| Серная кислота | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

| Общие | ||

| Систематическое наименование |

Серная кислота | |

| Традиционные названия | Серная кислота | |

| Хим. формула | H2SO4 | |

| Рац. формула | H2SO4 | |

| Физические свойства | ||

| Состояние | Жидкость | |

| Молярная масса | 98,078 ± 0,006 г/моль | |

| Плотность | 1,8356 г/см³ | |

| Динамическая вязкость | 21 мПа·с[2] | |

| Термические свойства | ||

| Температура | ||

| • плавления | +10,38 °C | |

| • кипения | +337 °C | |

| • разложения | +450 °C | |

| Удельная теплота плавления | 10,73 Дж/кг | |

| Давление пара | 0,001 ± 0,001 мм рт.ст.[3] | |

| Химические свойства | ||

Константа диссоциации кислоты  |

-3 | |

| Растворимость | ||

| • в воде | Растворима | |

| Оптические свойства | ||

| Показатель преломления | 1.397 | |

| Структура | ||

| Дипольный момент | 2.72 Д | |

| Классификация | ||

| Рег. номер CAS | 7664-93-9 | |

| PubChem | 1118 | |

| Рег. номер EINECS | 231-639-5 | |

| SMILES |

OS(O)(=O)=O |

|

| InChI |

InChI=1S/H2O4S/c1-5(2,3)4/h(H2,1,2,3,4) QAOWNCQODCNURD-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

|

| Кодекс Алиментариус | E513 | |

| RTECS | WS5600000 | |

| ChEBI | 26836 | |

| Номер ООН | 1830 | |

| ChemSpider | 1086 | |

| Безопасность | ||

| Предельная концентрация | 1 мг/м3 | |

| ЛД50 | 100 мг/кг | |

| Токсичность | 2-й класс опасности[1], общетоксическое действие. | |

| Краткие характер. опасности (H) |

H290, H314 |

|

| Меры предостор. (P) |

P280, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P305+P351+P338, P308+P311 |

|

| Сигнальное слово | опасно | |

| Пиктограммы СГС |

|

|

| NFPA 704 |

0 3 2

|

|

| Приведены данные для стандартных условий (25 °C, 100 кПа), если не указано иное. | ||

Се́рная кислота́ (химическая формула — H2SO4) — сильная неорганическая кислота, отвечающая высшей степени окисления серы (+6).

При обычных условиях концентрированная серная кислота — тяжёлая маслянистая жидкость без цвета и запаха, с сильнокислым «медным» вкусом. В технике серной кислотой называют её смеси как с водой, так и с серным ангидридом SO3. Если молярное отношение SO3 : H2O < 1, то это водный раствор серной кислоты, если > 1 — раствор SO3 в серной кислоте (олеум). Токсична в больших дозах[4], обладает исключительно сильной коррозионной активностью.

Название[править | править код]

В XVIII—XIX веках серу для пороха производили из серного колчедана (пирит) на купоросных заводах. Серную кислоту в то время называли «купоросным маслом»[5][6], очевидно отсюда происхождение названия её солей (а точнее именно кристаллогидратов) — купоросы.

Исторические сведения[править | править код]

Серная кислота известна с древности, она встречается в природе в свободном виде, например, в виде озёр вблизи вулканов. Возможно, первое упоминание о кислых газах, получаемых при прокаливании квасцов или железного купороса «зеленого камня», встречается в сочинениях, приписываемых арабскому алхимику Джабир ибн Хайяну.

В IX веке персидский алхимик Ар-Рази, прокаливая смесь железного и медного купороса (FeSO4•7H2O и CuSO4•5H2O), также получил раствор серной кислоты. Этот способ усовершенствовал европейский алхимик Альберт Магнус, живший в XIII веке.

Схема получения серной кислоты из железного купороса — термическое разложение сульфата железа (II) с последующим охлаждением смеси[7]

В трудах алхимика Василия Валентина (XVI век) описывается способ получения серной кислоты путём поглощения водой газа (серный ангидрид), выделяющегося при сжигании смеси порошков серы и селитры. Впоследствии этот способ лег в основу т. н. «камерного» способа, осуществляемого в небольших камерах, облицованных свинцом, который не растворяется в серной кислоте. В СССР такой способ просуществовал вплоть до 1955 г.

Алхимикам XV века в известен был также способ получения серной кислоты из пирита — серного колчедана, более дешёвого и распространенного сырья, чем сера. Таким способом получали серную кислоту на протяжении 300 лет, небольшими количествами в стеклянных ретортах. Впоследствии, в связи с развитием катализа этот метод вытеснил камерный способ синтеза серной кислоты. В настоящее время серную кислоту получают каталитическим окислением (на V2O5) оксида серы (IV) в оксид серы (VI), и последующим растворением оксида серы (VI) в 70 % серной кислоте с образованием олеума.

В России производство серной кислоты впервые было организовано в 1805 году под Москвой в Звенигородском уезде. В 1913 году Россия по производству серной кислоты занимала 13 место в мире.[8]

Физические и физико-химические свойства[править | править код]

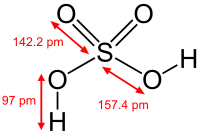

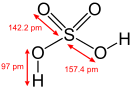

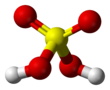

Серная кислота — это очень сильная двухосновная кислота, при 18оС pKa (1) = −2,8, pKa (2) = 1,92 (К₂ 1,2 10−2); длины связей в молекуле S=O 0,143 нм, S—OH 0,154 нм, угол HOSOH 104°, OSO 119°; кипит, образуя азеотропную смесь (98,3 % H2SO4 и 1,7 % H2О с температурой кипения 338,8оС). Смешивается с водой и SO3, во всех соотношениях. В водных растворах серная кислота практически полностью диссоциирует на H3О+, HSO3+, и 2НSO₄−. Образует гидраты H2SO4·nH2O, где n = 1, 2, 3, 4 и 6,5.

| H2SO4 | HSO4− | H3SO4+ | H3O+ | HS2O7⁻ | H2S2O7 | |

| состав, % | 99,5 | 0,18 | 0,14 | 0,09 | 0,05 | 0,04 |

Олеум[править | править код]

Основная статья: Олеум

Растворы серного ангидрида SO3 в серной кислоте называются олеумом, они образуют два соединения H2SO4·SO3 и H2SO4·2SO3.

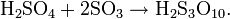

Олеум содержит также пиросерные кислоты, образующиеся по реакциям:

-

Сульфит

Температура кипения водных растворов серной кислоты повышается с ростом её концентрации и достигает максимума при содержании 98,3 % H2SO4.

| Содержание % по массе | Плотность при 20 °C, г/см3 | Температура плавления, °C | Температура кипения, °C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2SO4 | SO3 (свободный) | |||

| 10 | – | 1,0661 | −5,5 | 102,0 |

| 20 | – | 1,1394 | −19,0 | 104,4 |

| 40 | – | 1,3028 | −65,2 | 113,9 |

| 60 | – | 1,4983 | −25,8 | 141,8 |

| 80 | – | 1,7272 | −3,0 | 210,2 |

| 98 | – | 1,8365 | 0,1 | 332,4 |

| 100 | – | 1,8305 | 10,4 | 296,2 |

| 104,5 | 20 | 1,8968 | −11,0 | 166,6 |

| 109 | 40 | 1,9611 | 33,3 | 100,6 |

| 113,5 | 60 | 2,0012 | 7,1 | 69,8 |

| 118,0 | 80 | 1,9947 | 16,9 | 55,0 |

| 122,5 | 100 | 1,9203 | 16,8 | 44,7 |

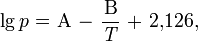

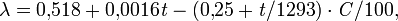

Температура кипения олеума с увеличением содержания SO3 понижается. При увеличении концентрации водных растворов серной кислоты общее давление пара над растворами понижается и при содержании 98,3 % H2SO4 достигает минимума. С увеличением концентрации SO3 в олеуме общее давление пара над ним повышается. Давление пара над водными растворами серной кислоты и олеума можно вычислить по уравнению:

величины коэффициентов А и В зависят от концентрации серной кислоты. Пар над водными растворами серной кислоты состоит из смеси паров воды, H2SO4 и SO3, при этом состав пара отличается от состава жидкости при всех концентрациях серной кислоты, кроме соответствующей азеотропной смеси.

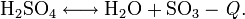

С повышением температуры усиливается диссоциация:

Уравнение температурной зависимости константы равновесия:

При нормальном давлении степень диссоциации: 10−5 (373 К), 2,5 (473 К), 27,1 (573 К), 69,1 (673 К).

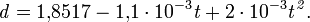

Плотность 100%-ной серной кислоты можно определить по уравнению:

С повышением концентрации растворов серной кислоты их теплоемкость уменьшается и достигает минимума для 100%-ной серной кислоты, теплоемкость олеума с повышением содержания SO3 увеличивается.

При повышении концентрации и понижении температуры теплопроводность λ уменьшается:

где С — концентрация серной кислоты, в %.

Максимальную вязкость имеет олеум H2SO4·SO3, с повышением температуры η снижается. Для олеума минимальное ρ при концентрации 10 % SO3. С повышением температуры ρ серной кислоты увеличивается. Диэлектрическая проницаемость 100%-ной серной кислоты 101 (298,15 К), 122 (281,15 К); криоскопическая постоянная 6,12, эбулиоскопическая постоянная 5,33; коэффициент диффузии пара серной кислоты в воздухе изменяется в зависимости от температуры; D = 1,67·10−5T3/2 см2/с.

| ω, % | 5 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ H2SO4, г/мл | 1,03 | 1,064 | 1,1365 | 1,215 | 1,2991 | 1,3911 | 1,494 | 1,6059 | 1,7221 | 1,7732 | 1,7818 | 1,7897 | 1,7968 | 1,8033 | 1,8091 | 1,8142 | 1,8188 | 1,8227 | 1,826 | 1,8286 | 1,8305 | 1,8314 | 1,831 | 1,8292 | 1,8255 |

Химические свойства[править | править код]

Серная кислота в концентрированном виде при нагревании — довольно сильный окислитель.

1. Окисляет HI и частично HBr до свободных галогенов:

-

ΔH° = −561.9 кДж/моль (экзотермическая)[10] ΔG° = −305.4 кДж/моль (экзэргоническая)[10]

-

ΔH° = 18.14 кДж/моль (эндотермическая)[11] ΔS° = −14.95 Дж/моль (экзоэнтропическая)[11] ΔG° = 22.5 кДж/моль (эндэргоническая)[11]

Углерод до CO2, серу — до SO2.

- Окисляет угарный газ до углекислого.

2. Окисляет многие металлы (исключения: Au, Pt, Ir, Rh, Ta). При этом концентрированная серная кислота восстанавливается до диоксида серы, например[12]:

3. На холоде в концентрированной серной кислоте Fe, Al, Cr, Co, Ni, Ba пассивируются, и реакции не протекают.

Наиболее сильными восстановителями концентрированная серная кислота восстанавливается до серы и сероводорода. Концентрированная серная кислота поглощает водяные пары, поэтому она применяется для сушки газов, жидкостей и твёрдых тел, например, в эксикаторах. Однако концентрированная H2SO4 частично восстанавливается водородом, из-за чего не может применяться для его сушки. Отщепляя воду от органических соединений и оставляя при этом чёрный углерод (уголь), концентрированная серная кислота приводит к обугливанию древесины, сахара и других веществ[12].

4. Разбавленная H2SO4 взаимодействует со всеми металлами, находящимися в электрохимическом ряду напряжений левее водорода с его выделением, например[12]:

5. Окислительные свойства для разбавленной H2SO4 нехарактерны. Серная кислота образует два ряда солей: средние — сульфаты и кислые — гидросульфаты, а также эфиры. Известны пероксомоносерная (или кислота Каро) H2SO5 и пероксодисерная H2S2O8 кислоты.

6. Серная кислота реагирует с основными оксидами, образуя сульфат металла и воду:

7. На металлообрабатывающих заводах раствор серной кислоты применяют для удаления слоя оксида металла с поверхности металлических изделий, подвергающихся в процессе изготовления сильному нагреванию. Так, оксид железа удаляется с поверхности листового железа действием нагретого раствора серной кислоты:

8. Концентрированная H2SO4 превращает некоторые органические вещества в другие соединения углерода:

9. Качественная реакция на серную кислоту и её растворимые соли — это их взаимодействие с растворимыми солями бария, при котором образуется белый осадок сульфата бария, нерастворимый в воде и кислотах, например[13]:

Получение серной кислоты[править | править код]

Промышленный (контактный) способ[править | править код]

В промышленности серную кислоту получают окислением диоксида серы (сернистый газ, образующийся в процессе сжигания элементарной серы, серного колчедана или сероводород-содержащих газов, поступающих с установок гидроочистки и систем отпарки кислых стоков) до триоксида (серного ангидрида) на твёрдом ванадиевом катализаторе в четыре ступени (данная реакция экзотермична, поэтому применяется промежуточное охлаждение после первого слоя с помощью трубных пучков, через которые подаётся воздух, и после следующих двух ступеней — с помощью кольцевой трубы, имеющей большой диаметр, через которую подаётся воздух, над которой расположен дефлектор. Воздух нагнетается воздуходувками, часть горячего воздуха подаётся на горелочные устройства котлов, в которых производится сжигание сероводородсодержащих газов) последующим охлаждением и взаимодействием SO3 с водой. Получаемую данным способом серную кислоту также называют «контактной» (концентрация 92-94 %).

Нитрозный (башенный) способ[править | править код]

Раньше серную кислоту получали исключительно нитрозным методом в специальных башнях, а кислоту называли «башенной» (концентрация 75 %). Сущность этого метода заключается в окислении диоксида серы диоксидом азота в присутствии воды. Именно таким способом произошла реакция в воздухе Лондона во время Великого смога.

Лабораторные методы[править | править код]

В лаборатории можно получить серную кислоту взаимодействием сероводорода, элементарной серы и диоксида серы с хлорной или бромной водой или пероксидом водорода:

Также её можно получить взаимодействием диоксида серы с кислородом и водой при +70 °C под давлением в присутствии сульфата меди (II):

Применение[править | править код]

Серную кислоту применяют:

- в обработке руд, особенно при добыче редких элементов, в том числе урана, иридия, циркония, осмия и т. п.;

- в производстве минеральных удобрений;

- в качестве электролита в свинцовых аккумуляторах;

- для получения различных минеральных кислот и солей;

- в производстве химических волокон, красителей, дымообразующих и взрывчатых веществ;

- в нефтяной, металлообрабатывающей, текстильной, кожевенной и др. отраслях промышленности;

- в пищевой промышленности — зарегистрирована в качестве пищевой добавки E513 (эмульгатор);

- в промышленном органическом синтезе в реакциях:

- дегидратации (получение диэтилового эфира, сложных эфиров);

- гидратации (этанола из этилена);

- сульфирования (синтетические моющие средства и промежуточные продукты в производстве красителей);

- алкилирования (получение изооктана, полиэтиленгликоля, капролактама) и др.;

- восстановления смол в фильтрах на производстве дистиллированной воды.

Мировое производство серной кислоты около 200 млн тонн в год[14]. Самый крупный потребитель серной кислоты — производство минеральных удобрений. На P2O5 фосфорных удобрений расходуется в 2,2—3,4 раза больше по массе серной кислоты, а на (NH4)2SO4 серной кислоты 75 % от массы расходуемого (NH4)2SO4. Поэтому сернокислотные заводы стремятся строить в комплексе с заводами по производству минеральных удобрений.

Токсическое действие[править | править код]

Серная кислота и олеум — очень едкие вещества, поражающие все ткани организма. При вдыхании паров этих веществ они вызывают затруднение дыхания, кашель, нередко — ларингит, трахеит, бронхит и т. д. Попадание кислоты на глаза в высокой концентрации может привести как к конъюнктивиту, так и к полной потере зрения[15].

Предельно допустимая концентрация (ПДК) паров серной кислоты в воздухе рабочей зоны 1 мг/м3, в атмосферном воздухе 0,3 мг/м3 (максимальная разовая) и 0,1 мг/м3 (среднесуточная). Поражающая концентрация паров серной кислоты 0,008 мг/л (экспозиция 60 мин), смертельная 0,18 мг/л (60 мин).

Серная кислота — токсичное вещество. В соответствии с ГОСТ 12.1.007-76 серная кислота является токсичным высокоопасным веществом[16] по воздействию на организм, 2-го класса опасности.

Аэрозоль серной кислоты может образовываться в атмосфере в результате выбросов химических и металлургических производств, содержащих оксиды серы и выпадать в виде кислотных дождей.

В России оборот серной кислоты концентрации 45 % и более — законодательно ограничен[17].

Дополнительные сведения[править | править код]

Мельчайшие капельки серной кислоты могут образовываться в средних и верхних слоях атмосферы в результате реакции водяного пара и вулканического пепла, содержащего большие количества серы. Получившаяся взвесь из-за высокого альбедо облаков серной кислоты, затрудняет доступ солнечных лучей к поверхности планеты. Поэтому (а также в результате большого количества мельчайших частиц вулканического пепла в верхних слоях атмосферы, также затрудняющих доступ солнечному свету к планете) после особо сильных вулканических извержений могут произойти значительные изменения климата. Например, в результате извержения вулкана Ксудач (Полуостров Камчатка, 1907 г.) повышенная концентрация пыли в атмосфере держалась около 2 лет, а характерные серебристые облака серной кислоты наблюдались даже в Париже[18]. Взрыв вулкана Пинатубо в 1991 году, отправивший в атмосферу 3⋅107 тонн серы, привёл к тому, что 1992 и 1993 года были значительно холоднее, чем 1991 и 1994[19].

Стандарты[править | править код]

- Кислота серная техническая ГОСТ 2184—77

- Кислота серная аккумуляторная. Технические условия ГОСТ 667—73

- Кислота серная особой чистоты. Технические условия ГОСТ 14262—78

- Реактивы. Кислота серная. Технические условия ГОСТ 4204—77

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Кислота серная техническая ГОСТ 2184—77

- ↑ Encyclopedia of chemical technology (англ.) / R. E. Kirk, D. Othmer

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0577.html

- ↑ name=https://docs.cntd.ru_Серная кислота

- ↑ Ушакова Н. Н., Фигурновский Н. А. Василий Михайлович Севергин: (1765—1826) / Ред. И. И. Шафрановский. М.: Наука, 1981. C. 59.

- ↑ См. также Каменное масло

- ↑ Эпштейн, 1979, с. 40.

- ↑ Эпштейн, 1979, с. 41.

- ↑ Density-Concentration Calculator (англ.). Дата обращения: 21 декабря 2021. Архивировано 21 декабря 2021 года.

- ↑ 1 2 sulfuric acid hydrogen iodide -> iodine H2S water – Wolfram|Alpha (англ.). www.wolframalpha.com. Дата обращения: 19 мая 2022.

- ↑ 1 2 3 sulfuric acid hydrogen bromide -> bromine sulfur dioxide water – Wolfram|Alpha (англ.). www.wolframalpha.com. Дата обращения: 19 мая 2022.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Ходаков Ю.В., Эпштейн Д.А., Глориозов П.А. § 91. Химические свойства серной кислоты // Неорганическая химия: Учебник для 7—8 классов средней школы. — 18-е изд. — М.: Просвещение, 1987. — С. 209—211. — 240 с. — 1 630 000 экз.

- ↑ Ходаков Ю.В., Эпштейн Д.А., Глориозов П.А. § 92. Качественная реакция на серную кислоту и её соли // Неорганическая химия: Учебник для 7—8 классов средней школы. — 18-е изд. — М.: Просвещение, 1987. — С. 212. — 240 с. — 1 630 000 экз.

- ↑ Sulfuric acid (англ.) // «The Essential Chemical Industry — online»

- ↑ SULFURIC ACID | CAMEO Chemicals | NOAA. cameochemicals.noaa.gov. Дата обращения: 22 мая 2020.

- ↑ name=https://docs.cntd.ru_ГОСТ (недоступная ссылка) 12.1.007-76. ССБТ. Вредные вещества. Классификация и общие требования

- ↑ Постановление Правительства Российской Федерации от 3 июня 2010 года № 398. Дата обращения: 30 мая 2016. Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2016 года.

- ↑ см. статью «Вулканы и климат» Архивная копия от 28 сентября 2007 на Wayback Machine (рус.)

- ↑ Русский архипелаг — Виновато ли человечество в глобальном изменении климата? Архивная копия от 1 декабря 2007 на Wayback Machine (рус.)

Литература[править | править код]

- Справочник сернокислотчика [Текст] / А. С. Ленский, П. А. Семенов, Г. А. Максудов; ред. К. М. Малин. — 2 изд., перераб. и доп. — М.: Химия, 1971. — 744 с. — Библиогр. в конце разд.- Предм. указ.: с. 723—744.

- Эпштейн Д. А. Общая химическая технология. — М.: Химия, 1979. — 312 с.

Ссылки[править | править код]

- Статья «Серная кислота» (Химическая энциклопедия)

- Плотность и значение pH серной кислоты при t=20 °C

Формула серной кислоты

ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЕ

Серная кислота (жирное масло) представляет собой сильную минеральную двухосновную кислоту, содержащую атом серы в наивысшей степени окисления (+6).

Химическая и структурная формула серной кислоты

Химическая формула: (

mathrm{H} 2 mathrm{SO} 4

)

Молекулярный вес: 98,078 г / моль.

Физические свойства серной кислоты

В нормальных условиях это тяжелая жирная жидкость без цвета или запаха (может иметь желтоватый оттенок) с кислым «медным» вкусом. Температура кристаллизации чистой серной кислоты составляет + 10 ° С.

Неограниченное смешивание с водой с выделением большого количества тепла, поэтому, чтобы избежать «кипения» раствора, всегда следует добавлять серную кислоту в воду, а не наоборот.

Раствор (

mathrm{SO} 3

) в серной кислоте называют олеумом. Олеум содержит пиросульфовые кислоты, образованные реакциями:

Серная кислота представляет собой сильную кислоту, константу диссоциации Ka = 103. Формирует среду и кислотные соли – сульфаты и гидросульфаты.

Химические свойства серной кислоты

Разбавленная серная кислота проявляет типичные кислотные свойства:

реагирует с металлами в электрохимической серии напряжений на водород с образованием сульфатов и высвобождением водорода:

(

Z n+H_{2} S O_{4}=Z n S O_{4}+H_{2} uparrow

)

реагирует с основными оксидами:

(

MgO+H_{2} S O_{4}=M g S O_{4}+H_{2}O

)

и основаниями для образования соответствующей соли и воды:

(

2NaOH+H_{2} S O_{4}=N a S O_{4}+2H_{2}O

)

вытесняет более слабые кислоты из их солей:

(

H_{2} S O_{4}+CH_{3} COON_{a} rightarrow N a HS O_{4}+CH_{3}COOH

)

Концентрированная серная кислота активно поглощает водяной пар, способна вытеснять воду из органических соединений с образованием углерода, воды и тепла (обугливая сахар):

(

C_{12} H_{22}O{11}(сахароза)+H{2}SO_{4}(конц) rightarrow 12C(уголь)+11 H_{2}O+H_{2}SO_{4}

)

Концентрированная серная кислота является очень сильным окислителем:

окисляет металлы, независимо от их положения в серии напряжений (кроме золота и платины), при этом уменьшается до SO2. Водород не выпускается.

(

Cu+2H{2}SO_{4}(конц) = CuSO_{4}+SO_{2}+2H_{2}O

)

(

Zn+2H{2}SO_{4}(конц) = ZnSO_{4}+SO_{2}+2H_{2}O

)

реагирует с неметаллами:

(

S+2H{2}SO_{4}(конц) = 3SO_{2}+2H_{2}O

)

с оксидами неметаллических металлов:

(

CO+H_{2}SO_{4}= CO_{2}+SO_{2}+H_{2}O

)

с неокисляющими кислотами:

(

2HCl+H_{2}SO_{4}= Cl_{2}+SO_{2}+2H_{2}O

)

Качественная реакция на сульфатно-ионное взаимодействие с растворимыми солями бария с образованием нерастворимых в воде и кислоте белого осадка сульфата бария:

(

H_{2}SO_{4}+BaCl_{2}= BaSO_{4} downarrow +2HCl

)

Концентрированная серная кислота является очень едким веществом. При воздействии на живую ткань он обезвоживает углеводороды, высвобождая избыточное тепло, что приводит к вторичному термическому ожогу в дополнение к химическому ожогу. Поэтому ущерб, вызванный серной кислотой, потенциально опаснее, чем ущерб, вызванный другими кислотами.

ПРИМЕР

К 3 л воды добавляли 2 мл 96% -ной серной кислоты, плотность которой составляла 1,84 г / мл. Вычислите рН полученного раствора.

Серная кислота является сильной кислотой, полностью диссоциирует в растворе в ионы:

(

H_{2} S O_{4} rightarrow 2 H^{+}+S O_{4}^{2-}

)

Рассчитайте массу раствора серной кислоты:

(

mleft(p-p a H_{2} S O_{4}right)=rho cdot V=1,84 cdot 2=3,68г

)

Рассчитайте массу серной кислоты в растворе:

(

mleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)=frac{mleft(p-p a H_{2} S O_{4}right) omegaleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)}{100}=frac{3,68 cdot 96}{100}=3,53_{Gamma}

)

Молярная масса серной кислоты составляет 98 г / моль.

Найдите количество вещества серной кислоты в растворе:

(

nleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)=frac{mleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)}{Mleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)}=frac{3,53}{98}=0,036моль

)

Общий объем решения будет равен:

(

V=Vleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)+Vleft(H_{2} Oright)=0,002+3=3,002л

)

Рассчитайте молярную концентрацию серной кислоты:

(

C_{M}left(H_{2} S O_{4}right)=frac{nleft(H_{2} S O_{4}right)}{V}=frac{0,036}{3,002}=0,012 моль/л

)

Из уравнения реакции для диссоциации серной кислоты следует, что концентрация ионов водорода равна:

(

left[H^{+}right]=2 C_{M}left(H_{2} S O_{4}right)=2 cdot 0,012=0,024

моль/л)

Рассчитайте pH полученного раствора:

(

p H=-l gleft[H^{+}right]=-l g 0,024=1,62

)

Значение рН полученного раствора серной кислоты составляет 1,62.

“Oil of vitriol” redirects here. For sweet oil of vitriol, see Diethyl ether.

“Sulphuric acid” redirects here. For the novel by Amélie Nothomb, see Sulphuric Acid (novel).

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sulfuric acid |

||

| Other names

Oil of vitriol |

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

|

| ChEBI |

|

|

| ChEMBL |

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.763 |

|

| EC Number |

|

|

| E number | E513 (acidity regulators, …) | |

|

Gmelin Reference |

2122 | |

| KEGG |

|

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

|

| UNII |

|

|

| UN number | 1830 | |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

|

InChI

|

||

|

SMILES

|

||

| Properties | ||

|

Chemical formula |

H2SO4 | |

| Molar mass | 98.079 g/mol | |

| Appearance | Colorless viscous liquid | |

| Odor | Odorless | |

| Density | 1.8302 g/cm3, liquid[1] | |

| Melting point | 10.31[1] °C (50.56 °F; 283.46 K) | |

| Boiling point | 337[1] °C (639 °F; 610 K) When sulfuric acid is above 300 °C (572 °F; 573 K), it gradually decomposes to SO3 + H2O | |

|

Solubility in water |

miscible, exothermic | |

| Vapor pressure | 0.001 mmHg (20 °C)[2] | |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = −2.8 pKa2 = 1.99 |

|

| Conjugate base | Bisulfate | |

| Viscosity | 26.7 cP (20 °C) | |

| Structure[3] | ||

|

Crystal structure |

monoclinic | |

|

Space group |

C2/c | |

|

Lattice constant |

a = 818.1(2) pm, b = 469.60(10) pm, c = 856.3(2) pm α = 90°, β = 111.39(3) pm°, γ = 90° |

|

|

Formula units (Z) |

4 | |

| Thermochemistry | ||

|

Std molar |

157 J/(mol·K)[4] | |

|

Std enthalpy of |

−814 kJ/mol[4] | |

| Hazards | ||

| GHS labelling: | ||

|

Pictograms |

|

|

|

Signal word |

Danger | |

|

Hazard statements |

H314 | |

|

Precautionary statements |

P260, P264, P280, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P321, P363, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3 0 2

|

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable | |

|

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

15 mg/m3 (IDLH), 1 mg/m3 (TWA), 2 mg/m3 (STEL) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | ||

|

LD50 (median dose) |

2140 mg/kg (rat, oral)[5] | |

|

LC50 (median concentration) |

[5] |

|

|

LCLo (lowest published) |

87 mg/m3 (guinea pig, 2.75 hr)[5] | |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | ||

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 1 mg/m3[2] | |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1 mg/m3[2] | |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

15 mg/m3[2] | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS | |

| Related compounds | ||

|

Related strong acids |

|

|

|

Related compounds |

|

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, and hydrogen, with the molecular formula H2SO4. It is a colorless, odorless, and viscous liquid that is miscible with water.[6]

Pure sulfuric acid does not occur naturally due to its strong affinity to water vapor; it is hygroscopic and readily absorbs water vapor from the air.[6] Concentrated sulfuric acid is highly corrosive towards other materials, from rocks to metals, since it is an oxidant with powerful dehydrating properties. Phosphorus pentoxide is a notable exception in that it is not dehydrated by sulfuric acid but, to the contrary, dehydrates sulfuric acid to sulfur trioxide. Upon addition of sulfuric acid to water, a considerable amount of heat is released; thus, the reverse procedure of adding water to the acid should not be performed since the heat released may boil the solution, spraying droplets of hot acid during the process. Upon contact with body tissue, sulfuric acid can cause severe acidic chemical burns and even secondary thermal burns due to dehydration.[7][8] Dilute sulfuric acid is substantially less hazardous without the oxidative and dehydrating properties; however, it should still be handled with care for its acidity.

Sulfuric acid is a very important commodity chemical; a country’s sulfuric acid production is a good indicator of its industrial strength.[9][non-primary source needed] It is widely produced with different methods, such as contact process, wet sulfuric acid process, lead chamber process, and some other methods.[which?][10] Sulfuric acid is also a key substance in the chemical industry. It is most commonly used in fertilizer manufacture[11] but is also important in mineral processing, oil refining, wastewater processing, and chemical synthesis. It has a wide range of end applications, including in domestic acidic drain cleaners,[12] as an electrolyte in lead-acid batteries, in dehydrating a compound, and in various cleaning agents.

Sulfuric acid can be obtained by dissolving sulfur trioxide in water.

Physical properties[edit]

Grades of sulfuric acid[edit]

Although nearly 100% sulfuric acid solutions can be made, the subsequent loss of SO3 at the boiling point brings the concentration to 98.3% acid. The 98.3% grade is more stable in storage, and is the usual form of what is described as “concentrated sulfuric acid”. Other concentrations are used for different purposes. Some common concentrations are:[13][14]

| Mass fraction H2SO4 |

Density (kg/L) |

Concentration (mol/L) |

Common name |

|---|---|---|---|

| <29% | 1.00-1.25 | <4.2 | diluted sulfuric acid |

| 29–32% | 1.25–1.28 | 4.2–5.0 | battery acid (used in lead–acid batteries) |

| 62–70% | 1.52–1.60 | 9.6–11.5 | chamber acid fertilizer acid |

| 78–80% | 1.70–1.73 | 13.5–14.0 | tower acid Glover acid |

| 93.2% | 1.83 | 17.4 | 66 °Bé (“66-degree Baumé”) acid |

| 98.3% | 1.84 | 18.4 | concentrated sulfuric acid |

“Chamber acid” and “tower acid” were the two concentrations of sulfuric acid produced by the lead chamber process, chamber acid being the acid produced in the lead chamber itself (<70% to avoid contamination with nitrosylsulfuric acid) and tower acid being the acid recovered from the bottom of the Glover tower.[13][14] They are now obsolete as commercial concentrations of sulfuric acid, although they may be prepared in the laboratory from concentrated sulfuric acid if needed. In particular, “10 M” sulfuric acid (the modern equivalent of chamber acid, used in many titrations), is prepared by slowly adding 98% sulfuric acid to an equal volume of water, with good stirring: the temperature of the mixture can rise to 80 °C (176 °F) or higher.[14]

Pure sulfuric acid[edit]

Pure sulfuric acid contains not only H2SO4 molecules, but is actually an equilibrium of many other chemical species, as it is shown in the table below.

| Species | mMol/kg |

|---|---|

| HSO−4 | 15.0 |

| H3SO+4 | 11.3 |

| H3O+ | 8.0 |

| HS2O−7 | 4.4 |

| H2S2O7 | 3.6 |

| H2O | 0.1 |

Pure sulfuric acid is a colorless oily liquid, and has a vapor pressure of <0.001 mmHg at 25 °C and 1 mmHg at 145.8 °C,[16] and 98% sulfuric acid has a <1 mmHg vapor pressure at 40 °C.[17]

In the solid state, sulfuric acid is a molecular solid that forms monoclinic crystals with nearly trigonal lattice parameters. The structure consists of layers parallel to the (010) plane, in which each molecule is connected by hydrogen bonds to two others.[3] Hydrates H2SO4·nH2O are known for n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 6.5, and 8, although most intermediate hydrates are stable against disproportionation.[18]

Polarity and conductivity[edit]

Anhydrous H2SO4 is a very polar liquid, having a dielectric constant of around 100. It has a high electrical conductivity, caused by dissociation through protonating itself, a process known as autoprotolysis.[15]

The equilibrium constant for autoprotolysis is[15]

The comparable equilibrium constant for water, Kw is 10−14, a factor of 1010 (10 billion) smaller.

In spite of the viscosity of the acid, the effective conductivities of the H3SO+4 and HSO−4 ions are high due to an intramolecular proton-switch mechanism (analogous to the Grotthuss mechanism in water), making sulfuric acid a good conductor of electricity. It is also an excellent solvent for many reactions.

Chemical properties[edit]

Reaction with water and dehydrating property[edit]

An experiment that demonstrates the dehydration properties of concentrated sulfuric acid. When concentrated sulfuric acid comes into contact with sucrose, slow carbonification of the sucrose takes place. The reaction is accompanied by the evolution of gaseous products that contribute to the formation of the foamy carbon pillar that rises above the beaker.

Drops of concentrated sulfuric acid rapidly decompose a piece of cotton towel by dehydration.

Because the hydration reaction of sulfuric acid is highly exothermic, dilution should be performed by adding the acid to the water rather than the water to the acid, to avoid acid splashing.[19] Because the reaction favors the rapid protonation of water, addition of acid to the water ensures that the acid is the limiting reagent. This reaction may be thought of as the formation of hydronium ions:

[20]

HSO−4 is the bisulfate anion and SO2−4 is the sulfate anion. Ka1 and Ka2 are the acid dissociation constants.

Concentrated sulfuric acid has a powerful dehydrating property, removing water (H2O) from other chemical compounds such as table sugar (sucrose) and other carbohydrates, to produce carbon, steam, and heat. Dehydration of table sugar (sucrose) is a common laboratory demonstration.[21] The sugar darkens as carbon is formed, and a rigid column of black, porous carbon called a carbon snake may emerge[22] as shown in the figure.

Similarly, mixing starch into concentrated sulfuric acid gives elemental carbon and water that is absorbed by the sulfuric acid, slightly diluting it. The effect of this can be seen when concentrated sulfuric acid is spilled on paper, which is composed of cellulose; the cellulose reacts to give a burnt appearance in which the carbon appears much like soot that results from fire.

Although less dramatic, the action of the acid on cotton, even in diluted form, destroys the fabric.

The reaction with copper(II) sulfate can also demonstrate the dehydration property of sulfuric acid. The blue crystals change into white powder as water is removed:

Acid-base properties[edit]

As an acid, sulfuric acid reacts with most bases to give the corresponding sulfate. For example, the blue copper salt copper(II) sulfate, commonly used for electroplating and as a fungicide, is prepared by the reaction of copper(II) oxide with sulfuric acid:

- CuO(s) + H2SO4(aq) → CuSO4(aq) + H2O(l)

Sulfuric acid can also be used to displace weaker acids from their salts. Reaction with sodium acetate, for example, displaces acetic acid, CH3COOH, and forms sodium bisulfate:

- H2SO4 + CH3COONa → NaHSO4 + CH3COOH

Similarly, reacting sulfuric acid with potassium nitrate can be used to produce nitric acid and a precipitate of potassium bisulfate. When combined with nitric acid, sulfuric acid acts both as an acid and a dehydrating agent, forming the nitronium ion NO+2, which is important in nitration reactions involving electrophilic aromatic substitution. This type of reaction, where protonation occurs on an oxygen atom, is important in many organic chemistry reactions, such as Fischer esterification and dehydration of alcohols.

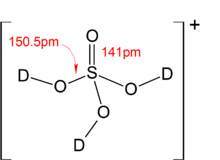

Solid state structure of the

[D3SO4]+ ion present in

[D3SO4]+[SbF6]−, synthesized by using DF in place of HF. (see text)

When allowed to react with superacids, sulfuric acid can act as a base and can be protonated, forming the [H3SO4]+ ion. Salts of [H3SO4]+ have been prepared (e.g. trihydroxyoxosulfonium hexafluoroantimonate(V) [H3SO4]+[SbF6]−) using the following reaction in liquid HF:

- [(CH3)3SiO]2SO2 + 3 HF + SbF5 → [H3SO4]+[SbF6]− + 2 (CH3)3SiF

The above reaction is thermodynamically favored due to the high bond enthalpy of the Si–F bond in the side product. Protonation using simply fluoroantimonic acid, however, has met with failure, as pure sulfuric acid undergoes self-ionization to give [H3O]+ ions:

- 2 H2SO4 ⇌ [H3O]+ + [HS2O7]−

which prevents the conversion of H2SO4 to [H3SO4]+ by the HF/SbF5 system.[23]

Reactions with metals[edit]

Even dilute sulfuric acid reacts with many metals via a single displacement reaction, like other typical acids, producing hydrogen gas and salts (the metal sulfate). It attacks reactive metals (metals at positions above copper in the reactivity series) such as iron, aluminium, zinc, manganese, magnesium, and nickel.

- Fe + H2SO4 → H2 + FeSO4

Concentrated sulfuric acid can serve as an oxidizing agent, releasing sulfur dioxide:[7]

- Cu + 2 H2SO4 → SO2 + 2 H2O + SO2−4 + Cu2+

Lead and tungsten, however, are resistant to sulfuric acid.

Reactions with carbon and sulfur[edit]

Hot concentrated sulfuric acid oxidizes carbon[24] (as bituminous coal) and sulfur:

- C + 2 H2SO4 → CO2 + 2 SO2 + 2 H2O

- S + 2 H2SO4 → 3 SO2 + 2 H2O

Reaction with sodium chloride[edit]

It reacts with sodium chloride, and gives hydrogen chloride gas and sodium bisulfate:

- NaCl + H2SO4 → NaHSO4 + HCl

Electrophilic aromatic substitution[edit]

Benzene undergoes electrophilic aromatic substitution with sulfuric acid to give the corresponding sulfonic acids:[25]

Occurrence[edit]

Pure sulfuric acid is not encountered naturally on Earth in anhydrous form, due to its great affinity for water. Dilute sulfuric acid is a constituent of acid rain, which is formed by atmospheric oxidation of sulfur dioxide in the presence of water – i.e. oxidation of sulfurous acid. When sulfur-containing fuels such as coal or oil are burned, sulfur dioxide is the main byproduct (besides the chief products carbon oxides and water).

Sulfuric acid is formed naturally by the oxidation of sulfide minerals, such as iron sulfide. The resulting water can be highly acidic and is called acid mine drainage (AMD) or acid rock drainage (ARD). This acidic water is capable of dissolving metals present in sulfide ores, which results in brightly colored, toxic solutions. The oxidation of pyrite (iron sulfide) by molecular oxygen produces iron(II), or Fe2+:

- 2 FeS2(s) + 7 O2 + 2 H2O → 2 Fe2+ + 4 SO2−4 + 4 H+

The Fe2+ can be further oxidized to Fe3+:

- 4 Fe2+ + O2 + 4 H+ → 4 Fe3+ + 2 H2O

The Fe3+ produced can be precipitated as the hydroxide or hydrous iron oxide:

- Fe3+ + 3 H2O → Fe(OH)3↓ + 3 H+

The iron(III) ion (“ferric iron”) can also oxidize pyrite:

- FeS2(s) + 14 Fe3+ + 8 H2O → 15 Fe2+ + 2 SO2−4 + 16 H+

When iron(III) oxidation of pyrite occurs, the process can become rapid. pH values below zero have been measured in ARD produced by this process.

ARD can also produce sulfuric acid at a slower rate, so that the acid neutralizing capacity (ANC) of the aquifer can neutralize the produced acid. In such cases, the total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration of the water can be increased from the dissolution of minerals from the acid-neutralization reaction with the minerals.

Sulfuric acid is used as a defense by certain marine species, for example, the phaeophyte alga Desmarestia munda (order Desmarestiales) concentrates sulfuric acid in cell vacuoles.[26]

Stratospheric aerosol[edit]

In the stratosphere, the atmosphere’s second layer that is generally between 10 and 50 km above Earth’s surface, sulfuric acid is formed by the oxidation of volcanic sulfur dioxide by the hydroxyl radical:[27]

- SO2 + HO• → HSO3

- HSO3 + O2 → SO3 + HO2

- SO3 + H2O → H2SO4

Because sulfuric acid reaches supersaturation in the stratosphere, it can nucleate aerosol particles and provide a surface for aerosol growth via condensation and coagulation with other water-sulfuric acid aerosols. This results in the stratospheric aerosol layer.[27]

[edit]

The permanent Venusian clouds produce a concentrated acid rain, as the clouds in the atmosphere of Earth produce water rain.[28] Jupiter’s moon Europa is also thought to have an atmosphere containing sulfuric acid hydrates.[29]

Manufacturing[edit]

Sulfuric acid is produced from sulfur, oxygen and water via the conventional contact process (DCDA) or the wet sulfuric acid process (WSA).

Contact process[edit]

In the first step, sulfur is burned to produce sulfur dioxide.

- S(s) + O2 → SO2

The sulfur dioxide is oxidized to sulfur trioxide by oxygen in the presence of a vanadium(V) oxide catalyst. This reaction is reversible and the formation of the sulfur trioxide is exothermic.

- 2 SO2 + O2 ⇌ 2 SO3

The sulfur trioxide is absorbed into 97–98% H2SO4 to form oleum (H2S2O7), also known as fuming sulfuric acid or pyrosulphuric acid. The oleum is then diluted with water to form concentrated sulfuric acid.

- H2SO4 + SO3 → H2S2O7

- H2S2O7 + H2O → 2 H2SO4

Directly dissolving SO3 in water, called the “wet sulfuric acid process”, is rarely practiced because the reaction is extremely exothermic, resulting in a hot aerosol of sulfuric acid that requires condensation and separation.

Wet sulfuric acid process[edit]

In the first step, sulfur is burned to produce sulfur dioxide:

- S + O2 → SO2 (−297 kJ/mol)

or, alternatively, hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas is incinerated to SO2 gas:

- 2 H2S + 3 O2 → 2 H2O + 2 SO2 (−1036 kJ/mol)

The sulfur dioxide then oxidized to sulfur trioxide using oxygen with vanadium(V) oxide as catalyst.

- 2 SO2 + O2 ⇌ 2 SO3 (−198 kJ/mol) (reaction is reversible)

The sulfur trioxide is hydrated into sulfuric acid H2SO4:

- SO3 + H2O → H2SO4(g) (−101 kJ/mol)

The last step is the condensation of the sulfuric acid to liquid 97–98% H2SO4:

- H2SO4(g) → H2SO4(l) (−69 kJ/mol)

Other methods[edit]

A method that is the less well-known is the metabisulfite method, in which metabisulfite is placed at the bottom of a beaker and 12.6 molar concentration hydrochloric acid is added. The resulting gas is bubbled through nitric acid, which will release brown/red vapors of nitrogen dioxide as the reaction proceeds. The completion of the reaction is indicated by the ceasing of the fumes. This method does not produce an inseparable mist, which is quite convenient.

- 3 SO2 + 2 HNO3 + 2 H2O → 3 H2SO4 + 2 NO

Burning sulfur together with saltpeter (potassium nitrate, KNO3), in the presence of steam, has been used historically. As saltpeter decomposes, it oxidizes the sulfur to SO3, which combines with water to produce sulfuric acid.

Alternatively, dissolving sulfur dioxide in an aqueous solution of an oxidizing metal salt such as copper(II) or iron(III) chloride:

- 2 FeCl3 + 2 H2O + SO2 → 2 FeCl2 + H2SO4 + 2 HCl

- 2 CuCl2 + 2 H2O + SO2 → 2 CuCl + H2SO4 + 2 HCl

Two less well-known laboratory methods of producing sulfuric acid, albeit in dilute form and requiring some extra effort in purification. A solution of copper(II) sulfate can be electrolyzed with a copper cathode and platinum/graphite anode to give spongy copper at cathode and evolution of oxygen gas at the anode, the solution of dilute sulfuric acid indicates completion of the reaction when it turns from blue to clear (production of hydrogen at cathode is another sign):

- 2 CuSO4 + 2 H2O → 2 Cu + 2 H2SO4 + O2

More costly, dangerous, and troublesome yet novel is the electrobromine method, which employs a mixture of sulfur, water, and hydrobromic acid as the electrolytic solution. The sulfur is pushed to bottom of container under the acid solution. Then the copper cathode and platinum/graphite anode are used with the cathode near the surface and the anode is positioned at the bottom of the electrolyte to apply the current. This may take longer and emits toxic bromine/sulfur bromide vapors, but the reactant acid is recyclable. Overall, only the sulfur and water are converted to sulfuric acid and hydrogen (omitting losses of acid as vapors):

- 2 HBr → H2 + Br2 (electrolysis of aqueous hydrogen bromide)

- Br2 + Br− ↔ Br−3 (initial tribromide production, eventually reverses as Br− depletes)

- 2 S + Br2 → S2Br2 (bromine reacts with sulfur to form disulfur dibromide)

- S2Br2 + 8 H2O + 5 Br2 → 2 H2SO4 + 12 HBr (oxidation and hydration of disulfur dibromide)

Prior to 1900, most sulfuric acid was manufactured by the lead chamber process.[30] As late as 1940, up to 50% of sulfuric acid manufactured in the United States was produced by chamber process plants.

In the early to mid 19th century “vitriol” plants existed, among other places, in Prestonpans in Scotland, Shropshire and the Lagan Valley in County Antrim Ireland, where it was used as a bleach for linen. Early bleaching of linen was done using lactic acid from sour milk but this was a slow process and the use of vitriol sped up the bleaching process.[31]

Uses[edit]

Sulfuric acid production in 2000

Sulfuric acid is a very important commodity chemical, and indeed, a nation’s sulfuric acid production is a good indicator of its industrial strength.[9] World production in the year 2004 was about 180 million tonnes, with the following geographic distribution: Asia 35%, North America (including Mexico) 24%, Africa 11%, Western Europe 10%, Eastern Europe and Russia 10%, Australia and Oceania 7%, South America 7%.[32] Most of this amount (≈60%) is consumed for fertilizers, particularly superphosphates, ammonium phosphate and ammonium sulfates. About 20% is used in chemical industry for production of detergents, synthetic resins, dyestuffs, pharmaceuticals, petroleum catalysts, insecticides and antifreeze, as well as in various processes such as oil well acidicizing, aluminium reduction, paper sizing, and water treatment. About 6% of uses are related to pigments and include paints, enamels, printing inks, coated fabrics and paper, while the rest is dispersed into a multitude of applications such as production of explosives, cellophane, acetate and viscose textiles, lubricants, non-ferrous metals, and batteries.[33]

Industrial production of chemicals[edit]

The major use for sulfuric acid is in the “wet method” for the production of phosphoric acid, used for manufacture of phosphate fertilizers. In this method, phosphate rock is used, and more than 100 million tonnes are processed annually. This raw material is shown below as fluorapatite, though the exact composition may vary. This is treated with 93% sulfuric acid to produce calcium sulfate, hydrogen fluoride (HF) and phosphoric acid. The HF is removed as hydrofluoric acid. The overall process can be represented as:

Ammonium sulfate, an important nitrogen fertilizer, is most commonly produced as a byproduct from coking plants supplying the iron and steel making plants. Reacting the ammonia produced in the thermal decomposition of coal with waste sulfuric acid allows the ammonia to be crystallized out as a salt (often brown because of iron contamination) and sold into the agro-chemicals industry.

Another important use for sulfuric acid is for the manufacture of aluminium sulfate, also known as paper maker’s alum. This can react with small amounts of soap on paper pulp fibers to give gelatinous aluminium carboxylates, which help to coagulate the pulp fibers into a hard paper surface. It is also used for making aluminium hydroxide, which is used at water treatment plants to filter out impurities, as well as to improve the taste of the water. Aluminium sulfate is made by reacting bauxite with sulfuric acid:

- 2 AlO(OH) + 3 H2SO4 → Al2(SO4)3 + 4 H2O

Sulfuric acid is also important in the manufacture of dyestuffs solutions.

Sulfur–iodine cycle[edit]

The sulfur–iodine cycle is a series of thermo-chemical processes possibly usable to produce hydrogen from water. It consists of three chemical reactions whose net reactant is water and whose net products are hydrogen and oxygen.

-

2 I2 + 2 SO2 + 4 H2O → 4 HI + 2 H2SO4 (120 °C, Bunsen reaction) 2 H2SO4 → 2 SO2 + 2 H2O + O2 (830 °C) 4 HI → 2 I2 + 2 H2 (320 °C)

The compounds of sulfur and iodine are recovered and reused, hence the consideration of the process as a cycle. This process is endothermic and must occur at high temperatures, so energy in the form of heat has to be supplied.

The sulfur–iodine cycle has been proposed as a way to supply hydrogen for a hydrogen-based economy. It is an alternative to electrolysis, and does not require hydrocarbons like current methods of steam reforming. But note that all of the available energy in the hydrogen so produced is supplied by the heat used to make it.

The sulfur–iodine cycle is currently being researched as a feasible method of obtaining hydrogen, but the concentrated, corrosive acid at high temperatures poses currently insurmountable safety hazards if the process were built on a large scale.[34][35]

Hybrid sulfur cycle[edit]

The hybrid sulfur cycle (HyS) is a two-step water splitting process intended to be used for hydrogen production. Based on sulfur oxidation and reduction, it is classified as a hybrid thermochemical cycle because it uses an electrochemical (instead of a thermochemical) reaction for one of the two steps. The remaining thermochemical step is shared with the sulfur-iodine cycle.

Industrial cleaning agent[edit]

Sulfuric acid is used in large quantities by the iron and steelmaking industry to remove oxidation, rust, and scaling from rolled sheet and billets prior to sale to the automobile and major appliances industry.[citation needed] Used acid is often recycled using a spent acid regeneration (SAR) plant. These plants combust spent acid[clarification needed] with natural gas, refinery gas, fuel oil or other fuel sources. This combustion process produces gaseous sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur trioxide (SO3) which are then used to manufacture “new” sulfuric acid. SAR plants are common additions to metal smelting plants, oil refineries, and other industries where sulfuric acid is consumed in bulk, as operating a SAR plant is much cheaper than the recurring costs of spent acid disposal and new acid purchases.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) can be added to sulfuric acid to produce piranha solution, a powerful but very toxic cleaning solution with which substrate surfaces can be cleaned. Piranha solution is typically used in the microelectronics industry, and also in laboratory settings to clean glassware.

Catalyst[edit]

Sulfuric acid is used for a variety of other purposes in the chemical industry. For example, it is the usual acid catalyst for the conversion of cyclohexanone oxime to caprolactam, used for making nylon. It is used for making hydrochloric acid from salt via the Mannheim process. Much H2SO4 is used in petroleum refining, for example as a catalyst for the reaction of isobutane with isobutylene to give isooctane, a compound that raises the octane rating of gasoline (petrol). Sulfuric acid is also often used as a dehydrating or oxidizing agent in industrial reactions, such as the dehydration of various sugars to form solid carbon.

Electrolyte[edit]

Acidic drain cleaners usually contain sulfuric acid at a high concentration which turns a piece of pH paper red and chars it instantly, demonstrating both the strong acidic nature and dehydrating property.

Sulfuric acid acts as the electrolyte in lead–acid batteries (lead-acid accumulator):

At anode:

- Pb + SO2−4 ⇌ PbSO4 + 2 e−

At cathode:

- PbO2 + 4 H+ + SO2−4 + 2 e− ⇌ PbSO4 + 2 H2O

An acidic drain cleaner can be used to dissolve grease, hair and even tissue paper inside water pipes.

Overall:

- Pb + PbO2 + 4 H+ + 2 SO2−4 ⇌ 2 PbSO4 + 2 H2O

Domestic uses[edit]

Sulfuric acid at high concentrations is frequently the major ingredient in acidic drain cleaners[12] which are used to remove grease, hair, tissue paper, etc. Similar to their alkaline versions, such drain openers can dissolve fats and proteins via hydrolysis. Moreover, as concentrated sulfuric acid has a strong dehydrating property, it can remove tissue paper via dehydrating process as well. Since the acid may react with water vigorously, such acidic drain openers should be added slowly into the pipe to be cleaned.

History[edit]

The study of vitriols (hydrated sulfates of various metals forming glassy minerals from which sulfuric acid can be derived) began in ancient times. Sumerians had a list of types of vitriol that they classified according to the substances’ color. Some of the earliest discussions on the origin and properties of vitriol is in the works of the Greek physician Dioscorides (first century AD) and the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD). Galen also discussed its medical use. Metallurgical uses for vitriolic substances were recorded in the Hellenistic alchemical works of Zosimos of Panopolis, in the treatise Phisica et Mystica, and the Leyden papyrus X.[36]

Medieval Islamic chemists like the authors writing under the name of Jabir ibn Hayyan (died c. 806 – c. 816 AD, known in Latin as Geber), Abu Bakr al-Razi (865 – 925 AD, known in Latin as Rhazes), Ibn Sina (980 – 1037 AD, known in Latin as Avicenna), and Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Watwat (1234 – 1318 AD) included vitriol in their mineral classification lists.[37] The Jabirian authors and Abu Bakr al-Razi also experimented extensively with the distillation of various substances, including vitriols.[38] In one recipe recorded in his Kitāb al-Asrār (‘Book of Secrets’), Abu Bakr al-Razi may have created sulfuric acid without being aware of it:[39]

Take white (Yemeni) alum, dissolve it and purify it by filtration. Then distil (green ?) vitriol with copper-green (the acetate), and mix (the distillate) with the filtered solution of the purified alum, afterwards let it solidify (or crystallise) in the glass beaker. You will get the best qalqadis (white alum) that may be had.[40]

In an anonymous Latin work variously attributed to Aristotle (under the title Liber Aristotilis, ‘Book of Aristotle’),[41] to Abu Bakr al-Razi (under the title Lumen luminum magnum, ‘Great Light of Lights’), or to Ibn Sina,[42] the author speaks of an ‘oil’ (oleum) obtained through the distillation of iron(II) sulfate (green vitriol), which was likely ‘oil of vitriol’ or sulfuric acid.[43] The work refers multiple times to Jabir ibn Hayyan’s Book of Seventy (Liber de septuaginta), one of the few Arabic Jabir works that were translated into Latin.[44] The author of the version attributed to al-Razi also refers to the Liber de septuaginta as his own work, showing that he erroneously believed the Liber de septuaginta to be a work by al-Razi.[45] There are several indications that the anonymous work was an original composition in Latin,[46] although according to one manuscript it was translated by a certain Raymond of Marseilles, meaning that it may also have been a translation from the Arabic.[47]

According to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, three recipes for sulfuric acid occur in an anonymous Karshuni manuscript containing a compilation taken from several authors and dating from before c. 1100 AD.[48] One of them runs as follows:

The water of vitriol and sulphur which is used to irrigate the drugs: yellow vitriol three parts, yellow sulphur one part, grind them and distil them in the manner of rose-water.[49]

A recipe for the preparation of sulfuric acid is mentioned in Risālat Jaʿfar al-Sādiq fī ʿilm al-ṣanʿa, an Arabic treatise falsely attributed to the Shi’i Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq (died 765). Julius Ruska dated this treatise to the 13th century, but according to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan it likely dates from an earlier period:[50]

Then distil green vitriol in a cucurbit and alembic, using medium fire; take what you obtain from the distillate, and you will find it clear with a greenish tint.[51]

Sulfuric acid was called ‘oil of vitriol’ by medieval European alchemists because it was prepared by roasting iron(II) sulfate or green vitriol in an iron retort. The first allusions to it in works that are definitely European in origin appear in the thirteenth century AD, as for example in the works of Vincent of Beauvais, in the Compositum de Compositis ascribed to Albertus Magnus, and in pseudo-Geber’s Summa perfectionis.[52]

In the seventeenth century, the German-Dutch chemist Johann Glauber prepared sulfuric acid by burning sulfur together with saltpeter (potassium nitrate, KNO3), in the presence of steam. As saltpeter decomposes, it oxidizes the sulfur to SO3, which combines with water to produce sulfuric acid. In 1736, Joshua Ward, a London pharmacist, used this method to begin the first large-scale production of sulfuric acid.

In 1746 in Birmingham, John Roebuck adapted this method to produce sulfuric acid in lead-lined chambers, which were stronger, less expensive, and could be made larger than the previously used glass containers. This process allowed the effective industrialization of sulfuric acid production. After several refinements, this method, called the lead chamber process or “chamber process”, remained the standard for sulfuric acid production for almost two centuries.[4]

Sulfuric acid created by John Roebuck’s process approached a 65% concentration. Later refinements to the lead chamber process by French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and British chemist John Glover improved concentration to 78%. However, the manufacture of some dyes and other chemical processes require a more concentrated product. Throughout the 18th century, this could only be made by dry distilling minerals in a technique similar to the original alchemical processes. Pyrite (iron disulfide, FeS2) was heated in air to yield iron(II) sulfate, FeSO4, which was oxidized by further heating in air to form iron(III) sulfate, Fe2(SO4)3, which, when heated to 480 °C, decomposed to iron(III) oxide and sulfur trioxide, which could be passed through water to yield sulfuric acid in any concentration. However, the expense of this process prevented the large-scale use of concentrated sulfuric acid.[4]

In 1831, British vinegar merchant Peregrine Phillips patented the contact process, which was a far more economical process for producing sulfur trioxide and concentrated sulfuric acid. Today, nearly all of the world’s sulfuric acid is produced using this method.[53]

Safety[edit]

Laboratory hazards[edit]

Drops of 98% sulfuric acid char a piece of tissue paper instantly. Carbon is left after the dehydration reaction staining the paper black.

Nitrile glove exposed to drops of 98% sulfuric acid for 10 minutes

Superficial chemical burn caused by two 98% sulfuric acid splashes (forearm skin)

Sulfuric acid is capable of causing very severe burns, especially when it is at high concentrations. In common with other corrosive acids and alkali, it readily decomposes proteins and lipids through amide and ester hydrolysis upon contact with living tissues, such as skin and flesh. In addition, it exhibits a strong dehydrating property on carbohydrates, liberating extra heat and causing secondary thermal burns.[7][8] Accordingly, it rapidly attacks the cornea and can induce permanent blindness if splashed onto eyes. If ingested, it damages internal organs irreversibly and may even be fatal.[6] Protective equipment should hence always be used when handling it. Moreover, its strong oxidizing property makes it highly corrosive to many metals and may extend its destruction on other materials.[7] Because of such reasons, damage posed by sulfuric acid is potentially more severe than that by other comparable strong acids, such as hydrochloric acid and nitric acid.

Sulfuric acid must be stored carefully in containers made of nonreactive material (such as glass). Solutions equal to or stronger than 1.5 M are labeled “CORROSIVE”, while solutions greater than 0.5 M but less than 1.5 M are labeled “IRRITANT”. However, even the normal laboratory “dilute” grade (approximately 1 M, 10%) will char paper if left in contact for a sufficient time.

The standard first aid treatment for acid spills on the skin is, as for other corrosive agents, irrigation with large quantities of water. Washing is continued for at least ten to fifteen minutes to cool the tissue surrounding the acid burn and to prevent secondary damage. Contaminated clothing is removed immediately and the underlying skin washed thoroughly.

Dilution hazards[edit]

Preparation of the diluted acid can be dangerous due to the heat released in the dilution process. To avoid splattering, the concentrated acid is usually added to water and not the other way around. A saying used to remember this is “Do like you oughta, add the acid to the water”.[54][better source needed] Water has a higher heat capacity than the acid, and so a vessel of cold water will absorb heat as acid is added.

| Physical property | H2SO4 | Water | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.84 | 1.0 | kg/L |

| Volumetric heat capacity | 2.54 | 4.18 | kJ/L |

| Boiling point | 337 | 100 | °C |

Also, because the acid is denser than water, it sinks to the bottom. Heat is generated at the interface between acid and water, which is at the bottom of the vessel. Acid will not boil, because of its higher boiling point. Warm water near the interface rises due to convection, which cools the interface, and prevents boiling of either acid or water.

In contrast, addition of water to concentrated sulfuric acid results in a thin layer of water on top of the acid. Heat generated in this thin layer of water can boil, leading to the dispersal of a sulfuric acid aerosol or worse, an explosion.

Preparation of solutions greater than 6 M (35%) in concentration is dangerous, unless the acid is added slowly enough to allow the mixture sufficient time to cool. Otherwise, the heat produced may be sufficient to boil the mixture. Efficient mechanical stirring and external cooling (such as an ice bath) are essential.

Reaction rates double for about every 10-degree Celsius increase in temperature.[55] Therefore, the reaction will become more violent as dilution proceeds, unless the mixture is given time to cool. Adding acid to warm water will cause a violent reaction.

On a laboratory scale, sulfuric acid can be diluted by pouring concentrated acid onto crushed ice made from de-ionized water. The ice melts in an endothermic process while dissolving the acid. The amount of heat needed to melt the ice in this process is greater than the amount of heat evolved by dissolving the acid so the solution remains cold. After all the ice has melted, further dilution can take place using water.

Industrial hazards[edit]

Sulfuric acid is non-flammable.

The main occupational risks posed by this acid are skin contact leading to burns (see above) and the inhalation of aerosols. Exposure to aerosols at high concentrations leads to immediate and severe irritation of the eyes, respiratory tract and mucous membranes: this ceases rapidly after exposure, although there is a risk of subsequent pulmonary edema if tissue damage has been more severe. At lower concentrations, the most commonly reported symptom of chronic exposure to sulfuric acid aerosols is erosion of the teeth, found in virtually all studies: indications of possible chronic damage to the respiratory tract are inconclusive as of 1997. Repeated occupational exposure to sulfuric acid mists may increase the chance of lung cancer by up to 64 percent.[56] In the United States, the permissible exposure limit (PEL) for sulfuric acid is fixed at 1 mg/m3: limits in other countries are similar. There have been reports of sulfuric acid ingestion leading to vitamin B12 deficiency with subacute combined degeneration. The spinal cord is most often affected in such cases, but the optic nerves may show demyelination, loss of axons and gliosis.

Legal restrictions[edit]

International commerce of sulfuric acid is controlled under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988, which lists sulfuric acid under Table II of the convention as a chemical frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances.[57]

See also[edit]

- Aqua regia

- Diethyl ether – also known as “sweet oil of vitriol”

- Piranha solution

- Sulfur oxoacid

- Sulfuric acid poisoning

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Haynes, William M. (2014). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (95 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 4–92. ISBN 9781482208689. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. “#0577”. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b Kemnitz, E.; Werner, C.; Trojanov, S. (15 November 1996). “Reinvestigation of Crystalline Sulfuric Acid and Oxonium Hydrogensulfate”. Acta Crystallographica Section C Crystal Structure Communications. 52 (11): 2665–2668. doi:10.1107/S0108270196006749.

- ^ a b c d Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b c “Sulfuric acid”. Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c “Sulfuric acid safety data sheet” (PDF). arkema-inc.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2012.

Clear to turbid oily odorless liquid, colorless to slightly yellow.

- ^ a b c d “Sulfuric acid – uses”. dynamicscience.com.au. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013.

- ^ a b “BASF Chemical Emergency Medical Guidelines – Sulfuric acid (H2SO4)” (PDF). BASF Chemical Company. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ a b Chenier, Philip J. (1987). Survey of Industrial Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 45–57. ISBN 978-0-471-01077-7.

- ^ Hermann Müller “Sulfuric Acid and Sulfur Trioxide” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. 2000 doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_635

- ^ “Sulfuric acid”.

- ^ a b “Sulphuric acid drain cleaner” (PDF). herchem.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ^ a b “Sulfuric Acid”. The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ a b c “Sulphuric acid”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1910–1911. pp. 65–69. Please note, no EB1911 wikilink is available to this article

- ^ a b c Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ “Sulfuric acid” (PDF). Determination of Noncancer Chronic Reference Exposure Levels Batch 2B December 2001. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2003. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ “Sulfuric Acid 98%” (PDF). rhodia.com. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Giauque, W. F.; Hornung, E. W.; Kunzler, J. E.; Rubin, T. R. (January 1960). “The Thermodynamic Properties of Aqueous Sulfuric Acid Solutions and Hydrates from 15 to 300K. 1”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 82 (1): 62–70. doi:10.1021/ja01486a014.

- ^ “Consortium of Local Education Authorities for the Provision of Science Equipment -STUDENT SAFETY SHEETS 22 Sulfuric(VI) acid” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2013.

- ^ “Ionization Constants of Inorganic Acids”. .chemistry.msu.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ Dolson, David A.; et al. (1995). “Carbohydrate Dehydration Demonstrations”. J. Chem. Educ. 72 (10): 927. Bibcode:1995JChEd..72..927D. doi:10.1021/ed072p927. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Helmenstine, Anne (18 February 2020). “Carbon Snake Demo (Sugar and Sulfuric Acid)”. Science Notes and Projects. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008). “Chapter 16: The group 16 elements”. Inorganic Chemistry, 3rd Edition. Pearson. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ Kinney, Corliss Robert; Grey, V. E. (1959). Reactions of a Bituminous Coal with Sulfuric Acid (PDF). Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2017.

- ^ Carey, F. A. “Reactions of Arenes. Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution”. On-Line Learning Center for Organic Chemistry. University of Calgary. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Pelletreau, K.; Muller-Parker, G. (2002). “Sulfuric acid in the phaeophyte alga Desmarestia munda deters feeding by the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis”. Marine Biology. 141 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00227-002-0809-6. S2CID 83697676.

- ^ a b Kremser, S.; Thomson, L.W. (2016). “Stratospheric aerosol—Observations, processes, and impact on climate” (PDF). Reviews of Geophysics. 54 (2): 278–335. Bibcode:2016RvGeo..54..278K. doi:10.1002/2015RG000511.

- ^ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A. (2006). “Chemical composition of Venus atmosphere and clouds: Some unsolved problems”. Planetary and Space Science. 54 (13–14): 1352–1359. Bibcode:2006P&SS…54.1352K. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.04.019.

- ^ Orlando, T. M.; McCord, T. B.; Grieves, G. A. (2005). “The chemical nature of Europa surface material and the relation to a subsurface ocean”. Icarus. 177 (2): 528–533. Bibcode:2005Icar..177..528O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.05.009.

- ^ Jones, Edward M. (1950). “Chamber Process Manufacture of Sulfuric Acid”. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 42 (11): 2208–2210. doi:10.1021/ie50491a016.

- ^ (Harm), Benninga, H. (1990). A history of lactic acid making: a chapter in the history of biotechnology. Dordrecht [Netherland]: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 9780792306252. OCLC 20852966.

- ^ Davenport, William George & King, Matthew J. (2006). Sulfuric acid manufacture: analysis, control and optimization. Elsevier. pp. 8, 13. ISBN 978-0-08-044428-4. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 653. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Ngo, Christian; Natowitz, Joseph (2016). Our Energy Future: Resources, Alternatives and the Environment. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 418–419. ISBN 9781119213369.

- ^ Pickard, Paul (25 May 2005). “2005 DOE Hydrogen Program Review: Sulfur-Iodine Thermochemical Cycle” (PDF). Sandia National Labs. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Karpenko, Vladimír; Norris, John A. (2002). “Vitriol in the History of Chemistry”. Chemické listy. 96 (12): 997–1005.

- ^ Karpenko & Norris 2002, pp. 999–1000.

- ^ Multhauf, Robert P. (1966). The Origins of Chemistry. London: Oldbourne. pp. 140-142.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Ping-Yü, Ho; Gwei-Djen, Lu; Sivin, Nathan (1980). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part IV, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08573-1. p. 195, note d. Stapleton, Henry E.; Azo, R.F.; Hidayat Husain, M. (1927). “Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century A.D.” Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. VIII (6): 317–418. OCLC 706947607. pp. 333 (on the Liber Bubacaris, cf. p. 369, note 3), 393. Quote from p. 393: “It is extremely curious to see how close ar-Rāzī came to the discovery of Sulphuric acid, without actually recognising the powerful solvent properties of the distillate of vitriols and alum. This is all the more surprising, as he fully realised the reactive powers of both Arsenic sulphide and Sal-ammoniac, the ‘Spirits’ with which he must have associated the distillate from alum”.

- ^ Needham et al. 1980, p. 195, note d.

- ^ Pattin, Adriaan (1972). “Un recueil alchimique: le manuscrit Firenze, Bibl. Riccardiana, L. III. 13. 119 – Description et documentation”. Bulletin de Philosophie Médiévale. 14: 89–107. doi:10.1484/J.BPM.3.143. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Moureau, Sébastien (2020). “Min al-kīmiyāʾ ad alchimiam. The Transmission of Alchemy from the Arab-Muslim World to the Latin West in the Middle Ages”. Micrologus. 28: 87–141. hdl:2078.1/211340. p. 114 (no. 20). Moureau mentions that the work also sometimes occurs anonymously. He gives its incipit as “cum de sublimiori atque precipuo rerum effectum …“. Some parts of it have been published by Ruska, Julius (1939). “Pseudepigraphe Rasis-Schriften”. Osiris. 7: 31–94. doi:10.1086/368502. S2CID 143373785. pp. 56–65.

- ^ Hoefer, Ferdinand (1866). Histoire de la chimie (2nd ed.). Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot. p. 341.

- ^ Ruska 1939, p. 58; Pattin 1972, p. 93; Halleux, Robert (1996). “The Reception of Arabic Alchemy in the West”. In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 3. London: Routledge. pp. 886–902. ISBN 9780415020633. p. 892. On the Latin Liber de septuaginta and the two other known Latin translations of Arabic Jabir works, see Moureau 2020, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Ruska 1939, p. 58.

- ^ Ruska 1939, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Halleux 1996, p. 892; Moureau 2020, p. 114. Moureau mentions that ‘Raymond of Marseilles’ may be the astronomer by that name (fl. 1141). Hoefer 1866, p. 343 still firmly believed that the work belonged to al-Razi, but this view has been abandoned ever since the studies done by Ruska 1939; cf. Moureau 2020, p. 117, quote “although many alchemical Latin texts are attributed to Rāzı̄, only one is, in the current state of research, known to be a translation of the famous physician and alchemist” (i.e., the Liber secretorum Bubacaris, a paraphrase of al-Razi’s Kitāb al-asrār); Ferrario, Gabriele (2009). “An Arabic Dictionary of Technical Alchemical Terms: MS Sprenger 1908 of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (fols. 3r–6r)”. Ambix. 56 (1): 36–48. doi:10.1179/174582309X405219. PMID 19831258. S2CID 41045827. p. 42, quote “A strong and yet to be refuted critique of this traditional attribution was proposed by Ruska […]”.

- ^ Al-Hassan 2001, pp. 60, 63. On the dating of this manuscript, see also Berthelot, Marcellin; Houdas, Octave V. (1893). La Chimie au Moyen Âge. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. vol. II, p. xvii.

- ^ Al-Hassan 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Williams, Alan (2012). The Sword and the Crucible: A History of the Metallurgy of European Swords Up to the 16th Century. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22783-5. p. 104. Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001). Science and Technology in Islam: Technology and applied sciences. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-103831-0. p. 60.

- ^ Al-Hassan 2001, p. 60.

- ^ Karpenko & Norris 2002, pp. 1002–1004.

- ^ Philip J. Chenier (1 April 2002). Survey of industrial chemistry. Springer. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-306-47246-6. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ Snyder, Lucy A. (4 November 2005). “Do like you oughta, add acid to water”. Lucy A. Snyder. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Pauling, L.C. (1988) General Chemistry, Dover Publications

- ^ Beaumont, JJ; Leveton, J; Knox, K; Bloom, T; McQuiston, T; Young, M; Goldsmith, R; Steenland, NK; Brown, DP; Halperin, WE (1987). “Lung cancer mortality in workers exposed to sulfuric acid mist and other acid mists”. J Natl Cancer Inst. 79 (5): 911–21. doi:10.1093/jnci/79.5.911. PMID 3479642.

- ^ “Annex to Form D (“Red List”), 11th Edition” (PDF). Vienna, Austria: International Narcotics Control Board. January 2007. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2008.

External links[edit]

- International Chemical Safety Card 0362

- Sulfuric acid at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- CDC – Sulfuric Acid – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- External Material Safety Data Sheet Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Calculators: surface tensions, and densities, molarities and molalities of aqueous sulfuric acid

- Sulfuric acid analysis – titration freeware

- Process flowsheet of sulfuric acid manufacturing by lead chamber process

Структурная формула

Истинная, эмпирическая, или брутто-формула: H2SO4

Химический состав Серной кислоты

| Символ | Элемент | Атомный вес | Число атомов | Процент массы |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | Водород | 1,008 | 2 | 2,1% |

| O | Кислород | 15,999 | 4 | 65,3% |

| S | Сера | 32,064 | 1 | 32,7% |

Молекулярная масса: 98,076

Серная кислота H2SO4 — сильная двухосновная кислота, отвечающая высшей степени окисления серы (+6). При обычных условиях концентрированная серная кислота — тяжёлая маслянистая жидкость без цвета и запаха, с кислым «медным» вкусом. В технике серной кислотой называют её смеси как с водой, так и с серным ангидридом SO3. Если молярное отношение SO3 : H2O меньше 1, то это водный раствор серной кислоты, если больше 1 — раствор SO3 в серной кислоте (олеум).

Название

В XVIII—XIX веках серу для пороха производили из серного колчедана (пирит) на купоросных заводах. Серную кислоту в то время называли «купоросным маслом» (как правило это был кристаллогидрат, по консистенции напоминающий масло), очевидно отсюда происхождение названия её солей (а точнее именно кристаллогидратов) — купоросы.

Получение серной кислоты

Промышленный (контактный) способ

В промышленности серную кислоту получают окислением диоксида серы (сернистый газ, образующийся в процессе сжигания серы или серного колчедана) до триоксида (серного ангидрида)с последующим взаимодействием SO3 с водой. Получаемую данным способом серную кислоту также называют контактной (концентрация 92-94 %).

Нитрозный (башенный) способ