The reason why you always got True has already been given, so I’ll just offer another suggestion:

If your file is not too large, you can read it into a string, and just use that (easier and often faster than reading and checking line per line):

with open('example.txt') as f:

if 'blabla' in f.read():

print("true")

Another trick: you can alleviate the possible memory problems by using mmap.mmap() to create a “string-like” object that uses the underlying file (instead of reading the whole file in memory):

import mmap

with open('example.txt') as f:

s = mmap.mmap(f.fileno(), 0, access=mmap.ACCESS_READ)

if s.find('blabla') != -1:

print('true')

NOTE: in python 3, mmaps behave like bytearray objects rather than strings, so the subsequence you look for with find() has to be a bytes object rather than a string as well, eg. s.find(b'blabla'):

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import mmap

with open('example.txt', 'rb', 0) as file,

mmap.mmap(file.fileno(), 0, access=mmap.ACCESS_READ) as s:

if s.find(b'blabla') != -1:

print('true')

You could also use regular expressions on mmap e.g., case-insensitive search: if re.search(br'(?i)blabla', s):

In this Python tutorial, you’ll learn to search a string in a text file. Also, we’ll see how to search a string in a file and print its line and line number.

After reading this article, you’ll learn the following cases.

- If a file is small, read it into a string and use the

find()method to check if a string or word is present in a file. (easier and faster than reading and checking line per line) - If a file is large, use the mmap to search a string in a file. We don’t need to read the whole file in memory, which will make our solution memory efficient.

- Search a string in multiple files

- Search file for a list of strings

We will see each solution one by one.

Table of contents

- How to Search for a String in Text File

- Example to search for a string in text file

- Search file for a string and Print its line and line number

- Efficient way to search string in a large text file

- mmap to search for a string in text file

- Search string in multiple files

- Search file for a list of strings

How to Search for a String in Text File

Use the file read() method and string class find() method to search for a string in a text file. Here are the steps.

- Open file in a read mode

Open a file by setting a file path and access mode to the

open()function. The access mode specifies the operation you wanted to perform on the file, such as reading or writing. For example, r is for reading.fp= open(r'file_path', 'r') - Read content from a file

Once opened, read all content of a file using the

read()method. Theread()method returns the entire file content in string format. - Search for a string in a file

Use the

find()method of a str class to check the given string or word present in the result returned by theread()method. Thefind()method. The find() method will return -1 if the given text is not present in a file - Print line and line number

If you need line and line numbers, use the

readlines() method instead ofread()method. Use the for loop andreadlines()method to iterate each line from a file. Next, In each iteration of a loop, use the if condition to check if a string is present in a current line and print the current line and line number

Example to search for a string in text file

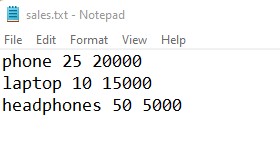

I have a ‘sales.txt’ file that contains monthly sales data of items. I want the sales data of a specific item. Let’s see how to search particular item data in a sales file.

def search_str(file_path, word):

with open(file_path, 'r') as file:

# read all content of a file

content = file.read()

# check if string present in a file

if word in content:

print('string exist in a file')

else:

print('string does not exist in a file')

search_str(r'E:demosfiles_demosaccountsales.txt', 'laptop')Output:

string exists in a file

Search file for a string and Print its line and line number

Use the following steps if you are searching a particular text or a word in a file, and you want to print a line number and line in which it is present.

- Open a file in a read mode.

- Next, use the

readlines()method to get all lines from a file in the form of a list object. - Next, use a loop to iterate each line from a file.

- Next, In each iteration of a loop, use the if condition to check if a string is present in a current line and print the current line and line number.

Example: In this example, we’ll search the string ‘laptop’ in a file, print its line along with the line number.

# string to search in file

word = 'laptop'

with open(r'E:demosfiles_demosaccountsales.txt', 'r') as fp:

# read all lines in a list

lines = fp.readlines()

for line in lines:

# check if string present on a current line

if line.find(word) != -1:

print(word, 'string exists in file')

print('Line Number:', lines.index(line))

print('Line:', line)Output:

laptop string exists in a file line: laptop 10 15000 line number: 1

Note: You can also use the readline() method instead of readlines() to read a file line by line, stop when you’ve gotten to the lines you want. Using this technique, we don’t need to read the entire file.

Efficient way to search string in a large text file

All above way read the entire file in memory. If the file is large, reading the whole file in memory is not ideal.

In this section, we’ll see the fastest and most memory-efficient way to search a string in a large text file.

- Open a file in read mode

- Use for loop with

enumerate()function to get a line and its number. Theenumerate()function adds a counter to an iterable and returns it in enumerate object. Pass the file pointer returned by theopen()function to theenumerate(). - We can use this enumerate object with a for loop to access the each line and line number.

Note: The enumerate(file_pointer) doesn’t load the entire file in memory, so this is an efficient solution.

Example:

with open(r"E:demosfiles_demosaccountsales.txt", 'r') as fp:

for l_no, line in enumerate(fp):

# search string

if 'laptop' in line:

print('string found in a file')

print('Line Number:', l_no)

print('Line:', line)

# don't look for next lines

breakExample:

string found in a file Line Number: 1 Line: laptop 10 15000

mmap to search for a string in text file

In this section, we’ll see the fastest and most memory-efficient way to search a string in a large text file.

Also, you can use the mmap module to find a string in a huge file. The mmap.mmap() method creates a bytearray object that checks the underlying file instead of reading the whole file in memory.

Example:

import mmap

with open(r'E:demosfiles_demosaccountsales.txt', 'rb', 0) as file:

s = mmap.mmap(file.fileno(), 0, access=mmap.ACCESS_READ)

if s.find(b'laptop') != -1:

print('string exist in a file')Output:

string exist in a file

Search string in multiple files

Sometimes you want to search a string in multiple files present in a directory. Use the below steps to search a text in all files of a directory.

- List all files of a directory

- Read each file one by one

- Next, search for a word in the given file. If found, stop reading the files.

Example:

import os

dir_path = r'E:demosfiles_demosaccount'

# iterate each file in a directory

for file in os.listdir(dir_path):

cur_path = os.path.join(dir_path, file)

# check if it is a file

if os.path.isfile(cur_path):

with open(cur_path, 'r') as file:

# read all content of a file and search string

if 'laptop' in file.read():

print('string found')

breakOutput:

string found

Search file for a list of strings

Sometimes you want to search a file for multiple strings. The below example shows how to search a text file for any words in a list.

Example:

words = ['laptop', 'phone']

with open(r'E:demosfiles_demosaccountsales.txt', 'r') as f:

content = f.read()

# Iterate list to find each word

for word in words:

if word in content:

print('string exist in a file')Output:

string exist in a file

Python Exercises and Quizzes

Free coding exercises and quizzes cover Python basics, data structure, data analytics, and more.

- 15+ Topic-specific Exercises and Quizzes

- Each Exercise contains 10 questions

- Each Quiz contains 12-15 MCQ

Improve Article

Save Article

Like Article

Improve Article

Save Article

Like Article

In this article, we are going to see how to search for a string in text files using Python

Example:

string = “GEEK FOR GEEKS”

Input: “FOR”

Output: Yes, FOR is present in the given string.

Text File for demonstration:

myfile.txt

Finding the index of the string in the text file using readline()

In this method, we are using the readline() function, and checking with the find() function, this method returns -1 if the value is not found and if found it returns 0.

Python3

with open(r'myfile.txt', 'r') as fp:

lines = fp.readlines()

for row in lines:

word = 'Line 3'

if row.find(word) != -1:

print('string exists in file')

print('line Number:', lines.index(row))

Output:

string exists in file line Number: 2

Finding string in a text file using read()

we are going to search string line by line if the string is found then we will print that string and line number using the read() function.

Python3

with open(r'myfile.txt', 'r') as file:

content = file.read()

if 'Line 8' in content:

print('string exist')

else:

print('string does not exist')

Output:

string does not exist

Search for a String in Text Files using enumerate()

We are just finding string is present in the file or not using the enumerate() in Python.

Python3

with open(r"myfile.txt", 'r') as f:

for index, line in enumerate(f):

if 'Line 3y' in line:

print('string found in a file')

break

print('string does not exist in a file')

Output:

string does not exist in a file

Last Updated :

14 Mar, 2023

Like Article

Save Article

In this article, we will learn to search and replace a text of a file in Python. We will use some built-in functions and some custom codes as well. We will replace text, or strings within a file using mentioned ways.

Python provides multiple built-in functions to perform file handling operations. Instead of creating a new modified file, we will search a text from a file and replace it with some other text in the same file. This modifies the file with new data. This will replace all the matching texts within a file and decreases the overhead of changing each word. Let us discuss some of the mentioned ways to search and replace text in a file in Python.

Sample Text File

We will use the below review.text file to modify the contents.

In the movie Ghost

the joke is built on a rock-solid boundation

the movie would still work played perfectly straight

The notion of a ghost-extermination squad taking on

the paramal hordes makes a compelling setup for a big-budget adventure of any stripe

Indeed, the film as it stands frequently allows time to pass without a gag

But then comes the punch line: the characters are funny

And because we’ve been hooked by the story, the humor the characters provide is all the richer.Example: Use replace() to Replace a Text within a File

The below example uses replace() function to modify a string within a file. We use the review.txt file to modify the contents. It searches for the string by using for loop and replaces the old string with a new string.

open(file,'r') – It opens the review.txt file for reading the contents of the file.

strip() – While iterating over the contents of the file, strip() function strips the end-line break.

replace(old,new) – It takes an old string and a new string to replace its arguments.

file.close() – After concatenating the new string and adding an end-line break, it closes the file.

open(file,'w') – It opens the file for writing and overwrites the old file content with new content.

reading_file = open("review.txt", "r")

new_file_content = ""

for line in reading_file:

stripped_line = line.strip()

new_line = stripped_line.replace("Ghost", "Ghostbusters")

new_file_content += new_line +"n"

reading_file.close()

writing_file = open("review.txt", "w")

writing_file.write(new_file_content)

writing_file.close()Output:

Example: Replace a Text using Regex Module

An alternative method to the above-mentioned methods is to use Python’s regex module. The below example imports regex module. It creates a function and passed a file, an old string, and a new string as arguments. Inside the function, we open the file in both read and write mode and read the contents of the file.

compile() – It is used to compile a regular expression pattern and convert it into a regular expression object which can then be used for matching.

escape() – It is used to escape special characters in a pattern.

sub() – It is used to replace a pattern with a string.

#importing the regex module

import re

#defining the replace method

def replace(filePath, text, subs, flags=0):

with open(file_path, "r+") as file:

#read the file contents

file_contents = file.read()

text_pattern = re.compile(re.escape(text), flags)

file_contents = text_pattern.sub(subs, file_contents)

file.seek(0)

file.truncate()

file.write(file_contents)

file_path="review.txt"

text="boundation"

subs="foundation"

#calling the replace method

replace(file_path, text, subs)Output:

FileInput in Python

FileInput is a useful feature of Python for performing various file-related operations. For using FileInput, fileinput module is imported. It is great for throwaway scripts. It is also used to replace the contents within a file. It performs searching, editing, and replacing in a text file. It does not create any new files or overheads.

Syntax-

FileInput(filename, inplace=True, backup='.bak')Parameters-

backup – The backup is an extension for the backup file created before editing.

Example: Search and Replace a Text using FileInput and replace() Function

The below function replaces a text using replace() function.

import fileinput

filename = "review.txt"

with fileinput.FileInput(filename, inplace = True, backup ='.bak') as f:

for line in f:

if("paramal" in line):

print(line.replace("paramal","paranormal"), end ='')

else:

print(line, end ='') Output:

Conclusion

In this article, we learned to search and replace a text, or a string in a file by using several built-in functions such as replace(), regex and FileInput module. We used some custom codes as well. We saw outputs too to differentiate between the examples. Therefore, to search and replace a string in Python user can load the entire file and then replaces the contents in the same file instead of creating a new file and then overwrite the file.

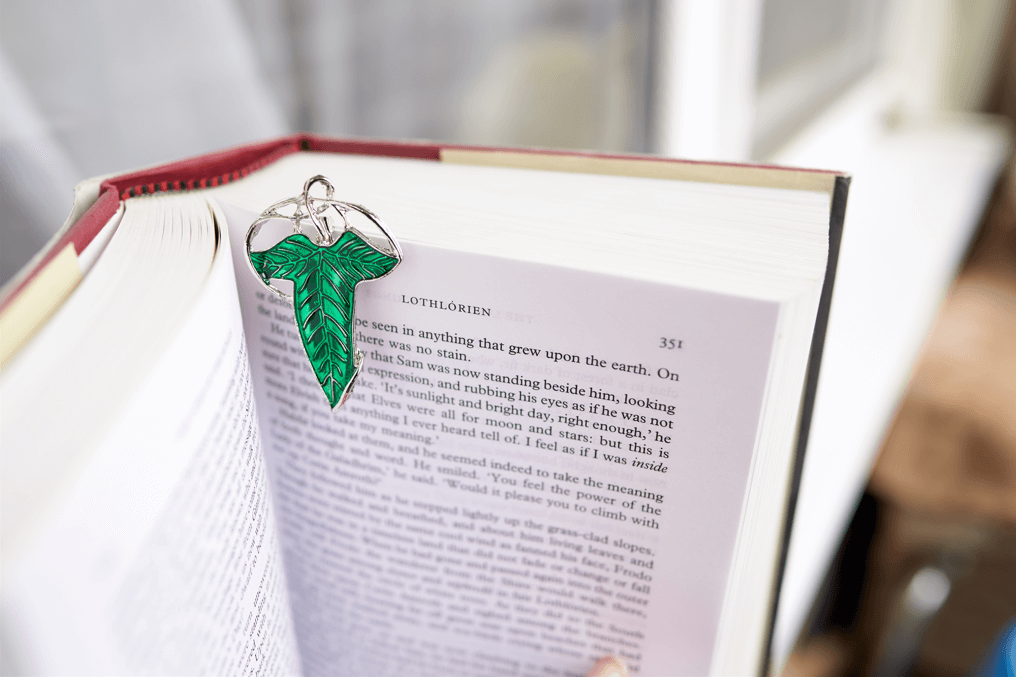

В прошлой статье я рассказывала, что составила для своего проекта словарь «Властелина Колец», причем для каждого англоязычного терма (слова/словосочетания) хранится перевод и список глав, в которых встречается это выражение. Все это составлено вручную. Однако мне не дает покоя, что многие вхождения термов могли быть пропущены.

В первой версии MVP я частично решила эту проблему обычным поиском по подстроке (b{term}, где b – граница слова), что позволило найти вхождения отдельных слов без учета морфологии или с некоторыми внешними флексиями (например, -s, -ed, -ing). Фактически это поиск подстроки с джокером на конце. Но для многословных выражений и неправильных глаголов, составляющих весомую долю моего словаря, этот способ не работал.

После пары безуспешных попыток установить Elasticsearch я, как типичный изобретатель велосипеда и вечного двигателя, решила писать свой код. Скудным словообразованием английского языка меня не запугать ввиду наличия опыта разработки полнотекстового поиска по документам на великом и могучем русском языке. Кроме того, для моей задачи часть вхождений уже все равно выбрана вручную и потому стопроцентная точность не требуется.

Подготовка словаря

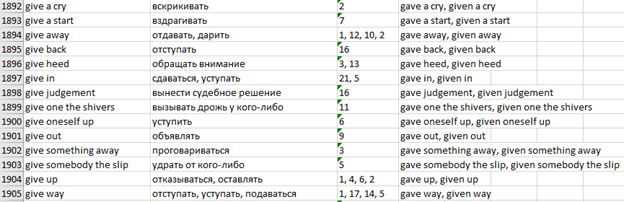

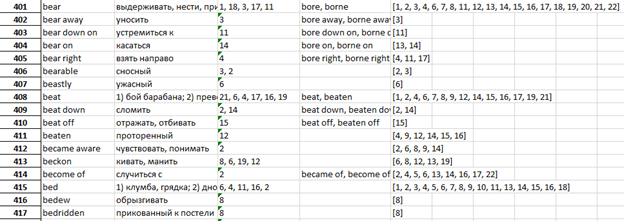

Итак, дан словарь. Ну как дан – составлен руками за несколько месяцев упорного труда. Дан с точки зрения программиста. После прошлой статьи словарь подрос вдвое и теперь охватывает весь первый том («Братство Кольца»). В сыром виде состоит из 11.690 записей в формате «терм – перевод – номер главы». Хранится в Excel.

Как и в прошлый раз, я сгруппировала свой словарь по словарным гнездам с помощью функции pivot_table() из pandas. Осталось 5.404 записи, а после ручного редактирования – 5.354.

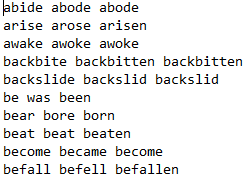

Больше всего меня беспокоили неправильные глаголы, поскольку в моем словаре они хранились в инфинитиве, а в романе чаще всего употреблялись в прошедшем времени. Ввиду так называемого аблаута (например, run – ran – run) установить инфинитив по словоформе прошедшего времени невозможно.

Я скачала словарь неправильных глаголов. Он насчитывал 294 штуки, многие из которых допускали два варианта. Пришлось проверить все вариации по тексту Толкиена, чтобы установить, какая форма характерна для его речи: например, cloven (p.p. от cleave) вместо cleft (что у него существительное). Оказалось, что многие неправильные глаголы у него правильные (например, burn), а leap даже существует в обеих версиях – leaped и leapt.

Теперь вариации неправильных глаголов унифицированы, а их список хранится в обычном текстовом файле:

Остается считать этот файл в датафрейм с помощью функции read_csv(), указав в качестве разделителей пробелы:

import pandas as pd

verb_data = pd.read_csv(pathlib.Path('c:/', 'ALL', 'LotR', 'неправильные глаголы.txt'),

sep=" ", header=None, names=["Inf", "Past", "PastParticiple"], index_col=0)Явно задаем index_col, чтобы сделать индексом первый столбец, хранящий инфинитивы глаголов, для удобства дальнейшего поиска.

Считаем наш главный словарь в другой датафрейм:

excel_data = pd.read_excel(pathlib.Path('c:/', 'ALL', 'LotR', 'словарь Толкиена сведенный.xlsx'), dtype = str)

df = pd.DataFrame(excel_data, columns=['Word', 'Russian', 'Chapters'])Теперь объявим функцию, которая для каждого словарного терма проверит наличие в нем неправильного глагола и в зависимости от результата сгенерирует словоформы. Для простоты будем считать, что неправильный глагол всегда стоит на первом месте.

def check_irrverbs(word):

global verb_data

# берем часть выражения до первого пробела

arr = word.split(' ')

w, *tail = arr # = arr[0], arr[1:]

# запоминаем хвост

tail = " ".join(tail)

# проверяем, не является ли она неправильным глаголом

if w in verb_data.index:

# формируем формы Past и Past Participle

# если они одинаковые, то достаточно хранить одну форму

if verb_data.loc[w]["Past"] == verb_data.loc[w]["PastParticiple"]:

return verb_data.loc[w]["Past"] + " " + tail

return ", ".join([v + " " + tail for v in verb_data.loc[w].tolist()])

return ""Таким образом, для выражения make up one’s mind функция вернет made up one’s mind.

Применяем функцию к датафрейму, сохраняя результаты в новый столбец, и затем экспортируем результат в новый Excel-файл:

df['IrrVerb'] = df['Word'].apply(check_irrverbs)

df.to_excel(pathlib.Path('c:/', 'ALL', 'LotR', 'словарь Толкиена сведенный.xlsx'))Теперь в Excel-таблице появился новый столбец, хранящий 2-ю (Past) и 3-ю (Past Participle) формы для всех неправильных глаголов, а для правильных столбец пуст.

Всего таких записей оказалось 662.

Спряжение потенциальных глаголов

Теперь сгенерируем все формы и для правильных, и для неправильных глаголов.

def generate_verbs(word, is_irrverb):

forms = []

# взять часть выражения до первого пробела

verb, tail = word, ""

pos = word.find(" ")

if pos >= 0:

verb = word[:pos]

tail = word[pos:]

consonant = "bcdfghjklmnpqrstvwxz"

last = verb[-1]

# глагол во 2 и 3 формах

if not is_irrverb:

if last in consonant:

forms.append(verb + last + "ed" + tail) # stop -> stopped

forms.append(verb + "ed" + tail) # и вариант без удвоения

elif last == "y":

if verb[-2] in consonant:

forms.append(verb[:-1] + "ied" + tail) # carry -> carried

else:

forms.append(verb + "ed" + tail) # play -> played

elif last == "e":

forms.append(verb + "d" + tail) # arrive -> arrived

else:

forms.append(verb + "ed" + tail)

# герундий, он же ing-овая форма глагола

if verb[-2:] == "ie":

forms.append(verb[:-2] + "ying" + tail) # lie -> lying

elif last == "e":

forms.append(verb[:-1] + "ing" + tail) # write -> writing

elif last in consonant:

forms.append(verb + last + "ing" + tail) # sit -> sitting

forms.append(verb + "ing" + tail) # sit -> sitting

else:

forms.append(verb + "ing" + tail)

return formsКак и прежде, для простоты будем считать глаголом часть выражения до первого пробела либо все выражение целиком, если оно не содержит пробелов. Посмотрим, на какую букву (переменная last) оканчивается предполагаемый глагол. Для этого нужен список либо гласных, либо согласных. Список гласных был бы короче, но так как нам понадобится проверять именно на согласную, то нагляднее будет хранить список consonant.

Для правильных глаголов вторая и третья формы создаются путем прибавления флексий -d, -ed, -ied в зависимости от последнего и предпоследнего звука. Так как учитывается еще и ударение, то проще всего сгенерировать оба варианта, из которых грамматически корректен будет только один. Для неправильных глаголов мы уже нашли обе формы и записали в отдельный столбец.

Герундий образуется одинаково для правильных и неправильных глаголов, но опять-таки надо учитывать последний символ и ударение, поэтому снова создаем оба варианта.

Все варианты записываются в список forms, который функция и возвращает.

Сложность заключается в том, что наш словарь не содержит информации о частях речи для каждого терма, да это и малоинформативно ввиду так называемой конверсии – одно и то же слово может быть и существительным, и глаголом в зависимости от места в предложении. Поэтому мы сейчас рассматриваем все хранящиеся в словаре выражения как потенциальные глаголы, так как перед нами не стоит задача построить грамматически корректную форму. Мы строим просто гипотезы. Если они не найдутся в тексте, то и не надо.

Подстановки

Кроме неправильных глаголов, словарь содержит еще один вид выражений, осложняющих полнотекстовый поиск, – подстановочные местоимения: притяжательное one’s, возвратное oneself и неопределенные somebody и something. В реальном тексте они должны заменяться на конкретные слова – соответственно, притяжательные местоимения (my, your, his и т.д.), возвратные местоимения (myself, yourself, himself и т.д.) и существительные. Поэтому надо сгенерировать все возможные формы с подстановками.

Начнем с one’s и oneself:

def replace_possessive_reflexive(word):

possessive = ["my", "mine", "your", "yours", "his", "her", "hers", "its", "our", "ours", "their", "theirs"]

reflexive = ["myself", "yourself", "himself", "herself", "itself", "ourselves", "yourselves", "themselves"]

# заменить one's на все варианты из possessive

if "one's" in word:

forms = list(map(lambda p: word.replace("one's", p), possessive))

elif "oneself" in word:

# заменить oneself на все варианты из reflexive

forms = list(map(lambda r: word.replace("oneself", r), reflexive))

else:

forms = [word]

return formsЗдесь мы для простоты предполагаем, что one’s и oneself не встречаются в одном выражении, а также не употребляются в реальном тексте. Если в терме есть одно из этих слов, то он интересует нас только с подстановками. В противном случае терм рассматривается как одна из форм самого себя, поэтому создается список, состоящий только из него.

Полный процесс замены обрабатывает также скобки и неопределенные местоимения:

def template_replace(word):

forms = []

forms = [word] if not "(" in word else [word.replace("(", "").replace(")", ""), re.sub("([^)]+)", "", word)]

forms = list(map(lambda f: f.replace("somebody", "S+").replace("something", "S+"), forms))

forms = list(map(replace_possessive_reflexive, forms))

return sum(forms, [])Замена происходит в три этапа, причем результат предыдущего подается на вход следующему.

-

Если терм содержит скобки, то рассматриваем два варианта – с их содержимым или без него: например, wild(ly) -> {wild, wildly}.

-

Что касается somebody и something, то они заменяются на S+ – группу любых непробельных символов, то есть на заготовку для будущего регулярного выражения.

-

Наконец вызываем рассмотренную выше функцию replace_possessive_reflexive() для обработки one’s и oneself.

В итоге получится многомерный список, который необходимо преобразовать в одномерный. В данном случае эта задача решается путем сложения с пустым списком.

Таким образом, основная идея данной реализации полнотекстового поиска – генерировать максимальное количество вариантов словоформ, чтобы затем искать их в тексте. Как велико это число? В простейшем случае, для термов, не содержащих неправильных глаголов и оканчивающихся на гласную, будет всего 3 формы – инфинитив, вторая/третья форма и герундий. Если терм кончается на согласную, то появляется второй вариант герундия. В худшем случае терм содержит скобки, притяжательное местоимение и неправильный глагол, оканчиваясь на согласную, тогда для первичного списка из 2 вариантов со скобками * 12 притяжательных местоимений будут сгенерированы по 24 формы инфинитива, двух вариантов герундия, а также прошедшего времени и причастия прошедшего времени, итого

Отдельной строкой, чтобы осознать масштаб этой цифры)

Впрочем, мой словарь не содержит настолько сложных случаев. Вот более характерный пример – hold one’s breath (сочетание неправильного глагола, оканчивающегося на гласную, и притяжательного местоимения). Из него будет сгенерировано 48 форм:

-

12 вариантов инфинитива: ‘hold my breath’, ‘hold mine breath’, ‘hold your breath’, ‘hold yours breath’, ‘hold his breath’, ‘hold her breath’, ‘hold hers breath’, ‘hold its breath’, ‘hold our breath’, ‘hold ours breath’, ‘hold their breath’, ‘hold theirs breath’

-

24 варианта герундия, с удвоенной согласной и с одинарной: ‘holdding my breath’, ‘holding my breath’, ‘holdding mine breath’, ‘holding mine breath’, ‘holdding your breath’, ‘holding your breath’, ‘holdding yours breath’, ‘holding yours breath’, ‘holdding his breath’, ‘holding his breath’, ‘holdding her breath’, ‘holding her breath’, ‘holdding hers breath’, ‘holding hers breath’, ‘holdding its breath’, ‘holding its breath’, ‘holdding our breath’, ‘holding our breath’, ‘holdding ours breath’, ‘holding ours breath’, ‘holdding their breath’, ‘holding their breath’, ‘holdding theirs breath’, ‘holding theirs breath’

-

12 вариантов прошедшего времени, совпадающего с past participle: ‘held my breath’, ‘held mine breath’, ‘held your breath’, ‘held yours breath’, ‘held his breath’, ‘held her breath’, ‘held hers breath’, ‘held its breath’, ‘held our breath’, ‘held ours breath’, ‘held their breath’, ‘held theirs breath’

Такие случаи довольно редки. Как уже говорилось, на весь 5-тысячный словарь нашлось всего 662 строки с неправильными глаголами. Что касается остальных сложных случаев, то в словаре 91 терм с притяжательными местоимениями, 31 – с подстановками somebody/something и 61 совмещает в себе и неправильный глагол, и какую-либо подстановку.

Поиск по тексту

Наконец приступаем к анализу оригинального текста, чтобы найти в нем пропущенные вхождения термов. Считаем датафрейм из Excel, не забывая, что заданные в списке columns заголовки столбцов должны фигурировать в первой строке листа Excel.

excel_data = pd.read_excel(pathlib.Path('c:/', 'ALL', 'LotR', 'словарь Толкиена сведенный.xlsx'), dtype = str)

df = pd.DataFrame(excel_data, columns=['Word', 'Russian', 'Chapters', 'IrrVerb'])Прежде чем работать с текстом романа, возьмем на себя смелость слегка подправить великого автора, изменив нумерацию глав на сквозную. Вместо двух книг по 12 и 10 глав соответственно получится одна с 22-мя главами.

После этого откроем текст, удалим символы перевода строки и табуляции. Сразу заменим часто встречающееся в нем слово Mr., чтобы оно не мешало разбивать текст по предложениям.

f = open(pathlib.Path('c:/', 'ALL', 'LotR', 'Fellowship.txt'))

text = f.read().replace('n', ' ').replace('t', ' ').replace('r', ' ').replace('Mr. ', 'Mr') # учтет Mr.BagginsТеперь разобьем текст по главам.

lotr = []

text = re.split('Chaptersd+', text)Тогда в 0-м элементе списка будет предисловие, в 1-м – глава 1 и т.д., то есть индексы будут соответствовать реальным номерам глав, что очень удобно.

for chapter in text:

lotr.append(re.split('[.?!]', chapter))Теперь нас ждет главная функция, обрабатывающая строку датафрейма. Прежде всего получим старый список глав, в которых встречается данный терм. Он хранится в отдельном столбце таблицы. Наша задача – постараться дополнить этот список и в любом случае не забыть хотя бы отсортировать его.

ch = list(map(int, vec[0].split(',')))Если терм оканчивается восклицательным или вопросительным знаком, то это неизменяемое устойчивое выражение, например, междометие. Для него никаких словоформ искать не нужно.

word = vec[1]

if word[-1:] == "!" or word[-1:] == "?":

forms = [word]Для любого другого терма начнем с проверки, входит ли в него неправильный глагол, то есть заполнен ли соответствующий столбец (isnan()). Для неправильного глагола выделим 2-ю и 3-ю формы, которые могут различаться или совпадать.

else:

is_irrverb = False if isinstance(vec[2], float) and math.isnan(vec[2]) else True

if is_irrverb:

pos = vec[2].find(", ")

if pos >= 0:

past = vec[2][:pos]

past_participle = vec[2][pos + 2:]

else:

past = past_participle = vec[2]Произведем замены с помощью функции template_replace(), получим список словоформ. Проспрягаем каждый элемент этого списка.

forms = template_replace(word)

forms = forms + sum(list(map(lambda f: generate_verbs(f, is_irrverb), forms)), [])Для неправильных глаголов отдельно произведем замены для 2-й и 3-й форм.

if is_irrverb:

forms = forms + template_replace(past)

if past_participle != past:

forms = forms + template_replace(past_participle)Затем ищем каждую словоформу в каждой главе кроме ранее найденных глав, содержащихся в старом списке ch. Для этого используем функцию filter(), передав ей лямбда-функцию, которая будет обрабатывать каждое предложение. Поиск производится по регулярному выражению b{f}, где b – граница слова, а f – словоформа. Как уже говорилось, указание левой границы слова позволяет реализовать поиск с джокером на конце подстроки. Несмотря на весь написанный ранее код, мы все еще нуждаемся в этом нехитром приеме, так как флексии никто не отменял. Кроме того, от регулярного выражения мы никуда не денемся, так как ранее заменяли somebody/something на S+.

for f in forms:

for i in range(1, len(lotr)): # 0-ю главу (предисловие) пока пропускаем

if not i in ch:

match = list(filter(lambda sentence: re.search(rf'b{f}', sentence, flags=re.IGNORECASE), lotr[i]))

if match:

ch.append(i)Этот код ищет все вхождения терма в главу, хотя для поставленной задачи нужно найти только первое. Зато этот вариант облегчает тестирование программы.

Новые номера глав сохраняются в тот же список ch, который в конце концов сортируется и возвращается.

ch.sort()

return chПолный код функции check_chapters() выглядит следующим образом.

def check_chapters(vec):

global lotr

ch = list(map(int, vec[0].split(',')))

word = vec[1]

if word[-1:] == "!" or word[-1:] == "?":

forms = [word]

else:

is_irrverb = False if isinstance(vec[2], float) and math.isnan(vec[2]) else True

if is_irrverb:

pos = vec[2].find(", ")

if pos >= 0:

past = vec[2][:pos]

past_participle = vec[2][pos + 2:]

else:

past = past_participle = vec[2]

forms = template_replace(word)

forms = forms + sum(list(map(lambda f: generate_verbs(f, is_irrverb), forms)), [])

if is_irrverb:

forms = forms + template_replace(past)

if past_participle != past:

forms = forms + template_replace(past_participle)

for f in forms:

for i in range(1, len(lotr)): # 0-ю главу (предисловие) пока пропускаем

if not i in ch:

match = list(filter(lambda sentence: re.search(rf'b{f}', sentence, flags=re.IGNORECASE), lotr[i]))

if match:

ch.append(i)

ch.sort()

return chОсталось только применить эту функцию к датафрейму, сохранив результат в новый столбец New chapters:

df['New chapters'] = df[['Chapters', 'Word', 'IrrVerb']].apply(check_chapters, axis=1)

df.to_excel(pathlib.Path('c:/', 'ALL', 'LotR', 'словарь Толкиена сведенный.xlsx'))Тестирование

Для тестирования была произведена выборка наиболее сложных термов – с неправильными глаголами и подстановками.

test = df[['Chapters', 'Word', 'IrrVerb']]

test = test[(test['IrrVerb'].str.len() > 0) & (test['Word'].str.contains("one's") | test['Word'].str.contains("something") | test['Word'].str.contains("somebody"))]

print(test.apply(check_chapters, axis=1))Вот термы, для которых было найдено более одного вхождения и которые поэтому являются самыми характерными (неупорядоченная нумерация сложилась потому, что поиск производился сначала по словоформам и лишь затем по главам):

|

Терм |

Найденные вхождения |

|

find one’s way |

Chapter 12: We could perhaps find our way through and come round to Rivendell from the north; but it would take too long, for I do not know the way, and our food would not last Chapter 2: He found his way into Mirkwood, as one would expect |

|

make one’s way |

Chapter 3: My plan was to leave the Shire secretly, and make my way to Rivendell; but now my footsteps are dogged, before ever I get to Buckland Chapter 16: Make your ways to places where you can find grass, and so come in time to Elrond’s house, or wherever you wish to go Chapter 6: Coming to the opening they found that they had made their way down through a cleft in a high sleep bank, almost a cliff Chapter 11: Merry’s ponies had escaped altogether, and eventually (having a good deal of sense) they made their way to the Downs in search of Fatty Lumpkin Chapter 12: They made their way slowly and cautiously round the south-western slopes of the hill, and came in a little while to the edge of the Road |

|

make up one’s mind |

Chapter 10: You must make up your mind Chapter 19: But before Sam could make up his mind what it was that he saw, the light faded; and now he thought he saw Frodo with a pale face lying fast asleep under a great dark cliff Chapter 16: The eastern arch will probably prove to be the way that we must take; but before we make up our minds we ought to look about us Chapter 22: ‘Yet we must needs make up our minds without his aid Chapter 4: I am leaving the Shire as soon as ever I can – in fact I have made up my mind now not even to wait a day at Crickhollow, if it can be helped Chapter 21: Sam had long ago made up his mind that, though boats were maybe not as dangerous as he had been brought up to believe, they were far more uncomfortable than even he had imagined |

|

one’s heart sink |

Chapter 11: ‘It is getting late, and I don’t like this hole: it makes my heart sink somehow Chapter 14: ” ‘”The Shire,” I said; but my heart sank |

|

shake one’s head |

Chapter 2: ‘They are sailing, sailing, sailing over the Sea, they are going into the West and leaving us,’ said Sam, half chanting the words, shaking his head sadly and solemnly Chapter 4: Too near the River,’ he said, shaking his head Chapter 9: ‘ ‘There’s some mistake somewhere,’ said Butterbur, shaking his head Chapter 14: ‘ he said, shaking his head Chapter 16: ‘I am too weary to decide,’ he said, shaking his head Chapter 12: ‘ When he heard what Frodo had to tell, he became full of concern, and shook his head and sighed Chapter 15: Gimli looked up and shook his head Chapter 22: Sam, who had been watching his master with great concern, shook his head and muttered: ‘Plain as a pikestaff it is, but it’s no good Sam Gamgee putting in his spoke just now |

|

sleep on something |

Chapter 3: ‘Well, see you later – the day after tomorrow, if you don’t go to sleep on the way Chapter 13: His head seemed sunk in sleep on his breast, and a fold of his dark cloak was drawn over his face Chapter 18: I cannot sleep on a perch |

|

spring to one’s feet |

Chapter 2: ’ cried Gandalf, springing to his feet Chapter 11: ‘ asked Frodo, springing to his feet Chapter 14: ‘ cried Frodo in amazement, springing to his feet, as if he expected the Ring to be demanded at once Chapter 16: With a suddenness that startled them all the wizard sprang to his feet Chapter 8: The hobbits sprang to their feet in alarm, and ran to the western rim Chapter 9: The local hobbits stared in amazement, and then sprang to their feet and shouted for Barliman |

|

take one’s advice |

Chapter 3: If I take your advice I may not see Gandalf for a long while, and I ought to know what is the danger that pursues me Chapter 11: When they saw them they were glad that they had taken his advice: the windows had been forced open and were swinging, and the curtains were flapping; the beds were tossed about, and the bolsters slashed and flung upon the floor; the brown mat was torn to pieces |

Таким образом, в большинстве случаев словоформы обрабатываются корректно.

Итоги

Учитывая вышеприведенный расчет со 120 словоформами, порожденными одной строкой словаря, поиск всех вхождений вместо первого, наличие регулярных выражений и громоздкость решения в целом, я не ожидала от программы быстрых результатов. Однако на ноутбуке с 4-ядерным Intel i5-8265U и 8 Гб ОЗУ словарь из 5 тыс. строк был проработан за 1.187 секунд. В итоге найдены 3.330 новых вхождений в дополнение к прежним 10.482, записанным вручную.

Вот так несколько десятков строк кода показали вполне удовлетворительные результаты для полнотекстового поиска с поддержкой морфологии английского языка. Программа работает достаточно корректно и быстро. Конечно, она не лишена недостатков – не застрахована от ложных срабатываний, не учтет флексию в середине многословного терма (например, takes his advice). Однако с поставленной задачей успешно справилась.