Рассмотрим регулярные выражения в Python, начиная синтаксисом и заканчивая примерами использования.

Примечание Вы читаете улучшенную версию некогда выпущенной нами статьи.

- Основы регулярных выражений

- Регулярные выражения в Python

- Задачи

Основы регулярных выражений

Регулярками в Python называются шаблоны, которые используются для поиска соответствующего фрагмента текста и сопоставления символов.

Грубо говоря, у нас есть input-поле, в которое должен вводиться email-адрес. Но пока мы не зададим проверку валидности введённого email-адреса, в этой строке может оказаться совершенно любой набор символов, а нам это не нужно.

Чтобы выявить ошибку при вводе некорректного адреса электронной почты, можно использовать следующее регулярное выражение:

r'^[a-zA-Z0-9_.+-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9-]+(?:.[a-zA-Z0-9-]+)+$'По сути, наш шаблон — это набор символов, который проверяет строку на соответствие заданному правилу. Давайте разберёмся, как это работает.

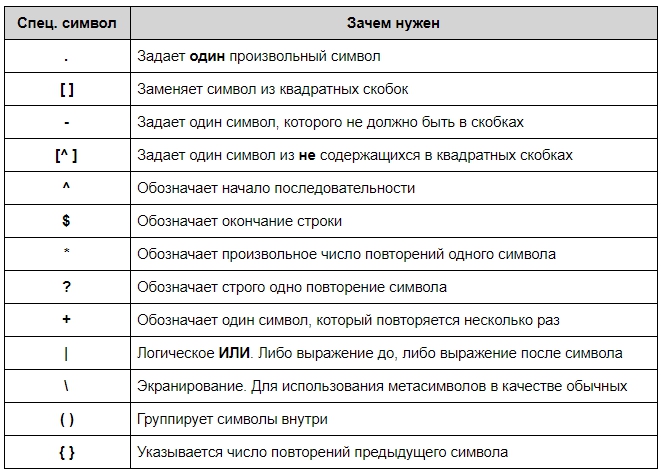

Синтаксис RegEx

Синтаксис у регулярок необычный. Символы могут быть как буквами или цифрами, так и метасимволами, которые задают шаблон строки:

Также есть дополнительные конструкции, которые позволяют сокращать регулярные выражения:

- d — соответствует любой одной цифре и заменяет собой выражение [0-9];

- D — исключает все цифры и заменяет [^0-9];

- w — заменяет любую цифру, букву, а также знак нижнего подчёркивания;

- W — любой символ кроме латиницы, цифр или нижнего подчёркивания;

- s — соответствует любому пробельному символу;

- S — описывает любой непробельный символ.

Для чего используются регулярные выражения

- для определения нужного формата, например телефонного номера или email-адреса;

- для разбивки строк на подстроки;

- для поиска, замены и извлечения символов;

- для быстрого выполнения нетривиальных операций.

Синтаксис таких выражений в основном стандартизирован, так что вам следует понять их лишь раз, чтобы использовать в любом языке программирования.

Примечание Не стоит забывать, что регулярные выражения не всегда оптимальны, и для простых операций часто достаточно встроенных в Python функций.

Хотите узнать больше? Обратите внимание на статью о регулярках для новичков.

В Python для работы с регулярками есть модуль re. Его нужно просто импортировать:

import reА вот наиболее популярные методы, которые предоставляет модуль:

re.match()re.search()re.findall()re.split()re.sub()re.compile()

Рассмотрим каждый из них подробнее.

re.match(pattern, string)

Этот метод ищет по заданному шаблону в начале строки. Например, если мы вызовем метод match() на строке «AV Analytics AV» с шаблоном «AV», то он завершится успешно. Но если мы будем искать «Analytics», то результат будет отрицательный:

import re

result = re.match(r'AV', 'AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result

Результат:

<_sre.SRE_Match object at 0x0000000009BE4370>

Искомая подстрока найдена. Чтобы вывести её содержимое, применим метод group() (мы используем «r» перед строкой шаблона, чтобы показать, что это «сырая» строка в Python):

result = re.match(r'AV', 'AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result.group(0)

Результат:

AVТеперь попробуем найти «Analytics» в данной строке. Поскольку строка начинается на «AV», метод вернет None:

result = re.match(r'Analytics', 'AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result

Результат:

NoneТакже есть методы start() и end() для того, чтобы узнать начальную и конечную позицию найденной строки.

result = re.match(r'AV', 'AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result.start()

print result.end()

Результат:

0

2Эти методы иногда очень полезны для работы со строками.

re.search(pattern, string)

Метод похож на match(), но ищет не только в начале строки. В отличие от предыдущего, search() вернёт объект, если мы попытаемся найти «Analytics»:

result = re.search(r'Analytics', 'AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result.group(0)

Результат:

AnalyticsМетод search() ищет по всей строке, но возвращает только первое найденное совпадение.

re.findall(pattern, string)

Возвращает список всех найденных совпадений. У метода findall() нет ограничений на поиск в начале или конце строки. Если мы будем искать «AV» в нашей строке, он вернет все вхождения «AV». Для поиска рекомендуется использовать именно findall(), так как он может работать и как re.search(), и как re.match().

result = re.findall(r'AV', 'AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'AV']re.split(pattern, string, [maxsplit=0])

Этот метод разделяет строку по заданному шаблону.

result = re.split(r'y', 'Analytics')

print result

Результат:

['Anal', 'tics']В примере мы разделили слово «Analytics» по букве «y». Метод split() принимает также аргумент maxsplit со значением по умолчанию, равным 0. В данном случае он разделит строку столько раз, сколько возможно, но если указать этот аргумент, то разделение будет произведено не более указанного количества раз. Давайте посмотрим на примеры Python RegEx:

result = re.split(r'i', 'Analytics Vidhya')

print result

Результат:

['Analyt', 'cs V', 'dhya'] # все возможные участки.result = re.split(r'i', 'Analytics Vidhya',maxsplit=1)

print result

Результат:

['Analyt', 'cs Vidhya']Мы установили параметр maxsplit равным 1, и в результате строка была разделена на две части вместо трех.

re.sub(pattern, repl, string)

Ищет шаблон в строке и заменяет его на указанную подстроку. Если шаблон не найден, строка остается неизменной.

result = re.sub(r'India', 'the World', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

'AV is largest Analytics community of the World're.compile(pattern, repl, string)

Мы можем собрать регулярное выражение в отдельный объект, который может быть использован для поиска. Это также избавляет от переписывания одного и того же выражения.

pattern = re.compile('AV')

result = pattern.findall('AV Analytics Vidhya AV')

print result

result2 = pattern.findall('AV is largest analytics community of India')

print result2

Результат:

['AV', 'AV']

['AV']До сих пор мы рассматривали поиск определенной последовательности символов. Но что, если у нас нет определенного шаблона, и нам надо вернуть набор символов из строки, отвечающий определенным правилам? Такая задача часто стоит при извлечении информации из строк. Это можно сделать, написав выражение с использованием специальных символов. Вот наиболее часто используемые из них:

| Оператор | Описание |

|---|---|

| . | Один любой символ, кроме новой строки n. |

| ? | 0 или 1 вхождение шаблона слева |

| + | 1 и более вхождений шаблона слева |

| * | 0 и более вхождений шаблона слева |

| w | Любая цифра или буква (W — все, кроме буквы или цифры) |

| d | Любая цифра [0-9] (D — все, кроме цифры) |

| s | Любой пробельный символ (S — любой непробельный символ) |

| b | Граница слова |

| [..] | Один из символов в скобках ([^..] — любой символ, кроме тех, что в скобках) |

| Экранирование специальных символов (. означает точку или + — знак «плюс») | |

| ^ и $ | Начало и конец строки соответственно |

| {n,m} | От n до m вхождений ({,m} — от 0 до m) |

| a|b | Соответствует a или b |

| () | Группирует выражение и возвращает найденный текст |

| t, n, r | Символ табуляции, новой строки и возврата каретки соответственно |

Больше информации по специальным символам можно найти в документации для регулярных выражений в Python 3.

Перейдём к практическому применению Python регулярных выражений и рассмотрим примеры.

Задачи

Вернуть первое слово из строки

Сначала попробуем вытащить каждый символ (используя .)

result = re.findall(r'.', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['A', 'V', ' ', 'i', 's', ' ', 'l', 'a', 'r', 'g', 'e', 's', 't', ' ', 'A', 'n', 'a', 'l', 'y', 't', 'i', 'c', 's', ' ', 'c', 'o', 'm', 'm', 'u', 'n', 'i', 't', 'y', ' ', 'o', 'f', ' ', 'I', 'n', 'd', 'i', 'a']Для того, чтобы в конечный результат не попал пробел, используем вместо . w.

result = re.findall(r'w', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['A', 'V', 'i', 's', 'l', 'a', 'r', 'g', 'e', 's', 't', 'A', 'n', 'a', 'l', 'y', 't', 'i', 'c', 's', 'c', 'o', 'm', 'm', 'u', 'n', 'i', 't', 'y', 'o', 'f', 'I', 'n', 'd', 'i', 'a']Теперь попробуем достать каждое слово (используя * или +)

result = re.findall(r'w*', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', '', 'is', '', 'largest', '', 'Analytics', '', 'community', '', 'of', '', 'India', '']И снова в результат попали пробелы, так как * означает «ноль или более символов». Для того, чтобы их убрать, используем +:

result = re.findall(r'w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'is', 'largest', 'Analytics', 'community', 'of', 'India']Теперь вытащим первое слово, используя ^:

result = re.findall(r'^w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV']Если мы используем $ вместо ^, то мы получим последнее слово, а не первое:

result = re.findall(r'w+$', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

[‘India’]Вернуть первые два символа каждого слова

Вариант 1: используя w, вытащить два последовательных символа, кроме пробельных, из каждого слова:

result = re.findall(r'ww', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'is', 'la', 'rg', 'es', 'An', 'al', 'yt', 'ic', 'co', 'mm', 'un', 'it', 'of', 'In', 'di']Вариант 2: вытащить два последовательных символа, используя символ границы слова (b):

result = re.findall(r'bw.', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'is', 'la', 'An', 'co', 'of', 'In']Вернуть домены из списка email-адресов

Сначала вернём все символы после «@»:

result = re.findall(r'@w+', 'abc.test@gmail.com, xyz@test.in, test.first@analyticsvidhya.com, first.test@rest.biz')

print result

Результат:

['@gmail', '@test', '@analyticsvidhya', '@rest']Как видим, части «.com», «.in» и т. д. не попали в результат. Изменим наш код:

result = re.findall(r'@w+.w+', 'abc.test@gmail.com, xyz@test.in, test.first@analyticsvidhya.com, first.test@rest.biz')

print result

Результат:

['@gmail.com', '@test.in', '@analyticsvidhya.com', '@rest.biz']Второй вариант — вытащить только домен верхнего уровня, используя группировку — ( ):

result = re.findall(r'@w+.(w+)', 'abc.test@gmail.com, xyz@test.in, test.first@analyticsvidhya.com, first.test@rest.biz')

print result

Результат:

['com', 'in', 'com', 'biz']Извлечь дату из строки

Используем d для извлечения цифр.

result = re.findall(r'd{2}-d{2}-d{4}', 'Amit 34-3456 12-05-2007, XYZ 56-4532 11-11-2011, ABC 67-8945 12-01-2009')

print result

Результат:

['12-05-2007', '11-11-2011', '12-01-2009']Для извлечения только года нам опять помогут скобки:

result = re.findall(r'd{2}-d{2}-(d{4})', 'Amit 34-3456 12-05-2007, XYZ 56-4532 11-11-2011, ABC 67-8945 12-01-2009')

print result

Результат:

['2007', '2011', '2009']Извлечь слова, начинающиеся на гласную

Для начала вернем все слова:

result = re.findall(r'w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'is', 'largest', 'Analytics', 'community', 'of', 'India']А теперь — только те, которые начинаются на определенные буквы (используя []):

result = re.findall(r'[aeiouAEIOU]w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'is', 'argest', 'Analytics', 'ommunity', 'of', 'India']Выше мы видим обрезанные слова «argest» и «ommunity». Для того, чтобы убрать их, используем b для обозначения границы слова:

result = re.findall(r'b[aeiouAEIOU]w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['AV', 'is', 'Analytics', 'of', 'India']Также мы можем использовать ^ внутри квадратных скобок для инвертирования группы:

result = re.findall(r'b[^aeiouAEIOU]w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

[' is', ' largest', ' Analytics', ' community', ' of', ' India']В результат попали слова, «начинающиеся» с пробела. Уберем их, включив пробел в диапазон в квадратных скобках:

result = re.findall(r'b[^aeiouAEIOU ]w+', 'AV is largest Analytics community of India')

print result

Результат:

['largest', 'community']Проверить формат телефонного номера

Номер должен быть длиной 10 знаков и начинаться с 8 или 9. Есть список телефонных номеров, и нужно проверить их, используя регулярки в Python:

li = ['9999999999', '999999-999', '99999x9999']

for val in li:

if re.match(r'[8-9]{1}[0-9]{9}', val) and len(val) == 10:

print 'yes'

else:

print 'no'

Результат:

yes

no

noРазбить строку по нескольким разделителям

Возможное решение:

line = 'asdf fjdk;afed,fjek,asdf,foo' # String has multiple delimiters (";",","," ").

result = re.split(r'[;,s]', line)

print result

Результат:

['asdf', 'fjdk', 'afed', 'fjek', 'asdf', 'foo']Также мы можем использовать метод re.sub() для замены всех разделителей пробелами:

line = 'asdf fjdk;afed,fjek,asdf,foo'

result = re.sub(r'[;,s]',' ', line)

print result

Результат:

asdf fjdk afed fjek asdf fooИзвлечь информацию из html-файла

Допустим, нужно извлечь информацию из html-файла, заключенную между <td> и </td>, кроме первого столбца с номером. Также будем считать, что html-код содержится в строке.

Пример содержимого html-файла:

1NoahEmma2LiamOlivia3MasonSophia4JacobIsabella5WilliamAva6EthanMia7MichaelEmilyС помощью регулярных выражений в Python это можно решить так (если поместить содержимое файла в переменную test_str):

result = re.findall(r'd([A-Z][A-Za-z]+)([A-Z][A-Za-z]+)', test_str)

print result

Результат:

[('Noah', 'Emma'), ('Liam', 'Olivia'), ('Mason', 'Sophia'), ('Jacob', 'Isabella'), ('William', 'Ava'), ('Ethan', 'Mia'), ('Michael', 'Emily')]Адаптированный перевод «Beginners Tutorial for Regular Expressions in Python»

Что такое Regex

Регулярные выражения (Regex) – это строки, задающие шаблон для поиска определенных фрагментов в тексте. Помимо поиска, с помощью специальных Regex-шаблонов можно манипулировать текстовыми фрагментами – удалять и изменять подстроки частично или полностью.

Регулярные выражения состоят из набора литералов (букв и цифр) и метасимволов и выглядят примерно так: r'(https?://)?(www.)?youtube.(com|nl)/watch?v=([w-]+)(&.*?)?(?=[^-w&=%])'Используя метасимволы, можно создавать сложные шаблоны, содержащие специальные конструкции для работы с определенными последовательностями и группами символов.

Regex-выражения применяют для обработки текстовых данных, в том числе в скриптах для веб-скрапинга. Кроме того, Regex используют в составе OCR-приложений для очистки отсканированного текста.

Regex в Python

Большинство современных языков программирования поддерживают регулярные выражения, однако степень удобства использования Regex в разных языках варьируется. Python предоставляет простые и понятные методы для работы с регулярными выражениями. Все Regex инструменты находятся в модуле re, который входит в стандартный дистрибутив Python – достаточно импортировать его в свой проект:

import re

Для экранирования служебных символов в шаблонах поиска и замены используют два способа – обратный слэш и «сырые» строки r''. Второй метод предпочтительнее – он позволяет избежать нагромождения слэшей в шаблонах.

Основные функции Regex

re.match() – находит вхождение фрагмента в начале строки. Обычный формат использования – re.match(r'шаблон', строка):

import re

s = "утка крякает, кукушка кукует, петух кукарекает"

match = re.match(r'ку', s)

print(match)

Этот код вернет None, несмотря на то, что в строке есть 5 фрагментов «ку». Это происходит потому, что оба фрагмента расположены не в начале строки.

re.search() – находит первое вхождение фрагмента в любом месте и возвращает объект match. Если в строке есть другие фрагменты, соответствующие запросу, re.search их проигнорирует. У re.search есть дополнительные методы:

.span() – возвращает кортеж, содержащий начальную и конечную позиции искомого фрагмента.

.string – вернет строку, переданную в функцию re.search.

.group() – возвращает фрагмент строки, в котором было обнаружено совпадение.

#Пример использования re.search с дополнительными методами

import re

s = "oт топота копыт пыль по полю летит"

match = re.search(r'по', s)

print(match, match.span(), match.string, match.group(), sep='n')

#Вывод:

<re.Match object; span=(5, 7), match='по'>

(5, 7)

oт топота копыт пыль по полю летит

по

re.findall() – находит все вхождения фрагмента, в любом месте. Функция re.findall() учитывает регистр символов. Чтобы в результат вошли фрагменты с символами в другом регистре, применяют флаг re.IGNORECASE:

import re

s = "Не видно, ликвидны акции или неликвидны."

match = re.findall(r'не', s, re.I)

print(match)

re.split() – расщепляет строку по заданному шаблону. Количество расщеплений задается флагом – в этом примере от строки отделяется только первое слово:

import re

s = "Обладаешь ли ты налогооблагаемой благодатью?"

res = re.split(r' ', s, 1)

print(res)

re.sub() – заменяет фрагмент в соответствии с шаблоном:

import re

s = "Коала какао лениво лакала"

res = re.sub(r'коала', 'макака', s, flags=re.I)

print(res)

re.compile() – создает объект из регулярного выражения. Применяется, если один и тот же поисковый шаблон используется в коде несколько раз:

import re

st = re.compile('угнал')

res1 = st.findall("Карл у Клары угнал Maclaren, а Клара у Карла угнала Corvette.")

res2 = st.findall("Карл у Клары угнал кораллы, а Клара у Карла угнала кларнет.")

print(res1, res2, sep='n')

Все перечисленные выше примеры предназначены для выполнения самых простых задач по поиску и замене фрагментов текста. Возможности Regex в Python намного шире: шаблоны могут включать условия, учитывать (или игнорировать) группы символов и диапазоны значений. Для создания таких регулярных выражений используют специальные конструкции, состоящие из метасимволов.

Основные метасимволы в Regex

[] – используется для указания набора или диапазона символов – re.findall(r'[с-я]', "Камер-юнкер юркнул в бункер", re.I), re.findall(r'[аж]', "ажиотаж, мандраж, багаж").

– указывает на начало последовательности (мы рассмотрим их ниже) или экранирует служебные символы.

. – выбирает любой символ, кроме новой строки n.

^ – проверяет, начинается ли строка с определенного символа / слова / набора символов. Например, r'^Привет‘ проверит, начинается ли строка с «Привет». Метасимвол ^ в наборе [] имеет другое значение – проверяет, отсутствуют ли в строке определенные символы (подробнее об этом ниже).

$ – проверяет, заканчивается ли строка в соответствии с шаблоном r'До свиданья.$'.

* – ноль или больше совпадений с шаблоном r'ко.*аборация'.

+ – одно и более совпадений r'к.+ператив'.

? – ноль или одно совпадение r'ф.?нтастика'. Кроме того, нейтрализует «жадность» выражений, которые используют ., *, + для выбора любых символов.

{} – точное число совпадений r'Интерсте.{2}ар'.

| – любой из двух вариантов r'уйду|останусь'.

() – захватывает группу для дальнейших манипуляций – re.sub(r'(www)', r'1.', "wwwwear-gear.com").

<> – создает именованную группу – re.search('(?P<группа1>w+),(?P<группа2>w+),(?P<группа3>w+)', 'дом,улица,фонарь')

Последовательности

Знаком слэша обозначается специфическая последовательность символов.

A – проверяет, начинается ли строка с определенной последовательности символов. Например, re.findall(r"AДом", txt), проверит, начинается ли предложение со слова «Дом».

b – возвращает совпадение, если слово начинается или заканчивается нужной последовательностью символов. Выражение re.findall(r".comb", s) проверит, есть ли в строке хотя бы одно доменное имя зоны .com.

B – возвращает совпадение, если определенные символы есть в строке, но не в начале или не в конце слова – re.findall(r"Bро", 'розовая от мороза'), re.findall(r'инB', 'синий апельсин').

d – проверяет, что в строке есть цифры от 0 до 9 – re.findall("d", 'при пожаре звоните 112').

D – удостоверяет, что цифр в строке нет – re.findall("D", 'цифр нет').

s – проверяет наличие пробелов в строке – re.findall("s", "один пробел").

S – возвращает совпадение, если в строке есть любые символы, кроме пробелов – re.findall("S", "непустая строка").

w – проверяет, есть ли в строке «словесные» символы – знак нижнего подчеркивания, цифры и буквы – re.findall(r"w", "_\\").

W – возвращает совпадение по каждому «несловесному» символу – re.findall("W", "здесь есть такие символы!").

Z – проверит, заканчивается ли строка нужной последовательностью символов – re.findall("конецZ", "это конец").

Наборы и диапазоны символов

Наборы и диапазоны в регулярных выражениях заключены в квадратные скобки:

[есн] – проверит, есть ли в строке любой из указанных символов е, с или н – re.findall("[есн]", "здесь есть несколько символов из набора"). Наличие любой цифры из набора проверяется так же – [0169].

[а-е] – вернет совпадения по каждому символу из алфавитного диапазона – re.findall("[а-е]", "здесь есть символы из диапазона"). Таким же образом возвращает совпадения по диапазону цифр – [5-9]. Чтобы не использовать флаг re.IGNORECASE, диапазон можно указывать так – [а-еА-Е].

[^абвгд] – проверит наличие в строке символов, кроме указанных в наборе – re.findall("[^абвгд]", "АБВГДейка – детская передача", re.I).

[0-5][0-9] – возвращает совпадения по двузначным цифрам от 00 до 59 – re.findall("[0-5][0-9]", "будильник сработает в 07:45").

Флаги в Regex

Функциональность регулярных выражений расширяется за счет флагов:

| Краткий синтаксис | Полный синтаксис | Назначение |

| re.A | re.ASCII | Возвращает совпадения только по ASCII-символам вместо всей таблицы Unicode. |

| re.I | re.IGNORECASE | Игнорирует регистр символов. |

| re.M | re.MULTILINE | Используется совместно с метасимволами ^ и $. В первом случае возвращает совпадения в начале каждой новой строки n, во втором – в конце n. |

| re.S | re.DOTALL | Заставляет метасимвол . возвращать совпадения по абсолютно всем символам, включая n. Без этого флага точка . соответствует любому символу, кроме n. |

| re.X | re.VERBOSE | Разрешает комментарии в Regex-выражениях. |

| re.L | re.LOCALE | Учитывает региональные настройки при использовании w, W, b, B, s и S. Используется только при работе с байтовыми строками, не совместим с re.ASCII. |

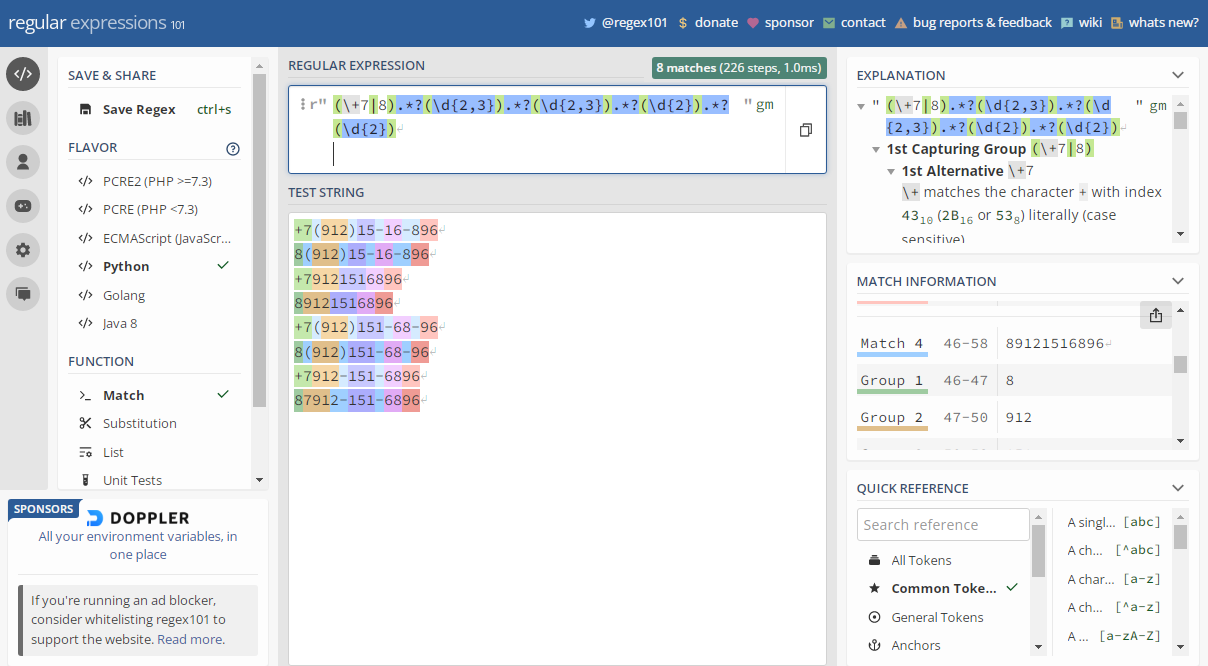

Онлайн-конструкторы регулярных выражений

Чем сложнее регулярное выражение, тем труднее его правильно составить и протестировать. В интернете есть немало визуализаторов Regex, которые значительно упрощают эту задачу. Самый удобный ресурс – regex101. Сайт предоставляет справочную и отладочную информацию, позволяет визуально тестировать шаблоны для поиска и замены. Помимо Python, поддерживает PHP, Java, Golang и JavaScript.

Задача 1:

Написать регулярное выражение для извлечения из текста всех email-адресов.

Решение:

import re

s = 'По всем вопросам пишите на vasiliy-pupkin@gmail.com, или на secondemail@yandex.ru, отвечу сразу. Или пишите моему ассистенту secretary@gmail.com!'

emails = re.findall(r'[w.-]+@[w.-]+', s)

for email in emails:

print(email)

Задача 2:

Имеется файл transactions.txt, в котором даты указаны в формате MM/DD/YYYY, при этом в некоторых случаях месяц обозначен первыми тремя буквами: NOV, dec, JAN. Нужно привести даты к формату MM-DD-YYYY.

#формат дат в файле transactions.txt

nov/14/2021

dec/15/2021

12/16/2021

dec/17/2021

jan/03/2022

JAN/10/22

Решение:

import fileinput

import re

fn = "transactions.txt"

for line in fileinput.input(fn, inplace=True):

new_line = re.sub('(d{2}|[a-yA-Y]{3})/(d{2})/(d{2, 4})', r'1-2-3', line)

print(new_line)

#Содержимое файла после выполнения кода:

nov-14-2021

dec-15-2021

12-16-2021

dec-17-2021

jan-03-2022

JAN-10-2022

Задача 3:

Вводится последовательность строк. Нужно вывести строки, в которых фрагмент «кот» присутствует в качестве подстроки не менее 2 раз.

#Пример ввода

кот-кот

кот и кот

котофей

котейка кот

кот и котенок

Решение:

import re

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

if re.search(r"кот.*?кот", line):

print(line)

Задача 4:

Дана последовательность строк. Нужно вывести те, в которых «кот» встречается в качестве отдельного слова.

#Пример ввода:

кот в сапогах

кошка и кот

котофей

котяра

Решение:

import re

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.rstrip()

if re.search(r"bкотb", line):

print(line)

#Вывод

кот в сапогах

кошка и кот

Задача 5:

Вывести слова, состоящие из двух одинаковых слогов.

#Пример ввода

тартар

тик-так

сносно

варвар

барабан

Решение:

import re

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

if re.search(r"b(w+)1b", line):

print(line)

#Вывод

тартар

сносно

варвар

Задача 6:

Вводится последовательность строк. В каждой строке нужно поменять местами две первые буквы в каждом слове, состоящем из двух и более букв.

#Пример ввода

это пример текста

в котором нужно поменять буквы

Решение:

import sys

import re

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.rstrip()

print(re.sub(r'b(w)(w)', r"21", line))

#Вывод

тэо рпимер еткста

в октором унжно опменять убквы

Задача 7:

Напишите функцию для валидации мобильного номера в международном формате. Корректным считается представление номера в таком виде:

+7(912)15-16-896, 8(912)15-16-896

+79121516896, 89121516896

+7(912)151-68-96, 8(912)151-68-96

+7912-151-6896, 87912-151-6896

Решение:

import re

pattern = re.compile(r'(+7|8).*?(d{2,3}).*?(d{2,3}).*?(d{2}).*?(d{2})')

def isValid(number):

if re.match(pattern, number):

print("ДА")

else:

print("НЕТ")

isValid(input())

Задача 8:

Напишите программу для парсинга номеров телефонов с тестовой страницы.

Решение:

import urllib.request

from re import findall

url = "http://www.summet.com/dmsi/html/codesamples/addresses.html"

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

data = response.read()

s = data.decode()

phones = findall("(d{3}) d{3}-d{4}", s)

for number in phones:

print(number)

Задача 9:

Нужно извлечь все имена и фамилии из текста.

Решение:

import re

s = 'На встрече присутствовали: профессор Владимир Успенский, физик-ядерщик Сергей Ковалев, президент клуба Владимир Медведев и космонавт Юрий Титов.'

name = r"[А-Я][а-я]+,?s+"

last_name = r"[А-Я][а-я]+"

persons = re.findall(name + last_name, s)

for item in persons:

print(item)

Задача 10:

Нужно получить URL всех png и jpg изображений, использованных на главной странице proglib.io:

import re

import requests

def getURL(text):

urls = []

results = re.findall(r'(?:http:|https:)?//.*.(?:png|jpg)', text)

for x in results:

if not x.startswith('http:'):

x = 'http:' + x

urls.append(x)

return urls

def getImages(url):

resp = requests.get(url)

urls = getURL(resp.text)

print('urls', urls)

getImages('https://proglib.io')

Заключение

Regex в Python – мощный, гибкий, но достаточно сложный инструмент. Регулярные выражения сложно составлять, поддерживать и редактировать. При работе с текстовыми файлами Regex чаще всего можно заменить методами строк, а при парсинге, в большинстве случаев, использование XPath и CSS-селекторов окажется более эффективным.

***

Материалы по теме

- Регулярные выражения: 5 сервисов для тестирования и отладки

- Практическое введение в регулярные выражения для новичков

- Регулярные выражения: базовое знакомство для новичков

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Regular Expressions and Building Regexes in Python

In this tutorial, you’ll explore regular expressions, also known as regexes, in Python. A regex is a special sequence of characters that defines a pattern for complex string-matching functionality.

Earlier in this series, in the tutorial Strings and Character Data in Python, you learned how to define and manipulate string objects. Since then, you’ve seen some ways to determine whether two strings match each other:

-

You can test whether two strings are equal using the equality (

==) operator. -

You can test whether one string is a substring of another with the

inoperator or the built-in string methods.find()and.index().

String matching like this is a common task in programming, and you can get a lot done with string operators and built-in methods. At times, though, you may need more sophisticated pattern-matching capabilities.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn:

- How to access the

remodule, which implements regex matching in Python - How to use

re.search()to match a pattern against a string - How to create complex matching pattern with regex metacharacters

Fasten your seat belt! Regex syntax takes a little getting used to. But once you get comfortable with it, you’ll find regexes almost indispensable in your Python programming.

Regexes in Python and Their Uses

Imagine you have a string object s. Now suppose you need to write Python code to find out whether s contains the substring '123'. There are at least a couple ways to do this. You could use the in operator:

>>>

>>> s = 'foo123bar'

>>> '123' in s

True

If you want to know not only whether '123' exists in s but also where it exists, then you can use .find() or .index(). Each of these returns the character position within s where the substring resides:

>>>

>>> s = 'foo123bar'

>>> s.find('123')

3

>>> s.index('123')

3

In these examples, the matching is done by a straightforward character-by-character comparison. That will get the job done in many cases. But sometimes, the problem is more complicated than that.

For example, rather than searching for a fixed substring like '123', suppose you wanted to determine whether a string contains any three consecutive decimal digit characters, as in the strings 'foo123bar', 'foo456bar', '234baz', and 'qux678'.

Strict character comparisons won’t cut it here. This is where regexes in Python come to the rescue.

A (Very Brief) History of Regular Expressions

In 1951, mathematician Stephen Cole Kleene described the concept of a regular language, a language that is recognizable by a finite automaton and formally expressible using regular expressions. In the mid-1960s, computer science pioneer Ken Thompson, one of the original designers of Unix, implemented pattern matching in the QED text editor using Kleene’s notation.

Since then, regexes have appeared in many programming languages, editors, and other tools as a means of determining whether a string matches a specified pattern. Python, Java, and Perl all support regex functionality, as do most Unix tools and many text editors.

The re Module

Regex functionality in Python resides in a module named re. The re module contains many useful functions and methods, most of which you’ll learn about in the next tutorial in this series.

For now, you’ll focus predominantly on one function, re.search().

re.search(<regex>, <string>)

Scans a string for a regex match.

re.search(<regex>, <string>) scans <string> looking for the first location where the pattern <regex> matches. If a match is found, then re.search() returns a match object. Otherwise, it returns None.

re.search() takes an optional third <flags> argument that you’ll learn about at the end of this tutorial.

How to Import re.search()

Because search() resides in the re module, you need to import it before you can use it. One way to do this is to import the entire module and then use the module name as a prefix when calling the function:

Alternatively, you can import the function from the module by name and then refer to it without the module name prefix:

from re import search

search(...)

You’ll always need to import re.search() by one means or another before you’ll be able to use it.

The examples in the remainder of this tutorial will assume the first approach shown—importing the re module and then referring to the function with the module name prefix: re.search(). For the sake of brevity, the import re statement will usually be omitted, but remember that it’s always necessary.

For more information on importing from modules and packages, check out Python Modules and Packages—An Introduction.

First Pattern-Matching Example

Now that you know how to gain access to re.search(), you can give it a try:

>>>

1>>> s = 'foo123bar'

2

3>>> # One last reminder to import!

4>>> import re

5

6>>> re.search('123', s)

7<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='123'>

Here, the search pattern <regex> is 123 and <string> is s. The returned match object appears on line 7. Match objects contain a wealth of useful information that you’ll explore soon.

For the moment, the important point is that re.search() did in fact return a match object rather than None. That tells you that it found a match. In other words, the specified <regex> pattern 123 is present in s.

A match object is truthy, so you can use it in a Boolean context like a conditional statement:

>>>

>>> if re.search('123', s):

... print('Found a match.')

... else:

... print('No match.')

...

Found a match.

The interpreter displays the match object as <_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='123'>. This contains some useful information.

span=(3, 6) indicates the portion of <string> in which the match was found. This means the same thing as it would in slice notation:

In this example, the match starts at character position 3 and extends up to but not including position 6.

match='123' indicates which characters from <string> matched.

This is a good start. But in this case, the <regex> pattern is just the plain string '123'. The pattern matching here is still just character-by-character comparison, pretty much the same as the in operator and .find() examples shown earlier. The match object helpfully tells you that the matching characters were '123', but that’s not much of a revelation since those were exactly the characters you searched for.

You’re just getting warmed up.

Python Regex Metacharacters

The real power of regex matching in Python emerges when <regex> contains special characters called metacharacters. These have a unique meaning to the regex matching engine and vastly enhance the capability of the search.

Consider again the problem of how to determine whether a string contains any three consecutive decimal digit characters.

In a regex, a set of characters specified in square brackets ([]) makes up a character class. This metacharacter sequence matches any single character that is in the class, as demonstrated in the following example:

>>>

>>> s = 'foo123bar'

>>> re.search('[0-9][0-9][0-9]', s)

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='123'>

[0-9] matches any single decimal digit character—any character between '0' and '9', inclusive. The full expression [0-9][0-9][0-9] matches any sequence of three decimal digit characters. In this case, s matches because it contains three consecutive decimal digit characters, '123'.

These strings also match:

>>>

>>> re.search('[0-9][0-9][0-9]', 'foo456bar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='456'>

>>> re.search('[0-9][0-9][0-9]', '234baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 3), match='234'>

>>> re.search('[0-9][0-9][0-9]', 'qux678')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='678'>

On the other hand, a string that doesn’t contain three consecutive digits won’t match:

>>>

>>> print(re.search('[0-9][0-9][0-9]', '12foo34'))

None

With regexes in Python, you can identify patterns in a string that you wouldn’t be able to find with the in operator or with string methods.

Take a look at another regex metacharacter. The dot (.) metacharacter matches any character except a newline, so it functions like a wildcard:

>>>

>>> s = 'foo123bar'

>>> re.search('1.3', s)

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='123'>

>>> s = 'foo13bar'

>>> print(re.search('1.3', s))

None

In the first example, the regex 1.3 matches '123' because the '1' and '3' match literally, and the . matches the '2'. Here, you’re essentially asking, “Does s contain a '1', then any character (except a newline), then a '3'?” The answer is yes for 'foo123bar' but no for 'foo13bar'.

These examples provide a quick illustration of the power of regex metacharacters. Character class and dot are but two of the metacharacters supported by the re module. There are many more. Next, you’ll explore them fully.

The following table briefly summarizes all the metacharacters supported by the re module. Some characters serve more than one purpose:

| Character(s) | Meaning |

|---|---|

. |

Matches any single character except newline |

^ |

∙ Anchors a match at the start of a string ∙ Complements a character class |

$ |

Anchors a match at the end of a string |

* |

Matches zero or more repetitions |

+ |

Matches one or more repetitions |

? |

∙ Matches zero or one repetition ∙ Specifies the non-greedy versions of *, +, and ?∙ Introduces a lookahead or lookbehind assertion ∙ Creates a named group |

{} |

Matches an explicitly specified number of repetitions |

|

∙ Escapes a metacharacter of its special meaning ∙ Introduces a special character class ∙ Introduces a grouping backreference |

[] |

Specifies a character class |

| |

Designates alternation |

() |

Creates a group |

:#=! |

Designate a specialized group |

<> |

Creates a named group |

This may seem like an overwhelming amount of information, but don’t panic! The following sections go over each one of these in detail.

The regex parser regards any character not listed above as an ordinary character that matches only itself. For example, in the first pattern-matching example shown above, you saw this:

>>>

>>> s = 'foo123bar'

>>> re.search('123', s)

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='123'>

In this case, 123 is technically a regex, but it’s not a very interesting one because it doesn’t contain any metacharacters. It just matches the string '123'.

Things get much more exciting when you throw metacharacters into the mix. The following sections explain in detail how you can use each metacharacter or metacharacter sequence to enhance pattern-matching functionality.

Metacharacters That Match a Single Character

The metacharacter sequences in this section try to match a single character from the search string. When the regex parser encounters one of these metacharacter sequences, a match happens if the character at the current parsing position fits the description that the sequence describes.

[]

Specifies a specific set of characters to match.

Characters contained in square brackets ([]) represent a character class—an enumerated set of characters to match from. A character class metacharacter sequence will match any single character contained in the class.

You can enumerate the characters individually like this:

>>>

>>> re.search('ba[artz]', 'foobarqux')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='bar'>

>>> re.search('ba[artz]', 'foobazqux')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='baz'>

The metacharacter sequence [artz] matches any single 'a', 'r', 't', or 'z' character. In the example, the regex ba[artz] matches both 'bar' and 'baz' (and would also match 'baa' and 'bat').

A character class can also contain a range of characters separated by a hyphen (-), in which case it matches any single character within the range. For example, [a-z] matches any lowercase alphabetic character between 'a' and 'z', inclusive:

>>>

>>> re.search('[a-z]', 'FOObar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='b'>

[0-9] matches any digit character:

>>>

>>> re.search('[0-9][0-9]', 'foo123bar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 5), match='12'>

In this case, [0-9][0-9] matches a sequence of two digits. The first portion of the string 'foo123bar' that matches is '12'.

[0-9a-fA-F] matches any hexadecimal digit character:

>>>

>>> re.search('[0-9a-fA-f]', '--- a0 ---')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 5), match='a'>

Here, [0-9a-fA-F] matches the first hexadecimal digit character in the search string, 'a'.

You can complement a character class by specifying ^ as the first character, in which case it matches any character that isn’t in the set. In the following example, [^0-9] matches any character that isn’t a digit:

>>>

>>> re.search('[^0-9]', '12345foo')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(5, 6), match='f'>

Here, the match object indicates that the first character in the string that isn’t a digit is 'f'.

If a ^ character appears in a character class but isn’t the first character, then it has no special meaning and matches a literal '^' character:

>>>

>>> re.search('[#:^]', 'foo^bar:baz#qux')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='^'>

As you’ve seen, you can specify a range of characters in a character class by separating characters with a hyphen. What if you want the character class to include a literal hyphen character? You can place it as the first or last character or escape it with a backslash ():

>>>

>>> re.search('[-abc]', '123-456')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='-'>

>>> re.search('[abc-]', '123-456')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='-'>

>>> re.search('[ab-c]', '123-456')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='-'>

If you want to include a literal ']' in a character class, then you can place it as the first character or escape it with backslash:

>>>

>>> re.search('[]]', 'foo[1]')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(5, 6), match=']'>

>>> re.search('[ab]cd]', 'foo[1]')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(5, 6), match=']'>

Other regex metacharacters lose their special meaning inside a character class:

>>>

>>> re.search('[)*+|]', '123*456')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='*'>

>>> re.search('[)*+|]', '123+456')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='+'>

As you saw in the table above, * and + have special meanings in a regex in Python. They designate repetition, which you’ll learn more about shortly. But in this example, they’re inside a character class, so they match themselves literally.

dot (.)

Specifies a wildcard.

The . metacharacter matches any single character except a newline:

>>>

>>> re.search('foo.bar', 'fooxbar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='fooxbar'>

>>> print(re.search('foo.bar', 'foobar'))

None

>>> print(re.search('foo.bar', 'foonbar'))

None

As a regex, foo.bar essentially means the characters 'foo', then any character except newline, then the characters 'bar'. The first string shown above, 'fooxbar', fits the bill because the . metacharacter matches the 'x'.

The second and third strings fail to match. In the last case, although there’s a character between 'foo' and 'bar', it’s a newline, and by default, the . metacharacter doesn’t match a newline. There is, however, a way to force . to match a newline, which you’ll learn about at the end of this tutorial.

wW

Match based on whether a character is a word character.

w matches any alphanumeric word character. Word characters are uppercase and lowercase letters, digits, and the underscore (_) character, so w is essentially shorthand for [a-zA-Z0-9_]:

>>>

>>> re.search('w', '#(.a$@&')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='a'>

>>> re.search('[a-zA-Z0-9_]', '#(.a$@&')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='a'>

In this case, the first word character in the string '#(.a$@&' is 'a'.

W is the opposite. It matches any non-word character and is equivalent to [^a-zA-Z0-9_]:

>>>

>>> re.search('W', 'a_1*3Qb')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='*'>

>>> re.search('[^a-zA-Z0-9_]', 'a_1*3Qb')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='*'>

Here, the first non-word character in 'a_1*3!b' is '*'.

dD

Match based on whether a character is a decimal digit.

d matches any decimal digit character. D is the opposite. It matches any character that isn’t a decimal digit:

>>>

>>> re.search('d', 'abc4def')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='4'>

>>> re.search('D', '234Q678')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='Q'>

d is essentially equivalent to [0-9], and D is equivalent to [^0-9].

sS

Match based on whether a character represents whitespace.

s matches any whitespace character:

>>>

>>> re.search('s', 'foonbar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='n'>

Note that, unlike the dot wildcard metacharacter, s does match a newline character.

S is the opposite of s. It matches any character that isn’t whitespace:

>>>

>>> re.search('S', ' n foo n ')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 5), match='f'>

Again, s and S consider a newline to be whitespace. In the example above, the first non-whitespace character is 'f'.

The character class sequences w, W, d, D, s, and S can appear inside a square bracket character class as well:

>>>

>>> re.search('[dws]', '---3---')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='3'>

>>> re.search('[dws]', '---a---')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='a'>

>>> re.search('[dws]', '--- ---')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match=' '>

In this case, [dws] matches any digit, word, or whitespace character. And since w includes d, the same character class could also be expressed slightly shorter as [ws].

Escaping Metacharacters

Occasionally, you’ll want to include a metacharacter in your regex, except you won’t want it to carry its special meaning. Instead, you’ll want it to represent itself as a literal character.

backslash ()

Removes the special meaning of a metacharacter.

As you’ve just seen, the backslash character can introduce special character classes like word, digit, and whitespace. There are also special metacharacter sequences called anchors that begin with a backslash, which you’ll learn about below.

When it’s not serving either of these purposes, the backslash escapes metacharacters. A metacharacter preceded by a backslash loses its special meaning and matches the literal character instead. Consider the following examples:

>>>

1>>> re.search('.', 'foo.bar')

2<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 1), match='f'>

3

4>>> re.search('.', 'foo.bar')

5<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='.'>

In the <regex> on line 1, the dot (.) functions as a wildcard metacharacter, which matches the first character in the string ('f'). The . character in the <regex> on line 4 is escaped by a backslash, so it isn’t a wildcard. It’s interpreted literally and matches the '.' at index 3 of the search string.

Using backslashes for escaping can get messy. Suppose you have a string that contains a single backslash:

>>>

>>> s = r'foobar'

>>> print(s)

foobar

Now suppose you want to create a <regex> that will match the backslash between 'foo' and 'bar'. The backslash is itself a special character in a regex, so to specify a literal backslash, you need to escape it with another backslash. If that’s that case, then the following should work:

>>>

>>> re.search('\', s)

Not quite. This is what you get if you try it:

>>>

>>> re.search('\', s)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#3>", line 1, in <module>

re.search('\', s)

File "C:Python36libre.py", line 182, in search

return _compile(pattern, flags).search(string)

File "C:Python36libre.py", line 301, in _compile

p = sre_compile.compile(pattern, flags)

File "C:Python36libsre_compile.py", line 562, in compile

p = sre_parse.parse(p, flags)

File "C:Python36libsre_parse.py", line 848, in parse

source = Tokenizer(str)

File "C:Python36libsre_parse.py", line 231, in __init__

self.__next()

File "C:Python36libsre_parse.py", line 245, in __next

self.string, len(self.string) - 1) from None

sre_constants.error: bad escape (end of pattern) at position 0

Oops. What happened?

The problem here is that the backslash escaping happens twice, first by the Python interpreter on the string literal and then again by the regex parser on the regex it receives.

Here’s the sequence of events:

- The Python interpreter is the first to process the string literal

'\'. It interprets that as an escaped backslash and passes only a single backslash tore.search(). - The regex parser receives just a single backslash, which isn’t a meaningful regex, so the messy error ensues.

There are two ways around this. First, you can escape both backslashes in the original string literal:

>>>

>>> re.search('\\', s)

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='\'>

Doing so causes the following to happen:

- The interpreter sees

'\\'as a pair of escaped backslashes. It reduces each pair to a single backslash and passes'\'to the regex parser. - The regex parser then sees

\as one escaped backslash. As a<regex>, that matches a single backslash character. You can see from the match object that it matched the backslash at index3insas intended. It’s cumbersome, but it works.

The second, and probably cleaner, way to handle this is to specify the <regex> using a raw string:

>>>

>>> re.search(r'\', s)

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 4), match='\'>

This suppresses the escaping at the interpreter level. The string '\' gets passed unchanged to the regex parser, which again sees one escaped backslash as desired.

It’s good practice to use a raw string to specify a regex in Python whenever it contains backslashes.

Anchors

Anchors are zero-width matches. They don’t match any actual characters in the search string, and they don’t consume any of the search string during parsing. Instead, an anchor dictates a particular location in the search string where a match must occur.

^A

Anchor a match to the start of

<string>.

When the regex parser encounters ^ or A, the parser’s current position must be at the beginning of the search string for it to find a match.

In other words, regex ^foo stipulates that 'foo' must be present not just any old place in the search string, but at the beginning:

>>>

>>> re.search('^foo', 'foobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 3), match='foo'>

>>> print(re.search('^foo', 'barfoo'))

None

A functions similarly:

>>>

>>> re.search('Afoo', 'foobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 3), match='foo'>

>>> print(re.search('Afoo', 'barfoo'))

None

^ and A behave slightly differently from each other in MULTILINE mode. You’ll learn more about MULTILINE mode below in the section on flags.

$Z

Anchor a match to the end of

<string>.

When the regex parser encounters $ or Z, the parser’s current position must be at the end of the search string for it to find a match. Whatever precedes $ or Z must constitute the end of the search string:

>>>

>>> re.search('bar$', 'foobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='bar'>

>>> print(re.search('bar$', 'barfoo'))

None

>>> re.search('barZ', 'foobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='bar'>

>>> print(re.search('barZ', 'barfoo'))

None

As a special case, $ (but not Z) also matches just before a single newline at the end of the search string:

>>>

>>> re.search('bar$', 'foobarn')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='bar'>

In this example, 'bar' isn’t technically at the end of the search string because it’s followed by one additional newline character. But the regex parser lets it slide and calls it a match anyway. This exception doesn’t apply to Z.

$ and Z behave slightly differently from each other in MULTILINE mode. See the section below on flags for more information on MULTILINE mode.

b

Anchors a match to a word boundary.

b asserts that the regex parser’s current position must be at the beginning or end of a word. A word consists of a sequence of alphanumeric characters or underscores ([a-zA-Z0-9_]), the same as for the w character class:

>>>

1>>> re.search(r'bbar', 'foo bar')

2<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

3>>> re.search(r'bbar', 'foo.bar')

4<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

5

6>>> print(re.search(r'bbar', 'foobar'))

7None

8

9>>> re.search(r'foob', 'foo bar')

10<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 3), match='foo'>

11>>> re.search(r'foob', 'foo.bar')

12<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 3), match='foo'>

13

14>>> print(re.search(r'foob', 'foobar'))

15None

In the above examples, a match happens on lines 1 and 3 because there’s a word boundary at the start of 'bar'. This isn’t the case on line 6, so the match fails there.

Similarly, there are matches on lines 9 and 11 because a word boundary exists at the end of 'foo', but not on line 14.

Using the b anchor on both ends of the <regex> will cause it to match when it’s present in the search string as a whole word:

>>>

>>> re.search(r'bbarb', 'foo bar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

>>> re.search(r'bbarb', 'foo(bar)baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

>>> print(re.search(r'bbarb', 'foobarbaz'))

None

This is another instance in which it pays to specify the <regex> as a raw string, as the above examples have done.

Because 'b' is an escape sequence for both string literals and regexes in Python, each use above would need to be double escaped as '\b' if you didn’t use raw strings. That wouldn’t be the end of the world, but raw strings are tidier.

B

Anchors a match to a location that isn’t a word boundary.

B does the opposite of b. It asserts that the regex parser’s current position must not be at the start or end of a word:

>>>

1>>> print(re.search(r'BfooB', 'foo'))

2None

3>>> print(re.search(r'BfooB', '.foo.'))

4None

5

6>>> re.search(r'BfooB', 'barfoobaz')

7<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(3, 6), match='foo'>

In this case, a match happens on line 7 because no word boundary exists at the start or end of 'foo' in the search string 'barfoobaz'.

Quantifiers

A quantifier metacharacter immediately follows a portion of a <regex> and indicates how many times that portion must occur for the match to succeed.

*

Matches zero or more repetitions of the preceding regex.

For example, a* matches zero or more 'a' characters. That means it would match an empty string, 'a', 'aa', 'aaa', and so on.

Consider these examples:

>>>

1>>> re.search('foo-*bar', 'foobar') # Zero dashes

2<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 6), match='foobar'>

3>>> re.search('foo-*bar', 'foo-bar') # One dash

4<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='foo-bar'>

5>>> re.search('foo-*bar', 'foo--bar') # Two dashes

6<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 8), match='foo--bar'>

On line 1, there are zero '-' characters between 'foo' and 'bar'. On line 3 there’s one, and on line 5 there are two. The metacharacter sequence -* matches in all three cases.

You’ll probably encounter the regex .* in a Python program at some point. This matches zero or more occurrences of any character. In other words, it essentially matches any character sequence up to a line break. (Remember that the . wildcard metacharacter doesn’t match a newline.)

In this example, .* matches everything between 'foo' and 'bar':

>>>

>>> re.search('foo.*bar', '# foo $qux@grault % bar #')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(2, 23), match='foo $qux@grault % bar'>

Did you notice the span= and match= information contained in the match object?

Until now, the regexes in the examples you’ve seen have specified matches of predictable length. Once you start using quantifiers like *, the number of characters matched can be quite variable, and the information in the match object becomes more useful.

You’ll learn more about how to access the information stored in a match object in the next tutorial in the series.

+

Matches one or more repetitions of the preceding regex.

This is similar to *, but the quantified regex must occur at least once:

>>>

1>>> print(re.search('foo-+bar', 'foobar')) # Zero dashes

2None

3>>> re.search('foo-+bar', 'foo-bar') # One dash

4<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='foo-bar'>

5>>> re.search('foo-+bar', 'foo--bar') # Two dashes

6<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 8), match='foo--bar'>

Remember from above that foo-*bar matched the string 'foobar' because the * metacharacter allows for zero occurrences of '-'. The + metacharacter, on the other hand, requires at least one occurrence of '-'. That means there isn’t a match on line 1 in this case.

?

Matches zero or one repetitions of the preceding regex.

Again, this is similar to * and +, but in this case there’s only a match if the preceding regex occurs once or not at all:

>>>

1>>> re.search('foo-?bar', 'foobar') # Zero dashes

2<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 6), match='foobar'>

3>>> re.search('foo-?bar', 'foo-bar') # One dash

4<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='foo-bar'>

5>>> print(re.search('foo-?bar', 'foo--bar')) # Two dashes

6None

In this example, there are matches on lines 1 and 3. But on line 5, where there are two '-' characters, the match fails.

Here are some more examples showing the use of all three quantifier metacharacters:

>>>

>>> re.match('foo[1-9]*bar', 'foobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 6), match='foobar'>

>>> re.match('foo[1-9]*bar', 'foo42bar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 8), match='foo42bar'>

>>> print(re.match('foo[1-9]+bar', 'foobar'))

None

>>> re.match('foo[1-9]+bar', 'foo42bar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 8), match='foo42bar'>

>>> re.match('foo[1-9]?bar', 'foobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 6), match='foobar'>

>>> print(re.match('foo[1-9]?bar', 'foo42bar'))

None

This time, the quantified regex is the character class [1-9] instead of the simple character '-'.

*?+???

The non-greedy (or lazy) versions of the

*,+, and?quantifiers.

When used alone, the quantifier metacharacters *, +, and ? are all greedy, meaning they produce the longest possible match. Consider this example:

>>>

>>> re.search('<.*>', '%<foo> <bar> <baz>%')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(1, 18), match='<foo> <bar> <baz>'>

The regex <.*> effectively means:

- A

'<'character - Then any sequence of characters

- Then a

'>'character

But which '>' character? There are three possibilities:

- The one just after

'foo' - The one just after

'bar' - The one just after

'baz'

Since the * metacharacter is greedy, it dictates the longest possible match, which includes everything up to and including the '>' character that follows 'baz'. You can see from the match object that this is the match produced.

If you want the shortest possible match instead, then use the non-greedy metacharacter sequence *?:

>>>

>>> re.search('<.*?>', '%<foo> <bar> <baz>%')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(1, 6), match='<foo>'>

In this case, the match ends with the '>' character following 'foo'.

There are lazy versions of the + and ? quantifiers as well:

>>>

1>>> re.search('<.+>', '%<foo> <bar> <baz>%')

2<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(1, 18), match='<foo> <bar> <baz>'>

3>>> re.search('<.+?>', '%<foo> <bar> <baz>%')

4<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(1, 6), match='<foo>'>

5

6>>> re.search('ba?', 'baaaa')

7<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 2), match='ba'>

8>>> re.search('ba??', 'baaaa')

9<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 1), match='b'>

The first two examples on lines 1 and 3 are similar to the examples shown above, only using + and +? instead of * and *?.

The last examples on lines 6 and 8 are a little different. In general, the ? metacharacter matches zero or one occurrences of the preceding regex. The greedy version, ?, matches one occurrence, so ba? matches 'b' followed by a single 'a'. The non-greedy version, ??, matches zero occurrences, so ba?? matches just 'b'.

{m}

Matches exactly

mrepetitions of the preceding regex.

This is similar to * or +, but it specifies exactly how many times the preceding regex must occur for a match to succeed:

>>>

>>> print(re.search('x-{3}x', 'x--x')) # Two dashes

None

>>> re.search('x-{3}x', 'x---x') # Three dashes

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 5), match='x---x'>

>>> print(re.search('x-{3}x', 'x----x')) # Four dashes

None

Here, x-{3}x matches 'x', followed by exactly three instances of the '-' character, followed by another 'x'. The match fails when there are fewer or more than three dashes between the 'x' characters.

{m,n}

Matches any number of repetitions of the preceding regex from

mton, inclusive.

In the following example, the quantified <regex> is -{2,4}. The match succeeds when there are two, three, or four dashes between the 'x' characters but fails otherwise:

>>>

>>> for i in range(1, 6):

... s = f"x{'-' * i}x"

... print(f'{i} {s:10}', re.search('x-{2,4}x', s))

...

1 x-x None

2 x--x <_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 4), match='x--x'>

3 x---x <_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 5), match='x---x'>

4 x----x <_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 6), match='x----x'>

5 x-----x None

Omitting m implies a lower bound of 0, and omitting n implies an unlimited upper bound:

| Regular Expression | Matches | Identical to |

|---|---|---|

<regex>{,n} |

Any number of repetitions of <regex> less than or equal to n |

<regex>{0,n} |

<regex>{m,} |

Any number of repetitions of <regex> greater than or equal to m |

---- |

<regex>{,} |

Any number of repetitions of <regex> |

<regex>{0,} <regex>* |

If you omit all of m, n, and the comma, then the curly braces no longer function as metacharacters. {} matches just the literal string '{}':

>>>

>>> re.search('x{}y', 'x{}y')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 4), match='x{}y'>

In fact, to have any special meaning, a sequence with curly braces must fit one of the following patterns in which m and n are nonnegative integers:

{m,n}{m,}{,n}{,}

Otherwise, it matches literally:

>>>

>>> re.search('x{foo}y', 'x{foo}y')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='x{foo}y'>

>>> re.search('x{a:b}y', 'x{a:b}y')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='x{a:b}y'>

>>> re.search('x{1,3,5}y', 'x{1,3,5}y')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 9), match='x{1,3,5}y'>

>>> re.search('x{foo,bar}y', 'x{foo,bar}y')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 11), match='x{foo,bar}y'>

Later in this tutorial, when you learn about the DEBUG flag, you’ll see how you can confirm this.

{m,n}?

The non-greedy (lazy) version of

{m,n}.

{m,n} will match as many characters as possible, and {m,n}? will match as few as possible:

>>>

>>> re.search('a{3,5}', 'aaaaaaaa')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 5), match='aaaaa'>

>>> re.search('a{3,5}?', 'aaaaaaaa')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 3), match='aaa'>

In this case, a{3,5} produces the longest possible match, so it matches five 'a' characters. a{3,5}? produces the shortest match, so it matches three.

Grouping Constructs and Backreferences

Grouping constructs break up a regex in Python into subexpressions or groups. This serves two purposes:

- Grouping: A group represents a single syntactic entity. Additional metacharacters apply to the entire group as a unit.

- Capturing: Some grouping constructs also capture the portion of the search string that matches the subexpression in the group. You can retrieve captured matches later through several different mechanisms.

Here’s a look at how grouping and capturing work.

(<regex>)

Defines a subexpression or group.

This is the most basic grouping construct. A regex in parentheses just matches the contents of the parentheses:

>>>

>>> re.search('(bar)', 'foo bar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

>>> re.search('bar', 'foo bar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

As a regex, (bar) matches the string 'bar', the same as the regex bar would without the parentheses.

Treating a Group as a Unit

A quantifier metacharacter that follows a group operates on the entire subexpression specified in the group as a single unit.

For instance, the following example matches one or more occurrences of the string 'bar':

>>>

>>> re.search('(bar)+', 'foo bar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 7), match='bar'>

>>> re.search('(bar)+', 'foo barbar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 10), match='barbar'>

>>> re.search('(bar)+', 'foo barbarbarbar baz')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(4, 16), match='barbarbarbar'>

Here’s a breakdown of the difference between the two regexes with and without grouping parentheses:

| Regex | Interpretation | Matches | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

bar+ |

The + metacharacter applies only to the character 'r'. |

'ba' followed by one or more occurrences of 'r' |

'bar''barr''barrr' |

(bar)+ |

The + metacharacter applies to the entire string 'bar'. |

One or more occurrences of 'bar' |

'bar''barbar''barbarbar' |

Now take a look at a more complicated example. The regex (ba[rz]){2,4}(qux)? matches 2 to 4 occurrences of either 'bar' or 'baz', optionally followed by 'qux':

>>>

>>> re.search('(ba[rz]){2,4}(qux)?', 'bazbarbazqux')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 12), match='bazbarbazqux'>

>>> re.search('(ba[rz]){2,4}(qux)?', 'barbar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 6), match='barbar'>

The following example shows that you can nest grouping parentheses:

>>>

>>> re.search('(foo(bar)?)+(ddd)?', 'foofoobar')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 9), match='foofoobar'>

>>> re.search('(foo(bar)?)+(ddd)?', 'foofoobar123')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 12), match='foofoobar123'>

>>> re.search('(foo(bar)?)+(ddd)?', 'foofoo123')

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 9), match='foofoo123'>

The regex (foo(bar)?)+(ddd)? is pretty elaborate, so let’s break it down into smaller pieces:

| Regex | Matches |

|---|---|

foo(bar)? |

'foo' optionally followed by 'bar' |

(foo(bar)?)+ |

One or more occurrences of the above |

ddd |

Three decimal digit characters |

(ddd)? |

Zero or one occurrences of the above |

String it all together and you get: at least one occurrence of 'foo' optionally followed by 'bar', all optionally followed by three decimal digit characters.

As you can see, you can construct very complicated regexes in Python using grouping parentheses.

Capturing Groups

Grouping isn’t the only useful purpose that grouping constructs serve. Most (but not quite all) grouping constructs also capture the part of the search string that matches the group. You can retrieve the captured portion or refer to it later in several different ways.

Remember the match object that re.search() returns? There are two methods defined for a match object that provide access to captured groups: .groups() and .group().

m.groups()

Returns a tuple containing all the captured groups from a regex match.

Consider this example:

>>>

>>> m = re.search('(w+),(w+),(w+)', 'foo,quux,baz')

>>> m

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 12), match='foo:quux:baz'>

Each of the three (w+) expressions matches a sequence of word characters. The full regex (w+),(w+),(w+) breaks the search string into three comma-separated tokens.

Because the (w+) expressions use grouping parentheses, the corresponding matching tokens are captured. To access the captured matches, you can use .groups(), which returns a tuple containing all the captured matches in order:

>>>

>>> m.groups()

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

Notice that the tuple contains the tokens but not the commas that appeared in the search string. That’s because the word characters that make up the tokens are inside the grouping parentheses but the commas aren’t. The commas that you see between the returned tokens are the standard delimiters used to separate values in a tuple.

m.group(<n>)

Returns a string containing the

<n>thcaptured match.

With one argument, .group() returns a single captured match. Note that the arguments are one-based, not zero-based. So, m.group(1) refers to the first captured match, m.group(2) to the second, and so on:

>>>

>>> m = re.search('(w+),(w+),(w+)', 'foo,quux,baz')

>>> m.groups()

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

>>> m.group(1)

'foo'

>>> m.group(2)

'quux'

>>> m.group(3)

'baz'

Since the numbering of captured matches is one-based, and there isn’t any group numbered zero, m.group(0) has a special meaning:

>>>

>>> m.group(0)

'foo,quux,baz'

>>> m.group()

'foo,quux,baz'

m.group(0) returns the entire match, and m.group() does the same.

m.group(<n1>, <n2>, ...)

Returns a tuple containing the specified captured matches.

With multiple arguments, .group() returns a tuple containing the specified captured matches in the given order:

>>>

>>> m.groups()

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

>>> m.group(2, 3)

('quux', 'baz')

>>> m.group(3, 2, 1)

('baz', 'quux', 'foo')

This is just convenient shorthand. You could create the tuple of matches yourself instead:

>>>

>>> m.group(3, 2, 1)

('baz', 'qux', 'foo')

>>> (m.group(3), m.group(2), m.group(1))

('baz', 'qux', 'foo')

The two statements shown are functionally equivalent.

Backreferences

You can match a previously captured group later within the same regex using a special metacharacter sequence called a backreference.

<n>

Matches the contents of a previously captured group.

Within a regex in Python, the sequence <n>, where <n> is an integer from 1 to 99, matches the contents of the <n>th captured group.

Here’s a regex that matches a word, followed by a comma, followed by the same word again:

>>>

1>>> regex = r'(w+),1'

2

3>>> m = re.search(regex, 'foo,foo')

4>>> m

5<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='foo,foo'>

6>>> m.group(1)

7'foo'

8

9>>> m = re.search(regex, 'qux,qux')

10>>> m

11<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='qux,qux'>

12>>> m.group(1)

13'qux'

14

15>>> m = re.search(regex, 'foo,qux')

16>>> print(m)

17None

In the first example, on line 3, (w+) matches the first instance of the string 'foo' and saves it as the first captured group. The comma matches literally. Then 1 is a backreference to the first captured group and matches 'foo' again. The second example, on line 9, is identical except that the (w+) matches 'qux' instead.

The last example, on line 15, doesn’t have a match because what comes before the comma isn’t the same as what comes after it, so the 1 backreference doesn’t match.

Numbered backreferences are one-based like the arguments to .group(). Only the first ninety-nine captured groups are accessible by backreference. The interpreter will regard 100 as the '@' character, whose octal value is 100.

Other Grouping Constructs

The (<regex>) metacharacter sequence shown above is the most straightforward way to perform grouping within a regex in Python. The next section introduces you to some enhanced grouping constructs that allow you to tweak when and how grouping occurs.

(?P<name><regex>)

Creates a named captured group.

This metacharacter sequence is similar to grouping parentheses in that it creates a group matching <regex> that is accessible through the match object or a subsequent backreference. The difference in this case is that you reference the matched group by its given symbolic <name> instead of by its number.

Earlier, you saw this example with three captured groups numbered 1, 2, and 3:

>>>

>>> m = re.search('(w+),(w+),(w+)', 'foo,quux,baz')

>>> m.groups()

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

>>> m.group(1, 2, 3)

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

The following effectively does the same thing except that the groups have the symbolic names w1, w2, and w3:

>>>

>>> m = re.search('(?P<w1>w+),(?P<w2>w+),(?P<w3>w+)', 'foo,quux,baz')

>>> m.groups()

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

You can refer to these captured groups by their symbolic names:

>>>

>>> m.group('w1')

'foo'

>>> m.group('w3')

'baz'

>>> m.group('w1', 'w2', 'w3')

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

You can still access groups with symbolic names by number if you wish:

>>>

>>> m = re.search('(?P<w1>w+),(?P<w2>w+),(?P<w3>w+)', 'foo,quux,baz')

>>> m.group('w1')

'foo'

>>> m.group(1)

'foo'

>>> m.group('w1', 'w2', 'w3')

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

>>> m.group(1, 2, 3)

('foo', 'quux', 'baz')

Any <name> specified with this construct must conform to the rules for a Python identifier, and each <name> can only appear once per regex.

(?P=<name>)

Matches the contents of a previously captured named group.

The (?P=<name>) metacharacter sequence is a backreference, similar to <n>, except that it refers to a named group rather than a numbered group.

Here again is the example from above, which uses a numbered backreference to match a word, followed by a comma, followed by the same word again:

>>>

>>> m = re.search(r'(w+),1', 'foo,foo')

>>> m

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='foo,foo'>

>>> m.group(1)

'foo'

The following code does the same thing using a named group and a backreference instead:

>>>

>>> m = re.search(r'(?P<word>w+),(?P=word)', 'foo,foo')

>>> m

<_sre.SRE_Match object; span=(0, 7), match='foo,foo'>

>>> m.group('word')

'foo'

(?P=<word>w+) matches 'foo' and saves it as a captured group named word. Again, the comma matches literally. Then (?P=word) is a backreference to the named capture and matches 'foo' again.

(?:<regex>)

Creates a non-capturing group.

(?:<regex>) is just like (<regex>) in that it matches the specified <regex>. But (?:<regex>) doesn’t capture the match for later retrieval:

>>>

>>> m = re.search('(w+),(?:w+),(w+)', 'foo,quux,baz')

>>> m.groups()

('foo', 'baz')

>>> m.group(1)

'foo'

>>> m.group(2)

'baz'

In this example, the middle word 'quux' sits inside non-capturing parentheses, so it’s missing from the tuple of captured groups. It isn’t retrievable from the match object, nor would it be referable by backreference.

Why would you want to define a group but not capture it?

Remember that the regex parser will treat the <regex> inside grouping parentheses as a single unit. You may have a situation where you need this grouping feature, but you don’t need to do anything with the value later, so you don’t really need to capture it. If you use non-capturing grouping, then the tuple of captured groups won’t be cluttered with values you don’t actually need to keep.

Additionally, it takes some time and memory to capture a group. If the code that performs the match executes many times and you don’t capture groups that you aren’t going to use later, then you may see a slight performance advantage.

(?(<n>)<yes-regex>|<no-regex>)(?(<name>)<yes-regex>|<no-regex>)

Specifies a conditional match.

A conditional match matches against one of two specified regexes depending on whether the given group exists:

-