| Nash equilibrium | |

|---|---|

| A solution concept in game theory | |

| Relationship | |

| Subset of | Rationalizability, Epsilon-equilibrium, Correlated equilibrium |

| Superset of | Evolutionarily stable strategy, Subgame perfect equilibrium, Perfect Bayesian equilibrium, Trembling hand perfect equilibrium, Stable Nash equilibrium, Strong Nash equilibrium, Cournot equilibrium |

| Significance | |

| Proposed by | John Forbes Nash Jr. |

| Used for | All non-cooperative games |

In game theory, the Nash equilibrium, named after the mathematician John Nash, is the most common way to define the solution of a non-cooperative game involving two or more players. In a Nash equilibrium, each player is assumed to know the equilibrium strategies of the other players, and no one has anything to gain by changing only one’s own strategy.[1] The principle of Nash equilibrium dates back to the time of Cournot, who in 1838 applied it to competing firms choosing outputs.[2]

If each player has chosen a strategy – an action plan based on what has happened so far in the game – and no one can increase one’s own expected payoff by changing one’s strategy while the other players keep theirs unchanged, then the current set of strategy choices constitutes a Nash equilibrium.

If two players Alice and Bob choose strategies A and B, (A, B) is a Nash equilibrium if Alice has no other strategy available that does better than A at maximizing her payoff in response to Bob choosing B, and Bob has no other strategy available that does better than B at maximizing his payoff in response to Alice choosing A. In a game in which Carol and Dan are also players, (A, B, C, D) is a Nash equilibrium if A is Alice’s best response to (B, C, D), B is Bob’s best response to (A, C, D), and so forth.

Nash showed that there is a Nash equilibrium for every finite game (see Strategy (game theory)).

Applications[edit]

Game theorists use Nash equilibrium to analyze the outcome of the strategic interaction of several decision makers. In a strategic interaction, the outcome for each decision-maker depends on the decisions of the others as well as their own. The simple insight underlying Nash’s idea is that one cannot predict the choices of multiple decision makers if one analyzes those decisions in isolation. Instead, one must ask what each player would do taking into account what the player expects the others to do. Nash equilibrium requires that one’s choices be consistent: no players wish to undo their decision given what the others are deciding.

The concept has been used to analyze hostile situations such as wars and arms races[3] (see prisoner’s dilemma), and also how conflict may be mitigated by repeated interaction (see tit-for-tat). It has also been used to study to what extent people with different preferences can cooperate (see battle of the sexes), and whether they will take risks to achieve a cooperative outcome (see stag hunt). It has been used to study the adoption of technical standards,[citation needed] and also the occurrence of bank runs and currency crises (see coordination game). Other applications include traffic flow (see Wardrop’s principle), how to organize auctions (see auction theory), the outcome of efforts exerted by multiple parties in the education process,[4] regulatory legislation such as environmental regulations (see tragedy of the commons),[5] natural resource management,[6] analysing strategies in marketing,[7] even penalty kicks in football (see matching pennies),[8] energy systems, transportation systems, evacuation problems[9] and wireless communications.[10]

History[edit]

Nash equilibrium is named after American mathematician John Forbes Nash Jr. The same idea was used in a particular application in 1838 by Antoine Augustin Cournot in his theory of oligopoly.[11] In Cournot’s theory, each of several firms choose how much output to produce to maximize its profit. The best output for one firm depends on the outputs of the others. A Cournot equilibrium occurs when each firm’s output maximizes its profits given the output of the other firms, which is a pure-strategy Nash equilibrium. Cournot also introduced the concept of best response dynamics in his analysis of the stability of equilibrium. Cournot did not use the idea in any other applications, however, or define it generally.

The modern concept of Nash equilibrium is instead defined in terms of mixed strategies, where players choose a probability distribution over possible pure strategies (which might put 100% of the probability on one pure strategy; such pure strategies are a subset of mixed strategies). The concept of a mixed-strategy equilibrium was introduced by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in their 1944 book The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, but their analysis was restricted to the special case of zero-sum games. They showed that a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium will exist for any zero-sum game with a finite set of actions.[12] The contribution of Nash in his 1951 article “Non-Cooperative Games” was to define a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium for any game with a finite set of actions and prove that at least one (mixed-strategy) Nash equilibrium must exist in such a game. The key to Nash’s ability to prove existence far more generally than von Neumann lay in his definition of equilibrium. According to Nash, “an equilibrium point is an n-tuple such that each player’s mixed strategy maximizes his payoff if the strategies of the others are held fixed. Thus each player’s strategy is optimal against those of the others.” Putting the problem in this framework allowed Nash to employ the Kakutani fixed-point theorem in his 1950 paper to prove existence of equilibria. His 1951 paper used the simpler Brouwer fixed-point theorem for the same purpose.[13]

Game theorists have discovered that in some circumstances Nash equilibrium makes invalid predictions or fails to make a unique prediction. They have proposed many solution concepts (‘refinements’ of Nash equilibria) designed to rule out implausible Nash equilibria. One particularly important issue is that some Nash equilibria may be based on threats that are not ‘credible’. In 1965 Reinhard Selten proposed subgame perfect equilibrium as a refinement that eliminates equilibria which depend on non-credible threats. Other extensions of the Nash equilibrium concept have addressed what happens if a game is repeated, or what happens if a game is played in the absence of complete information. However, subsequent refinements and extensions of Nash equilibrium share the main insight on which Nash’s concept rests: the equilibrium is a set of strategies such that each player’s strategy is optimal given the choices of the others.

Definitions[edit]

Nash equilibrium[edit]

A strategy profile is a set of strategies, one for each player. Informally, a strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium if no player can do better by unilaterally changing their strategy. To see what this means, imagine that each player is told the strategies of the others. Suppose then that each player asks themselves: “Knowing the strategies of the other players, and treating the strategies of the other players as set in stone, can I benefit by changing my strategy?”

If any player could answer “Yes”, then that set of strategies is not a Nash equilibrium. But if every player prefers not to switch (or is indifferent between switching and not) then the strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium. Thus, each strategy in a Nash equilibrium is a best response to the other players’ strategies in that equilibrium.[14]

Formally, let

A game can have more than one Nash equilibrium. Even if the equilibrium is unique, it might be weak: a player might be indifferent among several strategies given the other players’ choices. It is unique and called a strict Nash equilibrium if the inequality is strict so one strategy is the unique best response:

Note that the strategy set

The Nash equilibrium may sometimes appear non-rational in a third-person perspective. This is because a Nash equilibrium is not necessarily Pareto optimal.

Nash equilibrium may also have non-rational consequences in sequential games because players may “threaten” each other with threats they would not actually carry out. For such games the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium may be more meaningful as a tool of analysis.

Strict/weak equilibrium[edit]

Suppose that in the Nash equilibrium, each player asks themselves: “Knowing the strategies of the other players, and treating the strategies of the other players as set in stone, would I suffer a loss by changing my strategy?”

If every player’s answer is “Yes”, then the equilibrium is classified as a strict Nash equilibrium.[15]

If instead, for some player, there is exact equality between the strategy in Nash equilibrium and some other strategy that gives exactly the same payout (i.e. this player is indifferent between switching and not), then the equilibrium is classified as a weak Nash equilibrium.

A game can have a pure-strategy or a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium. (In the latter a pure strategy is chosen stochastically with a fixed probability).

Nash’s existence theorem[edit]

Nash proved that if mixed strategies (where a player chooses probabilities of using various pure strategies) are allowed, then every game with a finite number of players in which each player can choose from finitely many pure strategies has at least one Nash equilibrium, which might be a pure strategy for each player or might be a probability distribution over strategies for each player.

Nash equilibria need not exist if the set of choices is infinite and non-compact. An example is a game where two players simultaneously name a number and the player naming the larger number wins. Another example is where each of two players chooses a real number strictly less than 5 and the winner is whoever has the biggest number; no biggest number strictly less than 5 exists (if the number could equal 5, the Nash equilibrium would have both players choosing 5 and tying the game). However, a Nash equilibrium exists if the set of choices is compact with each player’s payoff continuous in the strategies of all the players.[16]

Examples[edit]

Coordination game[edit]

| Player 1 strategy | Player 2 strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Player 2 adopts strategy A | Player 2 adopts strategy B | |

| Player 1 adopts strategy A |

4 4 |

3 1 |

| Player 1 adopts strategy B |

1 3 |

2 2 |

The coordination game is a classic two-player, two-strategy game, as shown in the example payoff matrix to the right. There are two pure-strategy equilibria, (A,A) with payoff 4 for each player and (B,B) with payoff 2 for each. The combination (B,B) is a Nash equilibrium because if either player unilaterally changes his strategy from B to A, his payoff will fall from 2 to 1.

| Player 1 strategy | Player 2 strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Hunt stag | Hunt rabbit | |

| Hunt stag |

2 2 |

1 0 |

| Hunt rabbit |

0 1 |

1 1 |

A famous example of a coordination game is the stag hunt. Two players may choose to hunt a stag or a rabbit, the stag providing more meat (4 utility units, 2 for each player) than the rabbit (1 utility unit). The caveat is that the stag must be cooperatively hunted, so if one player attempts to hunt the stag, while the other hunts the rabbit, the stag hunter will totally fail, for a payoff of 0, whereas the rabbit-hunter will succeed, for a payoff of 1. The game has two equilibria, (stag, stag) and (rabbit, rabbit), because a player’s optimal strategy depends on his expectation on what the other player will do. If one hunter trusts that the other will hunt the stag, he should hunt the stag; however if he thinks the other will hunt the rabbit, he too will hunt the rabbit. This game is used as an analogy for social cooperation, since much of the benefit that people gain in society depends upon people cooperating and implicitly trusting one another to act in a manner corresponding with cooperation.

Driving on a road against an oncoming car, and having to choose either to swerve on the left or to swerve on the right of the road, is also a coordination game. For example, with payoffs 10 meaning no crash and 0 meaning a crash, the coordination game can be defined with the following payoff matrix:

| Player 1 strategy | Player 2 strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Drive on the left | Drive on the right | |

| Drive on the left |

10 10 |

0 0 |

| Drive on the right |

0 0 |

10 10 |

In this case there are two pure-strategy Nash equilibria, when both choose to either drive on the left or on the right. If we admit mixed strategies (where a pure strategy is chosen at random, subject to some fixed probability), then there are three Nash equilibria for the same case: two we have seen from the pure-strategy form, where the probabilities are (0%, 100%) for player one, (0%, 100%) for player two; and (100%, 0%) for player one, (100%, 0%) for player two respectively. We add another where the probabilities for each player are (50%, 50%).

Network traffic[edit]

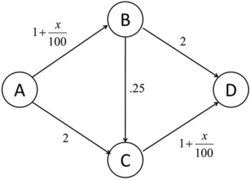

Sample network graph. Values on edges are the travel time experienced by a “car” traveling down that edge.

An application of Nash equilibria is in determining the expected flow of traffic in a network. Consider the graph on the right. If we assume that there are

This situation can be modeled as a “game”, where every traveler has a choice of 3 strategies and where each strategy is a route from A to D (one of ABD, ABCD, or ACD). The “payoff” of each strategy is the travel time of each route. In the graph on the right, a car travelling via ABD experiences travel time of

Notice that this distribution is not, actually, socially optimal. If the 100 cars agreed that 50 travel via ABD and the other 50 through ACD, then travel time for any single car would actually be 3.5, which is less than 3.75. This is also the Nash equilibrium if the path between B and C is removed, which means that adding another possible route can decrease the efficiency of the system, a phenomenon known as Braess’s paradox.

Competition game[edit]

| Player 1 strategy | Player 2 strategy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choose “0” | Choose “1” | Choose “2” | Choose “3” | |

| Choose “0” | 0, 0 | 2, −2 | 2, −2 | 2, −2 |

| Choose “1” | −2, 2 | 1, 1 | 3, −1 | 3, −1 |

| Choose “2” | −2, 2 | −1, 3 | 2, 2 | 4, 0 |

| Choose “3” | −2, 2 | −1, 3 | 0, 4 | 3, 3 |

This can be illustrated by a two-player game in which both players simultaneously choose an integer from 0 to 3 and they both win the smaller of the two numbers in points. In addition, if one player chooses a larger number than the other, then they have to give up two points to the other.

This game has a unique pure-strategy Nash equilibrium: both players choosing 0 (highlighted in light red). Any other strategy can be improved by a player switching their number to one less than that of the other player. In the adjacent table, if the game begins at the green square, it is in player 1’s interest to move to the purple square and it is in player 2’s interest to move to the blue square. Although it would not fit the definition of a competition game, if the game is modified so that the two players win the named amount if they both choose the same number, and otherwise win nothing, then there are 4 Nash equilibria: (0,0), (1,1), (2,2), and (3,3).

Nash equilibria in a payoff matrix[edit]

There is an easy numerical way to identify Nash equilibria on a payoff matrix. It is especially helpful in two-person games where players have more than two strategies. In this case formal analysis may become too long. This rule does not apply to the case where mixed (stochastic) strategies are of interest. The rule goes as follows: if the first payoff number, in the payoff pair of the cell, is the maximum of the column of the cell and if the second number is the maximum of the row of the cell – then the cell represents a Nash equilibrium.

| Player 1 strategy | Player 2 strategy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Option A | Option B | Option C | |

| Option A | 0, 0 | 25, 40 | 5, 10 |

| Option B | 40, 25 | 0, 0 | 5, 15 |

| Option C | 10, 5 | 15, 5 | 10, 10 |

We can apply this rule to a 3×3 matrix:

Using the rule, we can very quickly (much faster than with formal analysis) see that the Nash equilibria cells are (B,A), (A,B), and (C,C). Indeed, for cell (B,A), 40 is the maximum of the first column and 25 is the maximum of the second row. For (A,B), 25 is the maximum of the second column and 40 is the maximum of the first row; the same applies for cell (C,C). For other cells, either one or both of the duplet members are not the maximum of the corresponding rows and columns.

This said, the actual mechanics of finding equilibrium cells is obvious: find the maximum of a column and check if the second member of the pair is the maximum of the row. If these conditions are met, the cell represents a Nash equilibrium. Check all columns this way to find all NE cells. An N×N matrix may have between 0 and N×N pure-strategy Nash equilibria.

Stability[edit]

The concept of stability, useful in the analysis of many kinds of equilibria, can also be applied to Nash equilibria.

A Nash equilibrium for a mixed-strategy game is stable if a small change (specifically, an infinitesimal change) in probabilities for one player leads to a situation where two conditions hold:

- the player who did not change has no better strategy in the new circumstance

- the player who did change is now playing with a strictly worse strategy.

If these cases are both met, then a player with the small change in their mixed strategy will return immediately to the Nash equilibrium. The equilibrium is said to be stable. If condition one does not hold then the equilibrium is unstable. If only condition one holds then there are likely to be an infinite number of optimal strategies for the player who changed.

In the “driving game” example above there are both stable and unstable equilibria. The equilibria involving mixed strategies with 100% probabilities are stable. If either player changes their probabilities slightly, they will be both at a disadvantage, and their opponent will have no reason to change their strategy in turn. The (50%,50%) equilibrium is unstable. If either player changes their probabilities (which would neither benefit or damage the expectation of the player who did the change, if the other player’s mixed strategy is still (50%,50%)), then the other player immediately has a better strategy at either (0%, 100%) or (100%, 0%).

Stability is crucial in practical applications of Nash equilibria, since the mixed strategy of each player is not perfectly known, but has to be inferred from statistical distribution of their actions in the game. In this case unstable equilibria are very unlikely to arise in practice, since any minute change in the proportions of each strategy seen will lead to a change in strategy and the breakdown of the equilibrium.

The Nash equilibrium defines stability only in terms of unilateral deviations. In cooperative games such a concept is not convincing enough. Strong Nash equilibrium allows for deviations by every conceivable coalition.[17] Formally, a strong Nash equilibrium is a Nash equilibrium in which no coalition, taking the actions of its complements as given, can cooperatively deviate in a way that benefits all of its members.[18] However, the strong Nash concept is sometimes perceived as too “strong” in that the environment allows for unlimited private communication. In fact, strong Nash equilibrium has to be Pareto efficient. As a result of these requirements, strong Nash is too rare to be useful in many branches of game theory. However, in games such as elections with many more players than possible outcomes, it can be more common than a stable equilibrium.

A refined Nash equilibrium known as coalition-proof Nash equilibrium (CPNE)[17] occurs when players cannot do better even if they are allowed to communicate and make “self-enforcing” agreement to deviate. Every correlated strategy supported by iterated strict dominance and on the Pareto frontier is a CPNE.[19] Further, it is possible for a game to have a Nash equilibrium that is resilient against coalitions less than a specified size, k. CPNE is related to the theory of the core.

Finally in the eighties, building with great depth on such ideas Mertens-stable equilibria were introduced as a solution concept. Mertens stable equilibria satisfy both forward induction and backward induction. In a game theory context stable equilibria now usually refer to Mertens stable equilibria.

Occurrence[edit]

If a game has a unique Nash equilibrium and is played among players under certain conditions, then the NE strategy set will be adopted. Sufficient conditions to guarantee that the Nash equilibrium is played are:

- The players all will do their utmost to maximize their expected payoff as described by the game.

- The players are flawless in execution.

- The players have sufficient intelligence to deduce the solution.

- The players know the planned equilibrium strategy of all of the other players.

- The players believe that a deviation in their own strategy will not cause deviations by any other players.

- There is common knowledge that all players meet these conditions, including this one. So, not only must each player know the other players meet the conditions, but also they must know that they all know that they meet them, and know that they know that they know that they meet them, and so on.

Where the conditions are not met[edit]

Examples of game theory problems in which these conditions are not met:

- The first condition is not met if the game does not correctly describe the quantities a player wishes to maximize. In this case there is no particular reason for that player to adopt an equilibrium strategy. For instance, the prisoner’s dilemma is not a dilemma if either player is happy to be jailed indefinitely.

- Intentional or accidental imperfection in execution. For example, a computer capable of flawless logical play facing a second flawless computer will result in equilibrium. Introduction of imperfection will lead to its disruption either through loss to the player who makes the mistake, or through negation of the common knowledge criterion leading to possible victory for the player. (An example would be a player suddenly putting the car into reverse in the game of chicken, ensuring a no-loss no-win scenario).

- In many cases, the third condition is not met because, even though the equilibrium must exist, it is unknown due to the complexity of the game, for instance in Chinese chess.[20] Or, if known, it may not be known to all players, as when playing tic-tac-toe with a small child who desperately wants to win (meeting the other criteria).

- The criterion of common knowledge may not be met even if all players do, in fact, meet all the other criteria. Players wrongly distrusting each other’s rationality may adopt counter-strategies to expected irrational play on their opponents’ behalf. This is a major consideration in “chicken” or an arms race, for example.

Where the conditions are met[edit]

In his Ph.D. dissertation, John Nash proposed two interpretations of his equilibrium concept, with the objective of showing how equilibrium points can be connected with observable phenomenon.

(…) One interpretation is rationalistic: if we assume that players are rational, know the full structure of the game, the game is played just once, and there is just one Nash equilibrium, then players will play according to that equilibrium.

This idea was formalized by R. Aumann and A. Brandenburger, 1995, Epistemic Conditions for Nash Equilibrium, Econometrica, 63, 1161-1180 who interpreted each player’s mixed strategy as a conjecture about the behaviour of other players and have shown that if the game and the rationality of players is mutually known and these conjectures are commonly known, then the conjectures must be a Nash equilibrium (a common prior assumption is needed for this result in general, but not in the case of two players. In this case, the conjectures need only be mutually known).

A second interpretation, that Nash referred to by the mass action interpretation, is less demanding on players:

[i]t is unnecessary to assume that the participants have full knowledge of the total structure of the game, or the ability and inclination to go through any complex reasoning processes. What is assumed is that there is a population of participants for each position in the game, which will be played throughout time by participants drawn at random from the different populations. If there is a stable average frequency with which each pure strategy is employed by the average member of the appropriate population, then this stable average frequency constitutes a mixed strategy Nash equilibrium.

For a formal result along these lines, see Kuhn, H. and et al., 1996, “The Work of John Nash in Game Theory,” Journal of Economic Theory, 69, 153–185.

Due to the limited conditions in which NE can actually be observed, they are rarely treated as a guide to day-to-day behaviour, or observed in practice in human negotiations. However, as a theoretical concept in economics and evolutionary biology, the NE has explanatory power. The payoff in economics is utility (or sometimes money), and in evolutionary biology is gene transmission; both are the fundamental bottom line of survival. Researchers who apply games theory in these fields claim that strategies failing to maximize these for whatever reason will be competed out of the market or environment, which are ascribed the ability to test all strategies. This conclusion is drawn from the “stability” theory above. In these situations the assumption that the strategy observed is actually a NE has often been borne out by research.[21]

NE and non-credible threats[edit]

Extensive and Normal form illustrations that show the difference between SPNE and other NE. The blue equilibrium is not subgame perfect because player two makes a non-credible threat at 2(2) to be unkind (U).

The Nash equilibrium is a superset of the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium. The subgame perfect equilibrium in addition to the Nash equilibrium requires that the strategy also is a Nash equilibrium in every subgame of that game. This eliminates all non-credible threats, that is, strategies that contain non-rational moves in order to make the counter-player change their strategy.

The image to the right shows a simple sequential game that illustrates the issue with subgame imperfect Nash equilibria. In this game player one chooses left(L) or right(R), which is followed by player two being called upon to be kind (K) or unkind (U) to player one, However, player two only stands to gain from being unkind if player one goes left. If player one goes right the rational player two would de facto be kind to her/him in that subgame. However, The non-credible threat of being unkind at 2(2) is still part of the blue (L, (U,U)) Nash equilibrium. Therefore, if rational behavior can be expected by both parties the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium may be a more meaningful solution concept when such dynamic inconsistencies arise.

Proof of existence[edit]

Proof using the Kakutani fixed-point theorem[edit]

Nash’s original proof (in his thesis) used Brouwer’s fixed-point theorem (e.g., see below for a variant). We give a simpler proof via the Kakutani fixed-point theorem, following Nash’s 1950 paper (he credits David Gale with the observation that such a simplification is possible).

To prove the existence of a Nash equilibrium, let

Here,

Kakutani’s fixed point theorem guarantees the existence of a fixed point if the following four conditions are satisfied.

is compact, convex, and nonempty.

is nonempty.

is upper hemicontinuous

is convex.

Condition 1. is satisfied from the fact that

Condition 2. and 3. are satisfied by way of Berge’s maximum theorem. Because

Condition 4. is satisfied as a result of mixed strategies. Suppose

Therefore, there exists a fixed point in

When Nash made this point to John von Neumann in 1949, von Neumann famously dismissed it with the words, “That’s trivial, you know. That’s just a fixed-point theorem.” (See Nasar, 1998, p. 94.)

Alternate proof using the Brouwer fixed-point theorem[edit]

We have a game

We can now define the gain functions. For a mixed strategy

The gain function represents the benefit a player gets by unilaterally changing their strategy. We now define

for

Next we define:

It is easy to see that each

This simply states that each player gains no benefit by unilaterally changing their strategy, which is exactly the necessary condition for a Nash equilibrium.

Now assume that the gains are not all zero. Therefore,

So let

Also we shall denote

Since

To see this, we first note that if

and so the left term is zero, giving us that the entire expression is

So we finally have that

where the last inequality follows since

Computing Nash equilibria[edit]

If a player A has a dominant strategy

In games with mixed-strategy Nash equilibria, the probability of a player choosing any particular (so pure) strategy can be computed by assigning a variable to each strategy that represents a fixed probability for choosing that strategy. In order for a player to be willing to randomize, their expected payoff for each (pure) strategy should be the same. In addition, the sum of the probabilities for each strategy of a particular player should be 1. This creates a system of equations from which the probabilities of choosing each strategy can be derived.[14]

Examples[edit]

| Strategy | Player B plays H | Player B plays T |

|---|---|---|

| Player A plays H | −1, +1 | +1, −1 |

| Player A plays T | +1, −1 | −1, +1 |

In the matching pennies game, player A loses a point to B if A and B play the same strategy and wins a point from B if they play different strategies. To compute the mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium, assign A the probability

Thus, a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium in this game is for each player to randomly choose H or T with

Oddness of equilibrium points[edit]

In 1971, Robert Wilson came up with the Oddness Theorem, [23] which says that “almost all” finite games have a finite and odd number of Nash equilibria. In 1993, Harsanyi published an alternative proof of the result.[24] “Almost all” here means that any game with an infinite or even number of equilibria is very special in the sense that if its payoffs were even slightly randomly perturbed, with probability one it would have an odd number of equilibria instead.

| Strategy | Player B votes Yes | Player B votes No |

|---|---|---|

| Player A votes Yes | 1, 1 | 0, 0 |

| Player A votes No | 0, 0 | 0, 0 |

The prisoner’s dilemma, for example, has one equilibrium, while the battle of the sexes has three– two pure and one mixed, and this remains true even if the payoffs change slightly. The free money game is an example of a “special” game with an even number of equilibria. In it, two players have to both vote “yes” rather than “no” to get a reward and the votes are simultaneous. There are two pure-strategy Nash equilibria, (yes, yes) and (no, no), and no mixed strategy equilibria, because the strategy “yes” weakly dominates “no”. “Yes” is as good as “no” regardless of the other player’s action, but if there is any chance the other player chooses “yes” then “yes” is the best reply. Under a small random perturbation of the payoffs, however, the probability that any two payoffs would remain tied, whether at 0 or some other number, is vanishingly small, and the game would have either one or three equilibria instead.

See also[edit]

- Adjusted winner procedure – Method of fairly dividing property

- Complementarity theory – type of mathematical optimization problem

- Conflict resolution research

- Cooperation – Groups working or acting together

- Equilibrium selection

- Evolutionarily stable strategy – Solution concept in game theory

- Glossary of game theory – List of definitions of terms and concepts used in game theory

- Hotelling’s law – Observation in economics

- Manipulated Nash equilibrium

- Mexican standoff – Type of confrontation

- Minimax theorem – Gives conditions that guarantee the max–min inequality is also an equality

- Mutual assured destruction – Doctrine of military strategy

- Extended Mathematical Programming for Equilibrium Problems

- Optimum contract and par contract – Bridge scoring terms in the card game contract bridge

- Self-confirming equilibrium

- Solution concept – Formal rule for predicting how a game will be played

- Stackelberg competition – Economic model

- Wardrop’s principle – Major theorist of traffic flow equilibrium

References[edit]

- ^ Osborne, Martin J.; Rubinstein, Ariel (12 Jul 1994). A Course in Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT. p. 14. ISBN 9780262150415.

- ^ Kreps D.M. (1987) “Nash Equilibrium.” In: Palgrave Macmillan (eds) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- ^ Schelling, Thomas, The Strategy of Conflict, copyright 1960, 1980, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-84031-3.

- ^ De Fraja, G.; Oliveira, T.; Zanchi, L. (2010). “Must Try Harder: Evaluating the Role of Effort in Educational Attainment”. Review of Economics and Statistics. 92 (3): 577. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00013. hdl:2108/55644. S2CID 57072280.

- ^ Ward, H. (1996). “Game Theory and the Politics of Global Warming: The State of Play and Beyond”. Political Studies. 44 (5): 850–871. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00338.x. S2CID 143728467.,

- ^ Thorpe, Robert B.; Jennings, Simon; Dolder, Paul J. (2017). “Risks and benefits of catching pretty good yield in multispecies mixed fisheries”. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 74 (8): 2097–2106. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsx062.,

- ^ “Marketing Lessons from Dr. Nash – Andrew Frank”. 2015-05-25. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- ^ Chiappori, P. -A.; Levitt, S.; Groseclose, T. (2002). “Testing Mixed-Strategy Equilibria when Players Are Heterogeneous: The Case of Penalty Kicks in Soccer” (PDF). American Economic Review. 92 (4): 1138. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.178.1646. doi:10.1257/00028280260344678.

- ^ Djehiche, B.; Tcheukam, A.; Tembine, H. (2017). “A Mean-Field Game of Evacuation in Multilevel Building”. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 62 (10): 5154–5169. doi:10.1109/TAC.2017.2679487. ISSN 0018-9286. S2CID 21850096.

- ^ Djehiche, Boualem; Tcheukam, Alain; Tembine, Hamidou (2017-09-27). “Mean-Field-Type Games in Engineering”. AIMS Electronics and Electrical Engineering. 1: 18–73. arXiv:1605.03281. doi:10.3934/ElectrEng.2017.1.18. S2CID 16055840.

- ^ Cournot A. (1838) Researches on the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth

- ^ J. Von Neumann, O. Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, copyright 1944, 1953, Princeton University Press

- ^ Carmona, Guilherme; Podczeck, Konrad (2009). “On the Existence of Pure Strategy Nash Equilibria in Large Games” (PDF). Journal of Economic Theory. 144 (3): 1300–1319. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2008.11.009. hdl:10362/11577. SSRN 882466.

- ^ a b von Ahn, Luis. “Preliminaries of Game Theory” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ^ “Nash Equilibria”. hoylab.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ MIT OpenCourseWare. 6.254: Game Theory with Engineering Applications, Spring 2010. Lecture 6: Continuous and Discontinuous Games.

- ^ a b B. D. Bernheim; B. Peleg; M. D. Whinston (1987), “Coalition-Proof Equilibria I. Concepts”, Journal of Economic Theory, 42 (1): 1–12, doi:10.1016/0022-0531(87)90099-8.

- ^ Aumann, R. (1959). “Acceptable points in general cooperative n-person games”. Contributions to the Theory of Games. Vol. IV. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8216-8.

- ^ D. Moreno; J. Wooders (1996), “Coalition-Proof Equilibrium” (PDF), Games and Economic Behavior, 17 (1): 80–112, doi:10.1006/game.1996.0095, hdl:10016/4408.

- ^ T. L. Turocy, B. Von Stengel, Game Theory, copyright 2001, Texas A&M University, London School of Economics, pages 141-144. Nash proved that a perfect NE exists for this type of finite extensive form game[citation needed] – it can be represented as a strategy complying with his original conditions for a game with a NE. Such games may not have unique NE, but at least one of the many equilibrium strategies would be played by hypothetical players having perfect knowledge of all 10150 game trees[citation needed].

- ^ J. C. Cox, M. Walker, Learning to Play Cournot Duoploy Strategies Archived 2013-12-11 at the Wayback Machine, copyright 1997, Texas A&M University, University of Arizona, pages 141-144

- ^ Fudenburg, Drew; Tirole, Jean (1991). Game Theory. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-06141-4.

- ^ Wilson, Robert (1971-07-01). “Computing Equilibria of N-Person Games”. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics. 21 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1137/0121011. ISSN 0036-1399.

- ^ Harsanyi, J. C. (1973-12-01). “Oddness of the Number of Equilibrium Points: A New Proof”. International Journal of Game Theory. 2 (1): 235–250. doi:10.1007/BF01737572. ISSN 1432-1270. S2CID 122603890.

Bibliography[edit]

Game theory textbooks[edit]

- Binmore, Ken (2007), Playing for Real: A Text on Game Theory, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195300574.

- Dixit, Avinash, Susan Skeath and David Reiley. Games of Strategy. W.W. Norton & Company. (Third edition in 2009.) An undergraduate text.

- Dutta, Prajit K. (1999), Strategies and games: theory and practice, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-04169-0. Suitable for undergraduate and business students.

- Fudenberg, Drew and Jean Tirole (1991) Game Theory MIT Press.

- Gibbons, Robert (1992), Game Theory for Applied Economists, Princeton University Press (July 13, 1992), ISBN 978-0-691-00395-5. Lucid and detailed introduction to game theory in an explicitly economic context.

- Morgenstern, Oskar and John von Neumann (1947) The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior Princeton University Press.

- Myerson, Roger B. (1997), Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-34116-6

- Osborne, Martin (2004), An Introduction to Game Theory, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-512895-6.

- Papayoanou, Paul (2010), Game Theory for Business: A Primer in Strategic Gaming, Probabilistic Publishing, ISBN 978-0964793873

- Rubinstein, Ariel; Osborne, Martin J. (1994), A Course in Game Theory, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-65040-3. A modern introduction at the graduate level.

- Shoham, Yoav; Leyton-Brown, Kevin (2009), Multiagent Systems: Algorithmic, Game-Theoretic, and Logical Foundations, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89943-7. A comprehensive reference from a computational perspective; see Chapter 3. Downloadable free online.

Original Nash papers[edit]

- Nash, John (1950) “Equilibrium points in n-person games” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 36(1):48-49.

- Nash, John (1951) “Non-Cooperative Games” The Annals of Mathematics 54(2):286-295.

Other references[edit]

- Mehlmann, A. (2000) The Game’s Afoot! Game Theory in Myth and Paradox, American Mathematical Society.

- Nasar, Sylvia (1998), A Beautiful Mind, Simon & Schuster.

- Aviad Rubinstein: “Hardness of Approximation Between P and NP”, ACM, ISBN 978-1-947487-23-9 (May 2019), DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3241304 . # Explains the Nash Equilibrium is a hard problem in computation.

External links[edit]

- “Nash theorem (in game theory)”, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Complete Proof of Existence of Nash Equilibria

- Simplified Form and Related Results Archived 2021-07-31 at the Wayback Machine

Частным случаем

неантагонистической игры является

игра, в которой принимают участие два

игрока, каждый из которых имеет конечное

число стратегий. Такие игры можно описать

с помощью двух матриц, поэтому они

называются биматричными.

Пусть первый

участник имеет

стратегий, а второй –

стратегий. Количество исходов равно

.

Функция выигрышей первого участника

может быть задана платёжной матрицейсостоящую из элементов

.

Аналогично функция выигрышей второго

участника будет задаваться матрицейсостоящую из элементов

Игру можно также описать с помощью

таблицы.

В каждой клетке такой таблицы указывается

два числа, где первое число – это выигрыш

первого участника, а второе число –

выигрыш второго.

Рассмотрим пример.

Пример.

Игра «Двое

в горящем доме».

Два человека находятся в горящем доме

по разные стороны двери, которую нужно

открыть для спасения каждого из них.

Для того чтобы дверь открылась, им обоим

необходимо приложить общие усилия,

заключающиеся в том, что один должен

потянуть за ручку двери, а второй, в свою

очередь, должен её толкнуть. Запишем

эту игры в матричной форме:

|

первый игрок |

|||

|

Толкать |

Не |

||

|

второй игрок |

Тянуть |

100; |

0; |

|

Не |

0; |

0; |

Выпишем платёжную

матрицу для первого игрока, в которой

первая строка доминирует вторую:

В платёжной матрице

второго игрока первый столбец доминирует

второй:

В этой игре каждому

из участников нет необходимости сообщать

партнёру о своих намерениях. Если игроки

абсолютно рациональны, то каждый из них

выберет свою доминирующую стратегию,

обеспечивающую наилучший исход для

обоих игроков.

§2.2.3. Равновесие Нэша

Рассмотрим

неантагонистическую игру двух лиц. с

функциями выигрышей

и

Исход игры будем называтьравновесным,

если ни одному из участников не выгодно

отклоняться от нёё в одностороннем

порядке. Именной такой смысл понятию

равновесие придал Джон Нэш. Запишем

строгое определение равновесия

по Нэшу.

Стратегии

и

называютсястратегиями

равновесными по Нэшу,

если выполняются следующие неравенства:

(2.3)

Таким образом,

равновесие Нэша характеризуется тем,

что ни одному из участников не выгодно

отклоняться от своей равновесной

стратегии, если другой участник применяет

стратегию, равновесную по Нэшу. Заметим,

что это определение сохраняется и для

игры с любым числом участников.

Пример.

Найти равновесные по Нэшу стратегии в

примере 2 (Таблица 1).

Решение.

Выпишем все возможные стратегии обоих

участников в матрицу и отыщем для каждого

из исходов альтернативные исходы, более

предпочтительные с точки зрения одного

из игроков:

В игре имеется

два равновесия по Нэшу.

Как правило, равновесие по Нэшу не

является единственным.

Существуют игры,

в которых нет равновесия в чистых

стратегиях. Кроме равновесия в чистых

стратегиях случае, может существовать

равновесие Нэша в смешанных стратегиях.

Смысл смешанной

стратегии для биматричной игры будем

определять так же, как и для матричных

игр. Смешанная стратегия первого и

второго участников есть соответственно

вектора X={x1,

x2,…xm}

и Y={y1,

y2,…,

yn},

где

и

(2.4)

Множества смешанных

стратегий будем обозначать так же, как

множества чистых стратегий – Sx

для 1-го игрока и Sy

для 2-го.

Функции выигрышей

первого и второго игроков при смешанных

стратегиях X

и Y определяются по формулам

Η1(x,y)=∑aijxiyj,

Η2(x,y)=∑bijxiyj

(2.5)

Равновесные по

Нэшу смешанные стратегии будем обозначать

X*

и Y*

соответственно. Вопрос существования

равновесия по Нэшу решается следующей

теоремой, доказанной Дж. Нэшем.

Теорема о

равновесии по Нэшу.

В любой биматричной игре существует,

по крайней мере, одно равновесие Нэша.

(Без доказательства).

Замечание.

Это могут быть равновесия в чистых или

смешанных стратегиях.

В общем случае

биматричной игры нахождение смешанных

равновесий является сложной задачей,

но для матриц размера 2×2

решение в смешанных стратегиях найти

несложно.

Рассмотрим

биматричную игру, в которой каждый игрок

имеет две чистые стратегии. Смешанные

стратегии игроков будем обозначать

x={x1,

x2}

и y={y1,

y2}

соответственно, где 0≤xi≤1,

0≤yj≤1,

x1+x2=1,

y1+y2=1.

Обозначая элементы платежных матриц

1-го и 2-го игроков aij

и bij

соответственно, получим Таблицу3 и

Таблицу 4 для расчета функций выигрыша.

Таблица3

Таблица 4

|

y1 |

y2 |

|

|

x1 |

a11 |

a |

|

x2 |

a |

a |

|

y1 |

y2 |

|

|

x1 |

b11 |

b |

|

x2 |

b |

b |

Функция выигрыша

1-го игрока будет равна

Η1(x,y)=

x1(a11

y1+

a

12

y2)+

x2(a

21

y1+

a

22

y2),

подставляя x2=1-

x1

и y2=1-

y1,

получим

Η1(x,y)=

x1(y1(a11+

a

22–

a

12-a

21)+

a

12-a

22)+

y1(a

21–

a

22)+

a

22.

Обозначим x*={x1*,

x2*}

и y

*={

y

1*,

y

2*}

равновесные по Нэшу стратегии игроков

и найдем функцию выигрыша 1-го игрока,

при условии, что 2-й игрок применит

равновесную по Нэшу стратегию y*,

а 1-й игрок применит произвольную

смешанную стратегию x

Η1(x,y*)=

x1(y1*(a11+

a

22–

a

12-a

21)+

a

12-a

22)+

y1*(a

21–

a

22)+

a

22.

(2.6)

Если 2-й игрок

применит равновесную по Нэшу стратегию

y*,

и 1-й игрок применит равновесную по Нэшу

стратегию x*,

то функция выигрыша 1-го игрока будет

равна

Η1(x*,y*)=

x1*(y1*(a11+

a

22–

a

12-a

21)+

a

12-a

22)+

y1*(a

21–

a

22)+

a

22.

(2.7)

Согласно определению

равновесия по Нэшу для всех смешанных

стратегий x

должно выполняться неравенство

Η1(x*,y*)≥

Η1(x,y*).

(2.8)

Подставляя в

неравенство Η1(x*,y*)-

Η1(x,y*)≥0

функции из уравнений (4) и (5), получим

неравенство

(x1*–

x1)(

y1*(a11+

a

22– a

12-a

21)+ a

12-a

22)

≥0, (2.9)

которое должно

выполняться для всех значений x1

из отрезка [0;1].

Интерес представляет

случай, когда равновесная по Нэшу

стратегия x*

не совпадает ни с одной чистой стратегией,

то есть, когда x1*

удовлетворяет строгому неравенству 0<

x1*<1.

В этом случае неравенство (2.9) будет

верно для всех x1

из отрезка [0;1] тогда и только тогда,

когда

y1*(a11+

a

22– a

12-a

21)+ a

12-a

22=0.

(2.10)

Уравнение (2.10) дает

значение y1*,

при котором существует смешанная

стратегия x*,

не совпадающая с чистыми стратегиями

1-го игрока.

Аналогично, для

всех смешанных стратегий y

2-го игрока должно выполняться неравенство

Η2(x*,y*)≥

Η2(x*,y)

(2.11)

Определяя функции

Η2(x*,y)

и Η2(x*,y*)

из таблицы 2, получим условие, при котором

2-й игрок имеет равновесную смешанную

стратегию y*.

не совпадающую с его чистыми стратегиями

x

1*(

b 11+

b 22–

b 12–

b 21)+

b 21–

b 22=0.

(2.12)

Если уравнения

(2.10) или (2.12) не имеют решений на отрезке

[0;1], то в игре существуют только равновесия

в чистых стратегиях, существование

которых непосредственно следует из

неравенств (2.9) и аналогичного неравенства

для 2-го игрока.

Пример.Отыскать равновесие

Нэша в чистых, либо смешанных стратегиях

в игре «орёл-решка».

Таблица 5

|

первый игрок |

|||

|

орёл |

решка |

||

|

второй игрок |

орёл |

1; |

-1; |

|

решка |

-1; |

1; |

Решение.

Запишем

матрицу игры:

Таблица

6

Очевидно, что

равновесия по Нэшу в чистых стратегиях

не существует. Будем искать решение в

смешанных стратегияхx={x1,

x2}

и y={y1,

y2}

соответственно, где 0≤xi≤1,

0≤yj≤1,

x1+x2=1,

y1+y2=1.

Найдем функцию выигрыша 1-го игрока

Η1(x,y)=

x1y1–

x1y2–

x2y1+

x2y2=

4x1y1-2

x1-2y1+1=

x1(4y1-2)

-2y1+1.

Для равновесных

по Нэшу стратегий x*={x1*,

x2*}

и y*={

y

1*,

y

2*}

найдем значение функции выигрыша будет

равно

Η1(x*,y*)=

x1*(4y1*-2)

-2y1*+1

Если 2-й игрок

применит равновесную по Нэшу стратегию

y*,

а 1-й игрок произвольную смешанную

стратегию x, то функция выигрыша 1-го

игрока составит значение

Η1(x,y*)=

x1

(4y1*-2)

-2y1*+1.

Из условия равновесия

Η1(x*,y*)≥

Η1(x,y*)

следует неравенство

(x1*–

x1)

(4y1*-2)

≥0

для всех x1

из отрезка [0;1]. Поскольку в игре нет

равновесия в чистых стратегиях, то x1*≠0

и x1*≠1,

то множитель (x1*–

x1)

может быть и положительным и отрицательным

в зависимости от x1.

Следовательно, последнее неравенство

выполняется лишь при условии, что второй

множитель равен нулю, то есть 4y1*-2=0.

Откуда находим y

1*=0,5

и y

2*=0,5.

Аналогично находим

равновесную по Нэшу стратегию 1-го игрока

x1*=

x2*=0,5.

Значения игры для 1-го и 2-го игроков

равны Η1(x*,y*)=

Η2(x*,y*)=0,5.

Пример.

«Семейный

спор». Муж

и жена собираются провести вместе

выходной день. Муж предпочитает пойти

на футбол, а жена на балет. Выигрыши мужа

и жены в зависимости от принятых стратегий

приведены в таблице:

Таблица 7

|

жена |

|||

|

Футбол |

балет |

||

|

муж |

футбол |

2; |

0,5; |

|

балет |

0; |

1; |

Решение.

Выпишем общую матрицу игры.

В этой игре

существует два равновесия Нэша в чистых

стратегиях. Кроме того, можно показать,

что существует равновесие Нэша и в

смешанных стратегиях. Для этого найдем

платежную функцию 1-го игрока (мужа) для

смешанных стратегий x={x1,

x2}

и y={y1,

y2}.

Η1(x,y)=2x1y1+0,5

x1y2+x2y2=1,5

x1y1-0,5

x1+

y1-1=

x1(2,5

y1-0,5)

+1- y1.

Соответственно

получаем

Η1(x*,y*)-

Η1(x,y*)=(x1*–

x1)

(2,5y1*-0,5).

Неравенство

Η1(x*,y*)≥

Η1(x,y*)

будет верно для всех x1

из отрезка [0;1] и 0< x1*<1,

если 2,5y1*-0,5=0,

откуда y

1*=1/5

и y

2*=4/5.

Аналогично, для

2-го игрока (жены) получаем платежную

функцию

Η2(x,y)=

x1y1+0,5

x1y2+2x2y2=2,5x1y1-2y1-1,5x1+2.

Тогда Η2(x*,y*)-

Η2(x*,y)=(

y1*–

y1)

(2,5 x

1*-2).

Неравенство

Η2(x*,y*)≥Η2(x*,y)

будет верно для равновесной смешанной

стратегии y*={y1*,y2*}

и произвольной стратегии y={y1,

y2}

при условии, что 2,5x1*-2=0,

откуда находим x1*=4/5,

x2*=1/5

(муж выбирает футбол с вероятностью 4/5

и балет с вероятностью 1/5).

Аналогично находим

y 1*=1/5,

y 2*=4/5.

Функции выигрыш игроков в смешанном

равновесии будут равны Η1(x*,y*)=

Η2(x*,y*)=4/5.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Содержание

- Равновесие Нэша против доминирующей стратегии

- Нахождение равновесия Нэша

- Пример

Равновесие Нэша являет собой исход экономической игры, в которой изменение стратегии одним игроком никак не влияет на вероятность его выигрыша.

Достичь такого равновесия можно за счет реализации каждым из игроков оптимальной стратегии и принятия во внимание стратегии соперника.

Термин «равновесие Нэша» назван в честь одного из выдающихся разработчиков теории игр Джона Нэша, которого в фильме «Прекрасный ум» сыграл Рассел Кроу.

Наиболее важным свойством равновесия Нэша является то, что оно самоподдерживается. Это тот результат, которого два рациональных игрока А и B должны в конечном счете достичь в некооперативной игре.

Оно сохраняет стабильность из-за неспособности ни одного из игроков за счет изменения стратегии повлиять на конечный результат.

Игрок А достигает равновесия Нэша, используя стратегию, которая является его лучшим ответом на стратегию, выбранную его противником, игроком В.

Но поскольку противник B также выбирает стратегию, дающую ему максимальный выигрыш с учетом принимаемых игроком A решений, игра тяготеет к неизбежному результату. Этот результат и называется равновесием Нэша.

Хотя каждый игрок заинтересован в достижении равновесия Нэша, последнее не обязательно должно максимизировать совокупный выигрыш. Классическим примером этого явления служит уже вскользь рассмотренная нами дилемма заключенных.

Равновесие Нэша против доминирующей стратегии

Доминирующую стратегию можно рассматривать в качестве частного случая равновесия Нэша.

Доминирующая стратегия приводит к наилучшему выигрышу для игрока независимо от того, что делает другая фирма. Равновесие же Нэша представляет собой стратегию, которая максимизирует выигрыш, учитывая то, что другой игрок будет делать.

Равновесие Нэша «заточено» на стремление обоих соперников показать себя в лучшем свете в процессе достижения собственных целей. Мы достигаем его, предполагая, что наш конкурент рационален. Правда, мы можем следовать доминирующей стратегии, не прогнозируя ожидаемую стратегию противник A.

Игра имеет равновесие Нэша, даже если нет доминирующей стратегии (см. пример ниже). Кроме того, игра может иметь несколько равновесий Нэша.

Нахождение равновесия Нэша

Следующие правила полезны для определения равновесия Нэша в игре:

- Следование обоими игроками доминирующим стратегиям, которые обеспечивают им лучший выигрыш независимо от действий и решений соперника, ячейка, в которой пересекаются доминирующие стратегии обоих игроков, является равновесием Нэша.

- Если у одного игрока есть доминирующая стратегия, то ячейка в строке или столбце доминирующей стратегии, в которой противник имеет максимальный выигрыш, является равновесием Нэша.

- Если ни одна фирма не имеет доминирующей стратегии, следует определить любые доминирующие стратегии и вычеркнуть эти ячейки. Определить максимальные выплаты для каждого игрока в каждой строке и столбце и поставить галочки напротив них. Ячейки, в которых проверяются оба выигрыша, показывают потенциальное равновесие Нэша.

Пример

Давайте рассмотрим две фирмы A и B, которые должны решить, каков их рекламный бюджет. Следующая матрица выплат показывает чистое увеличение прибыли каждой фирмы при различных сценариях развития событий:

| Выплаты, млн USD | Фирма B | |||

| Убрать рекламу | Ничего не менять | Увеличить рекламу | ||

| Фирма A | Убрать рекламу | 80, 100 | -10, 90 | -50, 80 |

| Ничего не менять | 100, 60 | 0, 20 | 30, 50 | |

| Увеличить рекламу | 150, 20 | 130, 50 | 50, 20 |

В этой игре есть доминирующая стратегия для фирмы A, то есть для рекламы. Это происходит потому, что максимальный выигрыш для игрока, указанного в строке, во всех столбцах отображается в последней строке.

Фирма B не имеет доминирующей стратегии, потому что ее максимальный выигрыш не происходит в одной и той же колонке. Когда фирма A сокращает рекламный бюджет, максимальный выигрыш для фирмы В наступает, когда она следует той же стратегии.

Точно так же, когда фирма A не меняет рекламный бюджет, фирма B добивается максимального выигрыша, сокращая рекламу. Но если фирма А увеличивает расходы на рекламу, лучшей стратегией фирмы B является сохранение текущего рекламного бюджета.

Нет доминирующей стратегии и для фирмы B, потому что нет столбца, в котором ее выигрыш всегда был бы наихудшим.

Равновесие Нэша должно проявлять себя в последнем ряду, отражающем доминирующую стратегию фирмы А. Равновесие Нэша в этой игре будет достигнуто, когда фирма A рекламирует.

Нужно найти, какая ячейка дает максимальный выигрыш для фирмы B в последней строке. Это вторая колонка, которая представляет фирму B, не меняющую рекламный бюджет.

Строка 3 и столбец 2, следовательно, показывают равновесие Нэша, потому что:

[1] фирма A не имеет стимула менять стратегию, так как увеличение рекламы является ее доминирующей стратегией;

[2] поскольку фирма A будет рекламировать в любом случае, лучший ответ фирмы B – не менять бюджет, потому что это дает ей максимальную отдачу.

Если фирма B сократит рекламный бюджет или увеличит его, ее выигрыш упадет до 20 миллионов долларов в каждом случае, что хуже, чем 50 миллионов долларов, которые она получит при другом сценарии.

Текущая версия страницы пока не проверялась опытными участниками и может значительно отличаться от версии, проверенной 9 сентября 2020 года; проверки требуют 11 правок.

| Равновесие Нэша | |

|---|---|

| Концепция решения в теории игр | |

| Связанные множества решений | |

| Надмножества |

Рационализируемость Коррелированное равновесие ε-равновесие |

| Подмножества |

Равновесие, совершенное по подыграм Равновесие дрожащей руки Эволюционно стабильная стратегия Сильное равновесие |

| Факты | |

| Авторство | Джон Нэш |

| Применение | Все некооперативные игры |

Равнове́сие Нэ́ша — концепция решения, одно из ключевых понятий теории игр. Так называется набор стратегий в игре для двух и более игроков, в котором ни один участник не может увеличить выигрыш, изменив свою стратегию, если другие участники своих стратегий не меняют[1]. Джон Нэш доказал существование такого равновесия в смешанных стратегиях в любой конечной игре.

История[править | править код]

Эта концепция впервые использована Антуаном Огюстом Курно. Он показал, как найти то, что мы называем равновесием Нэша, в игре Курно. Нэш первым доказал, что подобные равновесия должны существовать для всех конечных игр с любым числом игроков. Это было сделано в его диссертации по некооперативным играм в 1950 году.

До Нэша это было доказано только для игр с 2 участниками с нулевой суммой Джоном фон Нейманом и Оскаром Моргенштерном (1947).

Математическая формулировка[править | править код]

Соотношение равновесных концепций решения. Стрелками обозначено направление от рафинирований к менее требовательным концепциям

Допустим,

Игра может иметь равновесие Нэша в чистых стратегиях или в смешанных (то есть при выборе чистой стратегии стохастически с фиксированной частотой). Нэш доказал, что если разрешить смешанные стратегии, тогда в каждой игре n игроков будет хотя бы одно равновесие Нэша.

Примеры использования понятия[править | править код]

Социология[править | править код]

В социологической теории рационального выбора отдельно подчёркивается, что устойчивое состояние общества (социальное равновесие) может отличаться от оптимального (социальный оптимум). Такие неоптимальные, но устойчивые состояния и называют в социологии равновесием Нэша.

| Актор B | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Актор A | 1 | A: +1, B: +1 | A: −1, B: +2 |

| 2 | A: +2, B: −1 | A: 0, B: 0 |

В таблице слева приведена структура действия в терминах теории игр, составленная для двух действующих субъектов (акторов). Каждый актор имеет два варианта действия, обозначенных цифрами 1 и 2. Коэффициенты вознаграждения получаемые ими при выборе определённых вариантов действия указаны в соответствующих ячейках таблицы. Предположим, что в данный момент оба актора используют действие 2, а их вознаграждения соответственно равны нулю. Выбрав действие 1, актор A ухудшит собственную ситуацию на одну позицию (A: −1, B: +2). Аналогично актор B самостоятельно выбрав вариант 1, в то время когда актор A продолжает использовать действие 2, только ухудшит свою ситуацию (A: +2, B: −1). Таким образом, несмотря на то, что оба актора понимают, что оптимальным для них была бы ситуация, когда оба они используют действие 1 (вознаграждение — A: +1, B: +1), ни у одного из них нет мотива к изменению ситуации, а равновесие становится результатом отсутствия таких мотивов. Если система уже находится в оптимальном состоянии (когда оба актора выбрали действие 1), то у обоих из них всегда будет искушение начать использовать действие 2, которое принесёт им вознаграждение за счёт другого игрока. Этот пример иллюстрирует возможность существования двух социальных состояний: устойчивого, но неоптимального (оба актора используют вариант 2); а также второго оптимального, но неустойчивого (оба актора используют вариант 1).[2]

Политология[править | править код]

Для объяснения различных явлений в политической теории часто используется понятие ядра́, являющееся более слабым вариантом равновесия Нэша. Ядром называют набор состояний, в каждом из которых ни одна группа акторов, способных выстроить новое (отсутствующее в данном ядре) состояние, не улучшит своей ситуации по сравнению с их состоянием в данном ядре.[2]

Экономика[править | править код]

В отрасли имеются две фирмы № 1 и № 2. Каждая из фирм может установить два уровня цен: «высокие» и «низкие». Если обе фирмы выберут высокие цены, то каждая будет иметь прибыль по 3 млн. Если обе выберут низкие, то каждая получит по 2 млн. Однако, если одна выберет высокие, а другая низкие, то вторая получит 4 млн, а первая только 1 млн. Наиболее выигрышный в сумме вариант — одновременный выбор высоких цен (сумма = 6 млн). Однако это состояние (при отсутствии картельного сговора) нестабильно из-за возможности относительного выигрыша, которая открывается перед фирмой, отступившей от этой стратегии. Поэтому обе компании с наибольшей вероятностью выберут низкие цены. Хотя этот вариант и не даёт максимального суммарного выигрыша (сумма = 4 млн), он исключает относительный выигрыш конкурента, который тот мог бы получить за счёт отступления от взаимно-оптимальной стратегии. Такая ситуация и называется «равновесием по Нэшу»[3].

В модели олигополии Штакельберга для двух фирм-участников бескоалиционной игры можно принять, что существует две стратегии: 1. дуополист Курно (K) и дуополист Штакельберга (S), то есть S-стратег. Таким образом для двух игроков возможны следующие стратегии:

(K1;K2) (K1;S2);(K2;S1);(S1;S2). Как следует из построения модели прибыль при выборе стратегии S:

Военное дело[править | править код]

Концепция взаимного гарантированного уничтожения. Ни одна из сторон, владеющих ядерным оружием, не может ни безнаказанно начать конфликт, ни разоружиться в одностороннем порядке.

См. также[править | править код]

- Эффективность по Парето

- Парадокс Бертрана

- Эволюционно стабильная стратегия

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Univertv — Равновесие Нэша: шоппинг, репутация, голосование Архивная копия от 13 декабря 2009 на Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 1 2 Джеймс С. Коулман. Экономическая социология с точки зрения теории рационального выбора // Экономическая социология : электронный журнал. — 2004. — Т. 5, № 3. — С. 35—44.

- ↑ «Nash’s Nobel prize» Архивная копия от 26 мая 2015 на Wayback Machine, The Economist, 24 May 2015.

Литература[править | править код]

- Васин А. А., Морозов Теория игр и модели математической экономики. — М.: МГУ, 2005, 272 с. ISBN 5-317-01388-7.

- Воробьёв Н. Н. Теория игр для экономистов-кибернетиков. — М.: Наука, 1985

- Мазалов В. В. Математическая теория игр и приложения. — Изд-во Лань, 2010, 446 с.

- Петросян Л. А., Зенкевич Н. А., Шевкопляс Е. В. Теория игр. — СПб: БХВ-Петербург, 2012, 432 с.

Открыть эту статью в PDF

Определение

Равновесие Нэша — концепция теории игр, в которой оптимальным исходом считается отсутствие стимула отклоняться от первоначальной выбранной стратегии всеми участниками. Проще говоря, ни один игрок не может получить дополнительную выгоду от своих измененных действий, если другие игроки продолжают свои стратегии. Достичь желаемого результата можно только не отклоняясь от первоначальной стратегии.

Равновесие Нэша не всегда оптимальная стратегия. Причина, по которой оно считается ценным понятием теории игр, — в обширной области применения: от экономики до социальных наук.

Математическая запись равновесия Нэша

Математически равновесие Нэша можно записать следующим образом:

ui (s*i, s*-i) ≥ ui (s*i, s*-i) для всех si ∈ Si,

где:

Si — набор всех возможных стратегий для игрока i,

Игрок i = 1, …, N,

s* = (s*i, s*-i) — профиль стратегии или набор из одной стратегии для каждого игрока,

s*-i — обозначает (N – 1) стратегии всех игроков, кроме i-го игрока,

ui (s*i, s*-i) — i-ый игрок с выигрышем в зависимости от стратегии.

Пример равновесия Нэша

Допустим, играют два игрока: X и Y. Каждый может выбрать стратегию А, чтобы получить 1 рубль, или стратегию Б, чтобы проиграть 1 рубль. Следуя логике оба игрока, захотят выбрать стратегию А и получить 1 рубль: (1; 1).

| Игрок X | |||

| Игрок Y | Стратегия А | Стратегия Б | |

| Стратегия А | 1; 1 | 1; -1 | |

| Стратегия Б | -1; 1 | 0; 0 |

Если один игрок, например, игрок Y, выбирает стратегию Б, то он проигрывает 1 рубль, а игрок X выбирает стратегию А, то он выигрывает 1 рубль, и это можно будет записать, как (-1; 1). Точно также будет наоборот, если игрок Y выберет стратегию А, а игрок X выберет стратегию Б. Если оба игрока выбирают стратегию Б, то они оба проигрывают, то есть остаются в нулях: (0; 0).

Дилемма заключенного и равновесие Нэша

Допустим два преступника арестованы и не имеют возможности общаться и сговориться, потому что сидят в разных камерах. Как полицейским получить показания? Полиция предлагает каждому заключенному возможность либо предать другого, рассказав о его преступлении, либо сохранять молчание.

| Заключенный № 1 | |||

| Заключенный № 2 | Признаться | Не признаться | |

| Признаться | -5; -5 | -1; -10 | |

| Не признаться | -10; -1 | -1; -1 |

Если оба заключенных предают друг друга, то каждый из них получает 5 лет тюрьмы: (-5; -5).

Если заключенный № 1 предает заключенного № 2, а заключенный № 2 по-прежнему хранит молчание, то он окажется в худшем положении и получит 10 лет тюрьмы. А заключенный № 1 получит всего 1 год тюрьмы: (-10; -1).

Если оба заключенных молчат и не признаются, то каждый из них получит только 1 год тюрьмы: (-1; -1).

Равновесие Нэша в этом примере состоит в том, что оба игрока друг друга предадут. Хотя однозначно, взаимное сотрудничество для обоих наиболее выгодный вариант.

Важность равновесия Нэша

Важность равновесия Нэша — в определении для игрока наилучшего выигрыша в ситуации, основываясь не только на своих решениях, но и на решениях других игроков. Равновесие Нэша используют как в бизнес-, так и в военных стратегиях, в социальных науках и др.

Ограничения равновесия Нэша

Главное ограничение концепции в том, что игрок должен знать стратегию своего противника. Равновесие Нэша возникает тогда, когда игрок решает остаться со своей текущей стратегией, если он знает стратегию противника. В большинстве случаев человек редко знает стратегию противника или то, каким он хочет видеть результат. Равновесие Нэша не всегда приводит к оптимальному результату. Однако дает возможность принять наилучшую стратегию на основе имеющейся информации.

Еще один важный недостаток равновесия Нэша: нет анализа прошлых игр, нет предсказания будущих. Равновесие Нэша не принимает во внимание прошлое поведение игроков, хотя они могут быть одними и теми же. Учитывание прошлого поведения часто предсказывает поведение в будущем.

История равновесия Нэша

Термин «равновесие Нэша» появился в честь американского математика Джона Форбса Нэша-младшего. В 1950 году Джон Нэш защитил диссертацию на тему некооперативных игр, содержащую определение и свойства равновесия Нэша. В диссертации было всего 28 страниц, возраст диссертанта — 22 года. Позднее, в 1994 году, данный вклад в теорию игр принес Джону Нэшу Нобелевскую премию в области экономических наук.

Учёный сделал большой вклад как в математику, так и в экономику. Например, в экономике он работал над темой роли денег в обществе, глобальной системой индекса цен промышленного потребления и другими. Джон Нэш получил множество наград и почетных степеней, стал известен научной мировой общественности. Умер в 86 лет в автокатастрофе по дороге из аэропорта домой, в США, возвращаясь с церемонии награждения премией Абеля в Осло (премией Абеля награждают выдающихся математиков).

Основные работы Джона Нэша, относящиеся к концепции равновесия Нэша:

- «Точки равновесия в играх n-персон», 1950

- «Проблема торга», 1950

- «Некооперационные игры», 1951

- «Кооперативные игры для двух человек», 1953

Такие статьи мы публикуем регулярно. Чтобы получать информацию о новых материалах, а также быть в курсе учебных программ, вы можете подписаться на новостную рассылку.

Если вам необходимо отработать определенные навыки в области инвестиционного или финансового анализа и планирования, посмотрите программы наших семинаров.

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}sigma ^{*}=f(sigma ^{*})&Rightarrow sigma _{i}^{*}=f_{i}(sigma ^{*})\&Rightarrow sigma _{i}^{*}={frac {g_{i}(sigma ^{*})}{sum _{ain A_{i}}g_{i}(sigma ^{*})(a)}}\[6pt]&Rightarrow sigma _{i}^{*}={frac {1}{C}}left(sigma _{i}^{*}+{text{Gain}}_{i}(sigma ^{*},cdot )right)\[6pt]&Rightarrow Csigma _{i}^{*}=sigma _{i}^{*}+{text{Gain}}_{i}(sigma ^{*},cdot )\&Rightarrow left(C-1right)sigma _{i}^{*}={text{Gain}}_{i}(sigma ^{*},cdot )\&Rightarrow sigma _{i}^{*}=left({frac {1}{C-1}}right){text{Gain}}_{i}(sigma ^{*},cdot ).end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/556e976617ee74da95e980547e8d4f7a1aef701c)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for A playing H}}]=(-1)q+(+1)(1-q)=1-2q\&mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for A playing T}}]=(+1)q+(-1)(1-q)=2q-1\&mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for A playing H}}]=mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for A playing T}}]implies 1-2q=2q-1implies q={frac {1}{2}}\&mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for B playing H}}]=(+1)p+(-1)(1-p)=2p-1\&mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for B playing T}}]=(-1)p+(+1)(1-p)=1-2p\&mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for B playing H}}]=mathbb {E} [{text{payoff for B playing T}}]implies 2p-1=1-2pimplies p={frac {1}{2}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2eb56208b46327ad1d4aba30ca5f8d81a22a043f)