| Индийский океан | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Характеристики | |

| Площадь | 76,174 млн[1] км² |

| Объём | 282,65 млн[2] км³ |

| Наибольшая глубина | 7729 м |

| Средняя глубина | 3711 м |

| Расположение | |

| 14°05′34″ ю. ш. 76°18′38″ в. д.HGЯO | |

Инди́йский океа́н — третий по площади и глубине океан Земли, составляющий около 20 % её водной поверхности. Его площадь — 76,174 миллионов км², объём — 282,65 млн км³[2]. Самая глубокая точка океана находится в Зондском жёлобе (7729 метров[3][4]).

На севере омывает Азию, на западе — Африку, на востоке — Австралию; на юге граничит с Антарктидой. Граница с Атлантическим океаном проходит по 20° меридиану восточной долготы; с Тихим — по 146°55′ меридиану восточной долготы. Самая северная точка Индийского океана находится примерно на 30° северной широты в Персидском заливе. Ширина Индийского океана составляет приблизительно 10 000 км между южными точками Австралии и Африки. По площади он превосходит любой из континентов.

Этимология[править | править код]

Древние греки известную им западную часть океана с прилегающими морями и заливами называли Эритрейским морем (др.-греч. Ἐρυθρά θάλασσα — Красное, а в старых русских источниках — Чермное море). Постепенно это название стали относить только к ближайшему морю, а океан получает название по Индии, наиболее известной в то время своими богатствами стране на берегах океана. Так, Александр Македонский в IV веке до н. э. называет его Индикон пелагос (др.-греч. Ἰνδικόν πέλαγος) — «Индийское море». У арабов он известен как Бар-эль-Хинд (современное араб. المحيط الهندي — аль-му̣хӣ̣т аль-һиндий) — «Индийский океан». С XVI века утвердилось введённое римским учёным Плинием Старшим ещё в I веке название Океанус Индикус (лат. Oceanus Indicus) — Индийский океан[5].

Физико-географическая характеристика[править | править код]

| Океаны | Площадь поверхности воды, млн км² |

Объём, млн км³ |

Средняя глубина, м |

Наибольшая глубина океана, м |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Атлантический | 91,66 | 329,66 | 3597 | жёлоб Пуэрто-Рико (8742) |

| Индийский | 76,17 | 282,65 | 3711 | Зондский жёлоб (7729) |

| Северный Ледовитый | 14,75 | 18,07 | 1225 | Гренландское море (5527) |

| Тихий | 178,68 | 710,36 | 3976 | Марианская впадина (11022) |

| Мировой | 361,26 | 1340,74 | 3711 | 11 022 |

Общие сведения[править | править код]

Индийский океан главным образом расположен к югу от тропика Рака между Евразией на севере, Африкой на западе, Австралией на востоке и Антарктидой на юге[6]. Граница с Атлантическим океаном проходит по меридиану мыса Игольный (20° в. д. до побережья Антарктиды (Земля Королевы Мод)). Граница с Тихим океаном проходит: южнее Австралии — по восточной границе Бассова пролива до острова Тасмания, далее по меридиану 146°55′ в. д. до Антарктиды; севернее Австралии — между Андаманским морем и Малаккским проливом, далее по юго-западному берегу острова Суматра, Зондскому проливу, южному берегу острова Ява, южным границам морей Бали и Саву, северной границе Арафурского моря, юго-западным берегом Новой Гвинеи и западной границе Торресова пролива[7]. Иногда южную часть океана, с северной границей от 35° ю. ш. (по признаку циркуляции воды и атмосферы) до 60° ю. ш. (по характеру рельефа дна), относят к Южному океану.

Моря, заливы, острова[править | править код]

Площадь морей, заливов и проливов Индийского океана составляет 11,68 миллионов км² (15 % от общей площади океана), объём 26,84 миллионов км³ (9,5 %). Моря и основные заливы располагающиеся вдоль побережья океана (по часовой стрелке): Красное море, Аравийское море (Аденский залив, Оманский залив, Персидский залив), Лаккадивское море, Бенгальский залив, Андаманское море, Тиморское море, Арафурское море (залив Карпентария), Большой Австралийский залив, море Моусона, море Дейвиса, море Содружества, Море Космонавтов (последние четыре иногда относят к Южному океану)[2].

Некоторые острова — например, Мадагаскар, Сокотра, Мальдивские — являются фрагментами древних материков, другие — Андаманские, Никобарские или остров Рождества — имеют вулканическое происхождение. Крупнейший остров Индийского океана — Мадагаскар (590 тысяч км²). Крупнейшие острова и архипелаги: Тасмания, Шри-Ланка, архипелаг Кергелен, Андаманские острова, Мелвилл, Маскаренские острова (Реюньон, Маврикий), Кенгуру, Ниас, Ментавайские острова (Сиберут), Сокотра, Грут-Айленд, Коморские острова, острова Тиви (Батерст), Занзибар, Симёлуэ, острова Фюрно (Флиндерс), Никобарские острова, Кешм, Кинг, острова Бахрейн, Сейшельские острова, Мальдивские острова, архипелаг Чагос[2].

-

Остров Флиндерс

-

Вид на океан с побережья Танзании

-

Заход солнца на пляже в Австралии

-

Национальный парк Уджунг Кулон, Индонезия

История формирования океана[править | править код]

В раннеюрское время древний суперконтинент Гондвана начал раскалываться. В результате образовались Африка с Аравией, Индостан и Антарктида с Австралией.

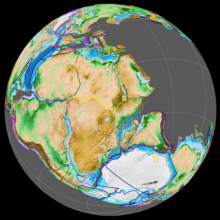

Индостан с Мадагаскаром 150 млн лет назад; первая океаническая кора между Мадагаскаром и Африкой

Процесс завершился на рубеже юрского и мелового периодов (140—130 миллионов лет назад), и начала образовываться молодая впадина современного Индийского океана.

Открытие западной части Индийского океана 70 млн лет назад: первая океаническая кора между Индией и Мадагаскаром

В меловой период дно океана разрасталось за счёт перемещения Индостана к северу и сокращения площади океанов Тихого и Тетиса. В позднемеловое время начался раскол единого Австрало-Антарктического материка. В это же время в результате образования новой рифтовой зоны Аравийская плита откололась от Африканской, и образовались Красное море и Аденский залив. В начале кайнозойской эры прекратилось разрастание Индийского океана в сторону Тихого, но продолжилось в сторону моря Тетис. В конце эоцена — начале олигоцена произошло столкновение Индостанской плиты с Азиатским континентом[8].

Сегодня движение тектонических плит продолжается. Осью этого движения являются срединно-океанические рифтовые зоны Африканско-Антарктического хребта, Центрально-Индийского хребта и Австрало-Антарктического поднятия. Австралийская плита продолжает движение на север со скоростью 5—7 см в год. В том же направлении со скоростью 3—6 см в год продолжает движение Индийская плита. Аравийская плита движется на северо-восток со скоростью 1—3 см в год. От Африканской плиты продолжает откалываться Сомалийская плита по Восточно-Африканской рифтовой зоне, которая движется со скоростью 1—2 см в год в северо-восточном направлении[9]. 26 декабря 2004 года в Индийском океане у острова Симёлуэ, расположенного возле северо-западного берега острова Суматры (Индонезия), произошло самое крупное за всю историю наблюдений землетрясение магнитудой до 9,3. Причиной послужил сдвиг около 1200 км (по некоторым оценкам — 1600 км) земной коры на расстояние в 15 м вдоль зоны субдукции, в результате чего Индостанская плита сдвинулась под Бирманскую плиту. Землетрясение вызвало цунами, принёсшее громадные разрушения и огромное количество погибших (до 300 тысяч человек)[10].

Геологическое строение и рельеф дна[править | править код]

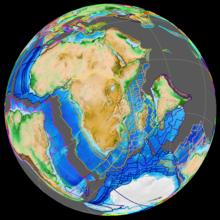

Карта глубин Индийского океана

Срединно-океанические хребты[править | править код]

Срединно-океанические хребты делят дно Индийского океана на три сектора: Африканский, Индо-Австралийский и Антарктический. Выделяются пять срединно-океанических хребтов: Западно-Индийский, Аравийско-Индийский, Центральноиндийский, Восточно-Индийский хребты и Австрало-Антарктическое поднятие. Западно-Индийский хребет расположен в юго-западной части океана. Для него характерны подводный вулканизм, сейсмичность, кора рифтогенального типа и рифтовая структура осевой зоны, его секут несколько океанических разломов субмеридионального простирания. В районе острова Родригес (Маскаренский архипелаг) существует так называемое тройное соединение, где система хребтов разделяется к северу на Аравийско-Индийский хребет и к юго-западу на Центральноиндийский хребет. Аравийско-Индийский хребет сложен из ультраосновных пород, выявлен ряд секущих разломов субмеридионального простирания, с которыми связаны очень глубокие впадины (океанические троги) с глубинами до 6,4 км. Северную часть хребта пересекает самый мощный разлом Оуэн, по которому северный отрезок хребта испытал смещение на 250 км к северу. Далее на запад рифтовая зона продолжается в Аденском заливе и на северо-северо-западе в Красном море. Здесь рифтовая зона сложена карбонатными отложениями с вулканическими пеплами. В рифтовой зоне Красного моря обнаружены толщи эвапоритов и металлоносных илов, связанные с мощными горячими (до 70 °C) и очень солёными (до 350 ‰) ювенильными водами[6].

В юго-западном направлении от тройного соединения простирается Центральноиндийский хребет, имеющий хорошо выраженную рифтовую и фланговые зоны, заканчивающийся на юге вулканическим плато Амстердам с вулканическими островами Сен-Поль и Амстердам. От этого плато на востоко-юго-восток простирается Австрало-Антарктическое поднятие, имеющее вид широкого, слаборасчленённого свода. В восточной части поднятие расчленено серией меридиональных разломов на ряд сегментов, смещённых относительно друг друга в меридиональном направлении[6].

Африканский сегмент океана[править | править код]

Подводная окраина Африки имеет узкий шельф и чётко выраженный материковый склон с окраинными плато и материковым подножием. На юге Африканский континент образует выдвинутые на юг выступы: банку Агульяс, Мозамбикский и Мадагаскарский хребты, сложенные земной корой материкового типа. Материковое подножие образует расширяющийся к югу вдоль побережья Сомали и Кении наклонную равнину, которая продолжается в Мозамбикском проливе и окаймляет Мадагаскар с востока. По востоку сектора проходит Маскаренский хребет, в северной части которого находятся Сейшельские острова[6].

Поверхность ложа океана в секторе, особенно вдоль срединно-океанических хребтов, расчленена многочисленными грядами и ложбинами, связанными с зонами разломов субмеридионального направления. Встречается много подводных вулканических гор, большинство из которых надстроено коралловыми надстройками в виде атоллов и подводных коралловых рифов. Между горными поднятиями находятся котловины ложа океана с холмистым и горным рельефом: Агульяс, Мозамбикская, Мадагаскарская, Маскаренская и Сомалийская. В Сомалийской и Маскаренской котловинах сформированы обширные плоские абиссальные равнины, куда поступает значительный объём терригенного и биогенного осадочного материала. В Мозамбикской котловине располагается подводная долина реки Замбези с системой конусов выноса[6].

Индо-Австралийский сегмент океана[править | править код]

Индо-Австралийский сегмент занимает половину площади Индийского океана. На западе в меридиональном направлении проходит Мальдивский хребет, на вершинной поверхности которого расположены острова Лаккадивские, Мальдивские и Чагос. Хребет сложен корой континентального типа. Вдоль побережья Аравии и Индостана протянулись очень узкий шельф, узкий и крутой материковый склон и очень широкое материковое подножие, в основном образованное двумя гигантскими конусами выноса мутьевых потоков рек Инд и Ганг. Эти две реки выносят в океан по 400 миллионов тонн обломочного материала. Индский конус далеко выдвинут в пределы Аравийской котловины. И только южная часть этой котловины занята плоской абиссальной равниной с отдельными подводными горами[6][11].

Почти точно по 90° в. д. на 4000 км с севера на юг протягивается глыбовый океанический Восточно-Индийский хребет. Между Мальдивским и Восточно-Индийским хребтами расположена Центральная котловина — самая крупная котловина Индийского океана. Её северную часть занимает Бенгальский конус выноса (от реки Ганг), к южной границе которого примыкает абиссальная равнина. В центральной части котловины расположен небольшой хребет Ланка и подводная гора Афанасия Никитина[12][13]. К востоку от Восточно-Индийского хребта располагаются Кокосовая и Западно-Австралийская котловины, разделённые глыбовым субширотно ориентированным Кокосовым поднятием с островами Кокосовыми и Рождества. В северной части Кокосовой котловины имеется плоская абиссальная равнина. С юга она ограничена Западно-Австралийским поднятием, круто обрывающимся к югу и полого погружающимся под дно котловины к северу. С юга Западно-Австралийское поднятие ограничено крутым уступом, связанным с зоной разломов Диамантина. В зоне разломов сочетаются глубокие и узкие грабены (наиболее значительные — Обь и Диаматина) и многочисленные узкие горсты[6].

Переходная область Индийского океана представлена Андаманским жёлобом и глубоководным Зондским жёлобом, к которому приурочена максимальная глубина Индийского океана (7209 м). Внешним хребтом Зондской островной дуги являются подводный Ментавайский хребет и его продолжение в виде Андаманских и Никобарских островов[6].

Подводная окраина Австралийского материка[править | править код]

Северная часть австралийского континента окаймлена широким Сахульским шельфом со множеством коралловых построек. К югу этот шельф сужается и вновь расширяется у побережья южной Австралии. Материковый склон сложен краевыми плато (наиболее крупные из них — плато Эксмут и Натуралистов). В западной части Западно-Австралийской котловины располагаются поднятия Зенит, Кювье и другие, которые являются кусками континентальной структуры. Между южной подводной окраиной Австралии и Австрало-Антарктическим поднятием расположена небольшая Южно-Австралийская котловина, представляющая собой плоскую абиссальную равнину[6].

Антарктический сегмент океана[править | править код]

Антарктический сегмент ограничен Западно-Индийским и Центральноиндийским хребтами, а с юга — берегами Антарктиды. Под воздействием тектонических и гляциологических факторов шельф Антарктиды переуглублён. Широкий материковый склон прорезают крупные и широкие каньоны, по которым осуществляется сток переохлаждённых вод с шельфа в абиссальные впадины. Материковое подножие Антарктиды отличается широкой и значительной (до 1,5 км) мощностью рыхлых отложений[6].

Крупнейший выступ Антарктического материка — Кергеленское плато, а также вулканическое поднятие островов Принс-Эдуард и Крозе, которые делят Антарктический сектор на три котловины. На западе располагается Африканско-Антарктическая котловина, которая наполовину располагается в Атлантическом океане. Большая часть её дна — плоская абиссальная равнина. Расположенная севернее котловина Крозе отличается крупнохолмистым рельефом дна. Австрало-Антарктическая котловина, лежащая к востоку от Кергелена, в южной части занята плоской равниной, а в северной — абиссальными холмами[6].

Донные отложения[править | править код]

В Индийском океане преобладают известковые фораминиферово-кокколитовые отложения, занимающие более половины площади дна. Широкое развитие биогенных (в том числе коралловых) известковых отложений объясняется положением большой части Индийского океана в пределах тропических и экваториальных поясов, а также относительно небольшой глубиной океанических котловин. Многочисленные горные поднятия также благоприятны для образования известковых осадков. В глубоководных частях некоторых котловин (например, Центральной, Западно-Австралийской) залегают глубоководные красные глины. В экваториальном поясе характерны радиоляриевые илы. В южной холодной части океана, где условия для развития диатомовой флоры особенно благоприятны, представлены кремнистые диатомовые отложения. У антарктического берега отлагаются айсберговые осадки. На дне Индийского океана значительное распространение получили железомарганцевые конкреции, приуроченные главным образом к областям отложения красных глин и радиоляриевых илов[6].

Климат[править | править код]

В данном регионе выделяются четыре климатических пояса, вытянутые вдоль параллелей. Под влиянием Азиатского континента в северной части Индийского океана устанавливается муссонный климат с частыми циклонами, перемещающимися в направлении побережий. Высокое атмосферное давление над Азией зимой вызывает образование северо-восточного муссона. Летом он сменяется влажным юго-западным муссоном, несущим воздух из южных районов океана. Во время летнего муссона часто бывает ветер силой более 7 баллов (с повторяемостью 40 %). Летом температура над океаном составляет 28—32 °C, зимой понижается до 18—22 °C[14].

В южных тропиках господствует юго-восточный пассат, который в зимнее время не распространяется севернее 10 °с. ш. Средняя годовая температура достигает 25 °C. В зоне 40—45°ю. ш. В течение всего года характерен западный перенос воздушных масс, особенно силён в умеренных широтах, где повторяемость штормовой погоды составляет 30—40 %. В средней части океана штормовая погода связана с тропическими ураганами. Зимой они могут возникать и в южной тропической зоне. Чаще всего ураганы возникают в западной части океана (до 8 раз в год), в районах Мадагаскара и Маскаренских островов. В субтропических и умеренных широтах летом температура достигает 10—22 °C, а зимой — 6—17 °C. От 45 градусов и южнее характерны сильные ветры. Зимой температура здесь колеблется от −16 °C до 6 °C, а летом — от −4 °C до 10 °C[14].

Максимальное количество осадков (2,5 тысячи мм) приурочено к восточной области экваториальной зоны. Здесь же отмечается повышенная облачность (более 5 баллов). Наименьшее количество осадков наблюдается в тропических районах южного полушария, особенно в восточной части. В северном полушарии большую часть года ясная погода характерна для Аравийского моря. Максимум облачности наблюдается в антарктических водах[14].

Циркуляция поверхностных вод[править | править код]

В северной части океана наблюдается сезонная смена течений, вызванная муссонной циркуляцией. Зимой устанавливается Северо-восточное муссонное течение, начинающееся в Бенгальском заливе. Южнее 10° с. ш. это течение переходит в Западное течение, пересекающее океан от Никобарских островов до берегов Восточной Африки. Далее оно разветвляется: одна ветвь идёт на север в Красное море, другая — на юг до 10° ю. ш. и, повернув на восток, даёт начало Экваториальному противотечению. Последнее пересекает океан и у берегов Суматры вновь разделяется на часть, уходящую в Андаманское море и основную ветвь, которая между Малыми Зондскими островами и Австралией направляется в Тихий океан. Летом юго-западный муссон обеспечивает перемещение всей массы поверхностных вод на восток, и Экваториальное противотечение исчезает. Летнее муссонное течение начинается у берегов Африки мощным Сомалийским течением, к которому в районе Аденского залива присоединяется течение из Красного моря. В Бенгальском заливе летнее муссонное течение разделяется на северное и южное, которое вливается в Южное Пассатное течение[14].

В южном полушарии течения носят постоянный характер, без сезонных колебаний. Возбуждаемое пассатами Южное Пассатное течение пересекает океан с востока на запад к Мадагаскару. Оно усиливается в зимнее (для южного полушария) время, за счёт дополнительного питания водами Тихого океана, поступающих вдоль северного берега Австралии. У Мадагаскара Южное Пассатное течение разветвляется, давая начало Экваториальному противотечению, Мозамбикскому и Мадагаскарскому течениям. Сливаясь юго-западнее Мадагаскара, они образуют тёплое течение Агульяс. Южная часть этого течения уходит в Атлантический океан, а часть вливается в течение Западных ветров. На подходе к Австралии от последнего отходит на север холодное Западно-Австралийское течение. В Аравийском море, Бенгальском и Большом Австралийском заливах и в приантарктических водах действуют местные круговороты[14].

Для северной части Индийского океана характерно преобладание полусуточного прилива. Амплитуды прилива в открытом океане невелики и в среднем составляют 1 м. В антарктической и субантарктической зонах амплитуда приливов уменьшается с востока на запад от 1,6 м до 0,5 м, а вблизи берегов возрастают до 2—4 м. Максимальные амплитуды отмечаются между островами, в мелководных заливах. В Бенгальском заливе величина прилива 4,2—5,2 м, вблизи Мумбаи — 5,7 м, у Янгона — 7 м, у северо-западной Австралии — 6 м, а в порту Дарвин — 8 м. В остальных районах амплитуда приливов порядка 1—3 м[11].

| Приход | Количество воды в тыс. км³ в год |

Расход | Количество воды в тыс. км³ в год |

|---|---|---|---|

| Из Атлантического океана через разрез Африка — Антарктида (20° в. д.) с течением Западных Ветров (Антарктическим циркумполярным течением) | 4976 | В Атлантический океан через разрез Африка — Антарктида (20° в. д.) с Прибрежным антарктическим течением, глубинными и придонными водами | 1692 |

| Из Тихого океана через проливы индонезийских морей | 67 | В Тихий океан через разрез Австралия — Антарктида (147° в. д.) с течением Западных Ветров (Антарктическим циркумполярным течением) | 5370 |

| Из Тихого океана через разрез Австралия — Антарктида (147° в. д.) с Прибрежным антарктическим течением, глубинными и придонными водами | 2019 | Испарение | 108 |

| Осадки | 100 | ||

| Речной сток | 6 | ||

| Подземный сток | 1 | ||

| Поступление от таяния антарктических льдов | 1 | ||

| Всего | 7170 | Всего | 7170 |

Температура, солёность воды[править | править код]

В экваториальной зоне Индийского океана круглый год температура поверхностных вод около 28 °C как в западной, так и восточной частях океана. В Красном и Аравийском морях зимняя температура снижается до 20—25 °C, но летом в Красном море устанавливаются максимальные температуры для всего Индийского океана — до 30—31 °C. Высокие зимние температуры воды (до 29 °C) характерны для берегов северо-западной Австралии. В южном полушарии в тех же широтах в восточной части океана температура воды зимой и летом на 1—2° ниже, чем в западной. Температура воды ниже 0 °C в летнее время отмечается к югу от 60° ю. ш. Лёдообразование в этих районах начинается в апреле и толщина припая к концу зимы достигает 1—1,5 м. Таяние начинается в декабре—январе, и к марту происходит полное очищение вод от припайных льдов. В южной части Индийского океана распространены айсберги, заходящие иногда севернее 40° ю. ш.[14]

Максимальная солёность поверхностных вод наблюдается в Персидском заливе и Красном море, где она достигает 40—41 ‰. Высокая солёность (более 36 ‰) также наблюдается в южном тропическом поясе, особенно в восточных районах, а в северном полушарии также в Аравийском море. В соседнем Бенгальском заливе за счёт опресняющего влияния стока Ганга с Брахмапутрой и Иравади солёность снижается до 30—34 ‰. Повышенная солёность соотносится с зонами максимального испарения и наименьшего количества атмосферных осадков. Пониженная солёность (менее 34 ‰) характерна для приантарктических вод, где сказывается сильное опресняющее действие талых ледниковых вод. Сезонное различие солёности значительно только в антарктической и экваториальной зонах. Зимой опреснённые воды из северо-восточной части океана переносятся муссонным течением, образуя язык пониженной солёности вдоль 5° с. ш. Летом этот язык исчезает. В арктических водах в зимнее время солёность несколько повышается за счёт осолонения вод в процессе льдообразования. От поверхности ко дну океана солёность убывает. Придонные воды от экватора до арктических широт имеют солёность 34,7—34,8 ‰[14].

Водные массы[править | править код]

Воды Индийского океана разделяются на несколько водных масс. В части океана севернее 40° ю. ш. выделяют центральную и экваториальную поверхностные и подповерхностные водные массы и подстилающую их (глубже 1000 м) глубинную. На север до 15—20° ю. ш. распространяется центральная водная масса. Температура меняется с глубиной от 20—25 °C до 7—8 °C, солёность 34,6—35,5 ‰. Поверхностные слои севернее 10—15° ю. ш. составляют экваториальную водную массу с температурой 4—18 °C и солёностью 34,9—35,3 ‰. Эта водная масса отличается значительными скоростями горизонтального и вертикального перемещения. В южной части океана выделяются субантарктическая (температура 5—15 °C, солёность до 34 ‰) и антарктическая (температура от 0 до −1 °C, солёность из-за таяния льдов понижается до 32 ‰). Глубинные водные массы разделяют на: очень холодные циркуляционные, образующиеся путём опускания арктических водных масс и притока циркуляционных вод из Атлантического океана; южноиндийские, формирующиеся в результате опускания субарктических поверхностных вод; североиндийские, образующиеся плотными водами, вытекающими из Красного моря и Оманского залива. Глубже 3,5—4 тысяч м распространены донные водные массы, формирующиеся из антарктических переохлаждённых и плотных солёных вод Красного моря и Персидского залива[14].

Феномен неравномерного нагрева воды в западной и восточной части океана, впервые описанный в 1999 году, именуется Индоокеанским диполем. Наряду с Эль-Ниньо это один из основных факторов, определяющих климат Австралии.

Флора и фауна[править | править код]

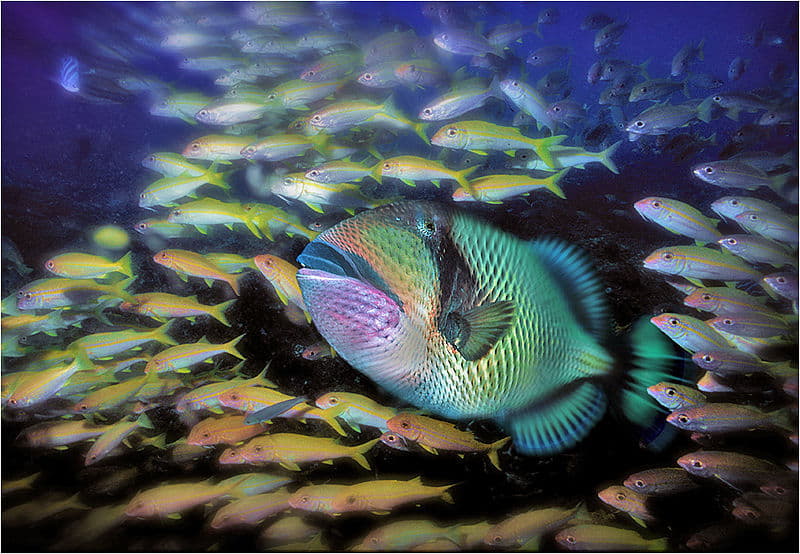

Флора и фауна Индийского океана необычайно разнообразны. Тропическая область выделяется богатством планктона. Особенно обильна одноклеточная водоросль триходесмиум (цианобактерии), из-за которой поверхностный слой воды сильно мутнеет и меняет свою окраску. Планктон Индийского океана отличает большое число светящихся ночью организмов: перидиней, некоторых видов медуз, гребневиков, оболочников. Обильно встречаются ярко окрашенные сифонофоры, в том числе ядовитые физалии. В умеренных и арктических водах главными представителями планктона являются копеподы, эуфаузиды и диатомеи. Наиболее многочисленными рыбами Индийского океана являются корифены, тунцы, нототениевые и разнообразные акулы. Из пресмыкающихся имеются несколько видов гигантских морских черепах, морские змеи, из млекопитающих — китообразные (беззубые и синие киты, кашалоты, дельфины), тюлени, морские слоны. Большинство китообразных обитают в умеренных и приполярных областях, где благодаря интенсивному перемешиванию вод возникают благоприятные условия для развития планктонных организмов[14]. Птицы представлены альбатросами и фрегатами, а также несколькими видами пингвинов, населяющими побережья Южной Африки, Антарктиды и острова, лежащие в умеренном поясе океана[15].

Растительный мир Индийского океана представлен бурыми (саргассовые, турбинарии) и зелёными водорослями (каулерпа). Пышно развиваются также известковые водоросли литотамния и халимеда, которые участвуют вместе с кораллами в сооружении рифовых построек. В процессе деятельности рифообразующих организмов создаются коралловые платформы, достигающие иногда ширины в несколько километров. Типичным для прибрежной зоны Индийского океана является фитоценоз, образуемый мангровыми зарослями. Особенно такие заросли характерны для устьев рек и занимают значительные площади в Юго-Восточной Африке, на западном Мадагаскаре, в Юго-Восточной Азии и других районах. Для умеренных и приантарктических вод наиболее характерны красные и бурые водоросли, главным образом из групп фукусовых и ламинариевых, порфира, гелидиум. В приполярных областях южного полушария встречаются гигантские макроцистисы[11][14].

Зообентос представлен разнообразными моллюсками, известковыми и кремнёвыми губками, иглокожими (морские ежи, морские звёзды, офиуры, голотурии), многочисленными ракообразными, гидроидами, мшанками. В тропической зоне широко распространены коралловые полипы[14].

-

Мангровые заросли на юге Индии

-

-

-

Экологические проблемы[править | править код]

Хозяйственная деятельность человека в Индийском океане привела к загрязнению его вод и к сокращению биоразнообразия. В начале XX века некоторые виды китов оказались почти полностью истреблёнными, другие — кашалоты и сейвалы — ещё сохранились, но их количество сильно сократилось[14]. С сезона 1985—1986 годов Международной комиссией по промыслу китов был введён полный мораторий на коммерческий китобойный промысел любых видов. В июне 2010 года на 62-м заседании Международной Китобойной Комиссии под давлением Японии, Исландии и Дании мораторий не был продлён[16]. Символом вымирания и исчезновения видов стал Маврикийский дронт, уничтоженный к 1651 году на острове Маврикий. После того как он вымер, у людей впервые сформировалось мнение, что они могут вызвать вымирание и других животных[17].

Большую опасность в океане представляет загрязнение вод нефтью и нефтепродуктами (основными загрязнителями), некоторыми тяжёлыми металлами и отходами атомной промышленности. Через океан пролегают маршруты нефтетанкеров, транспортирующих нефть из стран Персидского залива. Любая крупная авария может привести к экологической катастрофе и гибели множества животных, птиц и растений[18].

Государства Индийского океана[править | править код]

Государства вдоль границ Индийского океана (по часовой стрелке): Южно-Африканская Республика, Мозамбик, Танзания, Кения, Сомали, Джибути, Эритрея, Судан, Египет, Израиль, Иордания, Саудовская Аравия, Йемен, Оман, Объединённые Арабские Эмираты, Катар, Кувейт, Ирак, Иран, Пакистан, Индия, Бангладеш, Мьянма, Таиланд, Малайзия, Индонезия, Восточный Тимор, Австралия. В Индийском океане расположены островные государства и владения государств, не входящих в регион: Бахрейн, Британская территория в Индийском океане (Великобритания), Коморские Острова, Маврикий, Мадагаскар, Майотта (Франция), Мальдивы, Реюньон (Франция), Сейшельские Острова, Французские Южные и Антарктические территории (Франция), Шри-Ланка.

История исследования[править | править код]

Карта Индийского океана. 1658 год

Берега Индийского океана — один из районов расселения древнейших народов и возникновения первых речных цивилизаций. В глубокой древности суда типа джонок и катамаранов использовались людьми для плавания под парусом, при попутных муссонах из Индии в Восточную Африку и обратно. Египтяне за 3500 лет до нашей эры вели оживлённую морскую торговлю со странами Аравийского полуострова, Индией и Восточной Африкой. Страны Месопотамии за 3000 лет до нашей эры совершали морские походы в Аравию и Индию. С VI века до нашей эры финикийцы, по свидетельству греческого историка Геродота, совершали морские походы из Красного моря по Индийскому океану в Индию и вокруг Африки. В VI—V веках до нашей эры персидские купцы вели морскую торговлю от устья реки Инд вдоль восточного побережья Африки. По окончании индийского похода Александра Македонского в 325 году до нашей эры греки огромным флотом с пятитысячной командой в тяжёлых штормовых условиях совершили многомесячное плавание между устьями рек Инда и Евфрата. Византийские купцы в IV—VI веках проникали на востоке в Индию, а на юге — в Эфиопию и Аравию[19]. Начиная с VII века арабские мореходы начали интенсивное исследование Индийского океана. Они отлично изучили побережье Восточной Африки, Западной и Восточной Индии, островов Сокотра, Ява и Цейлон, посещали Лаккадивские и Мальдивские острова, острова Сулавеси, Тимор и другие[20].

В конце XIII века венецианский путешественник Марко Поло на обратном пути из Китая прошёл через Индийский океан от Малаккского до Ормузского пролива, посетив Суматру, Индию, Цейлон. Путешествие было описано в «Книге о разнообразии мира», которая оказала значительное влияние на мореплавателей, картографов, писателей Средневековья в Европе[21]. Китайские джонки совершали походы вдоль азиатских берегов Индийского океана и достигали Восточных берегов Африки (например, семь путешествий Чжэн Хэ в 1405—1433 годах). Экспедиция под управлением португальского мореплавателя Васко да Гама, обогнув Африку с юга, пройдя вдоль восточного берега континента в 1498 году, достигла Индии. В 1642 году голландская торговая Ост-Индская компания организовала экспедицию из двух кораблей под командованием капитана Тасмана. В результате этой экспедиции была исследована центральная часть Индийского океана и было доказано, что Австралия — материк. В 1772 году британская экспедиция под командованием Джеймса Кука проникла на юг Индийского океана до 71° ю. ш., при этом был получен обширный научный материал по гидрометеорологии и океанографии[19].

С 1872 по 1876 годы проходила первая научная океаническая экспедиция на английском парусно-паровом корвете «Челленджер»[22], были получены новые данные о составе вод океана, о растительном и животном мирах, о рельефе дна и грунтах, составлена первая карта глубин океана и собрана первая коллекция глубоководных животных. Кругосветная экспедиция на российском парусно-винтовом корвете «Витязь» 1886—1889 годов под руководством учёного-океанографа С. О. Макарова провела масштабную исследовательскую работу в Индийском океане[23]. Большой вклад в исследование Индийского океана внесли океанографические экспедиции на немецких судах «Валькирия» (1898—1899) и «Гаусс» (1901—1903), на английском судне «Дисковери II» (1930—1951), советском экспедиционном судне «Обь» (1956—1958) и другие. В 1960—1965 под эгидой Межправительственной океанографической экспедицией при ЮНЕСКО была проведена международная Индоокеанская экспедиция. Она была самой крупной из всех экспедиций, когда-либо работавших в Индийском океане. Программа океанографических работ охватывала наблюдениями почти весь океан, чему способствовало участие в исследованиях учёных около 20 стран. В их числе: советские и зарубежные учёные на исследовательских судах «Витязь», «А. И. Воейков», «Ю. М. Шокальский», немагнитной шхуне «Заря» (СССР), «Наталь» (ЮАР), «Диамантина» (Австралия), «Кистна» и «Варуна» (Индия), «Зулфиквар» (Пакистан). В результате были собраны новые ценные данные по гидрологии, гидрохимии, метеорологии, геологии, геофизике и биологии Индийского океана[24]. С 1972 года на американском судне «Гломар Челленджер» проводились регулярные глубоководные бурения, работы по изучению перемещения водных масс на больших глубинах, биологические исследования[25].

В последние десятилетия проводились многочисленные измерения океана с помощью космических спутников. Результатом явился выпущенный в 1994 году Американским Национальным Центром геофизических данных батиметрический атлас океанов с разрешением карт 3—4 км и точностью глубины ±100 м[26].

В 2014 году в южной части Индийского океана проводились масштабные поисковые работы в связи с катастрофой пассажирского самолёта Боинг-777 авиакомпании Malaysia Airlines. В районах поисков было проведено подробное картографирование морского дна, в результате чего были открыты новые подводные горы, хребты и вулканы[27][28][29].

Экономическое и хозяйственное значение[править | править код]

Рыболовство и морские промыслы[править | править код]

Значение Индийского океана для мирового рыболовного промысла невелико: уловы здесь составляют лишь 5 % от общего объёма. Главные промысловые рыбы здешних вод — тунец, сардина, камса, несколько видов акул, барракуды и скаты; ловят здесь также креветок, омаров и лангустов[15]. Ещё недавно интенсивный в южных районах океана китобойный промысел быстро свёртывается, из-за почти полного истребления некоторых видов китов[14]. На северо-западном берегу Австралии, в Шри-Ланка и на Бахрейнских островах добываются жемчуг и перламутр[15].

Транспортные пути[править | править код]

Важнейшими транспортными путями Индийского океана являются маршруты из Персидского залива в Европу, Северную Америку, Японию и Китай, а также из Аденского залива в Индию, Индонезию, Австралию, Японию и Китай. Основные судоходные проливы Индийского пролива: Мозамбикский, Баб-эль-Мандебский, Ормузский, Зондский. Индийский океан соединяется искусственным Суэцким каналом со Средиземным морем Атлантического океана. В Суэцком канале и Красном море сходятся и расходятся все главнейшие грузопотоки Индийского океана. Крупные порты: Дурбан, Мапуту (вывоз: руда, уголь, хлопок, минеральное сырьё, нефть, асбест, чай, сахар-сырец, орехи кешью, ввоз: машины и оборудование, промышленные товары, продовольствие), Дар-эс-Салам (вывоз: хлопок, кофе, сизаль, алмазы, золото, нефтепродукты, орех кешью, гвоздика, чай, мясо, кожа, ввоз: промышленные товары, продовольствие, химикаты), Джидда, Салала, Дубай, Бендер-Аббас, Басра (вывоз: нефть, зерно, соль, финики, хлопок, кожа, ввоз: машины, лес, текстиль, сахар, чай), Карачи (вывоз: хлопок, ткани, шерсть, кожа, обувь, ковры, рис, рыба, ввоз: уголь, кокс, нефтепродукты, минеральные удобрения, оборудование, металлы, зерно, продовольствие, бумага, джут, чай, сахар), Мумбаи (вывоз: марганцевая и железная руды, нефтепродукты, сахар, шерсть, кожа, хлопок, ткани, ввоз: нефть, уголь, чугун, оборудование, зерно, химикалии, промышленные товары), Коломбо, Ченнаи (железная руда, уголь, гранит, удобрения, нефтепродукты, контейнеры, автомобили), Калькутта (вывоз: уголь, железная и медная руды, чай, ввоз: промышленные товары, зерно, продовольствие, оборудование), Читтагонг (одежда, джут, кожа, чай, химические вещества), Янгон (вывоз: рис, твёрдая древесина, цветные металлы, жмых, бобовые, каучук, драгоценные камни, ввоз: уголь, машины, продовольствие, ткани), Перт-Фримантл (вывоз: руды, глинозём, уголь, кокс, каустическая сода, фосфорное сырьё, ввоз: нефть, оборудование)[30][31].

-

Порт Мумбаи, Индия

-

Яхта султана Омана, порт Маскат (Оман)

-

Суэцкий канал

-

Сейшельский международный аэропорт

Полезные ископаемые[править | править код]

Важнейшими полезными ископаемыми Индийского океана являются нефть и природный газ. Их месторождения имеются на шельфах Персидского и Суэцкого заливов, в проливе Басса, на шельфе полуострова Индостан. На побережьях Индии, Мозамбика, Танзании, ЮАР, островов Мадагаскар и Шри-Ланка эксплуатируются ильменит, монацит, рутил, титанит и цирконий. У берегов Индии и Австралии имеются залежи барита и фосфорита, а в шельфовых зонах Индонезии, Таиланда и Малайзии в промышленных масштабах эксплуатируются месторождения касситерита и ильменита[11].

Рекреационные ресурсы[править | править код]

Основные рекреационные зоны Индийского океана: Красное море, западное побережье Таиланда, острова Малайзии и Индонезии, остров Шри-Ланка, район прибрежных городских агломераций Индии, восточное побережье острова Мадагаскар, Сейшельские и Мальдивские острова[32]. Среди стран Индийского океана с наибольшим потоком туристов (по данным на 2010 год Всемирной туристской организации) выделяются: Малайзия (25 миллионов посещений в год), Таиланд (16 миллионов), Египет (14 миллионов), Саудовская Аравия (11 миллионов), Южная Африка (8 миллионов), Арабские Эмираты (7 миллионов), Индонезия (7 миллионов), Австралия (6 миллионов), Индия (6 миллионов), Катар (1,6 миллиона), Оман (1,5 миллиона)[33].

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Географический атлас. — М.: ГУГК, 1982. — С. 206. — 238 с. — 227 000 экз.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Атлас океанов. Термины, понятия, справочные таблицы. — М.: ГУНК МО СССР, 1980. — С. 84—119.

- ↑ Зондский жёлоб // География. Современная иллюстрированная энциклопедия / Главный редактор А. П. Горкин. — М.: Росмэн-Пресс, 2006. — 624 с. — ISBN 5-353-02443-5.

- ↑ Индийский океан // Казахстан. Национальная энциклопедия. — Алматы: Қазақ энциклопедиясы, 2005. — Т. II. — ISBN 9965-9746-3-2. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- ↑ Поспелов Е. М. Географические названия мира: Топонимический словарь. — 2-е изд., стереотип. — М.: Русские словари, Астрель, АСТ, 2001. — С. 75—76.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Физическая география материков и океанов / Под общей ред. А. М. Рябчикова. — М.: Высшая школа, 1988. — С. 527—530.

- ↑ Индийский океан / Деев М. Г., Турко Н. Н. и др. // Большая российская энциклопедия [Электронный ресурс]. — 2016.

- ↑ Ушаков С. А., Ясаманов Н. А. Дрейф материков и климаты Земли. — М.: Мысль, 1984. — С. 142—191.

- ↑ Ушаков С. А., Ясаманов Н. А. Дрейф материков и климаты Земли. — М.: Мысль, 1984. — С. 10—15.

- ↑ Землетрясение в Индийском океане в 2004 году. Данные цунами. Цунами.ком. Дата обращения: 20 июня 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2012 года.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Каплин П. А., Леонтьев О. К., Лукьянова С. А., Никифоров Л. Г. Берега. — М.: Мысль, 1991. — С. 284—295.

- ↑ Безруков П. Л., Затонский Л. К., Сергеев И. В. Гора Афанасия Никитина в Индийском океане // Доклады Академии наук СССР. — 1961. — Т. 139, № 1. — С. 199—202. Эта статья была включена в сборник ЮНЕСКО: International Indian Ocean Expedition. Collected reprints I (англ.). — Bruges: UNESCO, 1965. — P. 561—564. Архивировано 24 ноября 2018 года.

- ↑ Гора Афанасия Никитина обозначена на карте Индийского океана, например, в следующем издании: Атлас мира / Отв. ред. С. И. Сергеева. — М.: ГУГК СССР, 1988. — С. 202. — 337 с. — 40 000 экз.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Физическая география материков и океанов / Под общей ред. А. М. Рябчикова. — М.: Высшая школа, 1988. — С. 530—535.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Индийский океан // Ива — Италики. — М. : Советская энциклопедия, 1972. — (Большая советская энциклопедия : [в 30 т.] / гл. ред. А. М. Прохоров ; 1969—1978, т. 10).

- ↑ Япония, Исландия и Дания продолжат убивать китов. BuenoLatina. Дата обращения: 18 мая 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2011 года.

- ↑ Дронт. 4ygeca.com. Дата обращения: 18 июня 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2011 года.

- ↑ Индийский океан, Между Индией и Антарктикой. Web Design. Дата обращения: 14 июня 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 15 ноября 2012 года.

- ↑ 1 2 Серебряков В. В. География морских путей. — М.: Транспорт, 1981. — С. 7—30.

- ↑ Освоение арабскими мореходами Индийского океана. Мир океана. Дата обращения: 6 июня 2012. Архивировано 7 сентября 2011 года.

- ↑ Путешествия Марко Поло. Институт географии РАН. Дата обращения: 20 июня 2012. Архивировано 11 марта 2012 года.

- ↑ Челленджер. Океанология. Океанография – изучение, проблемы и ресурсы мирового океана. Дата обращения: 8 февраля 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 11 октября 2012 года.

- ↑ Исследования Мирового океана в 19 в. Океанология. Океанография – изучение, проблемы и ресурсы мирового океана. Дата обращения: 8 февраля 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2015 года.

- ↑ Работы в Индийском океане. GeoMan.ru: Библиотека по географии. Дата обращения: 14 июня 2012. Архивировано 2 ноября 2012 года.

- ↑ «Гломар Челленджер» и проект глубоководного бурения. Мир океана. Дата обращения: 8 февраля 2012. Архивировано 7 сентября 2011 года.

- ↑ 3.5 Батиметрические карты и базы данных. Океанология. Океанография – изучение, проблемы и ресурсы мирового океана. Дата обращения: 8 февраля 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2014 года.

- ↑ Газета. Ру — «Альпы выглядели бы как предгорья». В поисках малайзийского Boeing 777 учёные нашли подводные вулканы и высокие хребты. www.gazeta.ru. Дата обращения: 19 августа 2020. Архивировано 21 февраля 2018 года.

- ↑ BBC News: MH370 search faces tough next phase (англ.). www.bbc.com. Дата обращения: 19 августа 2020. Архивировано 11 ноября 2020 года.

- ↑ Карты дна океана в районах поисков (англ.). www.jacc.gov.au. Дата обращения: 19 августа 2020. Архивировано 17 октября 2018 года.

- ↑ Серебряков В. В. География морских путей. — М.: Транспорт, 1981. — С. 69—187.

- ↑ WORLD PORT RANKING – 2008 (англ.). Дата обращения: 23 июля 2012. Архивировано 2 декабря 2012 года.

- ↑ Рекреационные ресурсы. Страны и континенты. Дата обращения: 18 мая 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2013 года.

- ↑ UNWTO World Tourism Barometer. 2011 edition (англ.). Всемирная туристская организация ЮНВТО. Дата обращения: 18 мая 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2012 года.

Литература[править | править код]

- Атлас океанов. Термины, понятия, справочные таблицы. — М.: ГУНК МО СССР, 1980.

- Физическая география материков и океанов / Под общей ред. А. М. Рябчикова. — М.: Высшая школа, 1988.

- Нейман В. Г., Бурков В. А., Щербинин А. Д. Динамика вод Индийского океана. — М.: Научный мир, 1995. — С. 223. — ISBN 5-89176-023-1.

- Edward A. Alpers. The Indian Ocean in World History (англ.). — Oxford University Press, 2014. — ISBN 978-0-19-533787-7.

| Indian Ocean | |

|---|---|

Extent of the Indian Ocean according to International Hydrographic Organization |

|

|

Indian Ocean |

|

Topographic/bathymetric map of the Indian Ocean region |

|

| Coordinates | 20°S 80°E / 20°S 80°ECoordinates: 20°S 80°E / 20°S 80°E |

| Type | Ocean |

| Primary inflows | Zambezi, Ganges-Brahmaputra, Indus, Jubba, and Murray (largest 5) |

| Catchment area | 21,100,000 km2 (8,100,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | South and Southeast Asia, Western Asia, Northeast, East and Southern Africa and Australia |

| Max. length | 9,600 km (6,000 mi) (Antarctica to Bay of Bengal)[1] |

| Max. width | 7,600 km (4,700 mi) (Africa to Australia)[1] |

| Surface area | 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 3,741 m (12,274 ft) |

| Max. depth | 7,258 m (23,812 ft) (Java Trench) |

| Shore length1 | 66,526 km (41,337 mi)[2] |

| Islands | Maday Island, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Madagascar, Seychelles |

| Settlements | Cities, ports and harbours list |

| References | [3] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. |

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world’s five oceanic divisions, covering 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) or ~19.8% of the water on Earth’s surface.[4] It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by the Southern Ocean or Antarctica, depending on the definition in use.[5] Along its core, the Indian Ocean has some large marginal or regional seas such as the Arabian Sea, Laccadive Sea, Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea.

Etymology[edit]

The Indian Ocean has been known by its present name since at least 1515 when the Latin form Oceanus Orientalis Indicus (“Indian Eastern Ocean”) is attested, named after the Indian subcontinent, which projects into it. It was earlier known as the Eastern Ocean, a term that was still in use during the mid-18th century (see map), as opposed to the Western Ocean (Atlantic) before the Pacific was surmised.[6]

Conversely, Chinese explorers in the Indian Ocean during the 15th century called it the Western Oceans.[7]

In Ancient Greek geography, the Indian Ocean region known to the Greeks was called the Erythraean Sea.[8]

Geography[edit]

The ocean-floor of the Indian Ocean is divided by spreading ridges and crisscrossed by aseismic structures

A composite satellite image centred on the Indian Ocean

Extent and data[edit]

The borders of the Indian Ocean, as delineated by the International Hydrographic Organization in 1953 included the Southern Ocean but not the marginal seas along the northern rim, but in 2000 the IHO delimited the Southern Ocean separately, which removed waters south of 60°S from the Indian Ocean but included the northern marginal seas.[9][10] Meridionally, the Indian Ocean is delimited from the Atlantic Ocean by the 20° east meridian, running south from Cape Agulhas, and from the Pacific Ocean by the meridian of 146°49’E, running south from the southernmost point of Tasmania. The northernmost extent of the Indian Ocean (including marginal seas) is approximately 30° north in the Persian Gulf.[10]

The Indian Ocean covers 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi), including the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf but excluding the Southern Ocean, or 19.5% of the world’s oceans; its volume is 264,000,000 km3 (63,000,000 cu mi) or 19.8% of the world’s oceans’ volume; it has an average depth of 3,741 m (12,274 ft) and a maximum depth of 7,906 m (25,938 ft).[4]

All of the Indian Ocean is in the Eastern Hemisphere and the centre of the Eastern Hemisphere, the 90th meridian east, passes through the Ninety East Ridge.

Coasts and shelves[edit]

In contrast to the Atlantic and Pacific, the Indian Ocean is enclosed by major landmasses and an archipelago on three sides and does not stretch from pole to pole, and can be likened to an embayed ocean. It is centered on the Indian Peninsula. Although this subcontinent has played a significant role in its history, the Indian Ocean has foremostly been a cosmopolitan stage, interlinking diverse regions by innovations, trade, and religion since early in human history.[11]

The active margins of the Indian Ocean have an average width (horizontal distance from land to shelf break[12]) of 19 ± 0.61 km (11.81 ± 0.38 mi) with a maximum width of 175 km (109 mi). The passive margins have an average width of 47.6 ± 0.8 km (29.58 ± 0.50 mi).[13]

The average width of the slopes (horizontal distance from shelf break to foot of slope) of the continental shelves are 50.4–52.4 km (31.3–32.6 mi) for active and passive margins respectively, with a maximum width of 205.3–255.2 km (127.6–158.6 mi).[14]

In correspondence of the Shelf break, also known as Hinge zone, the Bouguer gravity ranges from 0 to 30 mGals that is unusual for a continental region of around 16 km thick sediments. It has been hypothesized that the “Hinge zone may represent the relict of continental and proto-oceanic crustal boundary formed during the rifting of India from Antarctica.”[15]

Australia, Indonesia, and India are the three countries with the longest shorelines and exclusive economic zones. The continental shelf makes up 15% of the Indian Ocean.

More than two billion people live in countries bordering the Indian Ocean, compared to 1.7 billion for the Atlantic and 2.7 billion for the Pacific (some countries border more than one ocean).[2]

Rivers[edit]

The Indian Ocean drainage basin covers 21,100,000 km2 (8,100,000 sq mi), virtually identical to that of the Pacific Ocean and half that of the Atlantic basin, or 30% of its ocean surface (compared to 15% for the Pacific). The Indian Ocean drainage basin is divided into roughly 800 individual basins, half that of the Pacific, of which 50% are located in Asia, 30% in Africa, and 20% in Australasia. The rivers of the Indian Ocean are shorter on average (740 km (460 mi)) than those of the other major oceans. The largest rivers are (order 5) the Zambezi, Ganges-Brahmaputra, Indus, Jubba, and Murray rivers and (order 4) the Shatt al-Arab, Wadi Ad Dawasir (a dried-out river system on the Arabian Peninsula) and Limpopo rivers.[16]

After the breakup of East Gondwana and the formation of the Himalayas, the Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers flow into the world’s largest delta known as the Bengal delta or Sunderbans.[15]

Marginal seas[edit]

Marginal seas, gulfs, bays and straits of the Indian Ocean include:[10]

Along the east coast of Africa, the Mozambique Channel separates Madagascar from mainland Africa, while the Sea of Zanj is located north of Madagascar.

On the northern coast of the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Aden is connected to the Red Sea by the strait of Bab-el-Mandeb. In the Gulf of Aden, the Gulf of Tadjoura is located in Djibouti and the Guardafui Channel separates Socotra island from the Horn of Africa. The northern end of the Red Sea terminates in the Gulf of Aqaba and Gulf of Suez. The Indian Ocean is artificially connected to the Mediterranean Sea without ship lock through the Suez Canal, which is accessible via the Red Sea.

The Arabian Sea is connected to the Persian Gulf by the Gulf of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz. In the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Bahrain separates Qatar from the Arabic Peninsula.

Along the west coast of India, the Gulf of Kutch and Gulf of Khambat are located in Gujarat in the northern end while the Laccadive Sea separates the Maldives from the southern tip of India.

The Bay of Bengal is off the east coast of India. The Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait separates Sri Lanka from India, while the Adam’s Bridge separates the two. The Andaman Sea is located between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Islands.

In Indonesia, the so-called Indonesian Seaway is composed of the Malacca, Sunda and Torres Straits.

The Gulf of Carpentaria of located on the Australian north coast while the Great Australian Bight constitutes a large part of its southern coast.[17][18][19]

- Arabian Sea – 3.862 million km2

- Bay of Bengal – 2.172 million km2

- Andaman Sea – 797,700 km2

- Laccadive Sea – 786,000 km2

- Mozambique Channel – 700,000 km2

- Timor Sea – 610,000 km2

- Red Sea – 438,000 km2

- Gulf of Aden – 410,000 km2

- Persian Gulf – 251,000 km2

- Flores Sea – 240,000 km2

- Molucca Sea – 200,000 km2

- Oman Sea – 181,000 km2

- Great Australian Bight – 45,926 km2

- Gulf of Aqaba – 239 km2

- Gulf of Khambhat

- Gulf of Kutch

- Gulf of Suez

Climate[edit]

During summer, warm continental masses draw moist air from the Indian Ocean hence producing heavy rainfall. The process is reversed during winter, resulting in dry conditions.

Several features make the Indian Ocean unique. It constitutes the core of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool which, when interacting with the atmosphere, affects the climate both regionally and globally. Asia blocks heat export and prevents the ventilation of the Indian Ocean thermocline. That continent also drives the Indian Ocean monsoon, the strongest on Earth, which causes large-scale seasonal variations in ocean currents, including the reversal of the Somali Current and Indian Monsoon Current. Because of the Indian Ocean Walker circulation there are no continuous equatorial easterlies. Upwelling occurs near the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula in the Northern Hemisphere and north of the trade winds in the Southern Hemisphere. The Indonesian Throughflow is a unique Equatorial connection to the Pacific.[20]

The climate north of the equator is affected by a monsoon climate. Strong north-east winds blow from October until April; from May until October south and west winds prevail. In the Arabian Sea, the violent Monsoon brings rain to the Indian subcontinent. In the southern hemisphere, the winds are generally milder, but summer storms near Mauritius can be severe. When the monsoon winds change, cyclones sometimes strike the shores of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.[21] Some 80% of the total annual rainfall in India occurs during summer and the region is so dependent on this rainfall that many civilisations perished when the Monsoon failed in the past. The huge variability in the Indian Summer Monsoon has also occurred pre-historically, with a strong, wet phase 33,500–32,500 BP; a weak, dry phase 26,000–23,500 BC; and a very weak phase 17,000–15,000 BP,

corresponding to a series of dramatic global events: Bølling-Allerød, Heinrich, and Younger Dryas.[22]

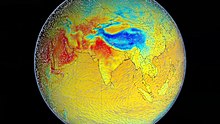

Air pollution in South Asia spread over the Bay of Bengal and beyond.

The Indian Ocean is the warmest ocean in the world.[23] Long-term ocean temperature records show a rapid, continuous warming in the Indian Ocean, at about 1.2 °C (34.2 °F) (compared to 0.7 °C (33.3 °F) for the warm pool region) during 1901–2012.[24] Research indicates that human induced greenhouse warming, and changes in the frequency and magnitude of El Niño (or the Indian Ocean Dipole), events are a trigger to this strong warming in the Indian Ocean.[24]

South of the Equator (20–5°S), the Indian Ocean is gaining heat from June to October, during the austral winter, while it is losing heat from November to March, during the austral summer.[25]

In 1999, the Indian Ocean Experiment showed that fossil fuel and biomass burning in South and Southeast Asia caused air pollution (also known as the Asian brown cloud) that reach as far as the Intertropical Convergence Zone at 60°S. This pollution has implications on both a local and global scale.[26]

Oceanography[edit]

Forty percent of the sediment of the Indian Ocean is found in the Indus and Ganges fans. The oceanic basins adjacent to the continental slopes mostly contain terrigenous sediments. The ocean south of the polar front (roughly 50° south latitude) is high in biologic productivity and dominated by non-stratified sediment composed mostly of siliceous oozes. Near the three major mid-ocean ridges the ocean floor is relatively young and therefore bare of sediment, except for the Southwest Indian Ridge due to its ultra-slow spreading rate.[27]

The ocean’s currents are mainly controlled by the monsoon. Two large gyres, one in the northern hemisphere flowing clockwise and one south of the equator moving anticlockwise (including the Agulhas Current and Agulhas Return Current), constitute the dominant flow pattern. During the winter monsoon (November–February), however, circulation is reversed north of 30°S and winds are weakened during winter and the transitional periods between the monsoons.[28]

The Indian Ocean contains the largest submarine fans of the world, the Bengal Fan and Indus Fan, and the largest areas of slope terraces and rift valleys.

[29]

The inflow of deep water into the Indian Ocean is 11 Sv, most of which comes from the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). The CDW enters the Indian Ocean through the Crozet and Madagascar basins and crosses the Southwest Indian Ridge at 30°S. In the Mascarene Basin the CDW becomes a deep western boundary current before it is met by a re-circulated branch of itself, the North Indian Deep Water. This mixed water partly flows north into the Somali Basin whilst most of it flows clockwise in the Mascarene Basin where an oscillating flow is produced by Rossby waves.[30]

Water circulation in the Indian Ocean is dominated by the Subtropical Anticyclonic Gyre, the eastern extension of which is blocked by the Southeast Indian Ridge and the 90°E Ridge. Madagascar and the Southwest Indian Ridge separate three cells south of Madagascar and off South Africa. North Atlantic Deep Water reaches into the Indian Ocean south of Africa at a depth of 2,000–3,000 m (6,600–9,800 ft) and flows north along the eastern continental slope of Africa. Deeper than NADW, Antarctic Bottom Water flows from Enderby Basin to Agulhas Basin across deep channels (<4,000 m (13,000 ft)) in the Southwest Indian Ridge, from where it continues into the Mozambique Channel and Prince Edward Fracture Zone.[31]

North of 20° south latitude the minimum surface temperature is 22 °C (72 °F), exceeding 28 °C (82 °F) to the east. Southward of 40° south latitude, temperatures drop quickly.[21]

The Bay of Bengal contributes more than half (2,950 km3 or 710 cu mi) of the runoff water to the Indian Ocean. Mainly in summer, this runoff flows into the Arabian Sea but also south across the Equator where it mixes with fresher seawater from the Indonesian Throughflow. This mixed freshwater joins the South Equatorial Current in the southern tropical Indian Ocean.[32]

Sea surface salinity is highest (more than 36 PSU) in the Arabian Sea because evaporation exceeds precipitation there. In the Southeast Arabian Sea salinity drops to less than 34 PSU. It is the lowest (c. 33 PSU) in the Bay of Bengal because of river runoff and precipitation. The Indonesian Throughflow and precipitation results in lower salinity (34 PSU) along the Sumatran west coast. Monsoonal variation results in eastward transportation of saltier water from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal from June to September and in westerly transport by the East India Coastal Current to the Arabian Sea from January to April.[33] It is found that Arabian Sea warming is in response to the reduction in lower monsoon circulation in recent decades.[34]

An Indian Ocean garbage patch was discovered in 2010 covering at least 5 million square kilometres (1.9 million square miles). Riding the southern Indian Ocean Gyre, this vortex of plastic garbage constantly circulates the ocean from Australia to Africa, down the Mozambique Channel, and back to Australia in a period of six years, except for debris that gets indefinitely stuck in the centre of the gyre.[35]

The garbage patch in the Indian Ocean will, according to a 2012 study, decrease in size after several decades to vanish completely over centuries. Over several millennia, however, the global system of garbage patches will accumulate in the North Pacific.[36]

There are two amphidromes of opposite rotation in the Indian Ocean, probably caused by Rossby wave propagation.[37]

Icebergs drift as far north as 55° south latitude, similar to the Pacific but less than in the Atlantic where icebergs reach up to 45°S. The volume of iceberg loss in the Indian Ocean between 2004 and 2012 was 24 Gt.[38]

Since the 1960s, anthropogenic warming of the global ocean combined with contributions of freshwater from retreating land ice causes a global rise in sea level. Sea level also increases in the Indian Ocean, except in the south tropical Indian Ocean where it decreases, a pattern most likely caused by rising levels of greenhouse gases.[39]

Marine life[edit]

A dolphin off Western Australia and a swarm of surgeonfish near Maldives Islands represents the well-known, exotic fauna of the warmer parts of the Indian Ocean. King Penguins on a beach in the Crozet Archipelago near Antarctica attract fewer tourists.

Among the tropical oceans, the western Indian Ocean hosts one of the largest concentrations of phytoplankton blooms in summer, due to the strong monsoon winds. The monsoonal wind forcing leads to a strong coastal and open ocean upwelling, which introduces nutrients into the upper zones where sufficient light is available for photosynthesis and phytoplankton production. These phytoplankton blooms support the marine ecosystem, as the base of the marine food web, and eventually the larger fish species. The Indian Ocean accounts for the second-largest share of the most economically valuable tuna catch.[40] Its fish are of great and growing importance to the bordering countries for domestic consumption and export. Fishing fleets from Russia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan also exploit the Indian Ocean, mainly for shrimp and tuna.[3]

Research indicates that increasing ocean temperatures are taking a toll on the marine ecosystem. A study on the phytoplankton changes in the Indian Ocean indicates a decline of up to 20% in the marine plankton in the Indian Ocean, during the past six decades. The tuna catch rates have also declined 50–90% during the past half-century, mostly due to increased industrial fisheries, with the ocean warming adding further stress to the fish species.[41]

Endangered and vulnerable marine mammals and turtles:[42]

| Name | Distribution | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Endangered | ||

| Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) |

Southwest Australia | Decreasing |

| Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) |

Global | Increasing |

| Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) |

Global | Increasing |

| Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) |

Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) |

Western Indian Ocean | Decreasing |

| Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) |

Global | Decreasing |

| Vulnerable | ||

| Dugong (Dugong dugon) |

Equatorial Indian Ocean and Pacific | Decreasing |

| Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) |

Global | Unknown |

| Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) |

Global | Increasing |

| Australian snubfin dolphin (Orcaella heinsohni) |

Northern Australia, New Guinea | Decreasing |

| Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) |

Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Indo-Pacific finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides) |

Northern Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Australian humpback dolphin (Sousa sahulensis) |

Northern Australia, New Guinea | Decreasing |

| Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) |

Global | Decreasing |

| Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) |

Global | Decreasing |

| Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) |

Global | Decreasing |

80% of the Indian Ocean is open ocean and includes nine large marine ecosystems: the Agulhas Current, Somali Coastal Current, Red Sea, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Gulf of Thailand, West Central Australian Shelf, Northwest Australian Shelf and Southwest Australian Shelf. Coral reefs cover c. 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi). The coasts of the Indian Ocean includes beaches and intertidal zones covering 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi) and 246 larger estuaries. Upwelling areas are small but important. The hypersaline salterns in India covers between 5,000–10,000 km2 (1,900–3,900 sq mi) and species adapted for this environment, such as Artemia salina and Dunaliella salina, are important to bird life.[43]

Left: Mangroves (here in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia) are the only tropical to subtropical forests adapted for a coastal environment. From their origin on the coasts of the Indo-Malaysian region, they have reached a global distribution.

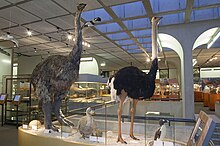

Right: The coelacanth (here a model from Oxford), thought extinct for million years, was rediscovered in the 20th century. The Indian Ocean species is blue whereas the Indonesian species is brown.

Coral reefs, sea grass beds, and mangrove forests are the most productive ecosystems of the Indian Ocean — coastal areas produce 20 tones per square kilometre of fish. These areas, however, are also being urbanised with populations often exceeding several thousand people per square kilometre and fishing techniques become more effective and often destructive beyond sustainable levels while the increase in sea surface temperature spreads coral bleaching.[44]

Mangroves covers 80,984 km2 (31,268 sq mi) in the Indian Ocean region, or almost half of the world’s mangrove habitat, of which 42,500 km2 (16,400 sq mi) is located in Indonesia, or 50% of mangroves in the Indian Ocean. Mangroves originated in the Indian Ocean region and have adapted to a wide range of its habitats but it is also where it suffers its biggest loss of habitat.[45]

In 2016, six new animal species were identified at hydrothermal vents in the Southwest Indian Ridge: a “Hoff” crab, a “giant peltospirid” snail, a whelk-like snail, a limpet, a scaleworm and a polychaete worm.[46]

The West Indian Ocean coelacanth was discovered in the Indian Ocean off South Africa in the 1930s and in the late 1990s another species, the Indonesian coelacanth, was discovered off Sulawesi Island, Indonesia. Most extant coelacanths have been found in the Comoros. Although both species represent an order of lobe-finned fishes known from the Early Devonian (410 mya) and though extinct 66 mya, they are morphologically distinct from their Devonian ancestors. Over millions of years, coelacanths evolved to inhabit different environments — lungs adapted for shallow, brackish waters evolved into gills adapted for deep marine waters.[47]

Biodiversity[edit]

Of Earth’s 36 biodiversity hotspot nine (or 25%) are located on the margins of the Indian Ocean.

- Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.[48]

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A “reverse colonisation”, from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the chameleons, for example, first diversified on Madagascar and then colonised Africa. Several species on the islands of the Indian Ocean are textbook cases of evolutionary processes; the dung beetles, day geckos, and lemurs are all examples of adaptive radiation.[citation needed]

Many bones (250 bones per square metre) of recently extinct vertebrates have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp in Mauritius, including bones of the Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) and Cylindraspis giant tortoise. An analysis of these remains suggests a process of aridification began in the southwest Indian Ocean began around 4,000 years ago.[49]

- Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (MPA); 8,100 (1,900 endemic) species of plants; 541 (0) birds; 205 (36) reptiles; 73 (20) freshwater fishes; 73 (11) amphibians; and 197 (3) mammals.[48]

Mammalian megafauna once widespread in the MPA was driven to near extinction in the early 20th century. Some species have been successfully recovered since then — the population of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) increased from less than 20 individuals in 1895 to more than 17,000 as of 2013. Other species still depend on fenced areas and management programs, including black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), cheetah (Acynonix jubatus), elephant (Loxodonta africana), and lion (Panthera leo).[50]

- Coastal forests of eastern Africa; 4,000 (1,750 endemic) species of plants; 636 (12) birds; 250 (54) reptiles; 219 (32) freshwater fishes; 95 (10) amphibians; and 236 (7) mammals.[48]

This biodiversity hotspot (and namesake ecoregion and “Endemic Bird Area”) is a patchwork of small forested areas, often with a unique assemblage of species within each, located within 200 km (120 mi) from the coast and covering a total area of c. 6,200 km2 (2,400 sq mi). It also encompasses coastal islands, including Zanzibar and Pemba, and Mafia.[51]

- Horn of Africa; 5,000 (2,750 endemic) species of plants; 704 (25) birds; 284 (93) reptiles; 100 (10) freshwater fishes; 30 (6) amphibians; and 189 (18) mammals.[48]

This area, one of the only two hotspots that are entirely arid, includes the Ethiopian Highlands, the East African Rift valley, the Socotra islands, as well as some small islands in the Red Sea and areas on the southern Arabic Peninsula. Endemic and threatened mammals include the dibatag (Ammodorcas clarkei) and Speke’s gazelle (Gazella spekei); the Somali wild ass (Equus africanus somaliensis) and hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas). It also contains many reptiles.[52]

In Somalia, the centre of the 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) hotspot, the landscape is dominated by Acacia-Commiphora deciduous bushland, but also includes the Yeheb nut (Cordeauxia edulus) and species discovered more recently such as the Somali cyclamen (Cyclamen somalense), the only cyclamen outside the Mediterranean. Warsangli linnet (Carduelis johannis) is an endemic bird found only in northern Somalia. An unstable political situation and mismanagement has resulted in overgrazing which has produced one of the most degraded hotspots where only c. 5 % of the original habitat remains.[53]

- The Western Ghats–Sri Lanka; 5,916 (3,049 endemic) species of plants; 457 (35) birds; 265 (176) reptiles; 191 (139) freshwater fishes; 204 (156) amphibians; and 143 (27) mammals.[48]

Encompassing the west coast of India and Sri Lanka, until c. 10,000 years ago a landbridge connected Sri Lanka to the Indian Subcontinent, hence this region shares a common community of species.[54]

- Indo-Burma; 13.500 (7,000 endemic) species of plants; 1,277 (73) birds; 518 (204) reptiles; 1,262 (553) freshwater fishes; 328 (193) amphibians; and 401 (100) mammals.[48]

Indo-Burma encompasses a series of mountain ranges, five of Asia’s largest river systems, and a wide range of habitats. The region has a long and complex geological history, and long periods rising sea levels and glaciations have isolated ecosystems and thus promoted a high degree of endemism and speciation. The region includes two centres of endemism: the Annamite Mountains and the northern highlands on the China-Vietnam border.[55]

Several distinct floristic regions, the Indian, Malesian, Sino-Himalayan, and Indochinese regions, meet in a unique way in Indo-Burma and the hotspot contains an estimated 15,000–25,000 species of vascular plants, many of them endemic.[56]

- Sundaland; 25,000 (15,000 endemic) species of plants; 771 (146) birds; 449 (244) reptiles; 950 (350) freshwater fishes; 258 (210) amphibians; and 397 (219) mammals.[48]

Sundaland encompasses 17,000 islands of which Borneo and Sumatra are the largest. Endangered mammals include the Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, the proboscis monkey, and the Javan and Sumatran rhinoceroses.[57]

- Wallacea; 10,000 (1,500 endemic) species of plants; 650 (265) birds; 222 (99) reptiles; 250 (50) freshwater fishes; 49 (33) amphibians; and 244 (144) mammals.[48]

- Southwest Australia; 5,571 (2,948 endemic) species of plants; 285 (10) birds; 177 (27) reptiles; 20 (10) freshwater fishes; 32 (22) amphibians; and 55 (13) mammals.[48]

Stretching from Shark Bay to Israelite Bay and isolated by the arid Nullarbor Plain, the southwestern corner of Australia is a floristic region with a stable climate in which one of the world’s largest floral biodiversity and an 80% endemism has evolved. From June to September it is an explosion of colours and the Wildflower Festival in Perth in September attracts more than half a million visitors.[58]

Geology[edit]

Left: The oldest ocean floor of the Indian Ocean formed c. 150 Ma when the Indian Subcontinent and Madagascar broke-up from Africa. Right: The India–Asia collision c. 40 Ma completed the closure of the Tethys Ocean (grey areas north of India). Geologically, the Indian Ocean is the ocean floor that opened up south of India.

As the youngest of the major oceans,[59] the Indian Ocean has active spreading ridges that are part of the worldwide system of mid-ocean ridges. In the Indian Ocean these spreading ridges meet at the Rodrigues Triple Point with the Central Indian Ridge, including the Carlsberg Ridge, separating the African Plate from the Indian Plate; the Southwest Indian Ridge separating the African Plate from the Antarctic Plate; and the Southeast Indian Ridge separating the Australian Plate from the Antarctic Plate. The Central Indian Ridge is intercepted by the Owen Fracture Zone.[60]

Since the late 1990s, however, it has become clear that this traditional definition of the Indo-Australian Plate cannot be correct; it consists of three plates — the Indian Plate, the Capricorn Plate, and Australian Plate — separated by diffuse boundary zones.[61]

Since 20 Ma the African Plate is being divided by the East African Rift System into the Nubian and Somalia plates.[62]

There are only two trenches in the Indian Ocean: the 6,000 km (3,700 mi)-long Java Trench between Java and the Sunda Trench and the 900 km (560 mi)-long Makran Trench south of Iran and Pakistan.[60]

A series of ridges and seamount chains produced by hotspots pass over the Indian Ocean. The Réunion hotspot (active 70–40 million years ago) connects Réunion and the Mascarene Plateau to the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and the Deccan Traps in north-western India; the Kerguelen hotspot (100–35 million years ago) connects the Kerguelen Islands and Kerguelen Plateau to the Ninety East Ridge and the Rajmahal Traps in north-eastern India; the Marion hotspot (100–70 million years ago) possibly connects Prince Edward Islands to the Eighty Five East Ridge.[63] These hotspot tracks have been broken by the still active spreading ridges mentioned above.[60]

There are fewer seamounts in the Indian Ocean than in the Atlantic and Pacific. These are typically deeper than 3,000 m (9,800 ft) and located north of 55°S and west of 80°E. Most originated at spreading ridges but some are now located in basins far away from these ridges. The ridges of the Indian Ocean form ranges of seamounts, sometimes very long, including the Carlsberg Ridge, Madagascar Ridge, Central Indian Ridge, Southwest Indian Ridge, Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, 85°E Ridge, 90°E Ridge, Southeast Indian Ridge, Broken Ridge, and East Indiaman Ridge. The Agulhas Plateau and Mascarene Plateau are the two major shallow areas.[31]

The opening of the Indian Ocean began c. 156 Ma when Africa separated from East Gondwana. The Indian Subcontinent began to separate from Australia-Antarctica 135–125 Ma and as the Tethys Ocean north of India began to close 118–84 Ma the Indian Ocean opened behind it.[60]

History[edit]

The Indian Ocean, together with the Mediterranean, has connected people since ancient times, whereas the Atlantic and Pacific have had the roles of barriers or mare incognitum. The written history of the Indian Ocean, however, has been Eurocentric and largely dependent on the availability of written sources from the European colonial era. This history is often divided into an ancient period followed by an Islamic period; the subsequent periods are often subdivided into Portuguese, Dutch, and British periods.[64]

A concept of an “Indian Ocean World” (IOW), similar to that of the “Atlantic World”, exists but emerged much more recently and is not well established. The IOW is, nevertheless, sometimes referred to as the “first global economy” and was based on the monsoon which linked Asia, China, India, and Mesopotamia. It developed independently from the European global trade in the Mediterranean and Atlantic and remained largely independent from them until European 19th-century colonial dominance.[65]

The diverse history of the Indian Ocean is a unique mix of cultures, ethnic groups, natural resources, and shipping routes. It grew in importance beginning in the 1960s and 1970s and, after the Cold War, it has undergone periods of political instability, most recently with the emergence of India and China as regional powers.[66]

First settlements[edit]

According to the Coastal hypothesis, modern humans spread from Africa along the northern rim of the Indian Ocean.

Pleistocene fossils of Homo erectus and other pre–H. sapiens hominid fossils, similar to H. heidelbergensis in Europe, have been found in India. According to the Toba catastrophe theory, a supereruption c. 74,000 years ago at Lake Toba, Sumatra, covered India with volcanic ashes and wiped out one or more lineages of such archaic humans in India and Southeast Asia.[67]

The Out of Africa theory states that Homo sapiens spread from Africa into mainland Eurasia. The more recent Southern Dispersal or Coastal hypothesis instead advocates that modern humans spread along the coasts of the Arabic Peninsula and southern Asia. This hypothesis is supported by mtDNA research which reveals a rapid dispersal event during the Late Pleistocene (11,000 years ago). This coastal dispersal, however, began in East Africa 75,000 years ago and occurred intermittently from estuary to estuary along the northern perimeter of the Indian Ocean at a rate of 0.7–4.0 km (0.43–2.49 mi) per year. It eventually resulted in modern humans migrating from Sunda over Wallacea to Sahul (Southeast Asia to Australia).[68] Since then, waves of migration have resettled people and, clearly, the Indian Ocean littoral had been inhabited long before the first civilisations emerged. 5000–6000 years ago six distinct cultural centres had evolved around the Indian Ocean: East Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, South East Asia, the Malay World and Australia; each interlinked to its neighbours.[69]