того, в реакторе есть специальная область, так называемая нейтронная ловушка, где достигается пик потока нейтронов. Таких реакторов в мире по пальцам пересчитать.

— В НИИАРе получают около 30 изотопов, большую часть — в реакторе СМ-3. В чем главное преимущество этой установки?

— Есть такое понятие, как удельная активность. Чем она выше, тем миниатюрней источник можно сделать, не потеряв его полезные свойства. Источник — это, грубо говоря, двойная (для безопасности) металлическая капсула, внутри которой расположено соединение калифорния. В НИИАРе производится и сам калифорний, и эти «железочки», которые называются закрытыми источниками. Иногда удельная активность является критическим параметром. Например, в медицине, где источник вводится в пациента. Там необходимо, чтобы источник был как можно меньше и при этом давал сильное излучение. В этом смысле «самый мощный» реактор СМ-3 позволяет получать изотопы с уникальной удельной активностью, что открывает пути к изготовлению изделий, которые при другой удельной активности не могли бы быть изготовлены: маленькие, но мощные.

— На СМ-3 получают калифорний. Почему этот металл называют самым дорогим?

— Статьи с заголовками типа «Топ-10 самых дорогих металлов в мире: сколько стоит калифорний-252» — это лукавство. В американском реакторе, который можно считать аналогом нашего, в Ок-Риджской национальной лаборатории за 53 года в сумме было накоплено всего 10 граммов калифорния. И это за 53 года! Когда калифорний вынули из реактора, он начал распадаться. Период распада этого элемента – 2,6 года. К слову, в России первый калифорний был получен в 1970 году — 100 микрограммов. К 1972 году мы накопили 1 микрограмм. В настоящее время мы продаем источники из калифорния для разных целей. Так вот, стоимость калифорния в этих источниках — несколько сотен долларов за микрограмм. Это означает, что грамм будет стоить примерно $70 млн. Сумма огромная. Но дело в том, что этот элемент не измеряется в граммах. Профессионалы всегда улыбаются, когда слышат про стоимость калифорния в граммах. Наш институт в год производит десятки миллиграммов калифорния. Это далеко не грамм.

— Как калифорний получается?

— Если посмотреть на таблицу Менделеева, то последний элемент, существующий в природе, это уран. Все, что тяжелее урана, производится искусственно, путем облучения исходного материала в реакторе. При облучении, поглощая нейтроны, исходный элемент становится тяжелее и трансформируется в другой. До превращения в калифорний элементу приходится пройти большую цепочку изменений. Чтобы получить один миллиграмм, придется затратить около килограмма материала: в процессе облучения что-то распадается, что-то исчезает. Если говорить о реакторном времени, то оно измеряется годами. Например, чтобы от плутония дойти до калифорния и получить его значимое количество, должно пройти 7–8 лет. В итоге мы имеем большой расход стартового материала и длительность облучения. Это определяет стоимость калифорния. Но в цену заложены не только затраты, но и польза, которую элемент приносит. Потребительская, рыночная ценность калифорния очень высока. Элемент уникален по своим возможностям. Всего один микрограмм испускает 2 млн нейтронов в секунду, а поместится этот объем на кончике иглы.

— Где используют калифорний?

— Из этого изотопа можно сделать миниатюрные, но очень мощные источники излучения, которые, например, применяются в медицине. И в России, и в США используют миниатюрные нейтронные источники для облучения раковых опухолей в гинекологии, проктологии и т. д. В пациента вводится миниатюрный источник, который разрушает раковые клетки. Другой пример использования калифорния: нейтроны облучают материал и вызывают его ответную реакцию. Они его активируют. По обратному отклику можно судить о химическом составе того, что вы облучаете: железо, серебро, золото. Называется эта процедура элементный анализ. В СССР был популярен такой анализ. В ходе выполнения горно-буровых работ проводилось каротажное исследование скважины. В пробуренное в породе отверстие опускали нейтронный источник, и по отклику становилось понятно, сколько в скважине содержания золота или серебра. Исходя из результатов исследования (много в скважине золота или мало) делали заключение о ее эффективности.

— Оцените перспективы использования этого изотопа.

— Россия поставляет калифорний, например, в Китай. Превалирует промышленное применение, но есть и медицинский спрос. В принципе, этому изотопу сложно найти новое применение. В основном речь может идти о поддержании мощностей его производства на заданном рынком уровне. Калифорний нельзя перевезти на склад. Через 2,6 года его половина исчезает. Буквально с колес надо делать источники. Наша задача — следовать потребностям рынка и производить столько самого калифорния и его источников, сколько нужно.

Отмечу, что СМ — реактор достаточно возрастной. Он проходил несколько реконструкций, и последняя масштабная модернизация была всего два года назад. Срок действия реактора был продлен еще на 20 лет, а это означает, что «Росатом» смотрит в будущее с оптимизмом. С реакторной точки зрения, наше будущее, будущее наших детей обеспечено.

Поставки калифорния – лишь одно из направлений работы Росатома по производству изотопов для промышленных и медицинских применений. Миниатюрные источники делают возможными диагностику и эффективное лечение онкологических заболеваний, неразрушающий контроль сварных соединений, повышение срока хранения сельхозпродукции. Эта деятельность в полной мере отвечает мировому тренду на реализацию ESG-принципов, достижение Целей устойчивого развития ООН. Росатом намерен и впредь развивать изотопное направление, приближаясь к поставленным ESG-целям.

Реклама. Информация о рекламодателе на сайте www.myatom.ru

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Californium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (KAL-ə-FOR-nee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [251] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Californium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 98 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | f-block groups (no number) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f10 7s2[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 28, 8, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1173 K (900 °C, 1652 °F)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1743 K (1470 °C, 2678 °F) (estimation)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 15.1 g/cm3[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +2, +3, +4, +5[4][5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.3[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of californium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | synthetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 3–4[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-71-3[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after California, where it was discovered | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (1950) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of californium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Californium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Cf and atomic number 98. The element was first synthesized in 1950 at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (then the University of California Radiation Laboratory), by bombarding curium with alpha particles (helium-4 ions). It is an actinide element, the sixth transuranium element to be synthesized, and has the second-highest atomic mass of all elements that have been produced in amounts large enough to see with the naked eye (after einsteinium). The element was named after the university and the U.S. state of California.

Two crystalline forms exist for californium at normal pressure: one above and one below 900 °C (1,650 °F). A third form exists at high pressure. Californium slowly tarnishes in air at room temperature. Californium compounds are dominated by the +3 oxidation state. The most stable of californium’s twenty known isotopes is californium-251, with a half-life of 898 years. This short half-life means the element is not found in significant quantities in the Earth’s crust.[a] 252Cf, with a half-life of about 2.645 years, is the most common isotope used and is produced at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the United States and Research Institute of Atomic Reactors in Russia.

Californium is one of the few transuranium elements with practical applications. Most of these applications exploit the property of certain isotopes of californium to emit neutrons. For example, californium can be used to help start up nuclear reactors, and it is employed as a source of neutrons when studying materials using neutron diffraction and neutron spectroscopy. Californium can also be used in nuclear synthesis of higher mass elements; oganesson (element 118) was synthesized by bombarding californium-249 atoms with calcium-48 ions. Users of californium must take into account radiological concerns and the element’s ability to disrupt the formation of red blood cells by bioaccumulating in skeletal tissue.

Characteristics[edit]

Physical properties[edit]

Californium is a silvery-white actinide metal[11] with a melting point of 900 ± 30 °C (1,650 ± 50 °F) and an estimated boiling point of 1,745 K (1,470 °C; 2,680 °F).[12] The pure metal is malleable and is easily cut with a razor blade. Californium metal starts to vaporize above 300 °C (570 °F) when exposed to a vacuum.[13] Below 51 K (−222 °C; −368 °F) californium metal is either ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic (it acts like a magnet), between 48 and 66 K it is antiferromagnetic (an intermediate state), and above 160 K (−113 °C; −172 °F) it is paramagnetic (external magnetic fields can make it magnetic).[14] It forms alloys with lanthanide metals but little is known about the resulting materials.[13]

The element has two crystalline forms at standard atmospheric pressure: a double-hexagonal close-packed form dubbed alpha (α) and a face-centered cubic form designated beta (β).[b] The α form exists below 600–800 °C with a density of 15.10 g/cm3 and the β form exists above 600–800 °C with a density of 8.74 g/cm3.[16] At 48 GPa of pressure the β form changes into an orthorhombic crystal system due to delocalization of the atom’s 5f electrons, which frees them to bond.[17][c]

The bulk modulus of a material is a measure of its resistance to uniform pressure. Californium’s bulk modulus is 50±5 GPa, which is similar to trivalent lanthanide metals but smaller than more familiar metals, such as aluminium (70 GPa).[17]

Chemical properties and compounds[edit]

| state | compound | formula | color | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +2 | californium(II) bromide | CfBr2 | yellow | |

| +2 | californium(II) iodide | CfI2 | dark violet | |

| +3 | californium(III) oxide | Cf2O3 | yellow-green | |

| +3 | californium(III) fluoride | CfF3 | bright green | |

| +3 | californium(III) chloride | CfCl3 | emerald green | |

| +3 | californium(III) bromide | CfBr3 | yellowish green | |

| +3 | californium(III) iodide | CfI3 | lemon yellow | |

| +3 | californium(III) polyborate | Cf[B6O8(OH)5] | pale green | |

| +4 | californium(IV) oxide | CfO2 | black brown | |

| +4 | californium(IV) fluoride | CfF4 | green |

Californium exhibits oxidation states of 4, 3, or 2. It typically forms eight or nine bonds to surrounding atoms or ions. Its chemical properties are predicted to be similar to other primarily 3+ valence actinide elements[19] and the element dysprosium, which is the lanthanide above californium in the periodic table.[20] Compounds in the +4 oxidation state are strong oxidizing agents and those in the +2 state are strong reducing agents.[11]

The element slowly tarnishes in air at room temperature, with the rate increasing when moisture is added.[16] Californium reacts when heated with hydrogen, nitrogen, or a chalcogen (oxygen family element); reactions with dry hydrogen and aqueous mineral acids are rapid.[16]

Californium is only water-soluble as the californium(III) cation. Attempts to reduce or oxidize the +3 ion in solution have failed.[20] The element forms a water-soluble chloride, nitrate, perchlorate, and sulfate and is precipitated as a fluoride, oxalate, or hydroxide.[19] Californium is the heaviest actinide to exhibit covalent properties, as is observed in the californium borate.[21]

Isotopes[edit]

Twenty isotopes of californium are known (mass number ranging from 237 to 256[10]); the most stable are 251Cf with half-life 898 years, 249Cf with half-life 351 years, 250Cf with half-life 13.08 years, and 252Cf with half-life 2.645 years.[10] All other isotopes have half-life shorter than a year, and most of these have half-life less than 20 minutes.[10]

249Cf is formed from beta decay of berkelium-249, and most other californium isotopes are made by subjecting berkelium to intense neutron radiation in a nuclear reactor.[20] Though californium-251 has the longest half-life, its production yield is only 10% due to its tendency to collect neutrons (high neutron capture) and its tendency to interact with other particles (high neutron cross section).[22]

Californium-252 is a very strong neutron emitter, which makes it extremely radioactive and harmful.[23][24][25] 252Cf, 96.9% of the time, alpha decays to curium-248; the other 3.1% of decays are spontaneous fission.[10] One microgram (μg) of 252Cf emits 2.3 million neutrons per second, an average of 3.7 neutrons per spontaneous fission.[26] Most other isotopes of californium, alpha decay to curium (atomic number 96).[10]

History[edit]

The 60-inch-diameter (1.52 m) cyclotron used to first synthesize californium

Californium was first made at University of California Radiation Laboratory, Berkeley, by physics researchers Stanley Gerald Thompson, Kenneth Street Jr., Albert Ghiorso, and Glenn T. Seaborg, about February 9, 1950.[27] It was the sixth transuranium element to be discovered; the team announced its discovery on March 17, 1950.[28][29]

To produce californium, a microgram-size target of curium-242 (242

96Cm

) was bombarded with 35 MeV alpha particles (4

2He

) in the 60-inch-diameter (1.52 m) cyclotron at Berkeley, which produced californium-245 (245

98Cf

) plus one free neutron (

n

).[27][28]

- 242

96Cm

+ 4

2He

→ 245

98Cf

+ 1

0

n

To identify and separate out the element, ion exchange and adsorsion methods were undertaken.[28][30] Only about 5,000 atoms of californium were produced in this experiment,[31] and these atoms had a half-life of 44 minutes.[27]

The discoverers named the new element after the university and the state. This was a break from the convention used for elements 95 to 97, which drew inspiration from how the elements directly above them in the periodic table were named.[32][e] However, the element directly above #98 in the periodic table, dysprosium, has a name that means “hard to get at”, so the researchers decided to set aside the informal naming convention.[34] They added that “the best we can do is to point out [that] … searchers a century ago found it difficult to get to California”.[33]

Weighable amounts of californium were first produced by the irradiation of plutonium targets at Materials Testing Reactor at National Reactor Testing Station, eastern Idaho; these findings were reported in 1954.[35] The high spontaneous fission rate of californium-252 was observed in these samples. The first experiment with californium in concentrated form occurred in 1958.[27] The isotopes 249Cf to 252Cf were isolated that same year from a sample of plutonium-239 that had been irradiated with neutrons in a nuclear reactor for five years.[11] Two years later, in 1960, Burris Cunningham and James Wallman of Lawrence Radiation Laboratory of the University of California created the first californium compounds—californium trichloride, californium(III) oxychloride, and californium oxide—by treating californium with steam and hydrochloric acid.[36]

The High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, started producing small batches of californium in the 1960s.[37] By 1995, HFIR nominally produced 500 milligrams (0.018 oz) of californium annually.[38] Plutonium supplied by the United Kingdom to the United States under the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement was used for making californium.[39]

The Atomic Energy Commission sold 252Cf to industrial and academic customers in the early 1970s for $10 per microgram,[26] and an average of 150 mg (0.0053 oz) of 252Cf were shipped each year from 1970 to 1990.[40][f] Californium metal was first prepared in 1974 by Haire and Baybarz, who reduced californium(III) oxide with lanthanum metal to obtain microgram amounts of sub-micrometer thick films.[41][42][g]

Occurrence[edit]

Traces of californium can be found near facilities that use the element in mineral prospecting and in medical treatments.[44] The element is fairly insoluble in water, but it adheres well to ordinary soil; and concentrations of it in the soil can be 500 times higher than in the water surrounding the soil particles.[45]

Nuclear fallout from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing prior to 1980 contributed a small amount of californium to the environment.[45] Californium isotopes with mass numbers 249, 252, 253, and 254 have been observed in the radioactive dust collected from the air after a nuclear explosion.[46] Californium is not a major radionuclide at United States Department of Energy legacy sites since it was not produced in large quantities.[45]

Californium was once believed to be produced in supernovas, as their decay matches the 60-day half-life of 254Cf.[47] However, subsequent studies failed to demonstrate any californium spectra,[48] and supernova light curves are now thought to follow the decay of nickel-56.[49]

The transuranium elements from americium to fermium, including californium, occurred naturally in the natural nuclear fission reactor at Oklo, but no longer do so.[50]

Spectral lines of californium, along with those of several other non-primordial elements, were detected in Przybylski’s Star in 2008.[51]

Production[edit]

Californium is produced in nuclear reactors and particle accelerators.[52] Californium-250 is made by bombarding berkelium-249 (249

97Bk

) with neutrons, forming berkelium-250 (250

97Bk

) via neutron capture (n,γ) which, in turn, quickly beta decays (β−) to californium-250 (250

98Cf

) in the following reaction:[53]

- 249

97Bk

(n,γ)250

97Bk

→ 250

98Cf

+ β−

Bombardment of californium-250 with neutrons produces californium-251 and californium-252.[53]

Prolonged irradiation of americium, curium, and plutonium with neutrons produces milligram amounts of californium-252 and microgram amounts of californium-249.[54] As of 2006, curium isotopes 244 to 248 are irradiated by neutrons in special reactors to produce primarily californium-252 with lesser amounts of isotopes 249 to 255.[55]

Microgram quantities of californium-252 are available for commercial use through the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.[52] Only two sites produce californium-252: the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the United States, and the Research Institute of Atomic Reactors in Dimitrovgrad, Russia. As of 2003, the two sites produce 0.25 grams and 0.025 grams of californium-252 per year, respectively.[56]

Three californium isotopes with significant half-lives are produced, requiring a total of 15 neutron captures by uranium-238 without nuclear fission or alpha decay occurring during the process.[56] Californium-253 is at the end of a production chain that starts with uranium-238, includes several isotopes of plutonium, americium, curium, berkelium, and the californium isotopes 249 to 253 (see diagram).

Scheme of the production of californium-252 from uranium-238 by neutron irradiation

Applications[edit]

Fifty-ton shipping cask built at Oak Ridge National Laboratory which can transport up to 1 gram of 252Cf.[57] Large and heavily shielded transport containers are needed to prevent the release of highly radioactive material in case of normal and hypothetical accidents.[58]

Californium-252 has a number of specialized uses as a strong neutron emitter; it produces 139 million neutrons per microgram per minute.[26] This property makes it useful as a startup neutron source for some nuclear reactors[16] and as a portable (non-reactor based) neutron source for neutron activation analysis to detect trace amounts of elements in samples.[59][h] Neutrons from californium are used as a treatment of certain cervical and brain cancers where other radiation therapy is ineffective.[16] It has been used in educational applications since 1969 when Georgia Institute of Technology got a loan of 119 μg of 252Cf from the Savannah River Site.[61] It is also used with online elemental coal analyzers and bulk material analyzers in the coal and cement industries.

Neutron penetration into materials makes californium useful in detection instruments such as fuel rod scanners;[16] neutron radiography of aircraft and weapons components to detect corrosion, bad welds, cracks and trapped moisture;[62] and in portable metal detectors.[63] Neutron moisture gauges use 252Cf to find water and petroleum layers in oil wells, as a portable neutron source for gold and silver prospecting for on-the-spot analysis,[20] and to detect ground water movement.[64] The main uses of 252Cf in 1982 were, reactor start-up (48.3%), fuel rod scanning (25.3%), and activation analysis (19.4%).[65] By 1994, most 252Cf was used in neutron radiography (77.4%), with fuel rod scanning (12.1%) and reactor start-up (6.9%) as important but secondary uses.[65] In 2021, fast neutrons from 252Cf were used for wireless data transmission.[66]

251Cf has a very small calculated critical mass of about 5 kg (11 lb),[67] high lethality, and a relatively short period of toxic environmental irradiation. The low critical mass of californium led to some exaggerated claims about possible uses for the element.[i]

In October 2006, researchers announced that three atoms of oganesson (element 118) had been identified at Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, from bombarding 249Cf with calcium-48, making it the heaviest element ever made. The target contained about 10 mg of 249Cf deposited on a titanium foil of 32 cm2 area.[69][70][71] Californium has also been used to produce other transuranium elements; for example, lawrencium was first synthesized in 1961 by bombarding californium with boron nuclei.[72]

Precautions[edit]

Californium that bioaccumulates in skeletal tissue releases radiation that disrupts the body’s ability to form red blood cells.[73] The element plays no natural biological role in any organism due to its intense radioactivity and low concentration in the environment.[44]

Californium can enter the body from ingesting contaminated food or drinks or by breathing air with suspended particles of the element. Once in the body, only 0.05% of the californium will reach the bloodstream. About 65% of that californium will be deposited in the skeleton, 25% in the liver, and the rest in other organs, or excreted, mainly in urine. Half of the californium deposited in the skeleton and liver are gone in 50 and 20 years, respectively. Californium in the skeleton adheres to bone surfaces before slowly migrating throughout the bone.[45]

The element is most dangerous if taken into the body. In addition, californium-249 and californium-251 can cause tissue damage externally, through gamma ray emission. Ionizing radiation emitted by californium on bone and in the liver can cause cancer.[45]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The Earth formed 4.5 billion years ago, and the extent of natural neutron emission within it that could produce californium from more stable elements is extremely limited.

- ^ A double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) unit cell consists of two hexagonal close-packed structures that share a common hexagonal plane, giving dhcp an ABACABAC sequence.[15]

- ^ The three lower-mass transplutonium elements—americium, curium, and berkelium—require much less pressure to delocalize their 5f electrons.[17]

- ^ Other +3 oxidation states include the sulfide and metallocene.[18]

- ^ Europium, in the sixth period directly above element 95, was named for the continent it was discovered on, so element 95 was named americium. Element 96 was named curium for Marie Curie and Pierre Curie as an analog to the naming of gadolinium, which was named for the scientist and engineer Johan Gadolin. Terbium was named for the village it was discovered in, so element 97 was named berkelium.[33]

- ^ The Nuclear Regulatory Commission replaced the Atomic Energy Commission when the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 was implemented. The price of californium-252 was increased by the NRC several times and was $60 per microgram by 1999; this price does not include the cost of encapsulation and transportation.[26]

- ^ In 1975, another paper stated that the californium metal prepared the year before was the hexagonal compound Cf2O2S and face-centered cubic compound CfS.[43] The 1974 work was confirmed in 1976 and work on californium metal continued.[41]

- ^ By 1990, californium-252 had replaced plutonium-beryllium neutron sources due to its smaller size and lower heat and gas generation.[60]

- ^ An article entitled “Facts and Fallacies of World War III” in the July 1961 edition of Popular Science magazine read “A californium atomic bomb need be no bigger than a pistol bullet. You could build a hand-held six-shooter to fire bullets that would explode on contact with the force of 10 tons of TNT.”[68]

References[edit]

- ^ CRC 2006, p. 1.14.

- ^ a b c CRC 2006, p. 4.56.

- ^

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1265. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Kovács, Attila; Dau, Phuong D.; Marçalo, Joaquim; Gibson, John K. (2018). “Pentavalent Curium, Berkelium, and Californium in Nitrate Complexes: Extending Actinide Chemistry and Oxidation States”. Inorg. Chem. American Chemical Society. 57 (15): 9453–9467. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01450. OSTI 1631597. PMID 30040397. S2CID 51717837.

- ^ Emsley 1998, p. 50.

- ^ CRC 2006, p. 10.204.

- ^ CRC 1991, p. 254.

- ^ CRC 2006, p. 11.196.

- ^ a b c d e f Sonzogni, Alejandro A. (Database Manager), ed. (2008). “Chart of Nuclides”. National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Jakubke 1994, p. 166.

- ^ Haire 2006, pp. 1522–1523.

- ^ a b Haire 2006, p. 1526.

- ^ Haire 2006, p. 1525.

- ^ Szwacki 2010, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e f O’Neil 2006, p. 276.

- ^ a b c Haire 2006, p. 1522.

- ^ Cotton et al. 1999, p. 1163.

- ^ a b Seaborg 2004.

- ^ a b c d CRC 2006, p. 4.8.

- ^ Polinski, Matthew J.; Iii, Edward B. Garner; Maurice, Rémi; Planas, Nora; Stritzinger, Jared T.; Parker, T. Gannon; Cross, Justin N.; Green, Thomas D.; Alekseev, Evgeny V. (May 1, 2014). “Unusual structure, bonding and properties in a californium borate”. Nature Chemistry. 6 (5): 387–392. Bibcode:2014NatCh…6..387P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.646.749. doi:10.1038/nchem.1896. ISSN 1755-4330. PMID 24755589.

- ^ Haire 2006, p. 1504.

- ^ Hicks, D. A.; Ise, John; Pyle, Robert V. (1955). “Multiplicity of Neutrons from the Spontaneous Fission of Californium-252”. Physical Review. 97 (2): 564–565. Bibcode:1955PhRv…97..564H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.97.564.

- ^ Hicks, D. A.; Ise, John; Pyle, Robert V. (1955). “Spontaneous-Fission Neutrons of Californium-252 and Curium-244”. Physical Review. 98 (5): 1521–1523. Bibcode:1955PhRv…98.1521H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.98.1521.

- ^ Hjalmar, E.; Slätis, H.; Thompson, S.G. (1955). “Energy Spectrum of Neutrons from Spontaneous Fission of Californium-252”. Physical Review. 100 (5): 1542–1543. Bibcode:1955PhRv..100.1542H. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.100.1542.

- ^ a b c d Martin, R. C.; Knauer, J. B.; Balo, P. A. (1999). “Production, Distribution, and Applications of Californium-252 Neutron Sources”. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 53 (4–5): 785–92. doi:10.1016/S0969-8043(00)00214-1. PMID 11003521.

- ^ a b c d Cunningham 1968, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Street, K. Jr.; Thompson, S. G.; Seaborg, Glenn T. (1950). “Chemical Properties of Californium” (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72 (10): 4832. doi:10.1021/ja01166a528. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086449173. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ Glenn Theodore Seaborg (1990). Journal of Glenn T. Seaborg, 1946–1958: January 1, 1950 – December 31, 1950. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, University of California. p. 80.

- ^ Thompson, S. G.; Street, K. Jr.; A., Ghiorso; Seaborg, Glenn T. (1950). “Element 98”. Physical Review. 78 (3): 298. Bibcode:1950PhRv…78..298T. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.78.298.2.

- ^ Seaborg 1996, p. 82.

- ^ Weeks & Leichester 1968, p. 849.

- ^ a b Weeks & Leichester 1968, p. 848.

- ^ Heiserman 1992, p. 347.

- ^ Diamond, H.; Magnusson, L.; Mech, J.; Stevens, C.; Friedman, A.; Studier, M.; Fields, P.; Huizenga, J. (1954). “Identification of Californium Isotopes 249, 250, 251, and 252 from Pile-Irradiated Plutonium”. Physical Review. 94 (4): 1083. Bibcode:1954PhRv…94.1083D. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.94.1083.

- ^ “Element 98 Prepared”. Science News Letter. 78 (26). December 1960.

- ^ “The High Flux Isotope Reactor”. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Osborne-Lee 1995, p. 11.

- ^ “Plutonium and Aldermaston – an Historical Account” (PDF). UK Ministry of Defence. September 4, 2001. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Osborne-Lee 1995, p. 6.

- ^ a b Haire 2006, p. 1519.

- ^ Haire, R. G.; Baybarz, R. D. (1974). “Crystal Structure and Melting Point of Californium Metal”. Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 36 (6): 1295. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(74)80067-9.

- ^ Zachariasen, W. (1975). “On Californium Metal”. Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 37 (6): 1441–1442. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(75)80787-1.

- ^ a b Emsley 2001, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e “Human Health Fact Sheet: Californium” (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. August 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011.

- ^ Fields, P. R.; Studier, M.; Diamond, H.; Mech, J.; Inghram, M.; Pyle, G.; Stevens, C.; Fried, S.; et al. (1956). “Transplutonium Elements in Thermonuclear Test Debris”. Physical Review. 102 (1): 180–182. Bibcode:1956PhRv..102..180F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.102.180.

- ^ Baade, W.; Burbidge, G. R.; Hoyle, F.; Burbidge, E. M.; Christy, R. F.; Fowler, W. A. (August 1956). “Supernovae and Californium 254” (PDF). Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 68 (403): 296–300. Bibcode:1956PASP…68..296B. doi:10.1086/126941. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ Conway, J. G.; Hulet, E.K.; Morrow, R.J. (February 1, 1962). “Emission Spectrum of Californium”. Journal of the Optical Society of America. 52 (2): 222. doi:10.1364/josa.52.000222. OSTI 4806792. PMID 13881026.

- ^ Ruiz-Lapuente1996, p. 274.

- ^ Emsley, John (2011). Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements (New ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ Gopka, V. F.; Yushchenko, A. V.; Yushchenko, V. A.; Panov, I. V.; Kim, Ch. (May 15, 2008). “Identification of absorption lines of short half-life actinides in the spectrum of Przybylski’s star (HD 101065)”. Kinematics and Physics of Celestial Bodies. 24 (2): 89–98. Bibcode:2008KPCB…24…89G. doi:10.3103/S0884591308020049. S2CID 120526363.

- ^ a b Krebs 2006, pp. 327–328.

- ^ a b Heiserman 1992, p. 348.

- ^ Cunningham 1968, p. 105.

- ^ Haire 2006, p. 1503.

- ^ a b NRC 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Seaborg 1994, p. 245.

- ^ Shuler, James (2008). “DOE Certified Radioactive Materials Transportation Packagings” (PDF). United States Department of Energy. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Martin, R. C. (September 24, 2000). Applications and Availability of Californium-252 Neutron Sources for Waste Characterization (PDF). Spectrum 2000 International Conference on Nuclear and Hazardous Waste Management. Chattanooga, Tennessee. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 1, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Seaborg 1990, p. 318.

- ^ Osborne-Lee 1995, p. 33.

- ^ Osborne-Lee 1995, pp. 26–27.

- ^ “Will You be ‘Mine’? Physics Key to Detection”. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. October 25, 2000. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ Davis, S. N.; Thompson, Glenn M.; Bentley, Harold W.; Stiles, Gary (2006). “Ground-Water Tracers – A Short Review”. Ground Water. 18 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.1980.tb03366.x.

- ^ a b Osborne-Lee 1995, p. 12.

- ^ Joyce, Malcolm J.; Aspinall, Michael D.; Clark, Mackenzie; Dale, Edward; Nye, Hamish; Parker, Andrew; Snoj, Luka; Spires, Joe (2022). “Wireless information transfer with fast neutrons”. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 1021 (1): 165946. Bibcode:2022NIMPA102165946J. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2021.165946. ISSN 0168-9002. S2CID 240341300.

- ^ “Evaluation of nuclear criticality safety data and limits for actinides in transport” (PDF). Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 19, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ Mann, Martin (July 1961). “Facts and Fallacies of World War III”. Popular Science. 179 (1): 92–95, 178–181. ISSN 0161-7370.“force of 10 tons of TNT” on page 180.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Utyonkov, V.; Lobanov, Yu.; Abdullin, F.; Polyakov, A.; Sagaidak, R.; Shirokovsky, I.; Tsyganov, Yu.; et al. (2006). “Synthesis of the isotopes of elements 118 and 116 in the californium-249 and 245Cm+48Ca fusion reactions”. Physical Review C. 74 (4): 044602–044611. Bibcode:2006PhRvC..74d4602O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.74.044602.

- ^ Sanderson, K. (October 17, 2006). “Heaviest element made – again”. Nature News. Nature. doi:10.1038/news061016-4. S2CID 121148847.

- ^ Schewe, P.; Stein, B. (October 17, 2006). “Elements 116 and 118 Are Discovered”. Physics News Update. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved October 19, 2006.

- ^ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (April 1961). “Element 103 Synthesized”. Science News-Letter. 79 (17): 259. doi:10.2307/3943043. JSTOR 3943043.

- ^ Cunningham 1968, p. 106.

Bibliography[edit]

- Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-19957-1.

- Cunningham, B. B. (1968). “Californium”. In Hampel, Clifford A. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. Reinhold Book Corporation. LCCN 68029938.

- Emsley, John (1998). The Elements. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855818-7.

- Emsley, John (2001). “Californium”. Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.

- Haire, Richard G. (2006). “Californium”. In Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- Heiserman, David L. (1992). “Element 98: Californium”. Exploring Chemical Elements and their Compounds. TAB Books. ISBN 978-0-8306-3018-9.

- Jakubke, Hans-Dieter; Jeschkeit, Hans, eds. (1994). Concise Encyclopedia Chemistry. trans. rev. Eagleson, Mary. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-011451-5.

- Krebs, Robert (2006). The History and Use of our Earth’s Chemical Elements: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33438-2.

- Lide, David R., ed. (2006). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-8493-0487-3.

- National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Radiation Source Use and Replacement (2008). Radiation Source Use and Replacement: Abbreviated Version. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-11014-3.

- O’Neil, Marydale J.; Heckelman, Patricia E.; Roman, Cherie B., eds. (2006). The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (14th ed.). Merck Research Laboratories, Merck & Co. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- Osborne-Lee, I. W.; Alexander, C. W. (1995). “Californium-252: A Remarkable Versatile Radioisotope”. Oak Ridge Technical Report ORNL/TM-12706. doi:10.2172/205871.

- Ruiz-Lapuente, P.; Canal, R.; Isern, J. (1996). Thermonuclear Supernovae. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-7923-4359-2.

- Seaborg, Glenn T.; Loveland, Walter D. (1990). The Elements Beyond Uranium. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-89062-1.

- Seaborg, Glenn T. (1994). Modern alchemy: selected papers of Glenn T. Seaborg. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-1440-1.

- Seaborg, Glenn T. (1996). Adloff, J. P. (ed.). One Hundred Years after the Discovery of Radioactivity. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 978-3-486-64252-0.

- Seaborg, Glenn T. (2004). “Californium”. In Geller, Elizabeth (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry. McGraw-Hill. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-07-143953-4.

- Szwacki, Nevill Gonzalez; Szwacka, Teresa (2010). Basic Elements of Crystallography. Pan Stanford. ISBN 978-981-4241-59-5.

- Walker, Perrin; Tarn, William H., eds. (1991). Handbook of Metal Etchants. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-3623-2.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira; Leichester, Henry M. (1968). “21: Modern Alchemy”. Discovery of the Elements. Journal of Chemical Education. pp. 848–850. ISBN 978-0-7661-3872-8. LCCN 68015217.

External links[edit]

Look up californium in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Californium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- NuclearWeaponArchive.org – Californium

- Hazardous Substances Databank – Californium, Radioactive

Media related to Californium at Wikimedia Commons