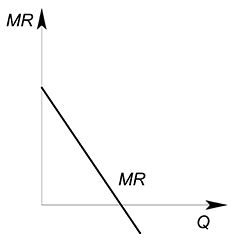

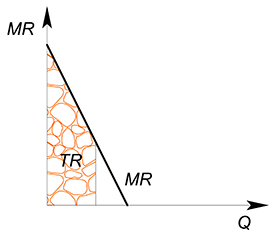

Типичный вид кривой предельного дохода.

Предельный доход (англ. marginal revenue – MR), также предельная выручка, — дополнительный доход, получаемый от производства дополнительной единицы продукции.

Предельный доход является показателем изменения дохода и формально высчитывается как производная функции дохода по объему производства:

Согласно микроэкономической теории, чтобы максимизировать прибыль, производители должны расширять или сокращать производство, пока предельный доход не сравняется с предельными издержками.

См. также[править | править код]

- Выручка

Предельная

выручка (MR

– marginalrevenue)

– это добавочный доход, приносимый

выпуском (продажей) дополнительной,

последней единицы продукции.

Она

рассчитывается следующим образом:

![]()

Важным

замечанием является то, что на рынке

совершенной конкуренции предельная

выручка фирмы всегда равна цене,

так как каждая единица продукции

реализуется по заданной цене:

MR=P

В

соответствии с предельным подходом,

фирма на каждом объеме выпуска Q

должна сравнить предельные издержки

MC

и предельную выручку MR,

и на основе этого соотношения найти

оптимальный объем выпуска Q*.

Запишем

возможные варианты этого соотношения

схематично:

1.MR

> MC

→ произ-во добавочной единицы прибыльно

(МП

– предельная прибыль > 0 → есть

стимулы

к расширению производства

2.MR

< MC

→ произ-во добавочной единицы убыточно

(МП<

0 → расширение производства невозможно

3.

MR = MC

→ условие

максимизации прибыли,

когда отсутствуют стимулы к расширению

произ-ва (МП

= 0) → оптимальный объем выпуска Q*

найден

Таким

образом, для рынка совершенной конкуренции

условием

максимизации прибыли

является соотношение MR

= MC = P

, так как предельная выручка признается

равной цене.

Отметим,

что не всегда можно подобрать такой

объем выпуска, при котором будет

наблюдаться именно равенство

между MR

и МС,

так как это является идеальным вариантом

для максимизации прибыли. В тех случаях,

когда не представляется возможным

достичь равенства, выбирают тот объем

выпуска, при котором разница между MR

и МС

будет минимальной

и обязательно положительной,

то есть:

![]()

![]()

![]() MR

MR

> MC и

MR

– MC → min

Использование

второго подхода позволяет не только

определить оптимальный объем выпуска,

но и определить величину максимально

возможной прибыли:

![]()

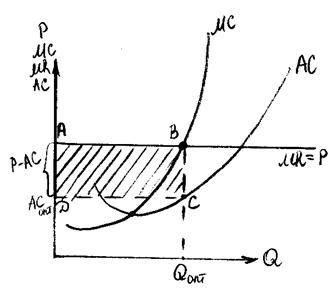

Графически

максимально возможная прибыль находится

следующим образом (рис. 42):

Рис.

42.

Максимизация прибыли на рынке совершенной

конкуренции

Оптимальный

объем выпуска соответствует точки

пересечения кривой MC

и линии MR.

Величина максимальной прибыли равна

площади прямоугольника ABCD.

3.

Минимизация убытков фирмой – совершенным

конкурентом

В

том случае, если цена становится ниже

минимальных средних издержек (Р<min

AC), то перед фирмой становится вопрос

не максимизации прибыли, а минимизации

убытков.

Минимальные

убытки находятся как разница между

общей выручкой TR и общими затратами TC:

L

= TR – TC

При

этом существует два

варианта

дальнейшего функционирования фирмы,

выбор которых зависит от того, где убытки

будут меньше:

1.

Временное закрытие производства. При

этом варианте объем выпуска равен нулю,

а, следовательно, и общая выручка равна

нулю. Что касается общих затрат ТС,

то они в условиях закрытия производства

будут равняться постоянным затратам

FC,

которые существуют даже при нулевом

объеме выпуска. Таким образом, возможные

убытки L

будут равны сумме постоянных затрат

FC.

Схематично

отобразим нахождение убытков по первому

варианту:

Q

= 0TR = 0TC = FCL = TR – TC = 0 – FC = – FC

2.

Продолжение убыточного производства.

Фирма решает продолжать убыточное

производство, получая выручку TR, которая

не может покрыть общие затраты TC,

состоящие из постоянных FC и переменных

затрат VC.

Постоянные

затраты существуют даже при нулевом

объеме выпуска, поэтому фирме надо

соизмерять общую выручку и переменные

затраты. Если переменные затраты окажутся

не столь велики, что даже останутся

средства из выручки на покрытие постоянных

затрат, то этот вариант будет

предпочтительней, чем первый:

Q

> 0TR > 0TC = FC + VC < 0L = TR – TC = TR – (FC + VC)TR

> VC → этот вариант предпочтительней,

чем первыйTR =

![]() ;То

;То

есть![]() P

P

> AVC

Таким

образом, ориентиром для принятия решения

закрывать производство или продолжать

убыточное (первый или второй вариант)

является соотношение цены и средних

переменных затрат:

1.

Если P

>min AVC,

то фирма принимает решение о продолжении

убыточного производства (второй вариант)

и выбирает тот объем выпуска, при котором

MR

= MC = P

– условием минимизации убытков (такое

же как и условие максимизации прибыли).

2

. Если

P <min AVC

, то фирма закрывает убыточное производство

(первый вариант), а следовательно

оптимальный объем выпуска равен нулю.

3

Если P

= min AVC,

то фирма должна принять решение о

закрытии производства. Точка пересечения

P и АС называется точкой

закрытия производства.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

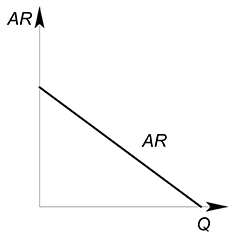

Linear marginal revenue (MR) and average revenue (AR) curves for a firm that is not in perfect competition

Marginal revenue (or marginal benefit) is a central concept in microeconomics that describes the additional total revenue generated by increasing product sales by 1 unit.[1][2][3][4][5]Marginal revenue is the increase in revenue from the sale of one additional unit of product, i.e., the revenue from the sale of the last unit of product. It can be positive or negative. Marginal revenue is an important concept in vendor analysis. [6][7]To derive the value of marginal revenue, it is required to examine the difference between the aggregate benefits a firm received from the quantity of a good and service produced last period and the current period with one extra unit increase in the rate of production.[8] Marginal revenue is a fundamental tool for economic decision making within a firm’s setting, together with marginal cost to be considered.[9]

In a perfectly competitive market, the incremental revenue generated by selling an additional unit of a good is equal to the price the firm is able to charge the buyer of the good.[3][10] This is because a firm in a competitive market will always get the same price for every unit it sells regardless of the number of units the firm sells since the firm’s sales can never impact the industry’s price.[1][3] Therefore, in a perfectly competitive market, firms set the price level equal to their marginal revenue

In imperfect competition, a monopoly firm is a large producer in the market and changes in its output levels impact market prices, determining the whole industry’s sales. Therefore, a monopoly firm lowers its price on all units sold in order to increase output (quantity) by 1 unit.[1][3][8] Since a reduction in price leads to a decline in revenue on each good sold by the firm, the marginal revenue generated is always lower than the price level charged

Profit maximization occurs at the point where marginal revenue (MR) equals marginal cost (MC). If

Definition[edit]

Marginal revenue is equal to the ratio of the change in revenue for some change in quantity sold to that change in quantity sold. This can be formulated as:[12]

This can also be represented as a derivative when the change in quantity sold becomes arbitrarily small. Define the revenue function to be[13]

where Q is output and P(Q) is the inverse demand function of customers. By the product rule, marginal revenue is then given by

where the prime sign indicates a derivative. For a firm facing perfect competition, price does not change with quantity sold (

Example 1: If a firm sells 20 units of books (quantity) for $50 each (price), this earns total revenue: P*Q = $50*20 = $1000

Then if the firm increases quantity sold to 21 units of books at $49 each, this earns total revenue: P*Q = $49*21 = $1029

Therefore, using the marginal revenue formula (MR)[12] =

Example 2: If a firm’s total revenue function is written as

Then, by first order derivation, marginal revenue would be expressed as

Therefore, if Q = 40,

MR = 200 − 2(40) = $120

Marginal revenue curve[edit]

Marginal revenue under perfect competition

Marginal revenue under monopoly

The marginal revenue curve is affected by the same factors as the demand curve – changes in income, changes in the prices of complements and substitutes, changes in populations, etc.[15] These factors can cause the MR curve to shift and rotate.[16] Marginal revenue curve differs under perfect competition and imperfect competition (monopoly).[17]

Under perfect competition, there are multiple firms present in the market. Changes in the supply level of a single firm does not have an impact on the total price in the market.[18] Firms follow the price determined by market equilibrium of supply and demand and are price takers.[19] The marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line at the market price, implying perfectly elastic demand and is equal to the demand curve.[20]

Under monopoly, one firm is a sole seller in the market with a differentiated product.[17] The supply level (output) and price is determined by the monopolist in order to maximise profits, making a monopolist a price maker.[21] The marginal revenue for a monopolist is the private gain of selling an additional unit of output. The marginal revenue curve is downward sloping and below the demand curve and the additional gain from increasing the quantity sold is lower than the chosen market price.[22][23] Under monopoly, the price of all units lowers each time a firm increases its output sold, this causes the firm to face a diminishing marginal revenue.[24]

Marginal revenue curve and marginal cost curve[edit]

A company will stop producing a product/service when marginal revenue (money the company earns from each additional sale) equals marginal cost (the cost the company costs to produce an additional unit). Therefore, a company is making money when MR is greater than marginal cost (MC). And when MC = MR, it is called profit maximization. After this point; the company can no longer make a profit. Therefore, it is in their interest to stop production.[25]

Relationship between marginal revenue and elasticity[edit]

The relationship between marginal revenue and the elasticity of demand by the firm’s customers can be derived as follows:[26][27][28]

- Taking the first order derivative of total revenue:

where R is total revenue, P(Q) is the inverse of the demand function, and e < 0 is the price elasticity of demand written as

Monopolist firm, as a price maker in the market, has the incentives to lower prices to boost quantities sold.[17] The price effects occur when a firm raises its products’ prices and increased revenue on each unit sold. The quantity effect, on the other hand, describes the stage when prices increased and consumers quantity demanded reduce. Firms’ pricing decision, therefore, is based on the tradeoff between the two outcomes by considering elasticity.[29]

When a monopolist firm is facing an Inelastic demand curve (e<1), it implies that a percentage change in quantity is less than the percentage change in price. By increasing quantity sold, the firm is forced to accept a reduction of price for all the current and previous production units,[23] resulting in a negative marginal revenue (MR). As such, as consumers are less sensitive and responsive to lower prices movement and so the expected product sales boost is highly unlikely and firms lose more profits due to reduction in marginal revenue. A rational firm will have to maintain its current price levels instead or increase the price for profit expansion.[27][30][31]

Increases in consumer’s responsiveness to small changes in prices leads represents an elastic demand curve (e>1), resulting in a positive marginal revenue (MR) under monopoly competition. This signifies that a percentage change in quantity outweighs the percentage change in price. Firms in the imperfect competition market that lower prices by a small portion benefit from a large percentage increase in quantity sold and this generates greater marginal revenue. With that, a rational firm will recognize the value of price effects under an elastic demand function for its products and would avoid increasing prices as the quantity (demand) lost would be amplified due to the elastic demand curve.[27][30][31]

If the firm is a perfect competitor, where quantity produced and sold has no effect on the market price, then the price elasticity of demand is negative infinity and marginal revenue simply equals the (market-determined) price

Therefore, it is essential to be aware of the elasticity of demand. A monopolist prefers to be on the more elastic end of the demand curve in order to gain a positive marginal revenue. This shows that a monopolist reduces output produced up to the point where marginal revenue is positive.[27][28]

Marginal revenue and Marginal benefit[edit]

Example 1: Suppose consumers want to buy an additional lipstick. If the consumer is willing to pay $ 50 for this extra lipstick, the marginal income of the purchase is $ 50. However, the more lipsticks consumers have, the less they pay for the next lipstick. This is because as consumers accumulate more and more lipsticks, the benefits of having an additional lipstick will be reduced.

Example 2: Suppose customers are considering buying 10 computers. If the marginal income of the 11th computer is $ 2, and the computer company is willing to sell the 11th component to maximize its consumer interest, the company’s marginal income is $ 2 and consumers’ marginal income is $ 2.

law of diminishing marginal returns[edit]

In microeconomics, for every unit of input added to a firm, the return received decreases.

When a variable factor of production is put into a firm at a constant level of technology, the initial increase in this factor of production will increase output, but when it exceeds a certain limit, the increased output will diminish and will eventually reduce output in absolute terms.[32]

law of increasing marginal returns[edit]

In contrast to the law of diminishing marginal returns, in a knowledge-dependent economy, as knowledge and technological inputs increase, the output increases and the producer’s returns tend to increase. This is an example of increasing marginal revenue; suppose a company produces toy airplanes. After some production, the company spends $10 in materials and labor to build the 1st toy airplane. The 1st toy airplane sells for $15, which means the profit on that toy is $5. Now, suppose that the 2nd toy airplane also costs $10, but this time it can be sold for $17. The profit on the 2nd toy airplane is $12 greater than the profit on the 1st toy airplane.

Marginal revenue and markup pricing[edit]

Profit maximization requires that a firm produces where marginal revenue equals marginal costs. Firm managers are unlikely to have complete information concerning their marginal revenue function or their marginal costs. However, the profit maximization conditions can be expressed in a “more easily applicable form”:

- MR = MC,

- MR = P(1 + 1/e),

- MC = P(1 + 1/e),

- MC = P + P/e,

- (P − MC)/ P = −1/e.[33]

Markup is the difference between price and marginal cost. The formula states that markup as a percentage of price equals the negative (and hence the absolute value) of the inverse of the elasticity of demand.[33] A lower elasticity of demand implies a higher markup at the profit maximising equilibrium.[31]

(P − MC)/ P = −1/e is called the Lerner index after economist Abba Lerner.[34] The Lerner index is a measure of market power — the ability of a firm to charge a price that exceeds marginal cost. The index varies from zero (when demand is infinitely elastic (a perfectly competitive market) to 1 (when demand has an elasticity of −1). The closer the index value is to 1, the greater is the difference between price and marginal cost. The Lerner index increases as demand becomes less elastic.[34]

Alternatively, the relationship can be expressed as:

- P = MC/(1 + 1/e).

Thus, for example, if e is −2 and MC is $5.00 then price is $10.00.

Example

If a company can sell 10 units at $20 each or 11 units at $19 each, then the marginal revenue from the eleventh unit is (11 × 19) − (10 × 20) = $9.

See also[edit]

- Cost curve

- Profit maximization

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d Bradley R. chiller, “Essentials of Economics”, New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1991.

- ^ Edwin Mansfield, “Micro-Economics Theory and Applications, 3rd Edition”, New York and London:W.W. Norton and Company, 1979.

- ^ a b c d e Roger LeRoy Miller, “Intermediate Microeconomics Theory Issues Applications, Third Edition”, New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc, 1982.

- ^ Tirole, Jean, “The Theory of Industrial Organization”, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1988.

- ^ John Black, “Oxford Dictionary of Economics”, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Primont, D. F., & Primont, D. (1995). Further Evidence of Positively Sloping Marginal Revenue. Southern Economic Journal, 62(2), 481–485. https://doi.org/10.2307/1060699

- ^ Wilson, T. (1979). The Price of Oil: A Case of Negative Marginal Revenue. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 27(4), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.2307/2097955

- ^ a b c d e f Schiller, Bradley R.; Gebhardt, Karen (2017). Essentials of economics (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN 978-1-259-23570-2. OCLC 955345952.

- ^ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2009). Principles of microeconomics (5th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-324-58998-6. OCLC 226358094.

- ^ O’Sullivan & Sheffrin (2003), p. 112.

- ^ Fisher, Timothy C. G.; Prentice, David; Waschik, Robert G. (2010). Managerial economics : a strategic approach. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 9780415495172. OCLC 432989728.

- ^ a b Pindyck, Robert S. (3 December 2014). Microeconomics. Rubinfeld, Daniel L. (Global edition, Eighth ed.). Boston [Massachusetts]. ISBN 978-1-292-08197-7. OCLC 908406121.

- ^ “3.2: Monopoly Profit-Maximizing Solution”. Social Sci LibreTexts. 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Goldstein, Larry Joel; Lay, David C.; Schneider, David I. (2004). Brief calculus & its applications (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-13-046618-2. OCLC 50235091.

- ^ Landsburg, Steven E. (2013). Price theory and applications (Ninth ed.). Stamford, CT. ISBN 978-1-285-42352-4. OCLC 891601555.

- ^ Landsburg, S Price 2002. p. 137.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Manoj (2015-05-08). “Revenue Curves under Different Markets (With Diagram)”. Economics Discussion. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ “The Supply Curve of a Competitive Firm”. saylordotorg.github.io. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ “Demand in a Perfectly Competitive Market”. www.cliffsnotes.com. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Russell W. Cooper; Alun Andrew John (2011). Microeconomics : theory through applications. Arlington, Virginia. ISBN 978-1-4533-1328-2. OCLC 953968136.

- ^ McLean, William J. (William Joseph) (2013). Economics and contemporary issues. Applegate, Michael. (9e ed.). Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-111-82339-9. OCLC 775406167.

- ^ Tuovila, Alicia. “Marginal Revenue (MR) Definition”. Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ a b “Marginal revenue for a monopolist”. www.economics.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ “The Monopoly Model”. saylordotorg.github.io. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ Boyce, Paul (February 6, 2021). “Marginal Revenue Definition”. Boycewire.

- ^ Perloff (2008) p. 364.

- ^ a b c d e f “3.3: Marginal Revenue and the Elasticity of Demand”. Social Sci LibreTexts. 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ a b Rekhi, Samia (2016-05-16). “Marginal Revenue and Price Elasticity of Demand”. Economics Discussion. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ Paul Krugman; Robin Wells; Iris Au; Jack Parkinson (2013). Microeconomics (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-4005-5. OCLC 796082268.

- ^ a b Pemberton, Malcolm; Rau, Nicholas (2011). Mathematics for economists : an introductory textbook (3rd ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8705-9. OCLC 756276243.

- ^ a b c d “Leibniz: The elasticity of demand”. www.core-econ.org. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ Bondarenko, Peter. “microeconomics”. Encyclopedia Britannica, Mar 25, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/microeconomics. Accessed 21 April 2023.

- ^ a b Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D (2001) p. 334.

- ^ a b Perloff (2008) p. 371.

References[edit]

- Landsburg, S 2002 Price Theory & Applications, 5th ed. South-Western.

- Perloff, J., 2008, Microeconomics: Theory & Applications with Calculus, Pearson. ISBN 9780321277947

- Pindyck, R & Rubinfeld, D 2001: Microeconomics 5th ed. Page Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-019673-8

- Samuelson & Marks, 2003 Managerial Economics 4th ed. Wiley

- O’Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.

Определение 1

Выручка (TR) – это доход (денежная сумма), который фирма получает от продажи по некоторой цене какого-то количества произведенной продукции:

$TR=Pcdot Q$

Функция выручки – зависимость между количеством производимого блага и величиной денежной суммы, получаемой от продажи товара. Функция выручки выводится из спроса:

$TR=P(Q)cdot Q$

Функции выручки могут иметь совершенно разнообразный вид:

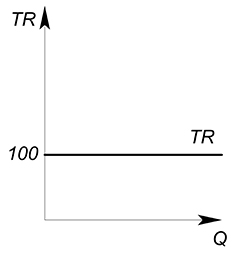

Пример 1

Функция спроса описывается зависимостью $Q(P)=dfrac{100}{P}$. Найти функцию выручки.

Выразим обратную функцию спроса: $P(Q)=dfrac{100}{Q}$; теперь найдем функцию выручки: $TR=dfrac{100}{Q} cdot Q=100$. В данном случае выручка постоянна, не зависит от количества производимого блага и равна 100.

Подробнее о функции выручки мы будем говорить, когда будем изучать рыночные структуры.

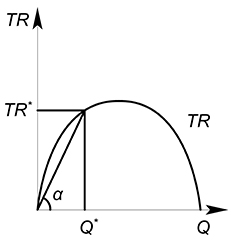

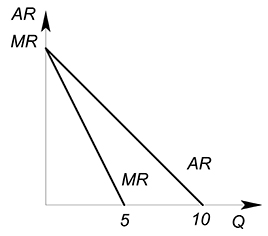

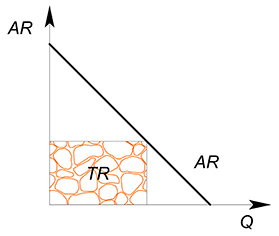

Определение 2

Средняя выручка (AR – average revenue) показывает, какую выручку в среднем приносит единица продаваемого товара:

$AR=dfrac{TR}{Q}$

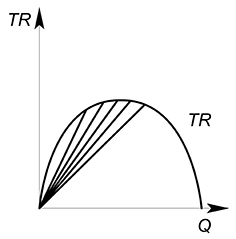

Геометрический смысл средней выручки – тангенс угла наклона луча (секущей), проведенного из начала координат к какой-нибудь точке на графике выручки:

$tg alpha = dfrac {TR^*}{Q^*}$

Проведя огромное количество лучей к графику выручки мы сможем получить график средней выручки $AR$.

Так среднюю выручку можно описать функцией, вид которой будет совпадать с обратной функцией спроса:

$AR=dfrac{TR(Q)}{Q}=P(Q)$

Определение 3

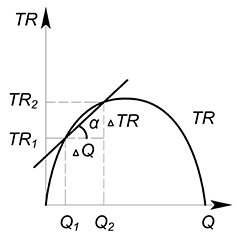

Определение 3

Предельная выручка (MR – marginal revenue) показывает, какую выручку принесет дополнительная произведенная единица товара.

В дискретном случае предельная выручка будет равна $MR=dfrac {TR_2-TR_1}{Q_2-Q_1}=dfrac{Delta TR}{Delta Q}$

Геометрический смысл предельной выручки – тангенс угла наклона секущей, соединяющей точки $(Q_2;TR_2)$ и $(Q_1;TR_1)$.

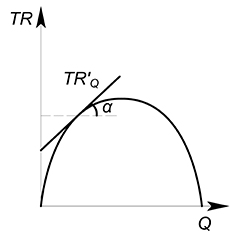

Если мы предполагаем, что производимый нами товар является бесконечно делимым, то нам будет интересно узнать какую выручку принесет дополнительная бесконечно малая единица выпускаемого блага.

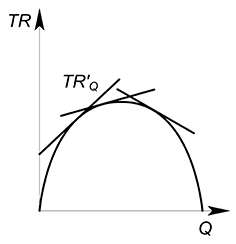

Тогда геометрический смысл в данном случае будет следующий: MR есть тангенс угла наклона касательной, проведенной к графику функции выручки в интересующей нас точке.

Проведя множество касательных к разным точкам сможем построить функцию предельной выручки:

В данном случае предельная выручка будет производной функции выручки: $MR(Q)=TR'(Q)$.

Пример 2

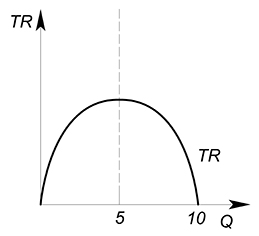

Функция спроса описывается уравнением $Q(P)=10-P$. Найти функции TR, AR, MR и изобразить их графики.

Выразим обратную функцию спроса: $P(Q)=10-Q$. Теперь найдем функцию выручки: $TR(Q)=P(Q)cdot Q=10Q-Q^2$. Можно найти функции средней и предельной выручки: $AR(Q)=dfrac {TR(Q)}{Q}=10-Q$, $MR(Q)=TR'(Q)=10-2Q$. Изобразим графики:

Максимизация функции выручки выполняется так же, как и любой другой функции – можно использовать производную (подробнее о максимизации функции можете узнать здесь), а можно обойтись без нее (подробнее здесь)

Максимизация функции выручки выполняется так же, как и любой другой функции – можно использовать производную (подробнее о максимизации функции можете узнать здесь), а можно обойтись без нее (подробнее здесь)

Пример 3

Обратная функция спроса имеет вид: $P(Q)=20-2Q$. Найти максимальную выручку.

Запишем функцию выручки: $TR=20Q-2Q^2$. Это парабола, ветви вниз. Найдем точку максимума: $x_0=-dfrac{b}{2a}=dfrac{20}{4}=5$. Подставим данную точку в функцию выручки: $TR=20cdot 5-2cdot 25=100-50=50$.

Также для функции $AR$ $TR$ в точке будет является произведением значений координат на осях:

для $MR$ – $TR$ в точке есть площадь под графиком функции, слева ограниченная осью $P$, справа перпендикуляром к оси $Q$, проведенным из интересующей нас точки:

Без дохода нет и дела. Это известно каждому. Однако, когда люди слышат о теоретических терминах, таких как предельный доход, то считают это чем-то ненужным для практического применения в бизнесе. Хотя на самом деле, именно эти величины позволяют быстро узнать реальные потенциальные возможности дела.

Но, обо всем по порядку

Виды дохода

Прежде всего, необходимо знать и разбираться в самих понятиях дохода, а так же как они рассчитываются. Советую так же почитать про разницу между выручкой, доходом и прибылью.

Общий доход

Общий доход (TR) – это вся сумма выручки, полученная в рамках реализации товаров или предоставления услуг. Формула следующая:

TR = P * Q

где P – это цена товара, а Q – это объем товара

Как видите, вычисляется очень просто. Однако, сразу отметьте себе, что общий доход зависит от цены товара и объема. То есть, их нужно совместно учитывать. Далее станет понятно, о чем именно идет речь.

Средний доход

Средний доход (AR) – это сколько выручки приходится на каждую единицу товара или же услуги. Формула следующая:

AR = TR / Q = P * Q / Q = P

где TR – это общий доход, P – это цена реализации, а Q – это объем товара

Хоть из формулы можно посчитать, что средний доход не нужно вычислять, а можно просто брать цену товара, это не совсем так. Дело в том, что в зависимости от изменения цен в разных временных интервалах или же при учете нескольких видов товаров, данная характеристика может отличаться.

Предельный доход

Предельный доход (MR) – это характеристика, отражающая какой прирост дохода будет происходить с каждой дополнительно выпущенной единицей товара или оказанной услуги. Формула следующая:

MR = (TRn – TRn-1) / (Qn – Qn-1)

В частном случае для 1 единицы товара все сводится к цене реализации.

Предельный доход позволяет оценить имеет ли смысл производить больше товара или же нет. Чтобы понять о чем идет речь, рассмотрим два примера.

1. Допустим стоимость товара составляет 10 рублей и вы производите 10 единиц товара. При увеличении объемов до 12 штук, доход возрастет на 20 рублей.

2. Та же самая ситуация, однако считаем, что увеличение товара приводит к тому, что цену необходимо снизить до 8 рублей. В таком случае, TR1 = 10 * 10 = 100 рублей, а TR2 = 8 * 12 = 96 рублей. Это значит, что MR = (96 – 100) / (12 – 10) = -2 рубля. То есть, увеличение объема приведет к снижению общей прибыли.

Может сложиться впечатление, что это весьма поверхностный анализ, однако предельный доход применяется в паре с предельными издержками. К этому и переходим.

Взаимосвязь дохода с предельными издержками

Чтобы понимать для чего может быть полезен предельный доход, стоит так же ознакомиться с тем, что представляют собой предельные издержки. Там так же рассмотрен частный случай взаимосвязи с ценами, при так называемой совершенной конкуренции (когда цена товара остается одинаковой при любых объемах).

В реальности же речь всегда идет о несовершенной конкуренции, при которой с увеличением объема товара необходимо снижать цену, так как спрос ограничен для каждого уровня цен. Выглядит это следующим образом:

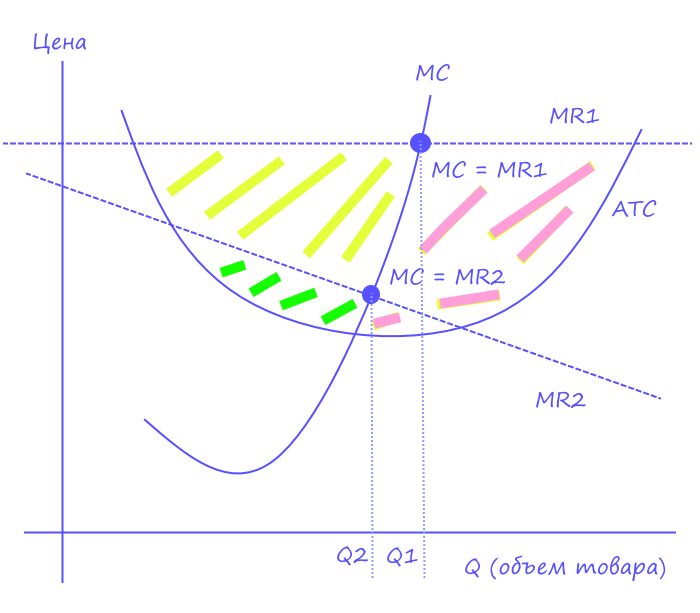

Здесь:

MR1 – это предельный доход для случая совершенной конкуренции, при которой цена товара остается одинаковой.

MR2 – это предельный доход для случая несовершенной конкуренции, при которой цена товара уменьшается с увеличением объемов.

ATC – это средние издержки на 1 добавленную единицу товара.

MC – это предельные издержки, отражающие изменение на 1 добавленную единицу товара.

Как уже ранее отмечалось, то для случая MR1 вся область, где возможна прибыль, ограничена ATC и MR1 (так как цена будет превышать издержки), то есть зеленая, желтая и фиолетовые зоны.

Однако, важно понимать, что начиная с определенного объема товаров, предельные издержки начнут превышать предельный доход. Это означает, что после точки, где их значения совпадают (точки Q1 и Q2), так называемое золотое правило MC = MR, реальная суммарная прибыль со всего оборота товаров начнет уменьшаться.

Поэтому при достижении этой точки считается, что дальнейший рост производства товаров или предоставления услуг не имеет экономической выгоды. Так что в практике реальными секторами с прибылью считаются зеленый для случая MR2 и зеленый с желтым для случая MR1.

Стоит отметить, что графический расчет не всегда удобен, поэтому нередко прибегают к представлению в виде таблицы, где для каждого объема товаров указываются все расчетные величины, а так же цена реализации. После чего просто смотрят, где наблюдается самая малая разница между предельными доходами и предельными издержками (с положительным знаком). Этот объем и считают максимально выгодным.

Послесловие

В рамках данной заметки, вы узнали что такое общий, средний и предельный доход, а так же как он взаимосвязан с предельными издержками и для чего предназначен.

Хотелось бы еще раз отметить, что, зная все расчетные величины, включая предельный доход и предельные издержки, можно весьма быстро понимать общую обстановку и, соответственно, принимать решения (например, увеличивать или уменьшать объемы, имеет ли смысл рассматривать иной подход к бизнесу, чтобы снизить планку издержек, и многое другое).

Похожие записи

-

ПАММ счет -

Паевые инвестиционные фонды (ПИФ) -

Что такое инвестиции? -

Эффект масштаба производства -

Что такое издержки? -

Что такое маржа? -

SMM – что это такое? -

Что такое активы и пассивы простыми словами?