The accepted answer is correct, but there is a more clever/efficient way to do this if you need to convert a whole bunch of ASCII characters to their ASCII codes at once. Instead of doing:

for ch in mystr:

code = ord(ch)

or the slightly faster:

for code in map(ord, mystr):

you convert to Python native types that iterate the codes directly. On Python 3, it’s trivial:

for code in mystr.encode('ascii'):

and on Python 2.6/2.7, it’s only slightly more involved because it doesn’t have a Py3 style bytes object (bytes is an alias for str, which iterates by character), but they do have bytearray:

# If mystr is definitely str, not unicode

for code in bytearray(mystr):

# If mystr could be either str or unicode

for code in bytearray(mystr, 'ascii'):

Encoding as a type that natively iterates by ordinal means the conversion goes much faster; in local tests on both Py2.7 and Py3.5, iterating a str to get its ASCII codes using map(ord, mystr) starts off taking about twice as long for a len 10 str than using bytearray(mystr) on Py2 or mystr.encode('ascii') on Py3, and as the str gets longer, the multiplier paid for map(ord, mystr) rises to ~6.5x-7x.

The only downside is that the conversion is all at once, so your first result might take a little longer, and a truly enormous str would have a proportionately large temporary bytes/bytearray, but unless this forces you into page thrashing, this isn’t likely to matter.

В этом уроке мы узнаем, как найти значение кода символа ASCII в Python и отобразить результат. ASCII — это аббревиатура, обозначающая американский стандартный код для обмена информацией. Определенное числовое значение дается различным символам, которые компьютеры должны хранить и обрабатывать в ASCII.

ASCII чувствительна к регистру. Один и тот же символ, имеющий разный формат (верхний и нижний регистр), имеет разное значение. Например, значение ASCII “A” равно 65, а значение ASCII “a” равно 97.

Пример 1:

K = input("Please enter a character: ")

print("The ASCII value of '" + K + "' is ", ord(K))

Выход:

1#

Please enter a character: J The ASCII value of 'J' is 74

2#

Please enter a character: $ The ASCII value of '$' is 36

В приведенном выше коде мы использовали функцию ord() для преобразования символа в целое число, то есть значение ASCII. Эта функция используется для возврата кодовой точки Unicode данного символа.

Пример 2:

print("Please enter the String: ", end = "")

string = input()

string_length = len(string)

for K in string:

ASCII = ord(K)

print(K, "t", ASCII)

Выход:

Please enter the String: "JavaTpoint# " 34 J 74 a 97 v 118 a 97 T 84 p 112 o 111 i 105 n 110 t 116 # 35

Юникод также является методом кодирования, который используется для получения уникального номера символа. Хотя ASCII может кодировать только 128 символов, тогда как текущий Unicode может кодировать более 100 000 символов из сотен сценариев.

Мы также можем преобразовать значение ASCII в соответствующее символьное значение. Для этого мы должны использовать chr() вместо ord() в приведенном выше коде.

Пример 3:

K = 21

J = 123

R = 76

print("The character value of 'K' ASCII value is: ", chr(K))

print("The character value of 'J' ASCII value is: ", chr(J))

print("The character value of 'R' ASCII value is: ", chr(R))

Выход:

The character value of 'K' ASCII value is:

The character value of 'J' ASCII value is: {

The character value of 'R' ASCII value is: L

Заключение

В этом руководстве мы обсудили, как пользователь может преобразовать значение символа в значение ASCII, а также как получить значение символа данного кода ASCII.

Изучаю Python вместе с вами, читаю, собираю и записываю информацию опытных программистов.

Работа с кодировкой символов на Python, да и на любом другом языке, временами выглядит довольно сложной. На Stack Overflow можно найти тысячи вопросов, посвящённых таким исключениям, как UnicodeDecodeError и UnicodeEncodeError. Данное руководство призвано прояснить сложные аспекты работы с этими исключениями и продемонстрировать, что работа с текстовыми и двоичными данными на Python 3 может быть приятной. В Python хорошо реализована поддержка Юникода, однако для работы с кодировкой всё же потребуется приложить усилия.

Вводная часть статьи даст общее понимание работы с Юникодом, не привязанное к какому-то определённому языку, однако практические примеры будут приведены именно на Python, а их описание будет довольно лаконичным.

Изучив эту статью, вы:

- Освоите концепции кодировки символов и системы нумерации;

- Поймёте, как кодировка работает с объектами

strиbytes; - Узнаете, как в Python поддерживается система нумерации посредством различных форм литералов

int; - Познакомитесь со встроенными функциями языка, относящимися к кодировке и системе нумерации.

Система нумерации и кодировка символов настолько тесно связаны, что их придётся раскрыть в одном руководстве, в противном случае материал будет неполным.

Прим. Статья ориентирована на Python 3, а все примеры кода созданы с помощью оболочки CPython 3.7.2. Большая часть более ранних версий Python 3 также будут корректно обрабатывать код. Если вы всё ещё используете Python 2 и различия в обработке текста и бинарных данных между 2 и 3 версиями языка вас отпугивают, это руководство может помочь вам преодолеть барьер.

Что такое кодировка символов?

Существуют десятки, если не сотни, кодировок символов. Понять эту концепцию легче всего, разобрав одну из самых простых, ASCII.

Независимо от того, занимаетесь вы самообразованием или получили более формальное образование в сфере IT , наверняка пару раз вы уже видели таблицу ASCII. Эта таблица — хорошее начало для изучения принципов кодировки, так как она простая и маленькая (как вы увидите дальше, даже слишком маленькая).

Она охватывает следующее:

- Символы английского алфавита в нижнем регистре: от a до z;

- Символы английского алфавита в верхнем регистре: от A до Z;

- Некоторые знаки препинания и символы: например «$» или «!»;

- Символы, отображаемые как пустое место: пробел (« »), символ новой строки, возврата каретки, горизонтальной и вертикальной табуляции и несколько других;

- Некоторые непечатаемые символы: такие как бекспейс, «b», которые просто невозможно отобразить, так, как к примеру, букву А.

Приведём формальное определение кодировки символов.

На самом высоком уровне — это способ перевода символов (таких как буквы, знаки пунктуации, служебные знаки, пробелы и контрольные символы) в целые числа и затем непосредственно в биты. Каждый символ может быть закодирован уникальным двоичным кодом. Если вы плохо знакомы с концепцией битов, не волнуйтесь, мы вскоре о ней поговорим.

Группы символов выделяют в отдельные категории. Каждому символу соответствует кодовая точка, которую можно рассматривать просто как целое число. В таблице ASCII символы сегментированы следующим образом:

| Диапазон кодовых точек | Класс |

|---|---|

| от 0 до 31 | Контрольные и неотображаемые символы |

| от 32 до 64 | Знаки пунктуации, символы, числа и пробел |

| от 65 до 90 | Буквы английского алфавита в верхнем регистре |

| от 91 до 96 | Дополнительные графемы, такие как [ и |

| от 97 до 122 | Буквы английского алфавита в нижнем регистре |

| от 123 до 126 | Дополнительные графемы, такие как { и | |

| 127 | Контрольный неотображаемый символ (DEL) |

Всего кодировка ASCII содержит 128 символов. В таблице ниже вы видите исчерпывающий набор знаков, которые позволяет отобразить эта кодировка. Если вы не видите какого-то символа, значит вы просто не сможете его вывести с помощью ASCII.

| Кодовая точка | Символ (имя) | Кодовая точка | Символ (имя) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NUL (Null) | 64 | @ |

| 1 | SOH (Start of Heading) | 65 | A |

| 2 | STX (Start of Text) | 66 | B |

| 3 | ETX (End of Text) | 67 | C |

| 4 | EOT (End of Transmission) | 68 | D |

| 5 | ENQ (Enquiry) | 69 | E |

| 6 | ACK (Acknowledgment) | 70 | F |

| 7 | BEL (Bell) | 71 | G |

| 8 | BS (Backspace) | 72 | H |

| 9 | HT (Horizontal Tab) | 73 | I |

| 10 | LF (Line Feed) | 74 | J |

| 11 | VT (Vertical Tab) | 75 | K |

| 12 | FF (Form Feed) | 76 | L |

| 13 | CR (Carriage Return) | 77 | M |

| 14 | SO (Shift Out) | 78 | N |

| 15 | SI (Shift In) | 79 | O |

| 16 | DLE (Data Link Escape) | 80 | P |

| 17 | DC1 (Device Control 1) | 81 | Q |

| 18 | DC2 (Device Control 2) | 82 | R |

| 19 | DC3 (Device Control 3) | 83 | S |

| 20 | DC4 (Device Control 4) | 84 | T |

| 21 | NAK (Negative Acknowledgment) | 85 | U |

| 22 | SYN (Synchronous Idle) | 86 | V |

| 23 | ETB (End of Transmission Block) | 87 | W |

| 24 | CAN (Cancel) | 88 | X |

| 25 | EM (End of Medium) | 89 | Y |

| 26 | SUB (Substitute) | 90 | Z |

| 27 | ESC (Escape) | 91 | [ |

| 28 | FS (File Separator) | 92 | |

| 29 | GS (Group Separator) | 93 | ] |

| 30 | RS (Record Separator) | 94 | ^ |

| 31 | US (Unit Separator) | 95 | _ |

| 32 | SP (Space) | 96 | ` |

| 33 | ! |

97 | a |

| 34 | " |

98 | b |

| 35 | # |

99 | c |

| 36 | $ |

100 | d |

| 37 | % |

101 | e |

| 38 | & |

102 | f |

| 39 | ' |

103 | g |

| 40 | ( |

104 | h |

| 41 | ) |

105 | i |

| 42 | * |

106 | j |

| 43 | + |

107 | k |

| 44 | , |

108 | l |

| 45 | - |

109 | m |

| 46 | . |

110 | n |

| 47 | / |

111 | o |

| 48 | 0 |

112 | p |

| 49 | 1 |

113 | q |

| 50 | 2 |

114 | r |

| 51 | 3 |

115 | s |

| 52 | 4 |

116 | t |

| 53 | 5 |

117 | u |

| 54 | 6 |

118 | v |

| 55 | 7 |

119 | w |

| 56 | 8 |

120 | x |

| 57 | 9 |

121 | y |

| 58 | : |

122 | z |

| 59 | ; |

123 | { |

| 60 | < |

124 | | |

| 61 | = |

125 | } |

| 62 | > |

126 | ~ |

| 63 | ? |

127 | DEL (delete) |

Модуль string

Модуль string — простой и удобный инструмент, разграничивающий содержащиеся в ASCII символы по группам, разделяя их в строки-константы. Вот как выглядит основная часть модуля:

# From lib/python3.7/string.py

whitespace = ' tnrvf'

ascii_lowercase = 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

ascii_uppercase = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

ascii_letters = ascii_lowercase + ascii_uppercase

digits = '0123456789'

hexdigits = digits + 'abcdef' + 'ABCDEF'

octdigits = '01234567'

punctuation = r"""!"#$%&'()*+,-./:;<=>?@[]^_`{|}~"""

printable = digits + ascii_letters + punctuation + whitespaceБольшинство этих констант исчерпывающе описаны их идентификаторами. Мы вкратце коснёмся констант hexdigits и octdigits.

Мы можем использовать определённые в модуле константы для рутинных операций:

>>> import string

>>> s = "What's wrong with ASCII?!?!?"

>>> s.rstrip(string.punctuation)

'What's wrong with ASCII'Прим. Обратите внимание, string.printable включает string.whitespace. Это несколько не соответствует тому, как печатаемые символы определяет метод str.isprintable(), который не рассматривает ни один из символов {'v', 'n', 'r', 'f', 't'} как печатаемый.

Это различие происходит из определения метода: str.isprintable() рассматривает что-либо печатаемым, если «все символы рассматриваются как печатаемые методом repr().

Что такое биты

Настало время вспомнить, что такое бит, базовая единица информации, которой оперируют вычислительные устройства.

Бит — это сигнал, который имеет два возможных состояния. Есть различные способы символического отображения этих состояний:

- 0 или 1;

- «да» или «нет»;

TrueилиFalse;- «включено» или «выключено».

Таблица ASCII из предыдущего раздела использует то, что обычно назвали бы числами (от 0 до 127), однако для наших целей важно понимать, что это десятичные числа (с основанием 10).

Каждое из этих десятичных чисел можно выразить последовательностью бит (числом с основанием 2). Вот таблица соотношения двоичных и десятичных чисел:

| Десятичное | Двоичное (кратко) | Двоичное (в байте) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 00000000 |

| 1 | 1 | 00000001 |

| 2 | 10 | 00000010 |

| 3 | 11 | 00000011 |

| 4 | 100 | 00000100 |

| 5 | 101 | 00000101 |

| 6 | 110 | 00000110 |

| 7 | 111 | 00000111 |

| 8 | 1000 | 00001000 |

| 9 | 1001 | 00001001 |

| 10 | 1010 | 00001010 |

Обратите внимание, что при увеличении десятичного числа n для его отображения (а следовательно и для отображения символа, относящегося к этому числу) требуется всё больше значимых бит.

Вот удобный метод представить строки ASCII как последовательность бит. Каждый символ из строки ASCII переводится в последовательность из 8 нолей и единиц с пробелами между этими последовательностями:

>>> def make_bitseq(s: str) -> str:

... if not s.isascii():

... raise ValueError("ASCII only allowed")

... return " ".join(f"{ord(i):08b}" for i in s)

>>> make_bitseq("bits")

'01100010 01101001 01110100 01110011'

>>> make_bitseq("CAPS")

'01000011 01000001 01010000 01010011'

>>> make_bitseq("$25.43")

'00100100 00110010 00110101 00101110 00110100 00110011'

>>> make_bitseq("~5")

'01111110 00110101'Прим. Обратите внимание, что метод .isascii() появился в Python 3.7.

Строковой литерал f-string f"{ord(i):08b}" использует мини-язык форматирования Format Specification Mini-Language, а именно его возможность замещения полей при форматировании строк.

- левая часть выражения,

ord(i), представляет объект, значение которого будет отформатировано и отображено при выводе.ord()возвращает кодовую точку одиночного символаstrв десятичном выражении; - Правая сторона выражения определяет форматирование объекта.

08означает ширина 8, заполнение нулями, аbработает как команда вывести число в двоичном (binary) эквиваленте.

На самом деле этот метод можно использовать разве что для развлечения. Он выдаст ошибку для любого символа, не представленного в ASCII-таблице. Позже мы рассмотрим, как эта проблема решается в других кодировках.

Нам нужно больше бит

Исходя из определения бита, можно вывести следующую закономерность: при определённом количестве бит n с их помощью можно выразить 2n разных значений.

def n_possible_values(nbits: int) -> int:

return 2 ** nbitsВот что это означает:

- 1 бит позволяет выразить 21 == 2 возможных значения;

- 8 бит позволяют выразить 28 == 256 возможных значений;

- 64 бита позволяют выразить 264 == 18 446 744 073 709 551 616 возможных значений.

В качестве естественного вывода из приведённой выше формулы мы можем установить следующее: для того, чтобы вычислить количество бит, необходимых для выражения определённого числа разных значений, нам нужно найти n в уравнении 2n=x, где переменная x известна.

Вот как можно это рассчитать:

>>> from math import ceil, log

>>> def n_bits_required(nvalues: int) -> int:

... return ceil(log(nvalues) / log(2))

>>> n_bits_required(256)

8Округление вверх в методе n_bits_required() требуется для расчёта значений, которые не являются чистой степенью двойки. К примеру, вам нужно сохранить набор из 110 различных символов. Для этого потребуется log(110) / log(2) == 6.781 бит, но поскольку бит для вычислительной техники является мельчайшей неделимой величиной, для отображения 110 различных значений нам понадобится 7 бит, при этом несколько значений останутся невостребованными.

>>> n_bits_required(110)

7Всё сказанное служит для обоснования одной идеи: ASCII, строго говоря, семибитная кодировка. Эта таблица содержит 128 кодовых точек, и, соответственно, символов, от 0 до 127 включительно. Это требует 7 бит:

>>> n_bits_required(128) # от 0 до 127

7

>>> n_possible_values(7)

128Проблема заключается в том, что современные компьютеры не используют для хранения чего-либо семибитные последовательности. Основной единицей хранения информации современных вычислительных устройств являются восьмибитные последовательности, байты.

Прим. В этой статье под байтом подразумевается группа из 8 бит, как повелось с 60-х годов прошлого века. Если вам не по душе это новомодное название, можете называть их октетами.

То, что ASCII-таблица использует 7 бит из доступных 8, означает, что память вычислительного устройства, занятого строками символов ASCII, наполовину пуста. Для того, чтобы лучше понять, почему это происходит, вернитесь к приведённой выше таблице соответствия двоичных и десятичных чисел. Вы можете выразить числа 0 и 1 с помощью 1 бита, или вы можете использовать 8 бит, чтобы выразить их как 00000000 и 00000001 соответственно.

Прим. перев. Если быть точным, то пустой остаётся только одна восьмая часть памяти. Однако с помощью именно этого незадействованного бита можно было бы создать вдвое больше кодовых точек.

Вы можете выразить числа от 0 до 3 всего двумя битами, от 00 до 11, или использовать 8 бит, чтобы выразить их как 00000000, 00000001, 00000010 и 00000011. Самая большая кодовая точка ASCII, 127, требует только 7 значимых бит.

С учётом этого взгляните, как метод make_bitseq() преобразует строки ASCII в строки, состоящие из байт, где каждый символ требует один байт:

>>> make_bitseq("bits")

'01100010 01101001 01110100 01110011'Неэффективное использование восьмибитной структуры памяти современных вычислительных устройств привело к появлению неструктурированного семейства конфликтующих кодировок, задействующих оставшуюся незанятой половину кодовых точек, доступных в одном байте.

Несмотря на попытку задействовать дополнительный бит, эти конфликтующие кодировки не могли отобразить все возможные символы, используемые человечеством в письменности.

Со временем появилась одна большая схема кодировки, которая объединила их. Однако, прежде чем мы до этого доберёмся, поговорим немного о краеугольных камнях схем кодировки символов — системах счисления.

Изучаем основы: другие системы счисления

В ASCII-таблице, как мы увидели, каждый символ соответствует числу от 0 до 127.

Этот диапазон чисел выражен в десятичной системе счисления. Именно эту систему используют для счёта люди, просто потому что на руках у нас по 10 пальцев.

Однако существуют и другие системы счисления, которые, в частности, широко используются в исходном коде CPython. Следует понимать, что действительное число не изменяется, а системы счисления просто по-разному его выражают.

Вопрос, какое число записано в строке "11" покажется странным, ведь для большинства очевидно, что это одиннадцать.

Однако в строке может быть представлено и другое число, в зависимости от системы счисления. Помимо десятичной, используются такие общепринятые альтернативы:

- Двоичная: с основой 2;

- Восьмеричная: с основой 8;

- Шестнадцатеричная (hex): с основой 16.

Что же мы подразумеваем, говоря что определённая система счисления имеет основу N?

Один из способов объяснения разных систем счисления заключается в том, чтобы представить, что у вас N пальцев.

Если же вам требуется более подробное объяснение систем счисления, обратитесь к книге Чарльза Петцольда «Код». В этой книге детально объясняются основы работы вычислительной техники.

Конструктор int() — один из способов показать, как разные системы счисления преобразуют одну и ту же строку с помощью Python. Если вы передадите str в int(), Python по умолчанию будет считать, что строка содержит число в десятичной системе. Однако вы можете дать другие указания:

>>> int('11')

11

>>> int('11', base=10) # 10 установлено по умолчанию

11

>>> int('11', base=2) # Двоичная

3

>>> int('11', base=8) # Восьмеричная

9

>>> int('11', base=16) # Шестнадцатеричная

17Чаще в Python для обозначения того, что целое число представлено в системе счисления, отличной от десятичной, используют префиксы-литералы. Для каждой из трёх альтернативных систем существует свой литерал.

| Тип литерала | Префикс | Пример |

|---|---|---|

| Нет | Нет | 11 |

| Binary literal | 0b или 0B |

0b11 |

| Octal literal | 0o или 0O |

0o11 |

| Hex literal | 0x или 0X |

0x11 |

Всё это — разновидности целочисленных литералов. Результаты применения префиксов будут такими же, как и в случае использования int() с определением параметра base. Для Python всё это просто целые числа:

>>> 11

11

>>> 0b11 # Двоичный литерал

3

>>> 0o11 # Восьмеричный литерал

9

>>> 0x11 # Шестнадцатеричный литерал

17В таблице ниже отражено, как можно ввести десятичные числа от 0 до 20 в двоичном, восьмеричном и шестнадцатеричном эквиваленте. Любой из этих способов можно использовать как в оболочке интерпретатора Python, так и в исходном коде, и все эти числа будут рассматриваться как относящиеся к типу int.

| Десятичные | Двоичные | Восмеричные | Шестнадцатеричные |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

0b0 |

0o0 |

0x0 |

1 |

0b1 |

0o1 |

0x1 |

2 |

0b10 |

0o2 |

0x2 |

3 |

0b11 |

0o3 |

0x3 |

4 |

0b100 |

0o4 |

0x4 |

5 |

0b101 |

0o5 |

0x5 |

6 |

0b110 |

0o6 |

0x6 |

7 |

0b111 |

0o7 |

0x7 |

8 |

0b1000 |

0o10 |

0x8 |

9 |

0b1001 |

0o11 |

0x9 |

10 |

0b1010 |

0o12 |

0xa |

11 |

0b1011 |

0o13 |

0xb |

12 |

0b1100 |

0o14 |

0xc |

13 |

0b1101 |

0o15 |

0xd |

14 |

0b1110 |

0o16 |

0xe |

15 |

0b1111 |

0o17 |

0xf |

16 |

0b10000 |

0o20 |

0x10 |

17 |

0b10001 |

0o21 |

0x11 |

18 |

0b10010 |

0o22 |

0x12 |

19 |

0b10011 |

0o23 |

0x13 |

20 |

0b10100 |

0o24 |

0x14 |

Кстати, вы можете сами убедиться, что подобные способы записи чисел очень часто используется в Стандартной Библиотеке Python. Найдите папку lib/python3.7/ в своей системе, перейдите в неё и введите команду:

$ grep -nri --include "*.py" -e "b0x" lib/python3.7Команда сработает в любой Unix-системе с утилитой grep. С её помощью вы найдёте все шестнадцатеричные литералы. Для поиска двоичных используйте b0b, а для восьмеричных — b0o.

Для чего же нужны альтернативные литералы целых чисел? Если коротко, числа 2, 8 и 16, в отличие от 10, являются степенями двойки. Основанные на них системы счисления выражают численные значения способами, более удобными для обработки бинарными вычислительными устройствами. К примеру, 65536, или 216, в шестнадцатеричной системе просто 10000 или, используя литерал, 0x10000.

Введение в Юникод

Как видите, проблема ASCII в том, что этой таблицы недостаточно для отображения знаков, символов и глифов, использующихся во всех языках и диалектах мира. Её недостаточно даже для английского языка.

Юникод служит тем же целям, что и ASCII, но содержит намного больший набор кодовых точек. В период времени между появлением ASCII и принятием Юникода использовалось ещё несколько различных кодировок, но рассматривать их подробно нет смысла, так как Юникод и одна из его схем, UTF-8, в настоящее время стали использоваться практически повсеместно.

Вы можете представить Юникод как расширенную версию ASCII-таблицы — с 1 114 112 возможными кодовыми точками, от 0 до 1 114 111. Это 17*(216) или 0x10ffff в шестнадцатеричном представлении. Фактически, ASCII является частью Юникода, так как первые 128 символов этих кодировок полностью совпадают.

Чтобы соблюсти технические детали, сам по себе Юникод не является кодировкой. Он скорее реализуется в различных кодировках символов, как вы вскоре увидите. По структуре Юникод скорее ассоциативный массив (что-то вроде dict) или база данных, состоящая из таблицы с двумя колонками. В этой таблице разные символы (такие как "a", "¢", или даже "ቈ") соотносятся с различными целыми положительными числами. Кодировка же должна предоставлять несколько больше возможностей.

Юникод содержит практически любой символ, который только можно представить, включая дополнительные непечатаемые. Например, кодовая точка 8207 соответствует отметке RTL, которая используется для смены направления письма. Она полезна в текстах, где абзацы на одном из европейских языков соседствуют с абзацами на арабских языках.

Прим. Кстати, если уж мы хотим быть совсем точны в деталях, то надо отметить ещё один факт. Исторически сложилось, что в Юникоде доступны только 1 111 998 кодовых точек.

Юникод и UTF-8

Довольно скоро стало понятно, что все необходимые символы невозможно вместить в таблицу, используя только один байт. Современные, более ёмкие кодировки требовали использования больших объёмов.

Ранее мы упоминали, что Юникод сам по себе не является кодировкой. И вот почему.

Юникод не содержит указаний по извлечению из текста бит, он работает только с кодовыми точками. В нём нет стандарта конверсии текста в двоичные данные и обратно.

Юникод является абстрактным стандартом кодировки. Для практического его применения чаще всего используют схему UTF-8. Стандарт Юникод (таблица соответствий символов кодовыми точкам) определяет несколько различных кодировок на основе единого набора символов.

Как и менее распространённые UTF-16 и UTF-32, UTF-8 — формат кодировки для отображения символов Юникода в двоичном виде, используя один или несколько байт на один символ. UTF-16 и UTF-32 мы обсудим чуть позже, но пока нам интересен UTF-8 как самый популярный формат.

Сначала требуется разобрать термины «кодирование» и «декодирование».

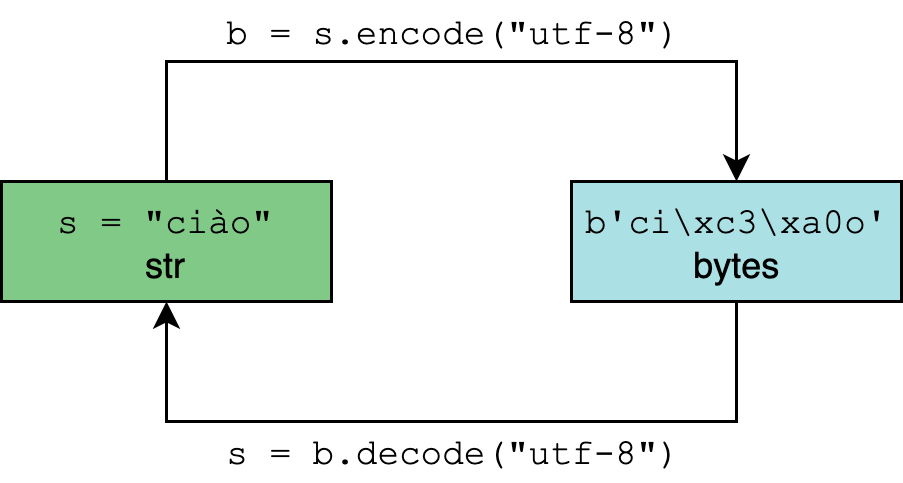

Кодирование и декодирование в Python 3

Тип данных str в Python 3 рассчитан на представление текста в удобном для чтения формате и может содержать любые символы Юникода.

Тип bytes, напротив, представляет двоичные данные, последовательность байт, без указания на кодировку.

Кодирование и декодирование — это процесс перехода данных из одной формы в другую.

В методах .encode() и .decode() по умолчанию используется параметр "utf-8", однако для большей уверенности этот параметр можно определить самостоятельно:

>>> "résumé".encode("utf-8")

b'rxc3xa9sumxc3xa9'

>>> "El Niño".encode("utf-8")

b'El Nixc3xb1o'

>>> b"rxc3xa9sumxc3xa9".decode("utf-8")

'résumé'

>>> b"El Nixc3xb1o".decode("utf-8")

'El Niño'str.encode() возвращает объект типа bytes. И литералы этого типа объектов (такие как b"rxc3xa9sumxc3xa9"), и его отображение допускают только символы ASCII.

Вот почему при вызове "El Niño".encode("utf-8"), ASCII-совместимое "El" отображается как есть, а n с тильдой экранируется в "xc3xb1". Этой с виду неудобочитаемой последовательностью представлены два байта, 0xc3 и 0xb1 в шестнадцатеричной системе:

>>> " ".join(f"{i:08b}" for i in (0xc3, 0xb1))

'11000011 10110001'Таким образом символ ñ требует два байта для бинарного представления с помощью UTF-8.

Прим. Если вы введёте help(str.encode), скорее всего, увидите параметр по умолчанию encoding='utf-8'. Однако имейте в виду, что настройки Windows для Python 3.6 могут отличаться, поэтому использовать методы кодирования и декодирования без указания необходимой кодировки (например "résumé".encode()) следует с осторожностью.

Python 3: всё на Юникоде

Python 3 полностью реализован на Юникоде, а точнее на UTF-8. Вот что это означает:

- По умолчанию предполагается, что исходный код Python 3 написан с помощью UTF-8. Это значит, что вам не нужно использовать определение

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-в начале файлов.pyв этой версии языка. - Все тексты (объекты формата

str) реализованы на Юникоде. Кодированный текст представлен двоичными данными (bytes). Типstrможет содержать любой символ-литерал из Юникода (например"Δv / Δt"), и все они хранятся в Юникоде. - Любой из символов Юникода приемлем в качестве идентификатора. Например, вы можете использовать выражение

résumé = "~/Documents/resume.pdf". - В модуле

reпо умолчанию установлен флагre.UNICODE, а неre.ASCII. Это означает, чтоr"w"соответствует буквам из Юникода, а не просто символам ASCII. - По умолчанию

encodingвstr.encode()вbytes.decode()установлен в UTF-8.

Нужно отметить также нюанс, касающийся встроенного метода open(). Его параметр encoding зависит от платформы и определяется значением locale.getpreferredencoding():

>>> # Mac OS X High Sierra

>>> import locale

>>> locale.getpreferredencoding()

'UTF-8'

>>> # Windows Server 2012; другие сборки Windows могут использовать UTF-16

>>> import locale

>>> locale.getpreferredencoding()

'cp1252'Мы делаем упор на эти моменты, чтобы вы вдруг не подумали, что кодировка UTF-8 является универсальной. Она действительно широко распространена, но вы вполне можете столкнуться и с другими вариантами. Не будет лишним предусмотреть это в коде.

Один байт, два байта, три байта, четыре…

Одна из важнейших особенностей UTF-8 состоит в том, что это кодировка с переменным размером.

Вспомните раздел, посвящённый ASCII. Любой символ в этой таблице требует максимум одного байта пространства. Это можно быстро проверить с помощью следующего генератора:

>>> all(len(chr(i).encode("ascii")) == 1 for i in range(128))

TrueС UTF-8 дела обстоят по-другому. Символы Юникода могут занимать от одного до четырёх байт. Вот пример четырёхбайтного символа:

>>> ibrow = "?"

>>> len(ibrow)

1

>>> ibrow.encode("utf-8")

b'xf0x9fxa4xa8'

>>> len(ibrow.encode("utf-8"))

4

>>> # Вызов list() с объектом типа bytes возвращает

>>> # значение каждого байта

>>> list(b'xf0x9fxa4xa8')

[240, 159, 164, 168]Это небольшая, но важная особенность метода len():

- Размер единичного символа Юникода в объекте

strязыка Python всегда будет равен 1, вне зависимости от количества занимаемых байт. - Длина того же символа в объекте типа

bytesбудет варьироваться от 1 до 4.

Таблица ниже показывает, сколько байт занимают основные типы символов.

| Десятичный диапазон | Шестнадцатеричный диапазон |

Включённые символы | Примеры |

|---|---|---|---|

| от 0 до 127 | от "u0000" до "u007F" |

U.S. ASCII | "A", "n", "7", "&" |

| от 128 до 2047 | от "u0080" до "u07FF" |

Большая часть латинских алфавитов* | "ę", "±", "ƌ", "ñ" |

| от 2048 до 65535 | от "u0800" до "uFFFF" |

Дополнительные части многоязыковых символов (BMP)** | "ത", "ᄇ", "ᮈ", "‰" |

| от 65536 до 1114111 | от "U00010000" до "U0010FFFF" |

Другое*** | "?", "?", "?", "?", |

*Такие как английский, арабский, греческий, ирландский.

**Масса языков и символов, в основном китайский, японский и корейский с разделением по томам (а также ASCII и латиница).

***Дополнительные символы китайского, японского, корейского и вьетнамского, а также другие символы и эмоджи.

Прим. У UTF-8 есть и другие технические особенности. Те, кто работает на Python, редко с ними сталкиваются, поэтому мы не будем раскрывать их в этой статье, но упомянем вкратце, чтобы сохранить полноту картины. Так, UTF-8 использует коды-префиксы, указывающие на количество байт в последовательности. Такой приём позволяет декодеру группировать байты в условиях кодировки с переменным размером. Количество байт в последовательности определяется первым её байтом. Другие технические подробности можно найти на странице Википедии, посвящённой UTF-8 или на официальном сайте.

Особенности UTF-16 и UTF-32

Рассмотрим альтернативные кодировки, UTF-16 и UTF-32. Различие между ними и UTF-8 в основном практическое. Продемонстрируем величину расхождения с помощью перевода туда и обратно:

>>> letters = "αβγδ"

>>> rawdata = letters.encode("utf-8")

>>> rawdata.decode("utf-8")

'αβγδ'

>>> rawdata.decode("utf-16") # ?

'뇎닎돎듎'В данном случае, когда мы кодируем четыре буквы греческого алфавита в двоичные данные с помощью UTF-8, а декодируем обратно в текст с использованием UTF-16, на выходе получается строка с совершенно другими символами (из корейского алфавита).

Так происходит, если для кодирования и декодирования применяют разные кодировки. Два варианта декодирования одного бинарного объекта могут вернуть текст даже на другом языке.

Таблица ниже демонстрирует количество байт, используемых в разных кодировках:

| Кодировка | Байт на символ (включительно) | Варьируемая длина |

|---|---|---|

| UTF-8 | От 1 до 4 | Да |

| UTF-16 | От 2 до 4 | Да |

| UTF-32 | 4 | Нет |

Любопытный аспект семейства UTF: UTF-8 не всегда занимает меньше памяти, чем UTF-16. Хотя с точки зрения математики это выглядит маловероятным, однако это возможно:

>>> text = "記者 鄭啟源 羅智堅"

>>> len(text.encode("utf-8"))

26

>>> len(text.encode("utf-16"))

22Так получается из-за того, что кодовые точки в диапазоне от U+0800 до U+FFFF (от 2048 до 65535 в десятичной системе) в кодировке UTF-8 занимают три байта, а в UTF-16 только два.

Это не означает, что нужно работать с UTF-16, независимо от того, насколько часто вы работаете с символами в этом диапазоне. Один из самых важных поводов придерживаться UTF-8 — в мире кодировок лучше держаться вместе с большинством.

Кроме того, в 2019 году компьютерная память стоит дёшево, и экономия четырёх байт за счёт использования нестандартной кодировки вряд ли стоит усилий.

Прим. перев. Есть и более весомые причины использовать UTF-8. Среди них её обратная совместимость с ASCII, а также то, что это самосинхронизирующаяся кодировка.

Вы освоили самую сложную часть статьи. Теперь посмотрим, как всё изученное реализуется на Python.

В Python есть несколько встроенных функций, каким-либо образом относящихся к системам счисления и кодировке:

ascii()bin()bytes()chr()hex()int()oct()ord()str()

Логически их можно сгруппировать по назначению.

ascii(),bin(),hex()иoct()предназначены для различного представления вводных данных. Все они возвращаютstr. Первая,ascii(), производит представление объекта в ASCII, экранируя не входящие в эту таблицу символы. Оставшиеся три дают соответственно двоичное, шестнадцатеричное и восьмеричное представление целого числа. Все эти функции меняют только представление объекта, не изменяя непосредственно вводные данные.bytes(),str()иint()— конструкторы классов соответствующих типов:bytes,str, иint. Все они предлагают способы подогнать данные под желаемый тип.ord()иchr()выполняют противоположные действия.ord()конвертирует символ в десятичную кодовую точку, аchr()принимает в качестве аргумента целое число, и возвращает символ, кодовой точкой которого это число является.

В таблице ниже эти функции разобраны более подробно:

| Функция | Форма | Тип аргументов | Тип возвращаемых данных | Назначение |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ascii() |

ascii(obj) |

Различный | str |

Представление объекта символами ASCII. Не входящие в таблицу символы экранируются |

bin() |

bin(number) |

number: int |

str |

Бинарное представление целого чиста с префиксом "0b" |

bytes() |

bytes(последовательность_целых_чисел)

|

Различный | bytes |

Приводит аргумент к двоичным данным, типу bytes |

chr() |

chr(i) |

i: int

|

str |

Преобразует кодовую точку (целочисленное значение) в символ Юникода |

hex() |

hex(number) |

number: int |

str |

Шестнадцатеричное представление целого числа с префиксом "0x" |

int() |

int([x])

|

Различный | int |

Приводит аргумент к типу int |

oct() |

oct(number) |

number: int |

str |

Восьмеричное представление целого числа с префиксом "0o" |

ord() |

ord(c) |

c: str

|

int |

Возвращает значение кодовой точки символа Юникода |

str() |

str(object=’‘)

|

Различный | str |

Приводит аргумент к текстовому представлению, типу str |

Дальше можно посмотреть полезные примеры использования этих функций.

ascii():

>>> ascii("abcdefg")

"'abcdefg'"

>>> ascii("jalepeño")

"'jalepe\xf1o'"

>>> ascii((1, 2, 3))

'(1, 2, 3)'

>>> ascii(0xc0ffee) # Шестнадцатеричный литерал (int)

'12648430'bin():

>>> bin(0)

'0b0'

>>> bin(400)

'0b110010000'

>>> bin(0xc0ffee) # Шестнадцатеричный литерал (int)

'0b110000001111111111101110'

>>> [bin(i) for i in [1, 2, 4, 8, 16]] # `int` + обработка списка

['0b1', '0b10', '0b100', '0b1000', '0b10000']bytes():

>>> # Последовательность целых чисел

>>> bytes((104, 101, 108, 108, 111, 32, 119, 111, 114, 108, 100))

b'hello world'

>>> bytes(range(97, 123)) # Последовательность целых чисел

b'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

>>> bytes("real ?", "utf-8") # Строка + кодировка

b'real xf0x9fx90x8d'

>>> bytes(10)

b'x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00'

>>> bytes.fromhex('c0 ff ee')

b'xc0xffxee'

>>> bytes.fromhex("72 65 61 6c 70 79 74 68 6f 6e")

b'realpython'chr():

>>> chr(97)

'a'

>>> chr(7048)

'ᮈ'

>>> chr(1114111)

'U0010ffff'

>>> chr(0x10FFFF) # Шестнадцатеричный литерал (int)

'U0010ffff'

>>> chr(0b01100100) # Двоичный литерал (int)

'd'hex():

>>> hex(100)

'0x64'

>>> [hex(i) for i in [1, 2, 4, 8, 16]]

['0x1', '0x2', '0x4', '0x8', '0x10']

>>> [hex(i) for i in range(16)]

['0x0', '0x1', '0x2', '0x3', '0x4', '0x5', '0x6', '0x7',

'0x8', '0x9', '0xa', '0xb', '0xc', '0xd', '0xe', '0xf']int():

>>> int(11.0)

11

>>> int('11')

11

>>> int('11', base=2)

3

>>> int('11', base=8)

9

>>> int('11', base=16)

17

>>> int(0xc0ffee - 1.0)

12648429

>>> int.from_bytes(b"x0f", "little")

15

>>> int.from_bytes(b'xc0xffxee', "big")

12648430oct():

>>> ord("a")

97

>>> ord("ę")

281

>>> ord("ᮈ")

7048

>>> [ord(i) for i in "hello world"]

[104, 101, 108, 108, 111, 32, 119, 111, 114, 108, 100]str():

>>> str("str of string")

'str of string'

>>> str(5)

'5'

>>> str([1, 2, 3, 4]) # Like [1, 2, 3, 4].__str__(), but use str()

'[1, 2, 3, 4]'

>>> str(b"xc2xbc cup of flour", "utf-8")

'¼ cup of flour'

>>> str(0xc0ffee)

'12648430'Литералы для строк на Python

Вместо использования конструктора str(), объект этого типа чаще вводят напрямую:

>>> meal = "shrimp and grits"Выглядит достаточно просто. Но есть один аспект, о котором нужно помнить. Поскольку Python позволяет использовать все возможности Юникода, можно «напечатать» символы, которых вы никогда не найдёте на клавиатуре. Можно скопировать и вставить их прямо в оболочку интерпретатора:

>>> alphabet = 'αβγδεζηθικλμνξοπρςστυφχψ'

>>> print(alphabet)

αβγδεζηθικλμνξοπρςστυφχψКроме ввода через консоль реальных, неэкранированых символов Юникода, существуют и другие способы ввода текстовых строк.

Самые насыщенные разделы документации Python посвящены лексическому анализу. В частности, раздел о строках и литералах. Возможно, для понимания данного аспекта языка этот раздел придётся неоднократно перечитать.

Кроме прочего, там говорится о шести возможных способах ввода одного символа Юникода.

Первый, и самый распространённый метод, как вы уже видели — прямой ввод. Проблема состоит в поиске необходимых сочетаний клавиш. Здесь и могут пригодиться другие способы получения и представления символов. Вот полный список:

| Экранирующая последовательность | Значение | Как отобразить "a" |

|---|---|---|

"ooo" |

Символ с восьмеричным значением ooo |

"141" |

"xhh" |

Символ с шестнадцатеричным значением hh |

"x61" |

"N{name}" |

Символ с именем name в базе данных Юникода |

"N{LATIN SMALL LETTER A}" |

"uxxxx" |

Символ с шестнадцатибитным (двухбайтным) шестнадцатеричным значением xxxx |

"u0061" |

"Uxxxxxxxx" |

Символ с тридцатидвухбитным (четырёхбайтным) шестнадцатеричным значением xxxxxxxx |

"U00000061" |

Это соответствие можно проверить на практике:

>>> (

... "a" ==

... "x61" ==

... "N{LATIN SMALL LETTER A}" ==

... "u0061" ==

... "U00000061"

... )

TrueНужно однако упомянуть и два основных затруднения при использовании этих методов:

- Не каждый способ работает со всеми символами. Шестнадцатеричное представление числа 300 выглядит как

0x012c, а это значение просто не поместится в экранирующий код"xhh", так как в нём допускаются всего две цифры. Самая большая кодовая точка, которую можно втиснуть в этот формат —"xff"("ÿ"). Аналогичо"ooo"можно использовать только до"777"("ǿ"). - Для

xhh,uxxxx, иUxxxxxxxxтребуется вводить ровно столько цифр, сколько указано в примерах. Это может стать неприятным сюрпризом, поскольку обычно основанные на Юникоде таблицы содержат кодовые точки для символов с префиксомU+и варьирующимся количеством шестнадцатеричных символов. В этих таблицах кодовые точки отображают только значимые цифры.

Например, если вы обратитесь к сайту unicode-table.com с целью получить данные готического символа faihu (или fehu), "?", его кодовая точка будет U+10346.

Как же можно разместить его в "uxxxx" или "Uxxxxxxxx"? В "uxxxx" эту кодовую точку вместить невозможно, поскольку она соответствует четырёхбайтному символу. А чтобы представить его в "Uxxxxxxxx", придётся выровнять последовательность с левой стороны:

>>> "U00010346"

'?'Это также значит, что экранирующая последовательность "Uxxxxxxxx" — единственная последовательность, способная вместить любой символ Юникода.

Прим. Вот код небольшой, но удобной функции, переводящей записи типа "U+10346" в приемлемый для Python формат с помощью str.zfill():

>>> def make_uchr(code: str):

... return chr(int(code.lstrip("U+").zfill(8), 16))

>>> make_uchr("U+10346")

'?'

>>> make_uchr("U+0026")

'&'Другие поддерживаемые Python кодировки

Пока что мы рассказали про 4 разные кодировки символов:

- ASCII;

- UTF-8;

- UTF-16;

- UTF-32.

Однако существует большое количество и других вариантов кодировки.

Один из примеров — Latin-1 (другое название ISO-8859-1). Это базовая кодировка для Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) в спецификации RFC 2616. Для Windows существует собственный вариант Latin-1, который называется cp1252.

Прим. Кодировка ISO-8859-1 всё ещё широко используется. Библиотека requests неукоснительно придерживается спецификации RFC 2616, используя её по умолчанию для содержимого отзывов HTTP/HTTPS. Если в заголовке Content-Type находится слово «text» и не выбрана другая кодировка, requests использует ISO-8859-1.

Полный список допустимых кодировок можно найти в документации модуля codecs, входящего в набор стандартных библиотек Python.

Среди этих кодировок стоит упомянуть ещё одну, зачастую весьма полезную. Это "unicode-escape". Если вы декодировали str и хотите быстро получить представление содержащихся в ней экранированных литералов Юникода, можно определить эту кодировку в .encode:

>>> alef = chr(1575) # Или "u0627"

>>> alef_hamza = chr(1571) # Или "u0623"

>>> alef, alef_hamza

('ا', 'أ')

>>> alef.encode("unicode-escape")

b'\u0627'

>>> alef_hamza.encode("unicode-escape")

b'\u0623'Вы знаете, что говорят насчёт предположений…

Хотя Python по умолчанию предполагает, что файлы и код созданы на основе кодировки UTF-8, вам, как программисту, не следует делать аналогичное предположение относительно сторонних данных.

Когда вы получаете данные в двоичном коде из внешних источников, из файла или по сетевому соединению, стоит проверить, указана ли кодировка. Если нет — вы можете уточнить.

Все операции ввода-вывода осуществляют в байтах, наборе нулей и единиц, пока вы не сообщите системе кодировку для преобразования этих данных в текст.

Приведём пример того, что может пойти не так. Допустим, вы подписаны на API, который передаёт вам рецепт блюда дня. Вы получаете его в формате bytes и раньше всегда без проблем декодировали с использованием .decode("utf-8") . Но именно в этот день часть рецепта выглядела так:

>>> data = b"xbc cup of flour"Похоже, нам потребуется мука, но сколько?

>>> data.decode("utf-8")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "", line 1, in

UnicodeDecodeError: 'utf-8' codec can't decode byte 0xbc in position 0: invalid start byteА вот и та самая неприятная ошибка UnicodeDecodeError. Подобное вполне может произойти, когда вы делаете предположение об используемой кодировке. Уточняем у разработчика ресурса, предоставляющего API. Выясняется, что полученный вами файл был закодирован с помощью Latin-1:

>>> data.decode("latin-1")

'¼ cup of flour'Именно в этом и крылась проблема. В Latin-1 каждый символ кодируется одним байтом, в вот в UTF-8 символ «¼» требует два байта ("xc2xbc").

Как видите, делать предположения относительно кодировки полученных данных довольно рискованно. Обычно это UTF-8, однако в тех случаях, когда это не так, у вас могут возникнуть проблемы.

Если уж у вас нет другого выхода и кодировку приходится угадывать, обратите внимание на библиотеку chardet. В ней используются разработанные в Mozilla методы, позволяющие сделать обоснованное предположение насчёт кодировки данных. Однако учтите, что такие инструменты должны быть вашим последним средством, не стоит прибегать к ним, если есть возможность решить вопрос другим способом.

Всякая всячина: unicodedata

Нельзя не упомянуть также модуль unicodedata. Он позволяет взаимодействовать с базой данных символов Юникода (Unicode Character Database, UCD).

>>> import unicodedata

>>> unicodedata.name("€")

'EURO SIGN'

>>> unicodedata.lookup("EURO SIGN")

'€'Подводим итоги

Итак, в этой статье вы познакомились со следующими концепциями кодировки символов в Python:

- Фундаментальные принципы кодировки символов и систем счисления;

- Целочисленные, двоичные, восьмеричные, шестнадцатеричные, строковые и байтовые литералы в Python;

- Встроенные функции языка, работающие с кодировкой и системами счисления;

- Особенности обработки текстовых и двоичных данных.

Дополнительные источники

Ещё больше информации можно получить из следующих материалов (на английском языке):

- UTF-8 Everywhere Manifesto.

- Joel Spolsky: Минимальный уровень знаний о Юникоде и наборах символов, требующийся каждому разработчику ПО (Без отговорок!).

- David Zentgraf: Что обязательно должен знать о кодировках и наборах символов каждый программист для работы с текстом.

- Mozilla: Комплексный подход к определению языков и кодировок.

- Wikipedia.

- John Skeet: Юникод и .NET.

- Network Working Group, RFC 3629: UTF-8, формат преобразования ISO 10646.

- Unicode Technical Standard #18: Регулярные выражения Юникода.

В документации языка нашему вопросу посвящены два раздела:

- What’s New in Python 3.0;

- Unicode HOWTO.

Перевод статьи Unicode & Character Encodings in Python: A Painless Guide

What is a Unicode encoding?

Unicode is the encoding type or standard which contains the character set of all the languages that exist all around the globe. Each character is mapped to an integer known as a Code point. It uniquely identifies a character among the other characters.

The Unicode encoding came into existence when languages other than English started getting used prominently.

Advantage of using a Unicode encoding

The biggest advantage with Unicode is, it allows the use of different encoding and more diverse characters set with the same set of code points.

This makes easy for the developers from different part of the world to choose the among the characters of their choice without worrying much about the encoding.

How to get the Unicode code of a character in Python?

In Python, we have a few utility functions to work with Unicode. Let’s see how we can leverage them.

Approach 1: Using built-in ord() function

ord() function came into existence only for this purpose, it returns the Unicode code of a character passed to it.

ord(l) – Returns an integer representing the Unicode code of the character l.

How to return the Unicode code of a character using ord() ?

print(ord(u"$")) # Unicode code of $ character #Output #36 print(ord(u"v")) # Unicode code of v character #Output #118 print(ord(u"⁹")) # Unicode code of superscript 9 #Output #8313 print(ord(u"₅")) # Unicode code of subscript 5 #Output #8325 print(ord(u"ल")) # Unicode code of devnagri letter 'ल' #Output #2354

The u prefix before the string tells us that the string is a Unicode string. Since python 3 release, it is not necessary to write the prefix u as all the string by default are Unicode string.

Bonus:

The method chr() is the inverse of the method ord(). chr() gets the character that a Unicode code point corresponds to.

Example:

print(chr(554)) # Get the character from unicode code 554 #Output #Ȫ print(chr(728)) # Get the character from unicode code 728 #Output #˘ print(chr(900)) # Get the character from unicode code 900 #Output #΄ print(chr(1121)) # Get the character from unicode code 1121 #Output #ѡ

That’s all, folks !!!

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Unicode in Python: Working With Character Encodings

Handling character encodings in Python or any other language can at times seem painful. Places such as Stack Overflow have thousands of questions stemming from confusion over exceptions like UnicodeDecodeError and UnicodeEncodeError. This tutorial is designed to clear the Exception fog and illustrate that working with text and binary data in Python 3 can be a smooth experience. Python’s Unicode support is strong and robust, but it takes some time to master.

This tutorial is different because it’s not language-agnostic but instead deliberately Python-centric. You’ll still get a language-agnostic primer, but you’ll then dive into illustrations in Python, with text-heavy paragraphs kept to a minimum. You’ll see how to use concepts of character encodings in live Python code.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll:

- Get conceptual overviews on character encodings and numbering systems

- Understand how encoding comes into play with Python’s

strandbytes - Know about support in Python for numbering systems through its various forms of

intliterals - Be familiar with Python’s built-in functions related to character encodings and numbering systems

Character encoding and numbering systems are so closely connected that they need to be covered in the same tutorial or else the treatment of either would be totally inadequate.

What’s a Character Encoding?

There are tens if not hundreds of character encodings. The best way to start understanding what they are is to cover one of the simplest character encodings, ASCII.

Whether you’re self-taught or have a formal computer science background, chances are you’ve seen an ASCII table once or twice. ASCII is a good place to start learning about character encoding because it is a small and contained encoding. (Too small, as it turns out.)

It encompasses the following:

- Lowercase English letters: a through z

- Uppercase English letters: A through Z

- Some punctuation and symbols:

"$"and"!", to name a couple - Whitespace characters: an actual space (

" "), as well as a newline, carriage return, horizontal tab, vertical tab, and a few others - Some non-printable characters: characters such as backspace,

"b", that can’t be printed literally in the way that the letter A can

So what is a more formal definition of a character encoding?

At a very high level, it’s a way of translating characters (such as letters, punctuation, symbols, whitespace, and control characters) to integers and ultimately to bits. Each character can be encoded to a unique sequence of bits. Don’t worry if you’re shaky on the concept of bits, because we’ll get to them shortly.

The various categories outlined represent groups of characters. Each single character has a corresponding code point, which you can think of as just an integer. Characters are segmented into different ranges within the ASCII table:

| Code Point Range | Class |

|---|---|

| 0 through 31 | Control/non-printable characters |

| 32 through 64 | Punctuation, symbols, numbers, and space |

| 65 through 90 | Uppercase English alphabet letters |

| 91 through 96 | Additional graphemes, such as [ and |

| 97 through 122 | Lowercase English alphabet letters |

| 123 through 126 | Additional graphemes, such as { and | |

| 127 | Control/non-printable character (DEL) |

The entire ASCII table contains 128 characters. This table captures the complete character set that ASCII permits. If you don’t see a character here, then you simply can’t express it as printed text under the ASCII encoding scheme.

| Code Point | Character (Name) | Code Point | Character (Name) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NUL (Null) | 64 | @ |

| 1 | SOH (Start of Heading) | 65 | A |

| 2 | STX (Start of Text) | 66 | B |

| 3 | ETX (End of Text) | 67 | C |

| 4 | EOT (End of Transmission) | 68 | D |

| 5 | ENQ (Enquiry) | 69 | E |

| 6 | ACK (Acknowledgment) | 70 | F |

| 7 | BEL (Bell) | 71 | G |

| 8 | BS (Backspace) | 72 | H |

| 9 | HT (Horizontal Tab) | 73 | I |

| 10 | LF (Line Feed) | 74 | J |

| 11 | VT (Vertical Tab) | 75 | K |

| 12 | FF (Form Feed) | 76 | L |

| 13 | CR (Carriage Return) | 77 | M |

| 14 | SO (Shift Out) | 78 | N |

| 15 | SI (Shift In) | 79 | O |

| 16 | DLE (Data Link Escape) | 80 | P |

| 17 | DC1 (Device Control 1) | 81 | Q |

| 18 | DC2 (Device Control 2) | 82 | R |

| 19 | DC3 (Device Control 3) | 83 | S |

| 20 | DC4 (Device Control 4) | 84 | T |

| 21 | NAK (Negative Acknowledgment) | 85 | U |

| 22 | SYN (Synchronous Idle) | 86 | V |

| 23 | ETB (End of Transmission Block) | 87 | W |

| 24 | CAN (Cancel) | 88 | X |

| 25 | EM (End of Medium) | 89 | Y |

| 26 | SUB (Substitute) | 90 | Z |

| 27 | ESC (Escape) | 91 | [ |

| 28 | FS (File Separator) | 92 | |

| 29 | GS (Group Separator) | 93 | ] |

| 30 | RS (Record Separator) | 94 | ^ |

| 31 | US (Unit Separator) | 95 | _ |

| 32 | SP (Space) | 96 | ` |

| 33 | ! |

97 | a |

| 34 | " |

98 | b |

| 35 | # |

99 | c |

| 36 | $ |

100 | d |

| 37 | % |

101 | e |

| 38 | & |

102 | f |

| 39 | ' |

103 | g |

| 40 | ( |

104 | h |

| 41 | ) |

105 | i |

| 42 | * |

106 | j |

| 43 | + |

107 | k |

| 44 | , |

108 | l |

| 45 | - |

109 | m |

| 46 | . |

110 | n |

| 47 | / |

111 | o |

| 48 | 0 |

112 | p |

| 49 | 1 |

113 | q |

| 50 | 2 |

114 | r |

| 51 | 3 |

115 | s |

| 52 | 4 |

116 | t |

| 53 | 5 |

117 | u |

| 54 | 6 |

118 | v |

| 55 | 7 |

119 | w |

| 56 | 8 |

120 | x |

| 57 | 9 |

121 | y |

| 58 | : |

122 | z |

| 59 | ; |

123 | { |

| 60 | < |

124 | | |

| 61 | = |

125 | } |

| 62 | > |

126 | ~ |

| 63 | ? |

127 | DEL (delete) |

The string Module

Python’s string module is a convenient one-stop-shop for string constants that fall in ASCII’s character set.

Here’s the core of the module in all its glory:

# From lib/python3.7/string.py

whitespace = ' tnrvf'

ascii_lowercase = 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'

ascii_uppercase = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

ascii_letters = ascii_lowercase + ascii_uppercase

digits = '0123456789'

hexdigits = digits + 'abcdef' + 'ABCDEF'

octdigits = '01234567'

punctuation = r"""!"#$%&'()*+,-./:;<=>?@[]^_`{|}~"""

printable = digits + ascii_letters + punctuation + whitespace

Most of these constants should be self-documenting in their identifier name. We’ll cover what hexdigits and octdigits are shortly.

You can use these constants for everyday string manipulation:

>>>

>>> import string

>>> s = "What's wrong with ASCII?!?!?"

>>> s.rstrip(string.punctuation)

'What's wrong with ASCII'

A Bit of a Refresher

Now is a good time for a short refresher on the bit, the most fundamental unit of information that a computer knows.

A bit is a signal that has only two possible states. There are different ways of symbolically representing a bit that all mean the same thing:

- 0 or 1

- “yes” or “no”

TrueorFalse- “on” or “off”

Our ASCII table from the previous section uses what you and I would just call numbers (0 through 127), but what are more precisely called numbers in base 10 (decimal).

You can also express each of these base-10 numbers with a sequence of bits (base 2). Here are the binary versions of 0 through 10 in decimal:

| Decimal | Binary (Compact) | Binary (Padded Form) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 00000000 |

| 1 | 1 | 00000001 |

| 2 | 10 | 00000010 |

| 3 | 11 | 00000011 |

| 4 | 100 | 00000100 |

| 5 | 101 | 00000101 |

| 6 | 110 | 00000110 |

| 7 | 111 | 00000111 |

| 8 | 1000 | 00001000 |

| 9 | 1001 | 00001001 |

| 10 | 1010 | 00001010 |

Notice that as the decimal number n increases, you need more significant bits to represent the character set up to and including that number.

Here’s a handy way to represent ASCII strings as sequences of bits in Python. Each character from the ASCII string gets pseudo-encoded into 8 bits, with spaces in between the 8-bit sequences that each represent a single character:

>>>

>>> def make_bitseq(s: str) -> str:

... if not s.isascii():

... raise ValueError("ASCII only allowed")

... return " ".join(f"{ord(i):08b}" for i in s)

>>> make_bitseq("bits")

'01100010 01101001 01110100 01110011'

>>> make_bitseq("CAPS")

'01000011 01000001 01010000 01010011'

>>> make_bitseq("$25.43")

'00100100 00110010 00110101 00101110 00110100 00110011'

>>> make_bitseq("~5")

'01111110 00110101'

The f-string f"{ord(i):08b}" uses Python’s Format Specification Mini-Language, which is a way of specifying formatting for replacement fields in format strings:

-

The left side of the colon,

ord(i), is the actual object whose value will be formatted and inserted into the output. Using the Pythonord()function gives you the base-10 code point for a singlestrcharacter. -

The right hand side of the colon is the format specifier.

08means width 8, 0 padded, and thebfunctions as a sign to output the resulting number in base 2 (binary).

This trick is mainly just for fun, and it will fail very badly for any character that you don’t see present in the ASCII table. We’ll discuss how other encodings fix this problem later on.

We Need More Bits!

There’s a critically important formula that’s related to the definition of a bit. Given a number of bits, n, the number of distinct possible values that can be represented in n bits is 2n:

def n_possible_values(nbits: int) -> int:

return 2 ** nbits

Here’s what that means:

- 1 bit will let you express 21 == 2 possible values.

- 8 bits will let you express 28 == 256 possible values.

- 64 bits will let you express 264 == 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 possible values.

There’s a corollary to this formula: given a range of distinct possible values, how can we find the number of bits, n, that is required for the range to be fully represented? What you’re trying to solve for is n in the equation 2n = x (where you already know x).

Here’s what that works out to:

>>>

>>> from math import ceil, log

>>> def n_bits_required(nvalues: int) -> int:

... return ceil(log(nvalues) / log(2))

>>> n_bits_required(256)

8

The reason that you need to use a ceiling in n_bits_required() is to account for values that are not clean powers of 2. Say you need to store a character set of 110 characters total. Naively, this should take log(110) / log(2) == 6.781 bits, but there’s no such thing as 0.781 bits. 110 values will require 7 bits, not 6, with the final slots being unneeded:

>>>

>>> n_bits_required(110)

7

All of this serves to prove one concept: ASCII is, strictly speaking, a 7-bit code. The ASCII table that you saw above contains 128 code points and characters, 0 through 127 inclusive. This requires 7 bits:

>>>

>>> n_bits_required(128) # 0 through 127

7

>>> n_possible_values(7)

128

The issue with this is that modern computers don’t store much of anything in 7-bit slots. They traffic in units of 8 bits, conventionally known as a byte.

This means that the storage space used by ASCII is half-empty. If it’s not clear why this is, think back to the decimal-to-binary table from above. You can express the numbers 0 and 1 with just 1 bit, or you can use 8 bits to express them as 00000000 and 00000001, respectively.

You can express the numbers 0 through 3 with just 2 bits, or 00 through 11, or you can use 8 bits to express them as 00000000, 00000001, 00000010, and 00000011, respectively. The highest ASCII code point, 127, requires only 7 significant bits.

Knowing this, you can see that make_bitseq() converts ASCII strings into a str representation of bytes, where every character consumes one byte:

>>>

>>> make_bitseq("bits")

'01100010 01101001 01110100 01110011'

ASCII’s underutilization of the 8-bit bytes offered by modern computers led to a family of conflicting, informalized encodings that each specified additional characters to be used with the remaining 128 available code points allowed in an 8-bit character encoding scheme.

Not only did these different encodings clash with each other, but each one of them was by itself still a grossly incomplete representation of the world’s characters, regardless of the fact that they made use of one additional bit.

Over the years, one character encoding mega-scheme came to rule them all. However, before we get there, let’s talk for a minute about numbering systems, which are a fundamental underpinning of character encoding schemes.

Covering All the Bases: Other Number Systems

In the discussion of ASCII above, you saw that each character maps to an integer in the range 0 through 127.

This range of numbers is expressed in decimal (base 10). It’s the way that you, me, and the rest of us humans are used to counting, for no reason more complicated than that we have 10 fingers.

But there are other numbering systems as well that are especially prevalent throughout the CPython source code. While the “underlying number” is the same, all numbering systems are just different ways of expressing the same number.

If I asked you what number the string "11" represents, you’d be right to give me a strange look before answering that it represents eleven.

However, this string representation can express different underlying numbers in different numbering systems. In addition to decimal, the alternatives include the following common numbering systems:

- Binary: base 2

- Octal: base 8

- Hexadecimal (hex): base 16

But what does it mean for us to say that, in a certain numbering system, numbers are represented in base N?

Here is the best way that I know of to articulate what this means: it’s the number of fingers that you’d count on in that system.

If you want a much fuller but still gentle introduction to numbering systems, Charles Petzold’s Code is an incredibly cool book that explores the foundations of computer code in detail.

One way to demonstrate how different numbering systems interpret the same thing is with Python’s int() constructor. If you pass a str to int(), Python will assume by default that the string expresses a number in base 10 unless you tell it otherwise:

>>>

>>> int('11')

11

>>> int('11', base=10) # 10 is already default

11

>>> int('11', base=2) # Binary

3

>>> int('11', base=8) # Octal

9

>>> int('11', base=16) # Hex

17

There’s a more common way of telling Python that your integer is typed in a base other than 10. Python accepts literal forms of each of the 3 alternative numbering systems above:

| Type of Literal | Prefix | Example |

|---|---|---|

| n/a | n/a | 11 |

| Binary literal | 0b or 0B |

0b11 |

| Octal literal | 0o or 0O |

0o11 |

| Hex literal | 0x or 0X |

0x11 |

All of these are sub-forms of integer literals. You can see that these produce the same results, respectively, as the calls to int() with non-default base values. They’re all just int to Python:

>>>

>>> 11

11

>>> 0b11 # Binary literal

3

>>> 0o11 # Octal literal

9

>>> 0x11 # Hex literal

17

Here’s how you could type the binary, octal, and hexadecimal equivalents of the decimal numbers 0 through 20. Any of these are perfectly valid in a Python interpreter shell or source code, and all work out to be of type int:

| Decimal | Binary | Octal | Hex |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

0b0 |

0o0 |

0x0 |

1 |

0b1 |

0o1 |

0x1 |

2 |

0b10 |

0o2 |

0x2 |

3 |

0b11 |

0o3 |

0x3 |

4 |

0b100 |

0o4 |

0x4 |

5 |

0b101 |

0o5 |

0x5 |

6 |

0b110 |

0o6 |

0x6 |

7 |

0b111 |

0o7 |

0x7 |

8 |

0b1000 |

0o10 |

0x8 |

9 |

0b1001 |

0o11 |

0x9 |

10 |

0b1010 |

0o12 |

0xa |

11 |

0b1011 |

0o13 |

0xb |

12 |

0b1100 |

0o14 |

0xc |

13 |

0b1101 |

0o15 |

0xd |

14 |

0b1110 |

0o16 |

0xe |

15 |

0b1111 |

0o17 |

0xf |

16 |

0b10000 |

0o20 |

0x10 |

17 |

0b10001 |

0o21 |

0x11 |

18 |

0b10010 |

0o22 |

0x12 |

19 |

0b10011 |

0o23 |

0x13 |

20 |

0b10100 |

0o24 |

0x14 |

It’s amazing just how prevalent these expressions are in the Python Standard Library. If you want to see for yourself, navigate to wherever your lib/python3.7/ directory sits, and check out the use of hex literals like this:

$ grep -nri --include "*.py" -e "b0x" lib/python3.7

This should work on any Unix system that has grep. You could use "b0o" to search for octal literals or “b0b” to search for binary literals.

What’s the argument for using these alternate int literal syntaxes? In short, it’s because 2, 8, and 16 are all powers of 2, while 10 is not. These three alternate number systems occasionally offer a way for expressing values in a computer-friendly manner. For example, the number 65536 or 216, is just 10000 in hexadecimal, or 0x10000 as a Python hexadecimal literal.

Enter Unicode

As you saw, the problem with ASCII is that it’s not nearly a big enough set of characters to accommodate the world’s set of languages, dialects, symbols, and glyphs. (It’s not even big enough for English alone.)

Unicode fundamentally serves the same purpose as ASCII, but it just encompasses a way, way, way bigger set of code points. There are a handful of encodings that emerged chronologically between ASCII and Unicode, but they are not really worth mentioning just yet because Unicode and one of its encoding schemes, UTF-8, has become so predominantly used.

Think of Unicode as a massive version of the ASCII table—one that has 1,114,112 possible code points. That’s 0 through 1,114,111, or 0 through 17 * (216) – 1, or 0x10ffff hexadecimal. In fact, ASCII is a perfect subset of Unicode. The first 128 characters in the Unicode table correspond precisely to the ASCII characters that you’d reasonably expect them to.

In the interest of being technically exacting, Unicode itself is not an encoding. Rather, Unicode is implemented by different character encodings, which you’ll see soon. Unicode is better thought of as a map (something like a dict) or a 2-column database table. It maps characters (like "a", "¢", or even "ቈ") to distinct, positive integers. A character encoding needs to offer a bit more.

Unicode contains virtually every character that you can imagine, including additional non-printable ones too. One of my favorites is the pesky right-to-left mark, which has code point 8207 and is used in text with both left-to-right and right-to-left language scripts, such as an article containing both English and Arabic paragraphs.

Unicode vs UTF-8

It didn’t take long for people to realize that all of the world’s characters could not be packed into one byte each. It’s evident from this that modern, more comprehensive encodings would need to use multiple bytes to encode some characters.

You also saw above that Unicode is not technically a full-blown character encoding. Why is that?

There is one thing that Unicode doesn’t tell you: it doesn’t tell you how to get actual bits from text—just code points. It doesn’t tell you enough about how to convert text to binary data and vice versa.

Unicode is an abstract encoding standard, not an encoding. That’s where UTF-8 and other encoding schemes come into play. The Unicode standard (a map of characters to code points) defines several different encodings from its single character set.

UTF-8 as well as its lesser-used cousins, UTF-16 and UTF-32, are encoding formats for representing Unicode characters as binary data of one or more bytes per character. We’ll discuss UTF-16 and UTF-32 in a moment, but UTF-8 has taken the largest share of the pie by far.

That brings us to a definition that is long overdue. What does it mean, formally, to encode and decode?

Encoding and Decoding in Python 3

Python 3’s str type is meant to represent human-readable text and can contain any Unicode character.

The bytes type, conversely, represents binary data, or sequences of raw bytes, that do not intrinsically have an encoding attached to it.

Encoding and decoding is the process of going from one to the other:

In .encode() and .decode(), the encoding parameter is "utf-8" by default, though it’s generally safer and more unambiguous to specify it:

>>>

>>> "résumé".encode("utf-8")

b'rxc3xa9sumxc3xa9'

>>> "El Niño".encode("utf-8")

b'El Nixc3xb1o'

>>> b"rxc3xa9sumxc3xa9".decode("utf-8")

'résumé'

>>> b"El Nixc3xb1o".decode("utf-8")

'El Niño'

The results of str.encode() is a bytes object. Both bytes literals (such as b"rxc3xa9sumxc3xa9") and the representations of bytes permit only ASCII characters.

This is why, when calling "El Niño".encode("utf-8"), the ASCII-compatible "El" is allowed to be represented as it is, but the n with tilde is escaped to "xc3xb1". That messy-looking sequence represents two bytes, 0xc3 and 0xb1 in hex:

>>>

>>> " ".join(f"{i:08b}" for i in (0xc3, 0xb1))

'11000011 10110001'

That is, the character ñ requires two bytes for its binary representation under UTF-8.

Python 3: All-In on Unicode

Python 3 is all-in on Unicode and UTF-8 specifically. Here’s what that means:

-

Python 3 source code is assumed to be UTF-8 by default. This means that you don’t need

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-at the top of.pyfiles in Python 3. -

All text (

str) is Unicode by default. Encoded Unicode text is represented as binary data (bytes). Thestrtype can contain any literal Unicode character, such as"Δv / Δt", all of which will be stored as Unicode. -

Python 3 accepts many Unicode code points in identifiers, meaning

résumé = "~/Documents/resume.pdf"is valid if this strikes your fancy. -

Python’s

remodule defaults to there.UNICODEflag rather thanre.ASCII. This means, for instance, thatr"w"matches Unicode word characters, not just ASCII letters. -

The default

encodinginstr.encode()andbytes.decode()is UTF-8.

There is one other property that is more nuanced, which is that the default encoding to the built-in open() is platform-dependent and depends on the value of locale.getpreferredencoding():

>>>

>>> # Mac OS X High Sierra

>>> import locale

>>> locale.getpreferredencoding()

'UTF-8'

>>> # Windows Server 2012; other Windows builds may use UTF-16

>>> import locale

>>> locale.getpreferredencoding()

'cp1252'

Again, the lesson here is to be careful about making assumptions when it comes to the universality of UTF-8, even if it is the predominant encoding. It never hurts to be explicit in your code.

One Byte, Two Bytes, Three Bytes, Four

A crucial feature is that UTF-8 is a variable-length encoding. It’s tempting to gloss over what this means, but it’s worth delving into.

Think back to the section on ASCII. Everything in extended-ASCII-land demands at most one byte of space. You can quickly prove this with the following generator expression:

>>>

>>> all(len(chr(i).encode("ascii")) == 1 for i in range(128))

True

UTF-8 is quite different. A given Unicode character can occupy anywhere from one to four bytes. Here’s an example of a single Unicode character taking up four bytes:

>>>

>>> ibrow = "🤨"

>>> len(ibrow)

1

>>> ibrow.encode("utf-8")

b'xf0x9fxa4xa8'

>>> len(ibrow.encode("utf-8"))

4

>>> # Calling list() on a bytes object gives you

>>> # the decimal value for each byte

>>> list(b'xf0x9fxa4xa8')

[240, 159, 164, 168]

This is a subtle but important feature of len():

- The length of a single Unicode character as a Python

strwill always be 1, no matter how many bytes it occupies. - The length of the same character encoded to

byteswill be anywhere between 1 and 4.

The table below summarizes what general types of characters fit into each byte-length bucket:

| Decimal Range | Hex Range | What’s Included | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 127 | "u0000" to "u007F" |

U.S. ASCII | "A", "n", "7", "&" |

| 128 to 2047 | "u0080" to "u07FF" |

Most Latinic alphabets* | "ę", "±", "ƌ", "ñ" |

| 2048 to 65535 | "u0800" to "uFFFF" |

Additional parts of the multilingual plane (BMP)** | "ത", "ᄇ", "ᮈ", "‰" |

| 65536 to 1114111 | "U00010000" to "U0010FFFF" |

Other*** | "𝕂", "𐀀", "😓", "🂲", |

*Such as English, Arabic, Greek, and Irish

**A huge array of languages and symbols—mostly Chinese, Japanese, and Korean by volume (also ASCII and Latin alphabets)

***Additional Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese characters, plus more symbols and emojis

What About UTF-16 and UTF-32?

Let’s get back to two other encoding variants, UTF-16 and UTF-32.

The difference between these and UTF-8 is substantial in practice. Here’s an example of how major the difference is with a round-trip conversion:

>>>

>>> letters = "αβγδ"

>>> rawdata = letters.encode("utf-8")

>>> rawdata.decode("utf-8")

'αβγδ'

>>> rawdata.decode("utf-16") # 😧

'뇎닎돎듎'

In this case, encoding four Greek letters with UTF-8 and then decoding back to text in UTF-16 would produce a text str that is in a completely different language (Korean).

Glaringly wrong results like this are possible when the same encoding isn’t used bidirectionally. Two variations of decoding the same bytes object may produce results that aren’t even in the same language.

This table summarizes the range or number of bytes under UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32:

| Encoding | Bytes Per Character (Inclusive) | Variable Length |

|---|---|---|

| UTF-8 | 1 to 4 | Yes |

| UTF-16 | 2 to 4 | Yes |

| UTF-32 | 4 | No |

One other curious aspect of the UTF family is that UTF-8 will not always take up less space than UTF-16. That may seem mathematically counterintuitive, but it’s quite possible:

>>>

>>> text = "記者 鄭啟源 羅智堅"

>>> len(text.encode("utf-8"))

26

>>> len(text.encode("utf-16"))

22

The reason for this is that the code points in the range U+0800 through U+FFFF (2048 through 65535 in decimal) take up three bytes in UTF-8 versus only two in UTF-16.

I’m not by any means recommending that you jump aboard the UTF-16 train, regardless of whether or not you operate in a language whose characters are commonly in this range. Among other reasons, one of the strong arguments for using UTF-8 is that, in the world of encoding, it’s a great idea to blend in with the crowd.

Not to mention, it’s 2019: computer memory is cheap, so saving 4 bytes by going out of your way to use UTF-16 is arguably not worth it.

Python’s Built-In Functions

You’ve made it through the hard part. Time to use what you’ve seen thus far in Python.

Python has a group of built-in functions that relate in some way to numbering systems and character encoding:

ascii()bin()bytes()chr()hex()int()oct()ord()str()

These can be logically grouped together based on their purpose:

-

ascii(),bin(),hex(), andoct()are for obtaining a different representation of an input. Each one produces astr. The first,ascii(), produces an ASCII only representation of an object, with non-ASCII characters escaped. The remaining three give binary, hexadecimal, and octal representations of an integer, respectively. These are only representations, not a fundamental change in the input. -